A Reluctant Embrace: China’s New Relationship with the Taliban

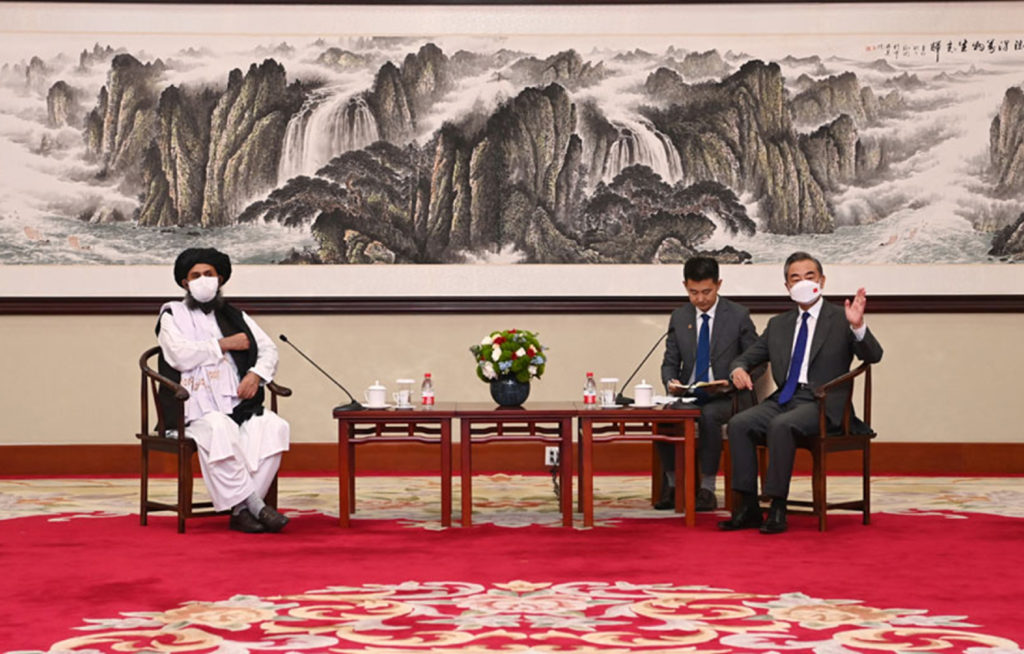

As the United States withdraws from Afghanistan and leaves a security vacuum there, is China moving in by cozying up to the Taliban? On July 28, Chinese State Councilor and Foreign Minister Wang Yi held a high-profile official meeting with a delegation of nine Afghan Taliban representatives, including the group’s co-founder and deputy leader Mullah Abdul Ghani Baradar. This was not the first visit by Taliban members to China, but the meeting was unprecedented in its publicity, the seniority of the Chinese attendees, and the political messages conveyed. Most notably, Wang used the meeting to publicly recognize the Taliban as a legitimate political force in Afghanistan, a step that has major significance for the country’s future development.

Even so, close examination of the meeting’s details and the Chinese government’s record of engagement with the Taliban reveals that the future path of the relationship is far from certain. Not only is the endgame of the armed conflict in Afghanistan undetermined. There are also questions about how moderate the Taliban will ever be, which has a tremendous impact on Chinese officials’ perception of, and policy toward, the organization. Additionally, despite the narrative that Afghanistan could play an important role in the Belt and Road Initiative as well as in regional economic integration, economics is not yet an incentive for China to lunge into the war-plagued country. China has been burned badly in its previous investments in Afghanistan and will tread carefully in the future. In an effort to further its political and economic interests, the Chinese government has reluctantly embraced the Taliban, but it has also hedged by continuing to engage diplomatically with the Afghan government.

China’s Public Recognition of the Taliban as a Legitimate Political Force

In 1993, four years after the Soviet Union had withdrawn its last troops from Afghanistan and one year after the Afghan communist regime had collapsed, China evacuated its embassy there amid the violent struggle then taking place. After the Taliban seized power in 1996, the Chinese government never established an official relationship with that regime. The Taliban’s fundamentalist nature, their association with and harboring of al-Qaeda, and their questionable relationship with Uighur militants all led Chinese officials to view them negatively.

Even as China has maintained its official recognition of the Afghan government, in recent years, Chinese officials have developed a relationship with the Taliban in response to the deteriorating security situation in Afghanistan and shifts in the balance of power on the ground. In 2015, China hosted secret talks between representatives of the Taliban and Afghan government in Urumqi, the capital city of the Xinjiang Uighur Autonomous Region. In July 2016, a Taliban delegation — led by Sher Mohammad Abbas Stanekzai, then the group’s senior representative in Qatar — visited Beijing. During the trip, the Taliban representatives reportedly sought China’s understanding and support for their positions in Afghan domestic politics. China’s engagement efforts intensified in 2019, as peace talks between the United States and the Taliban gained speed. In June of that year, Baradar, who had become head of the Taliban’s political office in Qatar and is viewed as a moderate figure by Chinese officials, visited China for official meetings on the Afghan peace process and counter-terrorism issues. After the negotiations between the Taliban and the United States in Doha faltered in September 2019, China tried to fill the void by inviting Baradar again to participate in a two-day, intra-Afghan conference in Beijing. It was originally scheduled for Oct. 29 and 30 of that year. It was postponed at least twice, in October and November, before China and ultimately the world plunged into the COVID-19 crisis. The meeting never took place.

China’s keen and active engagement with the Taliban reveals Beijing’s deepening perception of the group’s critical role in Afghanistan after the U.S. troop withdrawal. During his meeting with Baradar last month, Wang publicly described the Taliban as “a crucial military and political force in Afghanistan that is expected to play an important role in the peace, reconciliation, and reconstruction process of the country.” This was the first time that any Chinese official publicly recognized the Taliban as a legitimate political force in Afghanistan, a significant gesture that will boost the group’s domestic and international standing. As Chinese officials battle a reputation for cozying up to the Afghan Taliban — designated a terrorist organization by Canada, Russia, and others — it is important for them to justify the rationale for their engagement.

Wang did not forget to diss Washington in the meeting with the Taliban: He emphasized “the failed U.S. policy on Afghanistan” and encouraged the Afghan people to stabilize and develop their country without foreign interference. Although the United States was not the focus of the meeting, Chinese officials did draw a contrast between what they consider America’s selective approach to Afghan politics and China’s “benevolent” role by virtue of its self-proclaimed noninterference principle and amical approach to all political forces in Afghanistan.

The third aspect of Wang’s message focused on the demand that the Taliban “sever all ties with all terrorist organizations, including the East Turkestan Islamic Movement,” a Muslim separatist group founded by militant Uighurs. Although many have questioned the existence of the organization, and the Trump administration removed it from the U.S. Terrorist Exclusion List last November, the presence of Uighur militants in Afghanistan and their political aspirations are real. This issue has been a priority for Chinese officials in their dealings with all political forces in Afghanistan. In fact, without the Taliban’s public promise in July not to harbor any group hostile to China, it is questionable whether Chinese officials would have issued such a high-profile recognition of the Taliban as a legitimate political force at all.

China’s Balancing Diplomacy

While the Taliban delegation’s recent visit to Beijing has garnered much publicity, less attention was paid to what happened just prior to it. Twelve days before, General Secretary Xi Jinping had a phone conversation with Afghan President Ashraf Ghani. Xi emphasized “China’s firm support of the Afghan government to maintain the nation’s sovereignty, independence, and territorial integrity.” The call highlighted that not only does China still recognize Ghani’s government as the legitimate representative of Afghanistan, but that Beijing also has pledged its support to Ghani in relation to the peace process and much-needed COVID-19 relief, at least for the time being.

There are different views in China over the likely outcome of the conflict between the Taliban and the Afghan government. Although many analysts assess that the Taliban will eventually prevail, some prominent Chinese experts have argued that the group’s victory is “only one of the possibilities” and that its territorial advances have been exaggerated. Even if many signs point to potential victory by the Taliban, the nature and timing of that event remain to be seen. For the Chinese government, uncertainty about the future of Afghan politics underscores the need for a balanced approach that maintains ties with both sides, as perfectly illustrated by Xi’s phone call with Ghani and Wang’s meeting with the Taliban.

As long as the civil war in Afghanistan persists, the Chinese government will continue to pursue this diplomatic balancing act as the best way to promote its interests. Indeed, China needs both the Afghan government and the Taliban to help protect the security of Chinese assets and nationals on the ground, as well as to combat organizations such as the East Turkestan Islamic Movement. In the event the Taliban and Afghan government end up in a prolonged stalemate, China also desires to play the role of a mediator — even if outsiders see it more as a facilitator — which requires China not to pick a side.

A China-Taliban Romance?

The meeting between Wang and the Taliban delegation was not all cozy. And China’s budding relationship with the group comes with conditions. Wang told his visitors — in a style reminiscent of a lecture — that they need to “build a positive image and pursue an inclusive policy.” The implied message is that if the Taliban enact draconian measures again, this will inevitably affect China’s stance toward them. Indeed, some Chinese experts have called for the Taliban to make more changes in their policies in order to modernize and pursue a moderate direction. The Taliban’s ability and willingness to do so will determine the depth and breadth of China’s future engagement with them.

Chinese officials have felt a growing need to curry favor with the Taliban as the security situation in Afghanistan and the surrounding region has deteriorated. On June 19, the Chinese Foreign Ministry issued a rare warning calling for all Chinese nationals and entities in Afghanistan to “evacuate as soon as possible” in anticipation of intensified fighting in the country. Two days after the Wang-Taliban meeting, the Foreign Ministry issued the same warning once again. In neighboring Pakistan, three high-profile attacks against Chinese nationals have been launched in the last four months: the April 22 bombing of a hotel in Quetta where the Chinese ambassador was staying, a bus explosion in Kohistan that killed nine Chinese engineers in mid-July, and the shooting in Karachi of a car carrying Chinese engineers on the same day the Taliban delegation met with Wang. The Pakistani Taliban claimed responsibility for the Quetta attack and analysts also suspected that it is culpable in the other attacks. Some Chinese experts have warned that the security vacuum created by the U.S. withdrawal from Afghanistan could lead to an intensification of violence against Chinese nationals in the region. Hence, Chinese officials will likely see a need to rely on the Afghan Taliban not to target China, as well as to help influence or rein in those who might.

The relationship is born of necessity rather than preference. Many Chinese officials and analysts have doubts about how modernized the Afghan Taliban will ever be. Although some in China assess that the Taliban have become more pragmatic, there is no guarantee for what their policy will look like, especially regarding relations with radical Islamic organizations in the region. In addition, even if the core of the Taliban adopts a neutral, or even friendly, policy toward China, whether it could rein in all of the group’s radical factions remains a major question. Chinese officials don’t see many choices other than working with the Afghan Taliban, but the relationship will be complex, and its course will be determined by numerous factors in the months and years ahead.

Economics Not Yet an Incentive

The Taliban have openly welcomed Chinese investment in the reconstruction of Afghanistan and have indicated they would guarantee the safety of investors and workers from China. However, China is unlikely to lunge into Afghanistan with major investment in the foreseeable future. There has consistently been a disconnect between Chinese rhetoric regarding Afghanistan’s economic potential and the actual scale of Chinese commercial projects in the country. In 2019, the Chinese ambassador to Afghanistan emphasized the important role Afghanistan could play in China’s Belt and Road Initiative as well as in Chinese-Pakistani-Afghan regional economic integration. Nevertheless, that rosy picture is not supported by the actual data. For the first six months of 2021, total Chinese foreign direct investment in Afghanistan was only $2.4 million, and the value of new service contracts signed was merely $130,000. That suggests that the number of Chinese companies and workers in Afghanistan is declining significantly. For the whole of 2020, total Chinese foreign direct investment in Afghanistan was $4.4 million, less than 3 percent of that type of Chinese investment in Pakistan, which was $110 million for the same year.

China has been burned badly in its investments in Afghanistan. Its two major projects to date — the Amu Darya basin oil project by China’s largest state-owned oil company, China National Petroleum Corporation, and the Aynak copper mine by state-owned China Metallurgical Group Corporation and the Jiangxi Copper Company Limited — have both been ill fated. The challenges have included archeological excavation that halted the progress of the Aynak copper mine, security threats, and renegotiation of terms as well as the challenges of resettling local residents. Among these, political instability and security threats have been the top concerns. As long as the security environment remains unstable, China is unlikely to launch major economic projects in Afghanistan. The American troop presence there was not the factor hindering Chinese economic activities. In fact, Chinese companies had benefited from the stability that U.S. troops provided. Therefore, the U.S. withdrawal is unlikely to encourage major Chinese investment.

Walking a Tightrope

In anticipation of prolonged conflict in Afghanistan, Beijing is trying to strike a balance in its diplomacy toward the Afghan government and the Taliban. Chinese officials’ recent recognition of the Taliban as a legitimate political force is significant. However, the prospects for that relationship remain uncertain as the Taliban’s future policies are unclear. China has the capacity to play a bigger role in the country economically, but a willingness to do so will only emerge when there are signs of sustainable stability. China has been weaving a net of bilateral, trilateral (China, Pakistan, and Afghanistan), and multilateral engagements to encourage that stability. If stability does not emerge in the foreseeable future, China most likely will avoid deep economic involvement in Afghanistan and will work with both the Afghan government and the Taliban to protect its interests on the ground.

Yun Sun is the director of the China program at the Stimson Center.