Iran’s Tricky Balancing Act in Afghanistan

Editor’s Note: Some links in this article lead to Iranian media sites. If access to such sites is prohibited by your employer’s policy, please do not click links in this article from a work computer.

A senior Iranian military leader, Esmail Qaani, traveled in late June to the Syrian border town of Albu Kamal to rally a group of fighters. Normally, this type of visit would not be unusual. Qaani commands the Quds Force — the wing of Iran’s Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps responsible for external action — and is expected to travel to Syria to coordinate Iran’s efforts to preserve the regime of Bashar al Assad. What made Qaani’s trip noteworthy was that he was visiting the Fatemiyoun Division, an Iran-backed proxy force whose foot soldiers are Afghans from the Shiite Hazara community.

While fighters of the Fatemiyoun Division remain active in Syria, so far they have been sidelined in Afghanistan. That could change. The Fatemiyoun constitute a small but potent force with longstanding and extensive ties to Iran and could prove useful to Iranian officials as they craft their Afghan policy, especially if the Taliban continue to press their military advantage. On July 7, Iran’s political leaders hosted talks between Taliban and Afghan government representatives in Tehran. While Iranian Foreign Minister Javad Zarif used the meeting to celebrate the U.S. departure from Afghanistan, he also warned that continuing clashes between Taliban fighters and the Afghan government would be costly. With the American military exit from Afghanistan due to be completed by Aug. 31, Iranian policymakers are strategizing about their future approach toward Afghanistan. They face a difficult set of decisions, including how they will balance their country’s strong ties to Afghanistan’s minority Hazara community against Iran’s diplomatic dance with the Taliban and the Afghan government.

The Fatemiyoun pale in comparison to the Taliban both in numbers and capacity. But they could prove either to be a lever of influence for Iran, if the Taliban and Afghan government do ultimately cut a deal, or a political liability, if an all-out civil war ensues in Afghanistan and the Taliban continue to target the country’s Shiite Hazara community.

There is significant risk of blowback for Iran if Afghanistan’s conflict takes on an even more sectarian cast with Afghan Hazara Shiites pitted against the predominantly Pashtun Sunni Taliban. If the history of the Afghan conflicts is any guide, such a scenario could draw in Iran’s regional rivals, the United Arab Emirates and Saudi Arabia, who would be likely to support the Taliban, as they have in the past. Plus, the United States has already demonstrated, with recent retaliatory airstrikes against Iran-backed proxies in Syria and Iraq, that it is prepared to use any means necessary to check threats to American interests in the region. Going forward, Iranian officials will likely feel a need to tread carefully with both the Fatemiyoun and the Taliban.

The Rise of the Fatemiyoun Division

As we explain in a recent report, the links between Iran’s revolutionary guard and Afghan and Pakistani Hazaras have their roots in the Iran-Iraq War. After Saddam Hussein’s Iraq invaded Iran in September 1980, Iran’s revolutionary government cast the war as an opportunity for Shiites to demonstrate their faith. Many Afghan Shiites answered the call by heading to Iran, where they were trained by the revolutionary guard.

During the 1980s, Iran’s effort to stand up an Afghan paramilitary force underwent several phases, name changes, and reorganizations. As well as training Shiite fighters in Iran, the guard also dispatched several of its officers to serve as cultural and military advisers in Afghanistan, where they embedded with cells in the resistance movement that was fighting the Soviet Union’s occupation of that country.

Following the Soviet withdrawal, conflict in Afghanistan raged on as various factions fought for power. Throughout the 1990s, Iran provided support to Afghan Shiite groups and the Northern Alliance in their fight against the Taliban. Qassem Soleimani was among the revolutionary guard personnel involved in that effort. He would become the head of the Quds Force in 1998 and remained its commander until he was killed in a U.S. drone strike last year.

From these deep and longstanding links to Afghanistan’s Shiite Hazara community, in 2012 Iran established the Fatemiyoun Division as part of its wide-ranging effort to support Syria’s Assad regime in its fight against an armed rebellion. Under the supervision and direction of Soleimani, the revolutionary guard recruited today’s Afghan Hazara foreign fighters for that purpose. It also established the Fatemiyoun’s Pakistani sister unit, the Zeynabiyoun Brigade. Thousands of ethnic Afghan and Pakistani Hazara foreign fighters fought and died with those units to help save the Assad regime.

In addition to their battlefield impact, the Fatemiyoun have been a significant propaganda asset for the revolutionary guard, which works to persuade constituents in the Shiite community across the region to support the Iranian government and its policies. Touting the daring and successes of Afghan foreign fighters in Syria has played an integral part in that campaign. Iran-financed propaganda about the Fatemiyoun employs strategic narratives related to differences in Sunni and Shiite interpretations of Islamic law and just governance, and it stokes fears among the Hazara about the potency of the predominantly Sunni Taliban and Islamic State forces in Afghanistan and Syria.

Soleimani was the key architect and star of Iran’s propaganda strategy. He made a habit of snapping frontline selfies with the Fatemiyoun and recounting their heroics. The Fatemiyoun achieved a substantial social media following on YouTube and Twitter until both platforms took down their accounts. Even so, the Fatemiyoun remain active on other social media as a result of Iran’s investment. They have thousands of followers on encrypted social media platforms such as Telegram and its Iranian government-controlled counterpart, Soroush, which they use to showcase their battlefield exploits in Syria. Fighters shared videos of combat on social media, which proved to be an effective recruiting tool — among those who joined the cause were a significant number of American-trained former soldiers in the Afghan National Army and elite Afghan special operations forces.

The revolutionary guard’s propaganda about the Fatemiyoun could have long-lasting ramifications. The guard corps has pushed sectarian narratives that may prove difficult to control in the future, notably including in relation to Afghanistan. In strengthening the Fatemiyoun, the revolutionary guard has given power to a network that, while deeply indebted to Iran, is not fully under its control. For Iran, managing risks in Afghanistan, where the Fatemiyoun are an important political force, could prove difficult over time if the Taliban continue their aggressive and bloody campaign of targeting Hazara communities. In that event, Iranian officials may be tempted to provide significant support to Fatemiyoun fighters to help Iran maintain its influence over the Hazara community and combat the Taliban.

The Future of the Fatemiyoun and Iran’s Approach Toward Afghanistan

Even as the Afghan and Pakistani Shiite militias’ involvement in Syria winds down, their power, and the narratives through which Iran framed their mobilization, will continue to shape South Asia and the Middle East for years to come. This is especially true in Afghanistan, where Iran’s strategic hedging and years-long quiet campaign to cultivate influence with the Taliban has contributed significantly to the military gains made by the insurgents over the last several years.

It remains to be seen if Iranian officials are able to sustain relations with both their Fatemiyoun proxies and the Taliban after the exit of their common enemy, the United States. Questions abound about whether and when Iran’s newly elected president, Ebrahim Raisi, might leverage Iranian influence over tens of thousands of Hazaras in Afghanistan and across South Asia who answered Tehran’s call to join the fight in Syria almost a decade ago. For Raisi, who has vowed to make Iran’s economic revival a centerpiece of his tenure, steering political outcomes in Afghanistan, which is one of Iran’s largest trading partners, is a crucial part of his own political calculus.

There are increasing concerns that the Taliban’s victories on the ground may translate into the revival of the harsh and bloody targeting of Afghan Shiite Hazaras, which could trigger unwelcome regional instability and have pronounced effects on Iran’s ailing economy. Iranian officials and media outlets close to the revolutionary guard have argued that the Taliban have changed. Whether that is true or not, Iran’s approach to dealing with the predominantly Pashtun Taliban will likely continue on Raisi’s watch in the near term. Playing all three major sides — pro-Taliban Pashtuns, ethnic Hazara Shiites, and Afghan elites affiliated with the government in Kabul — will likely be critical to Tehran’s approach in Afghanistan no matter what Washington does next.

The mixed signals coming out of Tehran on engagement in Afghan affairs may be both a sign of Iran’s pragmatism and a reflection of a deeper divide between hard-liners aligned with the supreme leader and reform-minded Iranian critics of Ali Khamenei’s regime. Disagreements between various camps on Iran’s engagement in Afghanistan have openly erupted in the Iranian press. In a recent column that appeared in Iran’s centrist online daily Arman, for instance, former Iranian diplomat Seyed Ali Khorram sharply criticized Khamenei’s engagement with the Taliban, saying it only emboldens the Taliban to continue their aggressive attacks against Afghan Shiite Hazaras. Khorram echoed the complaints of other Iranian reformists and reminded readers that Taliban attacks on Iranian diplomats during the 1990s brought Afghanistan and Iran to the brink of war.

Given that Iran has long positioned itself as the champion and protector of Afghanistan’s marginalized Shiite Hazara population, the internal rifts emerging over Iran’s cultivation of the Taliban suggest that Tehran’s diplomatic dalliances with the group may result only in a temporary marriage of convenience that could easily disintegrate after the U.S. drawdown is completed this summer. For now, how Iranian officials play their cards in Afghanistan is a game of wait and see.

Candace Rondeaux directs the Future Frontlines program at New America and is a professor at the Center on the Future of War at Arizona State University. She has covered the Afghan conflict for 13 years, working variously for the Washington Post, the International Crisis Group, and the U.S. Special Inspector General for Afghanistan Reconstruction.

Amir Toumaj is a nonresident fellow at New America and is the co-founder of the Resistance Axis Monitor.

Arif Ammar is an independent researcher based in Washington and a native of Kabul. He has produced analysis on the Afghan conflict for the International Crisis Group and the Armed Conflict Location and Event Database.

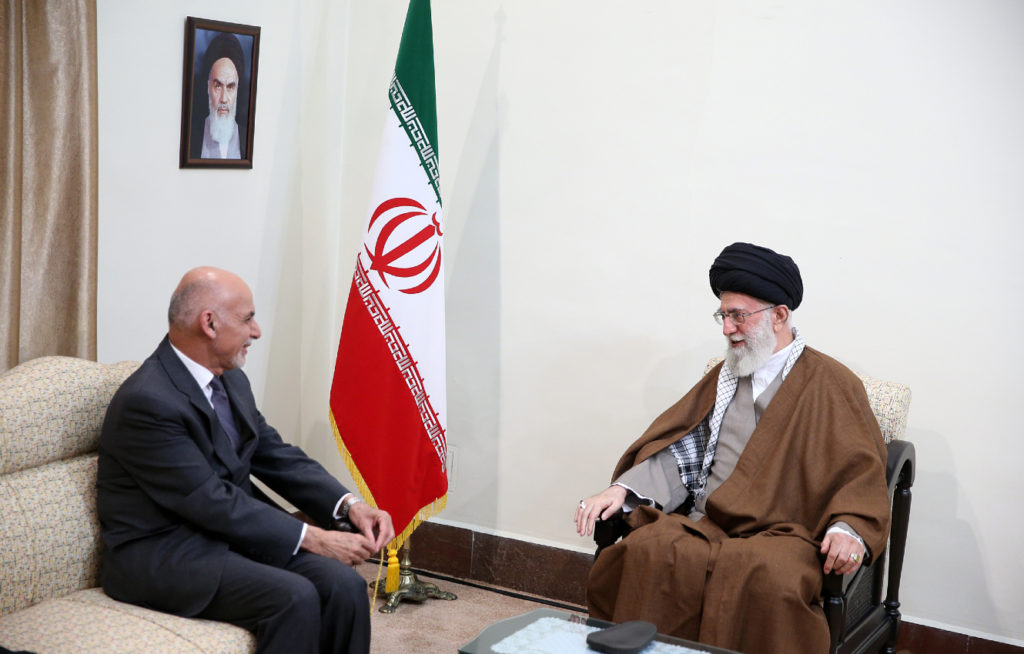

Image: Office of the Supreme Leader