Education Against Extremism: Suggestions for a Smarter Stand-Down

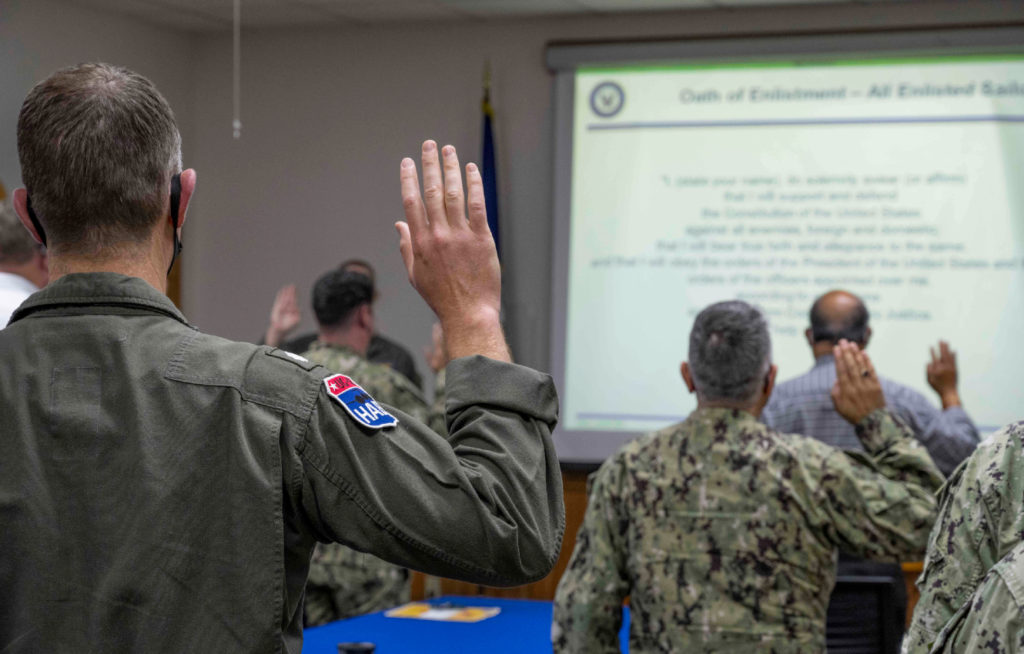

A large number of veterans, and even some active-duty officers, were among those who stormed the Capitol during the Jan. 6 insurrection. In response, the military leadership held small-group stand-down sessions across the force last spring to discuss the presence of extremism in the ranks and how best to eradicate it.

Yet, recent remarks from some officers tasked with implementing these sessions have raised concerns about their effectiveness and the uniformity with which they were executed. Worse, some participants described the stand-down day as “insufficient” while others wrote an open letter claiming that the event actually “undermine[d] trust.” Indeed, rather than serve as a productive moment for reflection and problem-solving, the stand-down instead appeared to be mired in the malaise that has plagued other “awareness days” focused on persistent problems such as suicide, post-traumatic stress disorder, and sexual assault.

Based on what we have observed in years of experience in multiple professional military education institutions, part of the problem stems from the lack of seriousness and preparation surrounding these sessions. To give extremism in the ranks the attention that it deserves, it should be folded into the regular curriculum. At the Army War College, we have tried to address this by implementing several structural reforms that better equip our faculty members to lead discussions about sensitive personnel issues. While there remains a long way to go, we argue that by approaching these topics from a civil-military relations perspective, bolstered by expert panels and prepared readings, we will better prepare our students for their future as senior leaders.

Senior-leader education cannot treat these stand-down days as just another training and checkbox exercise. We should instead critically engage the wealth of knowledge that exists around right-wing extremism in the military and use this as an opportunity to brainstorm ways in which senior officers can change culture in the absence of regulation. We should develop a framework that can address personnel issues in a thoughtful and rigorous way whenever they come up — and devote the kind of resources and care toward these issues that we do with every other lesson in the curriculum.

A Problematic Approach

The problems surrounding this spring’s extremism stand-down are not unique. As faculty members in professional military education, we have witnessed years of events known as “stand-downs,” “wingman days,” “awareness days,” and other training events intended to address the personnel issues that are currently plaguing the force. Yet these all suffer from a similar neglect — not the fault of any particular instructor, commander, or leader, but rather the result of everyone being overtasked and under-resourced when trying to accomplish educational objectives.

Two issues in particular regularly emerge. The first is the lack of institutional care that accompanies these sessions. They are rarely announced to the student body ahead of time, and even more rarely accompanied by a preview of what is to be discussed. As a result, students enter discussions unprepared and without proper time to reflect and self-assess. Sessions are held ad hoc and often done offsite, away from classroom materials and other resources that would communicate importance and encourage thoughtful, rigorous discussion. The institution rarely if ever spends money to bring in outside expertise, preferring to task lectures to students and faculty even though they are rarely experts on the topic. And despite the prevalence of student surveys on almost every aspect of the curriculum from core courses to advising, no student or faculty survey is conducted to evaluate the institution’s performance on these days. No follow-up sessions are announced, and discussions about potential solutions are rarely actually passed up to higher leadership. All of this builds to a general sentiment that stand-downs are unappreciated “add-on” days, rather than important parts of the professional military education experience.

Second, we lack a common framework for addressing the problems that we are tasked to tackle. Faculty preparation, if done at all, is largely limited strictly to a single department or select group of uniformed personnel. While most lessons in the core curriculum are accompanied by a corresponding faculty workshop, where lesson planners run through their intent for the session and offer their expertise and experience of teaching, instructors are instead sent into these small-group sessions largely blind — resulting in an unstructured discussion informed by nothing but individual experience, speculation, and emotional response. This is particularly problematic when dealing with issues like race and extremism. If a white commander has never had personal experience of confronting cases of white-power extremism, it becomes nearly impossible to run a discussion that relies on personal experience to generate debate and discussion. The result is a series of meandering conversations based primarily around the experiences of one or two people, uninformed by history, data, or potential solutions.

This dismissive approach to stand-down days is problematic for a number of reasons. First, it is bad for civil-military relations. Stand-down days are unique because they are ordered from the top down: They are one of the few times a year when we are explicitly tasked to address a particular issue that is on the secretary of defense’s mind. When the institutional response, however, is to simply treat these days as a “checkbox” exercise, it sends a signal to students and faculty alike that the secretary’s guidance can be effectively ignored. Over the last two months, Secretary Lloyd Austin not only ordered the entire force, both civilian and uniformed, to dedicate an entire day to addressing extremism in the ranks — a combined total of over 22 million man-hours — but he himself made a video addressing the force and had the service chiefs do the same. When professional military education institutions approach this with less preparation and attention than they do a lesson on ideology in World War II, they are in fact engaging in a form of soft shirking that undermines civilian control.

Second, not taking these days more seriously alienates those who participate. By consistently under-valuing and under-preparing for stand-down days, we risk alienating those members of the force who are being asked to share difficult stories and contribute their experiences to discussion. “Difficult conversations” about race, sexual assault, and suicide are emotionally taxing on minority groups, who are often asked to perform diversity, equity, and inclusion work without additional benefits or pay. When they take the leap of faith to contribute, only to discover that the day has been put together in an ad hoc manner, it further signals that the institution does not care about their experience. Indeed, some sexual assault survivors report that sexual assault and harassment awareness events only end up re-traumatizing them because of the careless way in which the sessions are handled. Similarly, conversations about extremism and race can be counter-productive when minorities are asked to share their personal encounters with extremist behavior without the proper institutional support. We need people with these experiences to be vulnerable and trust leadership to be sensitive to their concerns — and the nature of trust means that we only get so many bites at the apple.

Finally, it is problematic for the education of our senior military officers. The students who we educate in professional military education go on to lead at the highest levels of the military. They are the ones who will be responsible for setting personnel policy in the future, and those responsible for designing and implementing future stand-down days. Combating issues like domestic extremism in the ranks will be just as much a part of their job description as planning the next global campaign — yet we devote precious little time or energy to preparing students for doing so. The result is a senior leadership corps that continues to be tone-deaf in its response to personnel problems. From the now well-publicized “escape room” theater to discuss Sexual Harassment Assault Response Prevention (more popularly known as SHARP) reporting requirements to teal pancakes for sexual assault awareness, leaders routinely fail to treat these issues as the opportunities that they are to check in on the force.

What Professional Military Education Can Do

Professional military education has a unique role to play in changing the military’s response to extremism. As the United States, and thus the military’s recruiting pool, diversifies, senior officers will find themselves leading a force that increasingly looks very different from them — at least until minority retention issues are solved within the officer corps as well. These officers will need to know how to build trust in politically divisive times without simply relying on hackneyed tropes like “we all bleed green.” They will continue having to address personnel issues involving extremism, sexual assault, suicide, and religion. Just in the last year, we have seen the force deal with the murder of Spc. Vanessa Guillen and the Fort Hood report, the death of George Floyd, and subsequent revelations about discrimination in the Air Force, not to mention the participation of multiple active-duty military members in the Jan. 6 insurrection. When professional military education denies its students the opportunity to thoroughly discuss and debate these problems in an informed way, we do a disservice to the force that reverberates for a generation.

Yet it does not have to be this way. Indeed, professional military education already has a tried-and-true method for tackling controversial, important issues — through the education and lessons that it already offers to students. Rather than treat stand-down days as one-off exercises and “training sessions,” military educators should instead fold these topics into the broader curriculum and teach them as they would other elements of leadership and strategy. This includes assigning readings selected by in-house specialists, outlining learning objectives, and offering suggested discussion questions that can spark and shape conversation in productive ways. Professional military education should survey its students after the lesson to identify ways to improve and engage outside experts to help to supplement readings and discussions. In sum, stand-down days should be given the same kind of institutional attention and credit that the rest of the curriculum merits.

At the Army War College, we have recently made significant changes in our approach to diversity, equity, and inclusion and sexual assault awareness, though there remains a long way to go. Last year, we changed how Sexual Harassment Assault Response Prevention training was delivered to make it seminar-based, led by prepared faculty instructors supported by lesson materials and readings explicitly crafted for a senior-leader audience. We created three “Let’s Talk” sessions for discussion and engagement with diversity, equity, and inclusion efforts in the Army, and added a specific lesson on diversity in our Strategic Leadership course. An elective on “inclusive leadership” was added to the curriculum, which was met with high interest from our students and was subsequently well-subscribed.

For the stand-down, the Army War College convened a panel of experts to discuss the problems associated with extremism in the force and then broke into seminars facilitated by prepared faculty members. Next year, we will integrate personnel issues more fully into the curriculum, embedding discussion on the three harmful behaviors (sexual assault/harassment, extremism/racism, and suicide) into our core Strategic Leadership Course, and encouraging student research on combatting them that will filter up to the chief of staff of the Army.

Yet these changes, while welcome, are both recent and reversible. Without sessions that established buy-in from the entire faculty, seminar-based discussions last year varied considerably in their effectiveness. Using additional days to deliver content means that they are easily removed during an already busy year. And electives offer programming to students already interested in the topic — arguably those who need additional education the least — and can be cancelled. Institutionalizing these efforts will therefore require sustained commitment from curriculum developers and unqualified support from leadership, lest they turn into temporary anomalies. Yet they also provide a blueprint for how other professional military education institutions could approach integrating personnel issues into student education. All in all, we should leverage our expertise to create a lesson plan and curriculum for our students that adequately prepares them for the problems they will face in a rapidly changing organization.

Make the Content Compelling

Substance is also important. What follows are a series of suggestions for how we might best conduct discussions about extremism and other personnel issues going forward.

First, name the issue. The veterans who stormed the Capitol on Jan. 6 were members of groups that advocated for the violent disruption of government processes, as well as for white power and other extremist ideologies. Department of Defense Instruction 1325.06 explicitly defines extremist organizations as those that “advocate supremacist, extremist, or criminal gang doctrine, ideology or causes; including those that attempt to create illegal discrimination based on race, creed, color, sex, religion, ethnicity, or national origin; advocate the use of force, violence, or criminal activity; or otherwise engage in efforts to deprive individuals of their civil rights.” This definition is important, but it only takes us so far. More specific guidance from leadership would be invaluable, but in its absence faculty can foster a productive conversation dedicated to defining the problem. Indeed, until we begin with a common understanding of what extremist behaviors we are concerned about, discussion will stagnate around unhelpful questions like “what does extremism mean to you?” Tackling it up front helps to move the discussion forward and gives everyone a common definition and language to use.

Second, discuss the historic scope of the problem. In a working paper they presented at the 2021 Air University Diversity and Military Effectiveness Workshop, Jacqueline Whitt and Amber Batura argued that the military often tells itself a series of myths around social issues that erase the degree to which the force continues to grapple with discrimination and extremism. These myths tend to be along the lines of “While the military was initially opposed to the integration of a minority group, once the decision was made we all saluted and incorporated them, and now we are color blind.” This misperception bleeds into all group discussions about diversity, inclusion, and extremism in professional military education, and it will continue to until we take a closer look at history.

The U.S. military has a well-documented record of tolerating and even fostering extremist behavior — Kathleen Belew traces it in Bringing the War Home, William Taylor outlines it in his social history of military service, and a series of authors including Nora Bensahel, David Barno, and Simone Askew have examined it in War on the Rocks. This history is important because solutions to problems change based on how institutionally entrenched they are. If we treat topics like extremism as exceptions — thus ignoring the long history of discriminatory and violent behavior that has plagued the force for decades — we set our students up to develop short-term solutions that will ultimately do little to address deeper cultural issues. Understanding the strategic context, therefore, is a critical first step to thinking about topics like extremism in the ranks.

Third, get buy-in from the small group — both during faculty development and in seminar. Discuss why it is important that the force and future senior leaders pay attention to extremism in the ranks. Senior leadership has acknowledged repeatedly that there is a need for these discussions to serve as starting points, rather than ends in themselves. But in order to promote continuing conversations, our students should themselves become stakeholders in the process. And while there is truth to the secretary’s statement that “we must retain the trust of the American people,” this concept is too nebulous for even the brightest students to hold onto through multiple rounds of uncomfortable and oftentimes raw discussions with their subordinates. We therefore have students walk through four concrete and distinct ways that extremism in the force can compromise military effectiveness and civil-military relations more generally. When this problem is tackled from a civil-military relations perspective, students do not have to be experts in extremism per se in order to directly relate to the consequences of these attitudes on their soldiers and across the force.

In order to get buy in, we start at the lowest level of effect: unit trust and cohesion. When one member of the force is suspected or known to be a believer in white supremacist ideology, it undermines trust across the unit. The military has been granted significant authority over individuals’ lives in the name of establishing trust inside the unit. Offenses that are considered personal problems in civilian society, like adultery, are instead criminalized by the Uniform Code of Military Justice because of the need for trust, cohesion, and faith in one’s unit members. What effect does a commander who regularly ignores extremist rhetoric have on trust inside a diverse unit? When leaders tolerate bad behavior, that affects culture. And when trust declines, so does the organization’s ability to cope and adapt in the face of adversity, thereby reducing resiliency.

We then move on to the strategic level. Extremist ideology, and particularly the white-power movement, advocates for the superiority of certain types of people. Such hubris is incompatible with perspective-taking, a practice necessary to understanding the politics, strategic dispositions, and military cultures of globally dispersed allies, adversaries, and competitors. Of course, the denigration — whether in extremist or milder forms — of others’ cultures, ethnicities, and sociopolitical belief systems is also ethically problematic for a country and a military that espouses the moral worth and dignity of every person. In his latest book, H. R. McMaster calls for “strategic empathy” — the ability to put oneself in the shoes of one’s enemy and understand the interests that they are pursuing. This necessarily requires a level of respect and awareness that is largely missing from those who espouse extremist ideologies and white power. Just as attitudes about racial superiority contributed to strategic blunders by Germany, Japan, and even the United States leading up to and during World War II, the United States risks underestimating the intelligence, interests, and strategic acumen of its adversaries when extremists are in positions of power. Today, the United States already struggles to incorporate cultural experts into intelligence assessments and planning due to security protocols — a problem that has long been identified as a barrier to good assessment. What’s more, research suggests that diverse groups are less prone to group think, and that women-led teams tend to be more collaborative by nature. When the U.S. military sits quietly by while extremists create hostile environments for women and minorities, we do significant damage to our capacity for strategic assessment and ultimately contribute to diminished battlefield performance.

Next, we look at the impact on the force as a whole, particularly with regard to recruiting and retention. It is well known that there is a leaky pipeline amongst women and minorities in the service. Some of that has to do with the concentration of women and minorities in non-combat specialties, both by explicit policy and by preference. But culture also plays a significant role in deterring women and minorities from joining certain communities and chasing many out when they do. The Fort Hood report released last year explicitly stated that the toxic climate that led to Guillen’s murder “is not attributable to any one commander or command staff. Nor did it spontaneously combust during the review period or as a direct consequence of recent events. It was a culture that … developed over time and out of neglect over a series of commands that predated 2018. A toxic culture was allowed to harden and set.” If the military is seen by its members to tolerate racial discrimination and extremist ideologies, minorities will continue to flee the military at higher rates than whites, negatively impacting retention and further separating the military from the rest of American society.

This then also affects recruiting. As the United States edges ever closer to becoming a minority-majority country, the military will necessarily have to increase its recruiting amongst minority groups. Already the composition of enlisted forces is seeing significant demographic change, with black Americans slightly overrepresented and Hispanic Americans now only slightly underrepresented as a share of society. Yet the officer corps, and especially senior ranks, remain overwhelmingly white — creating new challenges for officers tasked with leading a force that looks increasingly different from them. A military that is seen to be sympathetic to extremist ideology, particularly white-power ideologies, alienates the very people it depends on to maintain the health of the force.

Finally, we discuss the broader issue of how society interacts with the military. What are the implications of a military that does not look like the society it is tasked to protect? Research increasingly shows that the military sees itself as better than American society. This perception risks exacerbating what many have called a “soft praetorianism” amongst the force — damaging democratic health and civilian control.

Moving Forward

It is only after we have laid this groundwork that we can begin to have a conversation about how to combat extremism in the force. Future leaders should first appreciate the history behind, and importance of, the problem before brainstorming ways to combat it.

These discussions do not necessarily have to remain at the war college level, though senior-leader development is the natural place for strategic-level conversations about diversity in the force. Personnel issues that spark these mandated “awareness days” affect units of all kinds. Every professional military education institution has departments dedicated to the study of leadership and specialists on civil-military relations. These faculty members can help to produce thoughtful and engaging material that can generate informed discussion on personnel topics. And education at every level of the force should communicate why solving problems about extremism, sexual assault, and racism are important to the health of the military — giving these missions a sense of purpose and solidarity.

Finally, we should resist the temptation to sideline discussing these issues because they have been politicized by elected officials. The stand-down, and content associated with it, have led to a series of accusations by Congressional Republicans that the U.S. military is attempting to enforce “woke” policies, thereby bringing the “culture war” to the Department of Defense. Some have even gone so far as to encourage active-duty members to report on their fellow servicemembers, while others have targeted professors and courses at the U.S. Military Academy and across military education. This contentious debate culminated in Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Mark Milley tersely telling members of the House Armed Services Committee that he found their accusations “personally … offensive.” This, in turn, prompted some conservative commentators to mock and insult Milley himself.

We are at precarious moment in American history, one where the country is actively negotiating whether right-wing violent extremism is to be tolerated in mainstream politics. But the Department of Defense definition of extremism remains clear in its rejection of supremacist ideology and the use of violence to achieve domestic political objectives. The military should remain committed to upholding this definition and empowering its own leaders and servicemembers in to foster an environment of unity, teamwork, and cohesion. And this requires fostering a serious, comprehensive, and informed discussion about extremism.

Carrie A Lee is the chair of the Department of National Security and Strategy at the U.S. Army War College and fellow with the Truman National Security Project. You can follow her on Twitter at @CarrieALee1.

Celestino Perez is an associate professor in the Department of National Security and Strategy, director of the Carlisle Scholars Program, and Douglas MacArthur Chair of Research at the U.S. Army War College.

Opinions expressed in this piece are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Army War College, U.S. Army, or Department of Defense.

Image: U.S. Navy (Photo by Mass Communication Spc. 1st Class David R. Krigbaum)

CORRECTION: The article has been updated to note that the Army War College created three “Let’s Talk” sessions for discussion and engagement with diversity, equity, and inclusion efforts in the Army. A previous version said that it had set aside three “skills days.” The article was also updated to clarify that the authors base their observations on years of experience in professional military education institutions, not solely their current positions at the U.S. Army War College.