The Budget (and Fleet) That Might Have Been

When the U.S. military was engaged in multiple ground wars in Asia, advocating for a larger ground force didn’t seem like a parochial idea. But, somehow, as defense officials shift their focus to competition with China in a theater that is dominated by water, some Army officers see advocating for more ships as the height of Navy parochialism. Some have responded to that imagined slight with ahistorical claims that “war is won, and peace is preserved, on land.” But the Indo-Pacific is a maritime theater. It is not parochialism to acknowledge that fact and adjust defense budgets to address that reality. Today’s Navy does not have the ships required to execute the U.S. national strategy in a time of relative peace and security, let alone in a future defined by competition and the threat of great-power war. The Biden administration’s Fiscal Year 2022 defense budget was an opportunity to arrest the Navy’s decline and recapitalize the fleet to address this uncertain future. Instead, its authors elected to perpetuate a status quo that would see the fleet continue to wither, while the competition surges ahead.

The U.S. National Defense Strategy clearly names the People’s Republic of China as America’s primary strategic competitor, while the secretary of defense made clear that China is, and will remain, America’s “pacing challenge.” That challenge is playing out on the world’s oceans, and it is likely to intensify. Yet, the president’s FY2022 defense budget proposal calls for funding procurement for only eight new ships, half of which are combat vessels, and plans to decommission 15. At that rate, should Congress elect not to find space in the budget to sustain, procure, and build more ships, the U.S. Navy’s battle force will not only fail to grow to 355 but will continue to shrink. By contrast, China tripled its navy battle force in under two decades and is projected to reach 400 ships by 2030. Recently, I suggested that the Army’s budget offers the most logical, least risky source for funding the needed increase in shipbuilding. Using the recently released Defense Futures Simulator to show my math, I am ready to double down on that recommendation, and defend the strategic logic behind cutting Army garrison strength.

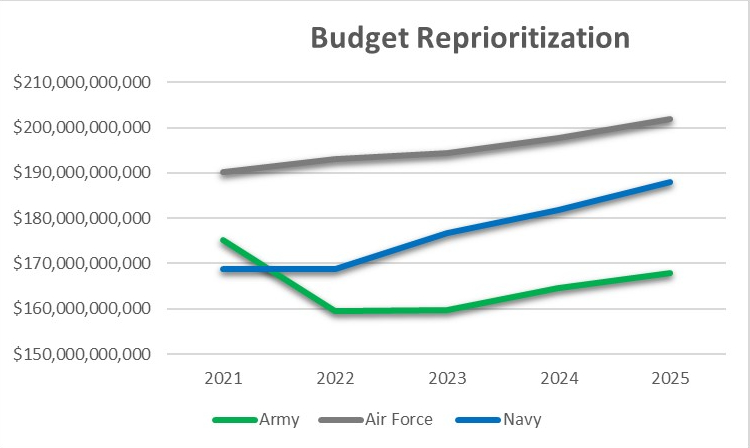

For a 7 percent decrease in active-duty Army garrison strength, the Navy could purchase 40 new ships over the current procurement plan and extend the service lives of 10 guided missile cruisers. Reprioritizing the budget this way would also enable the Navy to increase its readiness funding by roughly $700 million dollars each year from 2021 to 2025. This plan would keep the fleet above 300 ships, rather than sinking beneath that number within the next few years. This proposal is not a comprehensive restructuring of the entire budget. It is intended to highlight the need for a significant redistribution of defense spending from land-focused efforts to the maritime domain. In fact, the only cut made anywhere outside the Army budget in my proposal is to retire the U.S. Air Force’s A-10 fleet. This redistribution of funds within the Department of Defense assumes a static budget top line and generates a savings of $210 million over the course of five years.

Figures 1 & 2

Source: Generated by the author.

How to Win Without Fighting: Deterring Chinese Aggression

One concern voiced with cutting Army garrison strength is the idea that it makes it more difficult to deter China. But the size of the U.S. Army is not a deterrent to China. It is the height of arrogance to assume that decision-makers within the Chinese Communist Party are basing their foreign policy decisions upon estimates of U.S. ground force garrison strength when their domestic population is 1.4 billion and their ground force alone dwarfs the entire American military.

The U.S. Army has tens of thousands of troops based in Japan and South Korea. This is reflective of the basing realities in the Indo-Pacific. Put plainly, there are few other places for the Army to deploy in large numbers even in the event of conflict with China. Even stronger U.S. partners such as Thailand and the Philippines are not interested in large-scale deployments of ground forces. Several key factors limit the utility of ground forces in relation to China. First and foremost, China is a capable nuclear power with a credible second-strike capability in its modern ballistic missile submarines. The idea that the U.S. might launch a ground invasion on any Chinese-held territory seems heedless of escalation risks. Second, unless Chinese forces were deployed against a neighboring state, there is zero appetite among U.S. partners for cooperating with the U.S. Army against China, either in combined operations or by providing basing support. Finally, the U.S. Army will be almost entirely reliant on the maritime domain for its mobility and logistics in the Indo-Pacific in any conflict scenario. The U.S. Navy today is not ready nor equipped to meet those requirements, and the lead time required to recapitalize its fleet is measured in decades. The Army, by virtue of its composition, has more flexibility in this respect. It can draw upon large manpower reserves in the National Guard and Army Reserve and, in times of dire need, the draft to fill its ranks. The Navy cannot surge shipbuilding to fill operational gaps. It cannot draft a squadron of modern guided missile destroyers. A decision to recapitalize the fleet on the day it is needed will result in a failure to perform. The Army force rebalance proposed here still leaves an active-duty force larger than what the U.S. Navy, or any other present maritime capability within the Department of Defense, will have the capacity to transport forward in the event of a war against a peer.

The Army-Navy Game (Chinese and American Editions)

The U.S. national security community should recognize that the reorganization and modernization of the Chinese military saw 300,000 troops retrenched from the People’s Liberation Army in recent years. Meanwhile, an unequaled naval construction campaign propelled the People’s Liberation Army Navy past the U.S. Navy in the number of battle force ships in its fleet. Global Chinese investment focuses on controlling maritime infrastructure, with even key European ports falling under Chinese control. Aside from a limited base in Djibouti, though, there is no significant Chinese army presence anywhere in the world. In light of this, where might a half-million U.S. Army troops plan to confront Chinese forces? If Russia is driving projections, then a U.S. Army drawdown should also include coordination with NATO allies who would need to shoulder increased responsibility in their own backyard.

My notional budget sends three active armored brigade combat teams to the National Guard, along with two Stryker brigade combat teams, three infantry brigade combat teams, one Army aviation brigade, and one security force assistance brigade. That is approximately 38,200 soldiers from a force of approximately 485,000. It is not insignificant, but it is also not a permanent loss since those soldiers are still accessible upon recall from the National Guard. Each active-duty brigade combat team costs nearly three times the amount required to maintain the same capability in the National Guard. For a maritime nation like the United States, a standing army of half a million is strategic luxury American taxpayers can ill-afford. There are no threats on the American periphery. The protective barrier of two oceans affords space and time in keeping potential foreign challengers at arm’s length. The constitutional charge for Congress to “raise an army” but “provide and maintain a navy” still rings true. The modern United States’ global interests do require a standing army, but maintaining nearly 500,000 soldiers in garrison under peacetime conditions and present fiscal constraints is budgetary suicide. Regarding Congress’ constitutional duty to maintain a Navy, it is a simple fact that building ships takes far longer than training soldiers. This is why my budget proposes shifting resources from the Army to the Navy. I do not propose that the total force be permanently diminished but rather that slightly less than 10 percent of the garrison strength be moved to a reduced readiness status. The ground force combined end strength will remain over 1 million.

While some Army officers might see this move as a threat, it also frees up resources to address urgent needs within the Army. The shift in resources creates budget space for multiple years of accelerated funding for Army modernization priorities like the optionally manned fighting vehicle, future attack and reconnaissance aircraft, future long-range assault aircraft (V-280), and the Army’s long-range hypersonic strike program. Maintaining a garrison force of nearly a half million soldiers while undertaking a force-wide modernization effort simply will not be feasible in an era of static, or possibly shrinking, Department of Defense budget top lines. National security leadership should decide if they want a large army, or a modernized one, because that is the consequential decision before them. I propose a modernized force.

Reducing garrison strength also funds five years of increased funding for Army readiness, offering the opportunity to recapitalize on the heels of two protracted wars in the Middle East. The Army has borne the lion’s share of twenty years of non-stop deployments and combat operations, and it is time to rest, refit, and repair in order to meet the challenges the National Defense Strategy lays out. The money to do this — and to invest in the maritime resources required to fight in a maritime theater — can be found by shifting resources as I propose.

Understanding Timelines and Second-Order Effects

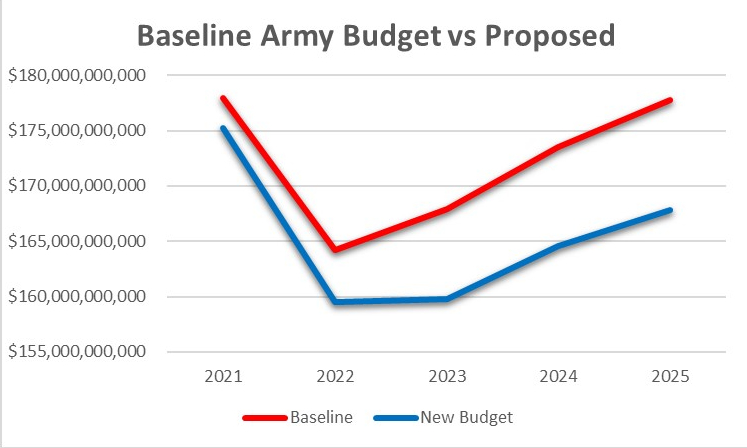

Figure 3

Source: Generated by the author.

My proposal presents a trade-off in immediately available landpower in exchange for concentrated effort at recapitalizing the U.S. Navy’s combat and logistics fleets. It limits U.S. options abroad, but that is not a bad thing. Past U.S. aspirations of maintaining a force capable of fighting two wars simultaneously were likely unrealistic even then, and it is time for the American national security community to abandon what is now effectively a fantasy. A ground force attempting to maintain sufficient readiness for wars with China, Russia, North Korea, and the nebulous threat of counter-insurgency will not be able to modernize without immense changes in national budget priorities that are unlikely to be forthcoming. Maintaining strategic focus on conventional deterrence vis-à-vis the People’s Republic of China will require trimming commitments and extraneous requirements. The era of doing more with less should end, as should the Pollyannaish hope that tomorrow will bring the bounteous budgets of yesteryear — doing less with less should become the watchword.

For those unfamiliar with the timelines involved in modern shipbuilding, perhaps one of the most instructive lessons that can be taken from the Defense Futures Simulator is that it is almost impossible to significantly increase the number of U.S. Navy ships between 2021 and 2025, no matter how much money is repurposed. Only by extending the service lives of existing ships and immediately increasing funding to the T-ATS Navajo-class salvage ships can the fleet be maintained above the threshold of 300 ships over the five-year period. This budget proposal should also come with the caveat that U.S. shipbuilding infrastructure is presently inadequate to achieve the ambitious targets set out, but there is hope yet that ambitious plans to revamp American infrastructure will address this key shortfall. Capitalism, however, might also alleviate some of this concern — as orders for ships increase,

shipbuilders will invest more in their own production capabilities to meet demand.

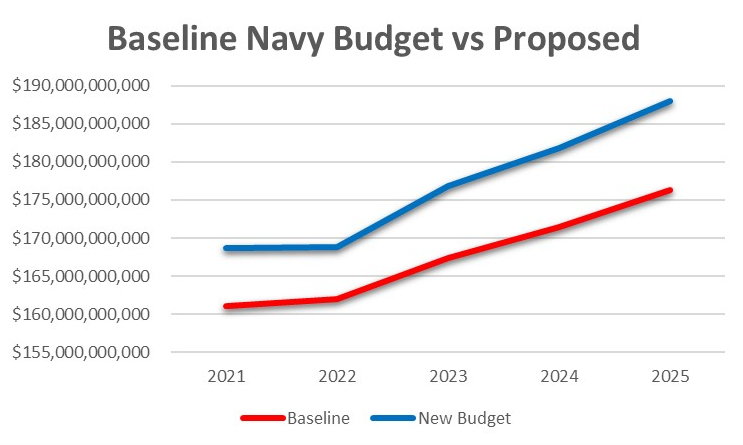

Figure 4

Source: Generated by the author.

With a meaningful redistribution of the budget, the Navy could increase its yearly purchase of San Antonio-class amphibious transport docks (LPD Flight II) by one ship per year. It would fund the purchase of 14 new Constellation-class frigates rather than the 5 currently planned. The Virginia-class nuclear attack submarine procurement would increase from nine planned hulls to 14. As mentioned, funding an extra five T-ATS Navajo-class salvage and rescue ships would see ships being launched before the end of the five-year period and would add to a critically neglected sector of the fleet. (Unappreciated in peacetime, capable salvage and rescue vessels become a critical capability in conflict.) An additional five John Lewis-class fleet oilers would reinforce the logistics fleet. The U.S. Navy’s nuclear-powered aircraft carriers are the only U.S. surface vessels that can operate without taking on fuel and even they require resupply for things like jet fuel, ordnance, and food stores to support their operations. (Nuclear-powered submarines similarly do not need to refuel.) If deterrence fails and war at sea occurs, U.S. fleet oilers will be an immediate target for any adversary, and the modern fleet lacks the depth to absorb any significant loss.

This budget reallocation also supports funding for an additional 11 unmanned surface vehicles, which represents the Navy’s vision for a future fleet incorporating unmanned ships alongside, or even independent from, crewed platforms. Without requirements for manning or stores, these vessels would contribute to the Navy’s distributed lethality concept at a far lower cost than traditional platforms.

Finally, this budget could increase Navy readiness funding by about $700 million per year. The Navy’s readiness shortfalls continue to generate headlines and studies following the deadly, high-profile collisions involving two destroyers in 2017 and fleet-wide maintenance, training, and readiness issues revealed in the subsequent investigations. The U.S. Government Accountability Office has documented the Navy’s efforts to address these issues but notes that the Navy is so deep in the so-called “readiness hole” that extricating itself will take years, even with focused effort. An increase of $700 million is unlikely to be sufficient, but it is still an increase and one that is affordable within the existing top line. Realistically, readiness will also depend on other aspects outside the scope of the tool. Things like shipyard availability, the size of the United States’ highly-skilled maritime workforce, and operational tempos all impact the Navy’s ability to provide a ready force.

A Shift in Focus Requires a Shift in Budget

The defense budget has been too conservative in its prescriptions since the cessation of major combat operations in Iraq and Afghanistan. While the budget is not divided into exact thirds, its partition into roughly similar shares has seen no major changes, no real prioritization, and calcification of the status quo in a dynamic period of global change. The U.S. Navy is a rusted, emaciated shadow of its former self and will not recover without urgent attention. It is time to reallocate the budget in a way that provides for necessary modernization for all services and recapitalizes the naval forces most likely to be in close contact with the United States’ pacing threat. The options available via the Defense Futures Simulator highlight that, for a modest 4 percent of the Army’s current budget, the Navy could, hypothetically, recapitalize at the rate needed, rather than plodding along its current anemic trajectory. What’s more, this reprioritization does not represent an increase in the budget top line. At the end of the day, as the U.S. Navy’s chief of naval operations has said, this is not a decision that can be made parochially but rather should be addressed at the national level by the Congress elected to make hard choices. And make no mistake, hard choices are what lie ahead — efforts to kick budgetary decisions further down the road will only lead to increasingly dire outcomes.

Blake Herzinger (@BDHerzinger) is a non-resident WSD-Handa Fellow at the Pacific Forum and U.S. Navy Reserve foreign area officer. The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and do not represent those of his civilian employer, the U.S. Navy, the Department of Defense, or the U.S. government.

Image: U.S. Navy (Photo by Mass Communication Spc. Seaman Taylor Parker)