There is a lot of war talk in the air in Washington. The frequency of China’s navy and air force activities around Taiwan has increased of late. Politicians, officials, pundits, and experts in the United States are speculating about the increased probability of a military conflict over Taiwan. Almost everyone has ideas for strengthening deterrence against a Chinese attack on Taiwan. There is no agreement, however, about how this should be done. Some argue that the United States should maintain “strategic ambiguity” in its relationship with Taiwan, whereby the scope and scale of any American military and diplomatic support for Taiwan in the event of an attack from China is deliberately unclear. Uncertainty will instill caution in China’s calculus and will remind both Beijing and Taipei that the United States does not support Taiwanese independence. Others argue for abandoning “strategic ambiguity” in favor of “strategic clarity,” whereby the United States clearly signals that it will intervene militarily to defend Taiwan.

For all the pressure inside Washington from Congress and from some of the think tank world to endorse strategic clarity, however, there is little systematic evidence to show whether strategic clarity is likely to enhance the deterrence of China’s use of force. We report here findings from surveys that we conducted in Taiwan that suggest strategic clarity could help enhance deterrence by increasing the willingness of Taiwanese people to fight, but at the same time could weaken deterrence by increasing popular support for de jure independence, thus reducing China’s confidence that the United States does not support Taiwanese independence. This suggests that in order for the United States to maximize its ability to deter China from attacking Taiwan, it should credibly communicate both resolve to use force in Taipei’s defense, and clarity about preventing Taiwanese independence.

The Competing Logics of Ambiguity and Clarity

Advocates of replacing “strategic ambiguity” with “strategic clarity” typically argue that ambiguity does not send a strong enough deterrence signal to the Chinese government and does not provide a strong enough reassurance signal to Taiwan. The net effect, the argument goes, is to increase the probability of conflict, reduce the credibility of U.S. commitments to its allies in the region, demoralize the people of Taiwan, and undermine U.S. support for a democratic government. Proponents of strategic ambiguity have long argued, however, that uncertainty can induce caution in the target state. If China’s leaders are uncertain about the scope and scale of a U.S. response to an attack on Taiwan, they may make worst-case assumptions about U.S. resolve, which in turn will help deter a conflict. And if Taiwan is uncertain about the scope and scale of U.S. support should deterrence fail and should Beijing use force to prevent independence, Taipei will be deterred from moves toward independence. If independence is deterred, China will be less likely to attempt to use force. So strategic ambiguity, better described as dual deterrence in the words of one of the key players in Washington’s Taiwan policy over the years, Richard Bush, is designed to both deter and assure the People’s Republic of China, a classic application of the logic of deterrence theorist Thomas Schelling.

While the Biden administration appears to be sticking with ambiguity for the moment, some members of Congress and Washington think tanks are increasingly advocating strategic clarity. Moreover, the recent decision to expand high-level interactions between U.S. and Taiwanese officials hints that the second leg of strategic ambiguity — assuring Chinese leaders that the United States does not recognize Taiwan as a sovereign state nor does it support Taiwan independence — is weakening.

Without access to internal decision-making information in Beijing and Taipei, it is hard to determine whether strategic ambiguity has played a role in deterring both a Chinese attack and a Taiwanese move toward independence (or either of those outcomes). But the messaging to the leadership in Beijing is known: They cannot be certain about the nature of the political and military response by the United States. The messaging to Taiwan is similarly known: The United States does not support a unilateral attempt by Taiwan to change the status quo as America defines it — namely Taiwan is not an independent state. Critics of ambiguity claim that this messaging is insufficient, that Chinese leaders are increasingly skeptical of U.S. resolve, and that Taiwan feels unsupported. The policy of ambiguity is only encouraging the Chinese leadership to use force. Clarity, on the other hand, will enhance deterrence because the United States will, in essence, tie its own hands by committing to certain intervention under all conditions — including Taiwanese independence (the proponents of strategic clarity are often ambiguous about their position on whether independence would constitute a change in the status quo).

Testing the Deterrence Effects of Strategic Clarity

It is, of course, impossible to test whether a strategic clarity policy will enhance deterrence since it has not formally been implemented. But there is a logic to strategic clarity that can be tested, namely the effect of clarity on the attitudes of Taiwanese people toward two issues related to deterring the People’s Republic of China: willingness to fight against China, and support for independence. So, as a first cut at testing the competing claims about deterrence proponents of strategic ambiguity and strategic clarity make, we conducted two survey experiments implemented in November 2019 and November 2020 in Taiwan on a random sample of the Taiwanese population. Willingness to fight is, of course, not the only source of deterrence — capabilities and operations for denial and punishment are obviously critical. But all three sides have paid a lot of attention to the popular will to resist a Chinese attack. For Chinese leaders, lowering the Taiwanese people’s will to fight reduces the costs of using force. For Taiwan, a popular willingness to resist a Chinese attack and possible occupation helps increase deterrence by denial. And, for the United States, a Taiwanese willingness to fight means the United States would not be sacrificing blood and treasure for a people unwilling to help defend themselves.

As for support for independence, one implicit hope at the heart of strategic ambiguity is to assure the People’s Republic of China that the United States will not support Taiwan’s independence. This is based on the assumption that Beijing is more likely to use force if Taiwan moves toward, or declares, independence. Evidence from past Chinese behavior suggests this is a reasonable assumption. For example, China’s 1996 military exercises and the 2007 near-crisis over Taiwan’s referendum in support of its entry into the United Nations were, in part, driven by fears that Taiwan was going to cross China’s “red line” and pursue independence. The strategic ambiguity argument is that deterrence is reduced if Taiwan believes U.S. military support is unconditional, regardless of whether or not Taiwan actually pursues independence.

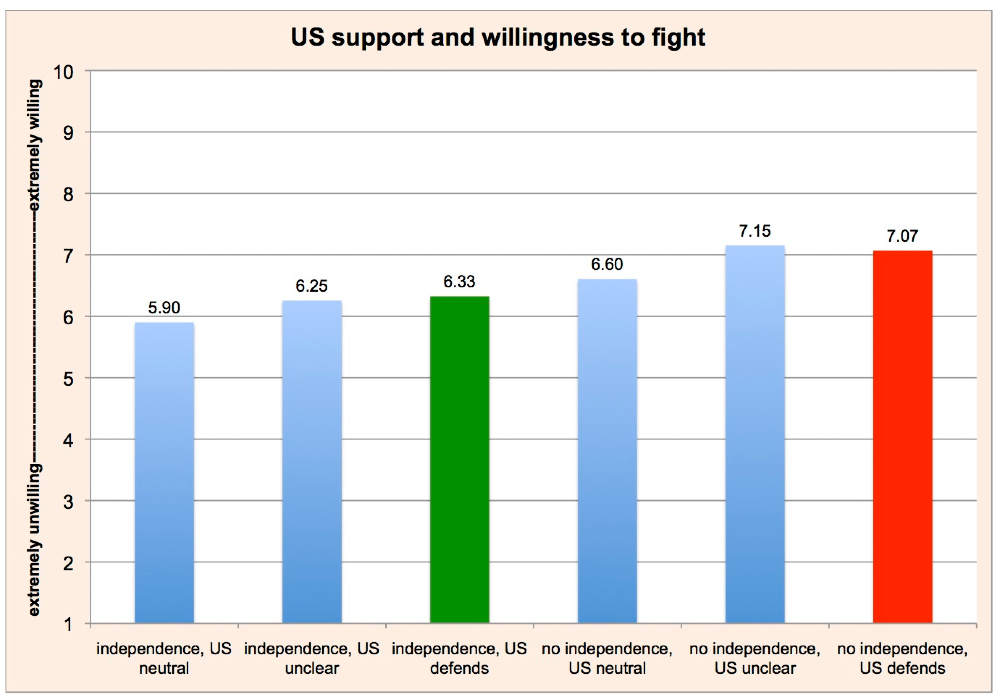

In our November 2019 survey, the primary scenario presented to respondents was that the Chinese military had attacked Taiwan. Respondents were then randomly asked about one of six hypothetical conditions that differed in the degree of certainty with which Americans would come to Taiwan’s military defense: Taiwan had already declared independence, and the United States remained neutral; Taiwan had declared independence, and the United States was hesitating about defending Taiwan; and Taiwan had declared independence and the United States had come to Taiwan’s defense. The other three conditions were similar, except they posited that Taiwan had not declared independence when China had attacked. Respondents were then asked about their “willingness to fight,” measured on a 10-point scale from “extremely unwilling” to “extremely willing.”

In the November 2020 survey experiment, the hypothetical scenarios were similar to the November 2019 survey, designed to test beliefs in the likelihood of the United States militarily coming to help Taiwan if China militarily threatened it. Respondents were then asked how likely they were to support independence after learning of the U.S. position on defending Taiwan.

Findings

Our first main finding is that the scenario in which U.S. military support was certain made respondents more willing to fight. As Figure 1 shows, for the survey sample, there is an overall increase in willingness to fight as the United States’ response moves from neutral to hesitant to intervention in defense of Taiwan. The willingness to fight is statistically lower when Taiwan has declared independence than when it has not declared independence (compare columns 3 and 6 in Figure 1). In other words, a necessary condition for enhancing any deterrence effect from an increase in the willingness to fight is that Taiwan has not declared independence. In this regard, strategic clarity would appear to be better for deterring China so long as there is no prior declaration of independence. (While it is possible that some respondents are answering strategically — aware that a willingness to fight is a good signal to send to supporters of clarity in the United States — we are doubtful that the non-sampling errors in the survey are systematically biased in that way. Taiwanese respondents are exposed and attentive to a rich media environment where these kinds of issues are debated and where individuals can form genuine opinions).

Figure 1: Variation in U.S. support and Taiwanese respondents’ willingness to fight.

Source: Chart generated by authors.

Our second main finding is that proponents of strategic ambiguity are also probably right: Confidence in American military intervention appears to increase support for independence. As Figure 2 shows, respondents’ willingness to support independence increases as the treatment shifts from uncertain American support to unambiguous military support. The proportion of respondents who are very likely to support independence in the event that China uses force rises from 15 percent to 20 percent as U.S. military support shifts from ambiguous to certain. Those who say they are somewhat likely to support independence also increases from 24 percent to 27 percent as U.S. military support becomes certain. Together, some level support for independence shifts from about 39 percent to about 47 percent. In addition, we also asked respondents what kind of military attack China was likely to undertake. The choices ranged from an attack on Taiwan, an attack on Taiwan-controlled offshore islands, a decapitation strike on Taiwan’s president, or an economic blockade. The largest portion of respondents believed an economic blockade was most likely, but the second largest group thought an attack on the island of Taiwan was most likely. It is worth noting that, for these two costly scenarios, strategic clarity increased support for independence.

Figure 2: Variation in U.S. support for Taiwan and the likelihood that respondents will support Taiwanese independence after being attacked by the People’s Republic of China.

Source: Chart generated by authors.

These results suggest that strategic ambiguity is correct in its assumption that clarity in U.S. military support risks increasing support among Taiwanese for independence. In this regard, strategic clarity may undermine deterrence because such a commitment reduces the assurance to Beijing that Washington does not support Taiwanese independence. Lack of assurance increases China’s incentives to change the current no independence status quo by forcing unification.

Conclusion

In summary, our survey suggests that the overall deterrence effects of strategic clarity are ambiguous. On the one hand, strategic clarity could enhance deterrence because it increases the Taiwanese people’s willingness to fight. On the other hand, strategic clarity could reduce deterrence because it appears to increase the Taiwanese people’s support for independence. We are not qualified to recommend policy, least of all to the United States (none of us have served in any government, and, among us, there is no consensus about policy preferences). But if one were to make the argument for strategic clarity, our findings suggest there is no clear and obvious solution that both unambiguously increases deterrence (willingness to fight) and decreases the incentives for China to use force (attitudes toward independence). Advocates of strategic clarity will have to wrestle with this ambiguity. Here, Thomas Schelling’s insights into deterrence may be relevant. Schelling argued that deterrence requires both the credible ability to punish or deny a potential aggressor, and the credible offer of assurance that the potential aggressor’s worst outcome won’t occur. Considering our findings, Schelling’s logic suggests that strategic clarity will have to be clearly and credibly conditional.

Assuming that China’s preference is to deter Taiwanese independence rather than compel unification, our preliminary evidence about the effects of strategic clarity suggests that deterrence of China’s use of force will be strongest when the United States is credibly committed both to using military force to defend Taiwan and to preventing Taiwan’s emergence as a de jure independent state.

Alastair Iain Johnston is a professor in the government department at Harvard University. Tsai Chia-hung is the director of the Election Study Center at National Chengchi University in Taiwan. George Yin is a visiting assistant professor of political science at Swarthmore College and a research associate at the Harvard Fairbank Center for Chinese Studies. He will be joining National Taiwan University this fall. Steven Goldstein is the Sophia Smith Professor of Government at Smith College Emeritus, an associate of the Fairbank Center, and the director of the Taiwan Studies Workshop at Harvard University.

The authors thank the Election Study Center at National Chengchi University and the Alan Romberg Memorial Fund at the Harvard Fairbank Center for Chinese Studies for funding, and the Election Study Center for conducting the above surveys.