Metus Hostilis: Sallust, American Grand Strategy, and the Disciplining Effects of Peer Competition with China

In May 1781, a cantankerous John Adams, still smarting after his public falling-out with Benjamin Franklin and humiliating ejection from the French court, sat down to write a stern letter to his teenage son, the young John Quincy Adams. Now based in Amsterdam, where he served as the fledgling American republic’s envoy to the Netherlands, the classically educated New Englander was intent on ensuring that his eldest boy kept up with his homework, and more specifically, with his detailed study of the greatest texts of antiquity. The doting paterfamilias urged his talented offspring to focus his intellectual energies on the works of the first century B.C. Roman historian Gaius Sallustius Crispus — more commonly known as Sallust;

You go on, I presume, with your Latin Exercises: and I wish to hear of your beginning upon Sallust who is one of the most polished and perfect of the Roman historians, every period of whom, and I had almost said every syllable and every letter is worth studying. In company with Sallust, Cicero, Tacitus and Livy, you will learn wisdom and virtue. You will see them represented, with all the charms which language and imagination can exhibit, and vice and folly painted in all their deformity and horror. You will ever remember that all the end of study is to make you a good man and a useful citizen. This will ever be the sum total of the advice of your affectionate father.

Part of a revolutionary generation steeped in the classical tradition, John Adams was hardly the only founding father to express a fierce admiration for the depth and elegance of Sallustian prose. Indeed, in 1808, an aging Thomas Jefferson would dispense remarkably similar advice to that of his great frenemy from Massachusetts, encouraging his grandson to distill from a close reading of Sallust the “valuable art of condensing his thoughts and expressing them in the fewest words possible,” adding that the Roman historian never “omitted a necessary word, nor used an unnecessary one.” This was a rare quality which made him “worthy of constant study.”

In their effusive praise for Sallust, the founding fathers were merely the latest in a succession of thinkers and statesmen, from Saint Augustine to Thomas Hobbes, who — over the course of the centuries — viewed the brooding politician as one of the late Roman Republic’s most pungent observers of domestic polarization and decline as well as its most forceful political moralist.

Especially popular in the medieval and early modern eras, Sallust’s mordant phrases were eagerly harvested by generations of admirers, liberally strewn across Florentine histories or etched across coats of arms. In the 15th century, more manuscripts of his texts were produced and annotated than of any other classical historian. One cautionary maxim, in particular, which also serves as a neat encapsulation of Sallust’s thought, appears to have acquired an almost viral quality: Concordia Res Parvae Crescunt, Discordia Maximae Dilabuntur, or “Small states grow with concord; discord causes great ones to dissolve.” The strength of the Sallustian legacy revolves around the scholar-practitioner’s treatment of the theme of public morals and civic-mindedness — a Roman élan vital whose faltering health, in his mind, had come to undermine almost every aspect of the late republic’s domestic and foreign policy.

Indeed, in addition to being one of the most accomplished wordsmiths of Latin literature, Sallust remains, first and foremost, the grim pallbearer for the slow, rattling demise of Roman virtue — a phenomenon which he famously associated with the jarring absence of a unifying threat (metus hostilis, or fear of the enemy) in the wake of the destruction of Carthage in 146 B.C. For Sallust, as for so many of his intellectual forbears and successors, great-power rivalry was fundamentally a two-level game — and it was impossible to disentangle a state’s domestic values from its foreign policy. Actions in one domain inevitably bled into the other. The existential nature of the Carthaginian threat had not only unified the Roman populace in a shared struggle; it had also provided them with a valuable counter-model — a refractive mirror against which they could continuously contrast, define, and ultimately perfect their own distinct tradition of republican governance. In the wake of the Punic nemesis’ eradication, that energizing focus had been lost, while territorial expansion and a glut of foreign money had encouraged avariciousness, licentiousness, and corruption. Widening socioeconomic disparities and incessant intestine political feuding had sapped the moral foundations of the republic, polluted its political vocabulary, and warped its statecraft. Out of this sorry state of affairs had slithered an ouroboros of decay and self-sabotage, as Rome’s increasingly dissipated and hubristic foreign policy progressively widened the republic’s suppurating internal fissures.

It is this aspect of Sallust’s hugely influential body of thought that is the most instructive for our own post-unipolar moment — his searing critique of the dangers of domestic factionalism and complacency along with his provocative defense of the disciplining or restorative virtues of peer competition. Among all the classical historians, Sallust’s ruminations are perhaps the most relevant to Washington’s current predicament, as a deeply divided nation seeks to both refurbish its battered democracy and prevail in a long-term competition against a ruthless authoritarian rival. Indeed, the former Roman senator provides some of the best insights into why American domestic renewal and a more proactive and values-based foreign policy are, in fact, indissolubly linked, rather than in tension or opposition.

Rome’s Enigmatic Pessimist-in-Chief

Sallust left us with two fully completed major works, the Bellum Catilinae and the Bellum Jugurthinum — both in the form of historical monographs — along with scattered fragments from a third, more epic history: the Historiae. Bellum Catilinae, or Catiline’s War, recounts the abortive insurrection of the noble Sergius Catilina in 63 B.C., its bloody suppression, and the dramatic trial of the plot’s high-ranking conspirators. Sallust’s second masterpiece, the Bellum Jugurthinum, or the War with Jugurtha, describes, in granular detail, a grueling six-year campaign in North Africa against an insurgent Numidian warlord, Jugurtha, from 112 to 106 B.C. The Historiae, or Histories, which regrettably remained unfinished at the time of Sallust’s death, were intended to be the historian’s great masterpiece, and the fragments we possess cover the turbulent period ranging from the death of Sulla in 78 B.C. to about 67 B.C.

Figure 1: “Cicero Denounces Catiline” by Cesare Maccari

Source: Wikicommons

Although we have only a relatively limited knowledge of Sallust’s political career, especially in its early years, we do know that he was a supporter of Caesar and served under him during the civil wars, even commanding a legion in Illyricum (the Balkans). This fact led some 19th century historians, such as Theodor Mommsen, to argue that his works, while superbly written and historically significant, had been almost irredeemably tainted by association. His flattering portrayal of Caesar, memorably depicted as a voice of reason and moderation in Catiline’s War, has been viewed as especially suspect. Others pointed to the fact that the historian, while deploring the rampant corruption of his time, had himself been accused of engaging in extortion and financial malfeasance during his tenure as governor of North Africa in the mid-40s B.C. For a long time, therefore, the image many had of Sallust was that of an embittered Tartuffe, who, having withdrawn from politics after Caesar’s assassination, had spent his final years secluded in his villa, pacing its famously luxuriant gardens, and furiously pouring his barbed disillusion onto the open page.

Contemporary classicists, however, would argue that this is a reductive way of approaching the work of such a complex and multilayered writer. There is no doubt that Sallust formed part of the extended network of clientage that gravitated around Caesar, and that — for a time, at least — he was “Caesar’s man.” Sallus was a novus homo, or “new man,” and an equestrian from the Italian countryside, and he may well have temporarily seen in the figure of Caesar the social reformist a redemptive figure for the republic, one who could overcome the more entrenched interests of the corrupt and self-satisfied higher aristocracy he relentlessly flays throughout his works. That this fact should be allowed to cast a pall over his entire body of writing, however, is a more dubious proposition. With his checkered, labyrinthine political motivations, and battered conscience, Sallust was in many ways a man of his time — and one whose life’s details still remain too enigmatic in the eye of the historian to warrant an unequivocal condemnation. And indeed, Sallust himself is remarkably forthright about his own failings — most famously in the opening to Catiline’s War, which takes on the chastened tones of a confessional, with the historian grudgingly admitting that, as a young man, he had been “led astray” by an “ill-starred ambition.”

Although Caesar is presented in a largely positive light, the overwhelming impression one derives from Sallust’s histories is that of his nuance and evenhandedness. As the late classicist Paul Harvey noted, although “[Sallust’s] histories show a democratic bias, and he sometimes distorts the facts, he is on the whole impartial and can recognize merits in political adversaries and faults on his own side.” Like a wan light trickling through a greasy windowpane, a certain pained candor filters through, lending psychological depth to his narratives and their core protagonists. There are no cartoon villains or shining paragons of virtue in Sallust’s world — for him, such neatly etched figures belonged to an earlier, less murky era. Rather, his Shakespearean portraits are treated in chiaroscuro, laboring under the weight of mixed motives and combining fine qualities with deadly flaws. As Catalina Balmaceda observes in her superb study of politics and morality in Roman historiography:

[Sallust] does not present a simple, neat account of the struggle between good and evil; the situation is much more complicated and not completely under control: the ones who are supposed to behave like heroes show signs of weaknesses and even vices; the criminals, on the other hand, display noble virtues on several occasions […]

In the midst of this caliginous political environment, writing and reading history clearly took on something of a redemptive quality. Indeed, as Sallust states, somewhat defensively, in Catiline’s War, although it was glorious to “serve one’s country by deeds,” to “serve her by words” was not “something to be despised.” History could serve a vital social function, providing future generations of citizens with a precious repository of inspiring and ethically uplifting exempla. A people severed from its past and the mos maiorum (way of its ancestors) would eventually lose its moral footing and find itself slowly sinking into the gloomy depths of its own listlessness.

In the Republic, Sallust’s great contemporary, Marcus Tullius Cicero, compared the dying Roman Republic to a beautiful painting whose once vibrant colors had slowly started to fade away. Writing in a time of even greater turmoil and political persecution, Sallust’s tone is more crepuscular. His famously distinct and much-emulated style — cutting, abrupt, and epigrammatic — is brutally elegant, his narrative continuously propelled forward by what an awe-struck Quintilian described as Sallust’s “immortal velocity.” In its very terseness and jaggedness, his prose reflects the harshness and disorder of a benighted era. It is as if the historian, grimacing and grunting with exertion, has unceremoniously wrenched Rome’s portrait from the wall to reveal the dark tendrils of mold that have crept their way across the back of the frame.

Sallust’s Theory of Metus Hostilis

Figure 2: “Battle of Zama” by Cornelis Cort

Source: Wikicommons

When, precisely, had Rome’s moral mildew set in? Famously, for Sallust, with the fall of Carthage. Over the course of the 118-year span of the Punic Wars, multiple generations of Romans had battled, at times desperately, against the polyglot hosts of a formidable peer competitor. The North African state’s sudden and total annihilation in 146 B.C. had not only been a system-shattering event; it had also profoundly marked the collective psyche of Rome’s elites, for whom the bipolar rivalry with Carthage, however destructive, had — in its very urgency — fulfilled a vital clarifying and unifying function. Sallust’s regret at Carthage’s eradication was profound and far-reaching. Indeed, for the Roman historian, the issue was not so much the act of sanguinary liquidation in and of itself — but rather, its long-term consequences. The loss of Rome’s sole remaining peer competitor had resulted in hubris and euphoric expansion, as the triumphant victor turned to the Eastern Mediterranean and finally cemented its hegemonic control over Greece and its congeries of feuding statelets. Its coffers now groaned under the weight of the plunder torn from the charred ruins of Carthage and Corinth, while a dark torrent of foreign money continuously inundated Roman politics. Unevenly distributed, this viscous flow of riches corrupted Rome’s elites and antagonized its people, reviving long-dormant class hatred and socioeconomic tensions. Private wealth, rather than merit, had become the principal measure of social standing among the nobiles, and, in Catiline’s War, Sallust is excoriating in his portrayal of their crass materialism — their “leveling of mountains,” to erect vulgar villas bloated “to the size of cities,” and their “scouring of the land and sea” to satisfy their gluttony for exotic foreign foods.

In both Catiline’s War and the War with Jugurtha, Sallust stresses the extent to which the conclusion of the Punic Wars constitutes, in his mind, a hinge point in the Roman history. In Catiline’s War, the historian memorably likens the moral deterioration that follows to a visible, almost physical process, drawing on the imagery of a virulent disease that gradually infects the Roman body politic:

When our country had grown great through toil and the practice of justice, when great kings had been vanquished in war, savage tribes and mighty peoples subdued by force of arms, when Carthage, the rival of Rome’s sway had perished root and branch, and all seas and lands were open, then Fortune began to grow cruel and to bring confusion into all of our affairs. Those who found it easy to bear hardship and dangers, anxiety and adversity, found leisure and wealth, desirable under other circumstances, a burden and a curse. Hence the lust for money first, then for power, grew upon them; these were, I may say, the root of all evils. […] At first these vices grew slowly, from time to time they were punished; finally, when the disease had spread like a deadly plague, the state was changed and a government second to none in equity and excellence became cruel and intolerable.

In the War With Jugurtha, Sallust doubles down on this theme and pines for a mythologized golden age — or plupast — when a fear-rooted internal consensus had helped channel and discipline the rambunctious Roman people’s natural ambitions:

For before the destruction of Carthage the people and senate of Rome together governed the republic peacefully and with moderation. There was no strife among the citizens either for glory or for power; fear of the enemy (metus hostilis) preserved the good morals of the state. But when the minds of the people were relieved of that dread, wantonness and arrogance naturally arose, vices which are fostered by prosperity. Thus, the peace for which they had longed in time of adversity, after they had gained it proved to be more cruel and bitter than adversity itself.

The core component of what has been described as “Sallust’s theorem” (i.e., that fear of an external enemy can foster greater national cohesion) was not exactly novel. Plato, Aristotle, Thucydides, and Posidonius had all previously identified what was perceived as a common social phenomenon. Other contemporary writers, such as Diodorus Siculus, had also pointed to the important role the Carthaginian threat had played as a restraining and disciplining factor in Roman grand strategy. And already in the Histories, Polybius, having observed firsthand Rome’s extension of its dominance over the entire oikoumene, or known world, had begun to cautiously adumbrate some of Sallust’s later critiques.

Interestingly, in the fraught months leading up to the cataclysmic siege of the Third Punic War, some Roman statesmen were later depicted as having been torn over the necessity of Carthage’s obliteration and have been — probably retroactively — credited with a line of reasoning almost identical to that laid out by Sallust almost a century and a half later. This is most famously described in the heated “debate of the figs” on the Senate floor, when Cato the Elder, brandishing a fresh and allegedly Carthaginian fig for dramatic effect, warned his fellow legislators that the city in which it had been plucked lay only three days away by sea, would always remain a mortal threat, and must therefore be destroyed. In this, he was purportedly opposed by his fellow senator Publius Cornelius Scipio Nasica, who argued in favor of continued peace negotiations and Carthage’s preservation. As Plutarch recounts in his life of Cato the Elder:

[Scipio Nasica] saw, probably, that the Roman people, in its wantonness, was already guilty of many excesses, in the pride of its prosperity, spurned the control of the Senate, and forcibly dragged the whole state with it, wherever its mad desires inclined it. He wished, therefore, that the fear of Carthage should abide, to curb the boldness of the multitude like a bridle, believing her (Carthage) not strong enough to conquer Rome, nor yet weak enough to be despised.

Cato the Elder was one of the few historical figures for whom the misanthropic Sallust appears to have professed a genuine esteem. Yet, for all of the historian’s admiration of Cato’s dour virtues and trenchant literary style, it is clear that, in the case of Carthage, he believed the warmongering octogenarian to have been gravely mistaken. As Saint Augustine would later approvingly remark, Scipio Nasica, with his tragic sensibility, had been the better connoisseur of human frailty. By voicing his concern that “security was an enemy to weak souls,” he had seen that “fear was a necessary and suitable teacher for citizens just as it is for small children.”

Even though the argument that Carthage’s destruction had indirectly led to the decline of the Roman Republic was not wholly original, Sallust went down in history as its most compelling and articulate proponent, directly influencing thinkers ranging from the Church Fathers to Machiavelli. Indeed, where the retired senator distinguishes himself from his predecessors is in his clinical dissection of the dangers of combining overwhelming military dominance with a lack of shared civic-mindedness. Perhaps most importantly, he is remarkably effective at shedding light on the interactive effects of domestic and foreign affairs, providing timeless insights on how issues such as corruption, polarization, and populism can come to permeate — or in Sallustian terminology, “infect” — both spheres of human endeavor.

Moral Decay as a Two-Level Pathology

In the eyes of Sallust, the sudden gift of uncontested primacy had been a poisonous one. Its financial, territorial, and political dividends had overstressed Rome’s administrative system, which had been ill-equipped to manage an empire of such magnitude. The citizenry, which had been so invested in their city’s struggle for survival during the dark days of the Hannibalic War, was now distracted by material pleasures and no longer had reason to pay close attention to the management of foreign policy. As a result of this ambience of solipsistic frivolity, “affairs at home and in the field” had increasingly been captured by only “a few men, in whose hands were the treasury, the provinces, public offices, glory and triumphs.” Domestic and foreign affairs were increasingly irrigated by the same brackish flows of illicit funds — something Sallust chronicles remarkably effectively in the War with Jugurtha.

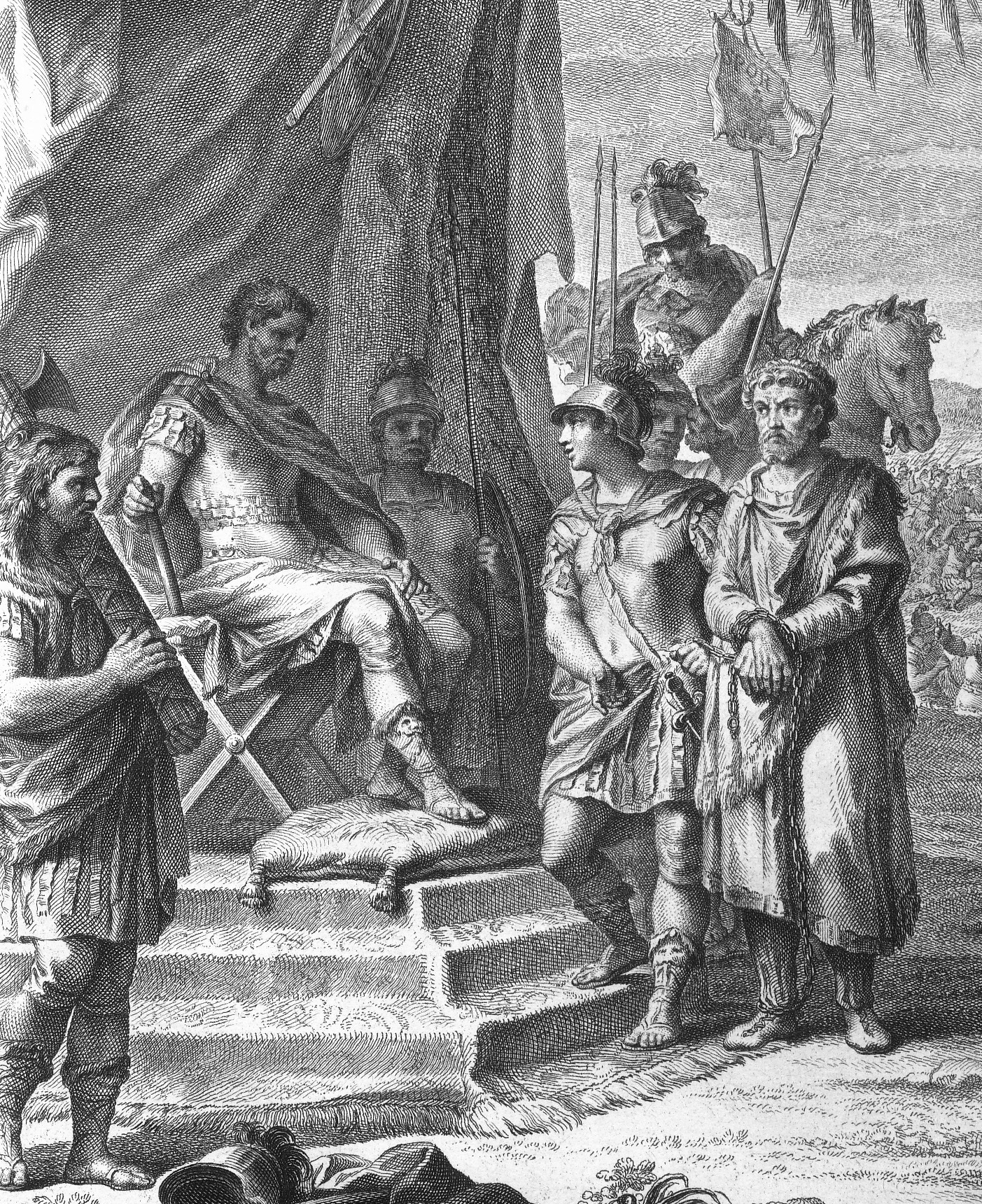

Figure 3: “Jugurtha’s Capture” by Joachin Ibarra

Source: Wikicommons

As the classicist Ronald Mellor notes, what is ostensibly a monograph on a foreign war soon morphs into a biting analysis of how Rome’s internal factional strife and corruption corroded its statecraft. Jugurtha, the adoptive son of King Micipsa of Numidia, was initially a much-respected ally of Rome, fighting alongside the Roman legions during the Numantine Wars in Spain. “Valiant in war” and “wise in counsel,” the Numidian warlord became a close companion of Scipio Aemilianus, the great hero of the Third Punic War. Over the course of the campaign, however, the ambitious young man fell into more unsavory company. A group of venal and unscrupulous Roman commanders “who cared more for riches than for virtue and self-respect, intriguers at home, influential with our allies, notorious rather than respected” began to cultivate Jugurtha’s friendship. “Firing his ambitious spirit,” they urged him to launch a coup d’état upon his return to Numidia and wrest control of the country from Micipsa’s two sons, Hiempsal and Adherbal. In an arresting moment, a troubled Scipio Aemilianus quietly takes his hotheaded friend aside and warns him not to consort with some of Rome’s more crooked elites in order to pursue his own growing ambitions. Sadly, Scipio Aemilianus’ advice falls on deaf ears, and Jugurtha, upon his return to Numidia, soon engineers the assassination of Hiempsal and launches a bloody civil war against Adherbal. Despite the blatant illegitimacy of the usurper’s actions, Rome’s response was initially hampered by divisions within the Senate, where Jugurtha’s envoys succeeded in buying off a large number of senators. Emboldened by the corruption he saw all around him, the Numidian became increasingly dismissive of Rome’s formal security guarantee to Adherbal, as “he felt convinced of the truth of what he had heard from his (Roman) friends at Numantia, that at Rome anything could be bought.”

Overly confident, Jugurtha eventually overreaches when he invades the territory Rome had allotted to Adherbal, tortures him to death, and engages in an indiscriminate slaughter of civilians and foreign tradesmen. Despite the power of Jugurtha’s “influence and money,” which threatens to protract the senatorial deliberations “until all indignation had evaporated,” the Senate “from consciousness of guilt began to fear the [Roman] people.” Gaius Memmius, a tribune of the Plebs, animated by a sense of “independence and hatred of power the nobles,” urges his compatriots to “not prove false to their country and their own liberties” by letting such an act of naked aggression against a key ally go unpunished. According to Sallust, it was only as a result of the Roman people’s righteous indignation that the aristocratic senators whose “love of money had attacked their minds like a pestilence” were finally stirred into military action against the foreign war criminal. Thereupon followed a bruising six-year campaign against the wily, elusive Numidian who, with his intimate knowledge of the Roman military, proved a formidable opponent. Sallust takes pains to demonstrate how Roman military performance was chronically undermined by the petty rivalries and grubby jostling between commanders. The fact that the war occurs on formerly Carthaginian territory also lends it a depressingly kaleidoscopic quality — immediately conjuring up unflattering comparisons with the glorious wars fought by Rome’s greatest generations across those same sunbaked landscapes.

Indeed, nested deep within Sallust’s gripping narrative the discerning reader can already see —stirring like a brood of vile grubs — the rampant corruption, knee-jerk partisanship, and toxic class hatreds that would eventually lead to the Marius/Sulla civil wars, and then, further down the road, to the end of the republic. As a survivor of vicious internecine conflicts, Sallust is less interested in their narration than in the examination of their root causes. A recurrent theme, or topos, in his work is the loss of civic-mindedness and the steady subordination of the mos maiorum (way of the ancestors) to the mos partium et factionum (way of parties and factions). As class hatreds and contending political factions grew more ossified, partisan affiliation progressively took precedence over merit. Thus, as Sallust glumly notes in the War with Jugurtha, during the two rivals Metellus and Marius’ rancorous campaign for military high office, the determining factor was not “their own good or bad qualities” but “party spirit.” Similarly, when a tribune puts forward a bill to sanction senators having accepted bribes from Jugurtha, the “commons passed the bill with incredible eagerness and enthusiasm,” not so much “from love of country” as out of “hatred for the nobles, for whom it boded trouble […] so high did party passion run.”

Figure 4: “The Discovery of the Body of Catiline after the Battle of Pistoia” by Alcide Segoni

Source: Wikicommons

One of the most interesting aspects of Sallustian thought is how, within such a charged political environment — where fellow citizens are viewed almost solely through the prism of clan, class, or faction — language itself is distorted as virtus (virtue) dissolves into vitius (vice). His commentary on the corrosive effects of the subversion of shared political vocabulary brings to mind George Orwell’s well-known later ruminations on the issue, and most notably, the English writer’s acrid observation that “when the general atmosphere is bad, the language must suffer.” Addressing his fellow senators during the Catilinarian conspiracy, Cato the Younger becomes the mouthpiece for one of the most well-known pieces of Sallustian rhetoric, lamenting the fact that words have now mutated beyond recognition and “in truth we have long lost the true name for things.”

Sallust viewed himself as a philosophical historian in the tradition of Thucydides, whose archaizing prose and penetrating psychological themes he emulated and latinized for a contemporary Roman audience. This intellectual heredity is most visible in Catiline’s War, when the historian lambasts the partisan hypocrisy now rife across the political spectrum — whether among the fire breathing populists or the reactionary nobility:

For, to tell the truth in a few words, all who after that time assailed the government used specious pretexts, some maintaining that they were defending the rights of the people, others that they were upholding the prestige of the Senate; but under pretense of the public welfare each in reality was working for his own advancement. Such men showed neither self-restraint nor moderation in their strife, and both parties used their victory ruthlessly.

As many classicists have noted, this passage is remarkably similar — indeed, in some cases, almost identical in its language — to Thucydides’ description of Corcyra’s descent into internal chaos, or stasis, in Book III of the Peloponnesian War. Both men were seasoned observers of politics, valued clear and incisive prose, and had seen in the debasement and manipulation of language clear signs of decadence and disunity.

Sallust and Contemporary Great-Power Competition

Sallust was one of the Roman Republic’s most perceptive writers on the dangers of strategic dissipation, corruption, and political polarization. What tentative insights can we draw from him today?

First of all, Sallust’s warnings of the risks tied to foreign influence campaigns and weaponized or “strategic” corruption appear especially relevant at a time when the Biden administration and several key U.S. allies have stated their determination to curb the corrosive influence of dark money and illicit financing on our democratic institutions. In the War With Jugurtha, Sallust engages in a granular analysis of how foreign lobbying and dark money undermined Rome’s statecraft, sapping it from within and preventing it from initially taking a robust and principled stance against Jugurtha’s acts of aggressions against a treaty ally. One could tease out certain eerie similarities with the Trump administration’s ethically compromised Ukraine policy, a sordid tale of sleaze, foreign influence, and corruption which eventually led to a full-blown domestic political crisis in the United States. In one striking passage of journalist Catherine Belton’s recent investigation into Putin’s kleptocratic networks of influence, a smug Russian operative is quoted as commenting on the Ukrainian scandal with the exact same words as Jugurtha in Sallust’s 2,000-year-old monograph, sneering that “[i]t looks as though the whole of U.S. politics is for sale.” Could there be any clearer indication of the timelessness of Sallust’s warnings on the pernicious role of foreign money in domestic politics or the urgency of moving forward with bipartisan anti-kleptocracy initiatives such as the Combatting Global Corruption Act?

What should one make, however, of Sallust’s controversial theory of metus hostilis, the notion that intensified great-power competition can foster greater internal cohesion?

Sallust’s theory of social change has been rightly criticized, notes one classicist, “for ignoring or downplaying earlier episodes of discord,” and for revolving around an “overly rigid,” almost mechanistic conception of historical decline. Indeed, in his nostalgia for a remote, quasi-Hesiodic golden age, Sallust often appears to be indulging in what the intellectual historians Arthur Lovejoy and George Boas memorably termed chronological primitivism — the notion that the earliest stage of human history was necessarily the most morally pristine. Interestingly, Sallust himself appears to backpedal somewhat in his final work, the Histories, conceding in one of its surviving fragments that the republic had been plagued by instances of “disputes between plebs and nobles[] and dissensions within the city” from the very beginning. Once again, though, Sallust remained convinced that it was only the presence of a common threat — that of a return of the Tarquin monarchy with Etruscan military support — that had temporarily defused these centrifugal pressures. Later, toward the mid-republic, it was the Punic Wars that momentarily “put an end to the discord and struggles between the classes,” until, with the destruction of Carthage, Rome’s citizens were “free to resume their quarrels.”

Sallust’s theory remains starkly unforgiving, almost uncomfortably so, for a modern reader. As political scientist Daniel Kapust notes, this creates a dilemma whereby “the coherence of a community may become linked to the existence of a dangerous foreign enemy.” Healthy democracies should be able to guarantee the conditions of their own success without fear of a great-power competitor, and no sensible individual would argue in favor of cultivating foreign enmity for its own sake.

And yet, Sallust’s grim insights, however unsettling, may hold some truth to them. It is possible to acknowledge that an unwelcome new strategic dispensation — the emergence of China as a redoubtable near-peer competitor — may paradoxically provide a clarifying and restorative sense of purpose to a deeply fractious American democracy. Indeed, since the end of the Cold War, U.S. security managers have frequently struggled to set clear priorities, define an overarching vision, and manage bureaucratic infighting. Meanwhile, intense domestic polarization has rendered U.S. foreign policy more volatile, unpredictable and — in the eyes of international observers — unreliable.

As contemporary political scientists such as Jennifer Mitzen and Emily Goldman have noted, physical security is not always coterminous with “ontological security,” and “relative quiescence in great-power rivalry paradoxically increases uncertainty.” Highly diverse threat environments, with little to no ordering of potential adversaries, can complicate strategic assessments, and undermine political-military coordination. Threat-based defense planning — particularly if oriented primarily toward only one or two major opponents — is less intellectually burdensome than so-called portfolio planning, which demands consistent adjudication between myriad competing risk assessments and force structure variants. The absence of a major challenger can also cause restless policymakers to elevate, and perhaps even artificially inflate, formerly second-order threats. As John Mueller has sardonically noted:

The post-Cold War jungle had snakes whereas the Cold War jungle was inhabited not only by the snakes but by a dragon as well. Some people might consider that a notable improvement and, as jungles go, a palpable reduction in the complexities of daily life. However, when big problems (dragons) go away, small problems (snakes) can be elevated in perceived importance.

The urgency of the China challenge has already led not only to a downsizing of America’s formerly open-ended commitments in other theaters but also to demonstrations of bipartisanship that have remained more elusive in other areas of foreign policy. Although the U.S. public remains depressingly tribalized, a shared, albeit belated, recognition of the fact that competition with China requires internal as well as external balancing has given birth to some surprising new manifestations of cross-party consensus — such as on the need for the U.S. to devise a more robust industrial policy or revive its moribund infrastructure. It would appear, therefore, that Sallust’s assessment of a peer competitor’s elucidating function and dampening effect on the “spirit of faction” has proven to be at least partially correct.

That being said, there are also certain key risks tied to rigidly subscribing to the theory of metus hostilis. By viewing every geopolitical development through the prism of a bipolar rivalry, American defense planners might neglect or underestimate secondary theaters along with other less formidable, but still consequential, challengers. By construing every regional crisis as a test of national will in a globe-girdling struggle with China, analysts in Washington also risk overly simplifying local conditions and disregarding the value and agency of small and mid-ranking powers. Last but not least, couching the U.S.-China relationship solely in terms of geopolitical enmity risks encouraging less wholesome and more nationally divisive sentiments. During certain periods of the Cold War, for example, thinkers such as Rienhold Niebuhr warned of the “spiritual aberrations which arise in a situation of intense enmity” amidst a “public temper of fear and hatred.” The ugliness of certain current developments, from a recent explosion of anti-Asian xenophobia and violence to misguided attempts, in some quarters of the previous administration, to frame the U.S.-China rivalry in “civilizational” terms, serve as a valuable reminder that a spirit of knee-jerk hostility toward a foreign competitor can engender its own unique set of domestic perils.

All of which brings us to the final, and most essential, aspect of Sallust: the importance of grounding foreign policy in clear values and of continuously reminding the American people that their nation’s struggle lies with the People’s Republic of China’s ideologically driven revisionism rather than with the Chinese people or some antiseptically framed Asian great-power rival. Indeed, distinguished Sinologists have repeatedly drawn attention to the ideational drivers behind Beijing’s assertiveness and vision in which “tianxia [imperialism with Chinese characteristics] meets Leninism,” with the latter’s traditional focus on power, cynicism, and subversion. To this mixture one might add an unhealthy dose of Han chauvinism, which is reflected not only China’s abhorrent treatment of its own ethnic minorities but also its disdainful attitude toward fellow Asian states. Meanwhile, Chinese officials and spokespeople regularly take to social media to tout the purported superiority of their political system and heap scorn on American democracy. Earlier this month, the Chinese Communist Party announced a new campaign of “patriotic education” aimed at purging “Western ideas” from primary and secondary school libraries.

And yet — somewhat astonishingly — calls have been growing in some quarters of the U.S. academic and policy community to sideline, minimize, or deny the role of values in Sino-U.S. competition, almost as if American government officials could singlehandedly erase or redraw the conflict’s preexisting ideational parameters. Some have even drawn haphazard historical parallels — arguing that the U.S. should seek to promote an alternative “international governance architecture” in the form of “an informal steering group” incorporating China and loosely modeled on the supposedly ideologically ecumenical Concert of Europe. These efforts are both historically and strategically unsound.

Indeed, a close reading of the history of protracted great-power competition reveals that virtually all such contests either fuel or stem from profound ideological differences. One of the key reasons why many enduring rivalries exist is precisely because preexisting ideational divergences, often driven by non-instrumental motives, frustrate bargaining and preclude mutual accommodation. For instance, one cannot comprehend England’s multigenerational rivalry with France during the Hundred Years’ War without also taking into consideration the potency of Angevin revanchism on the one hand and French royal exceptionalism on the other. Similarly, one cannot come to a full understanding of Franco-Spanish statecraft during the Italian Wars without acknowledging the fact that both powers’ competing strategies of primacy were often undergirded by millenarian and messianistic beliefs. Meanwhile, the notion that the Concert of Europe was unideological would flummox any serious 19th century historian — after all, the grouping was initially founded as an alignment of hereditary monarchies who sought not only to establish a European balance of power but also stymie the spread of revolutionary and liberal movements across the continent. Some of today’s self-designated “realists” seem to have forgotten what the Old World’s first articulators of realpolitik had clearly understood — that man, for better or for worse, is a fundamentally ideological creature. From time immemorial, the burdensome duty of any statesman has consisted of gingerly weighing the balance between their country’s material and ideational interests, all while striving to find a way to reconcile the two. As Robert Osgood, one of the more sophisticated thinkers of the Cold War, once observed:

The utopian, anxious to assert the claims of idealism and impatient with reality, or the realist, exasperated by the inability of the utopians to perceive the reality of national egoism, may be tempted to simplify the troublesome moral dilemma of international society by declaring that ideals and self-interest are mutually exclusive or that one end is the only valid standard of international conduct. […] But […] in very few situations are statesmen faced with a clear choice of national self-interest; in almost all cases they are faced with the task of reconciling the two. [..] To recognize the points of coincidence between national self-interest and supranational ideals is one of the highest tasks of statesmanship.

This holds even more true for democracies, whose leaders are accountable to their electorate, and who — in order to muster the requisite support for a policy of protracted competition — must appeal to both reality and ideology, and, in so doing, “combine the two strains not only in their speeches but in their soul.” As a recent Pew poll shows, the clearest bipartisan consensus with regard to America’s China policy is in the field of values, with over 70 percent of Americans expressing support for promoting human rights in China, even if such support should jeopardize economic relations with Beijing. As Sallust well knew, no great power can muster the will and determination to prevail in a multigenerational struggle without drawing on such inner reservoirs of moral strength. Like the Roman Republic of old, America has its own “mos maiorum” — one inextricably bound up with the universalist ideals of its classically educated founding fathers.

The notion that American foreign policy elites can disregard this fact and pursue some desiccated brand of academic realism toward China, whereby America’s democratic values are somehow surgically removed from its grand strategy, is whimsical. It is an Olympian fantasy — an elitist vision of statecraft untethered from the messy complexities of domestic politics and of human nature more broadly, and therefore, from geopolitical reality. It is also self-defeating. The People’s Republic of China is certainly a formidable adversary, capable of exerting enormous political and cultural influence through its financial clout and brute economic force. In the field of public diplomacy, however, its current leadership provides Washington with an ideal sparring partner. Brash, vulgar, and profoundly unappealing, Beijing’s ideological commissars display little of the sophistication or agility so characteristic of their more worldly Russian counterparts. Why should the United States refuse to compete in an area in which its vociferous opponents are so comically inept and in which — for all its very real challenges and flaws — America holds an overwhelming advantage?

Washington’s most capable partners in Asia are all robust democracies, frontline states that will increasingly be required to justify to their domestic populaces the growing military costs of their alignment with the United States. Absent a continued emphasis on the threat posed by Beijing to our shared democratic values and cherished international norms, the elected leaders of these states are unlikely to be able to muster sufficient levels of domestic support for more forward-leaning defense postures. Granted, some authoritarian regional actors such as Vietnam might be discomforted by a more values-driven U.S. foreign policy. Vietnam’s attitude toward its Chinese neighbor, however, is colored by a long and complex history — one in which an ardent Vietnamese nationalism has traditionally played a much more consequential ideological role than the shared communist authoritarianism of Beijing and Hanoi’s ruling classes. Vietnam will continue to independently balance against the behemoth at its borders, regardless of the nature of American public diplomacy.

Moreover, Washington can adopt a more measured and tailored approach to value promotion, countering authoritarian disinformation and corruption, and highlighting the benefits of its model without “ranging over the world like a knight-errant, protecting democracy and ideals of good faith,” or arguing in favor of regime change. It is possible to selectively partner with some authoritarian states while systematically privileging the democratic allies who also happen to be the most militarily redoubtable actors in the region. This is what the 16th century humanist Justus Lipsius famously called “prudentia mixta,” or “mixed prudence,” combining the “good and pure liquid” of values with “the sediment” of interests. As Sallust forcefully argued, though, it remains impossible to disaggregate the two. Protracted competition with China must be tied to domestic political renewal — jolting a complacent and polarized American populace into recognizing its shortcomings, rediscovering its first principles, and striving toward a more perfect union. Absent such a collective restorative effort, the great American experiment risks falling prey to the “way of faction” so powerfully depicted by one of Rome’s greatest historians.

Iskander Rehman is the senior fellow for strategic studies at the American Foreign Policy Council, where he leads a research effort on applied history and grand strategy. He can be followed on Twitter: @IskanderRehman.