Ending the Endless Wars: A Strategy for Selective Disengagement

A majority of U.S. veterans and the public do not believe the efforts in Afghanistan and Iraq were worth the sacrifice. Indeed, after nearly 20 years of overreliance on the U.S. military to fight terrorism and insurgencies worldwide, the Afghanistan intervention has not only been costly in lives and cash, but arguably counterproductive. Indeed, terrorist attacks hit 63 countries in 2019, while terrorist threats to the United States are greater today than they were in 2002. This is in large part as a result of kinetic diplomacy: the habit of responding to terrorist violence with a strategy that overrelies on military violence.

In light of America’s pending drawdown from Afghanistan, all of this raises the question — how can the United States disengage from unpopular, counterproductive military missions in a way that does the least amount of near-term damage to U.S. interests?

In my view, Washington should focus on blocking insurgent access to financial resources; acting in concert with international organizations like the United Nations; including (where possible) representatives from civil society in negotiations; limiting the number of “veto” actors who can block the peace process ending the violence and war; integrating soon-to-be-former insurgents into the political process in exchange for de-escalation; and reintegrating insurgent combatants who wish to remain warriors into the postwar state’s military, while reforming its security sector. None of these objectives — individually or as a whole — is easy. However, these best practices would advance U.S. counter-terrorism interests more effectively than continuing to accept a near permanent U.S. military presence in South Asia and the Middle East.

Admitting Failure in Afghanistan Is Necessary, but Not Easy

While the West won the Cold War, the United States has lost a lot of hot and faux wars since World War II. It lost the Vietnam War, and failed to win the peace after its Iraq intervention of 2003. The United States lost its wars on drugs and poverty, and its “Global War on Terrorism.” And in Afghanistan, Washington has failed to achieve any of its original objectives, including the destruction of terrorist recruitment and training habitat, an end to oppressive Taliban rule, and an end to opium production. Each U.S. defeat has shared the same basic pattern: the application of the wrong mix of tools to achieve a shifting political objective. Moreover, it has created systems of violence and war that have come to define the United States as a nation, a situation that President Dwight D. Eisenhower warned about in his farewell address six decades ago. Above all, since World War II, U.S. losses in hot wars tend to result from an overestimation of the coercive effectiveness of its military capabilities.

In the case of U.S. and coalition intervention in Afghanistan, the adversary’s center of gravity revolved, as it often does, around understanding what the various component groups that make up that nominal state want and fear. Two problems prevented this critical knowledge from being deployed to protect U.S. interests in Afghanistan. First, why bother getting to know an adversary’s wants and fears if death or serious injury can be relied upon to effect coercion? “Getting to know people” is time consuming, and U.S. publics tend to be promised tangible results now. Moreover, the United States has a significant investment — sunk costs — in armed forces brilliant at killing without being killed. Second, what if those wants and fears end up being offensive to an intervening actor’s core values, such as the status of women, a nondemocratic leadership selection process, or an economy dependent on support for the global trade in heroin?

In Afghanistan, the United States has relied excessively on military force to succeed, and insisted on measuring success in rapid, tangible, physical effects as opposed to, as Sir Robert Thompson famously put it, legitimacy (legitimacy tailored to its indigenous social, cultural, and political context). Obviously, some armed force is indispensable in any coercive strategy, but leading with it is a mistake.

So the international forces cannot win, but as in most military interventions since the end of the Cold War, losing has become politically unacceptable. As this became clear in Vietnam, Henry Kissinger shifted his definition of vital U.S. interest from anything intrinsic to “credibility.” Today credibility is linked with national identity. As Gen. George S. Patton made clear: “That’s why Americans have never lost and will never lose a war; for the very idea of losing is hateful to an American.” Admitting defeat risks admitting that the United States makes mistakes. Its best intentions end in unfortunate consequences perhaps only slightly less often than they do in other nations. A political leader who admits defeat in a war may put not only her own political career into the shade, but alter the balance of partisan power for years to come. This is the main reason admitting failure is so difficult.

The pressure to avoid responsibility for harm to U.S. national identity most often results not in an admission of national failure, but in two very dangerous deflections. The first is what right-wing Germans in the 1920s referred to as Dolchstoßlegende, or the stab-in-the-back myth. Our military couldn’t have been responsible for losing the war in Afghanistan. Instead, it must be the fault of civilian government officials. To be fair, civilians — not servicemembers — are in charge of U.S. defense policymaking. Nevertheless, this sort of deflection never dies. It powered the “who lost China?” debate in the 1950s. It still plagues the scholarship and historical memory of the U.S. intervention in Vietnam’s civil war. When George W. Bush faced a collapse of U.S. public support in 2006 for the second U.S.-led Iraq intervention, he promised that if the American people no longer had the backbone to see it through, his administration would not let the U.S. military down by withdrawing short of “victory.” This same deflection will follow the departure of international forces from Afghanistan as well, with U.S. chicken hawks — having spent all of the Trump administration decrying the presence of international forces in Afghanistan — now blaming the administration for spinelessness and betrayal of America’s brave troops for attempting the same withdrawal.

The second deflection is equally dangerous. It asserts that since all rational human beings must fear physical death or serious injury above all else, and America’s killing failed to achieve coercion, it must be that we faced not rational human beings but irrational animals in human form. In World War II in the Pacific, kamikaze attacks and the Battle of Attu convinced Americans and their Western allies that the Japanese were not human adversaries, but beasts who had to be exterminated. In the U.S. intervention in Vietnam, communist battlefield losses as a proportion of prewar population were 2.5 to 3 percent, almost historically unprecedented. The question of how the Vietnamese communists could continue to resist U.S. coercion after sustaining such losses was called the “breaking point” debate. After 9/11 — another suicide attack — this association of an adversary not fearful of death with irrationality became, and remains, a dominant view.

There are real benefits to admitting failure. First, nations — like people — learn when they acknowledge mistakes. Second, after the U.S. intervention in Vietnam, the United States began to accept a broader definition of the costs of war — one that incorporated psychology and emotion as well as physical injury, death, and material opportunity costs. The country began to understand and then acknowledge that the costs of war do not end when the fighting stops and the smoke clears, but can continue for generations afterward as post-traumatic stress disorder and moral injury.

What Is Needed Now: Selective Disengagement

The United States can reduce the long-term damage of its failure by returning — as the Biden administration appears to be doing — to an investment in the two key pillars of international peace and prosperity it helped build after World War II: collective security (e.g., NATO and bilateral defense treaties with Japan, South Korea, and Australia), and international institutions such as the United Nations, World Trade Organization, and International Monetary Fund. That is reengagement, and it needs to happen regardless of whether the United States will end up paying disproportionately more than its allies. Disengagement should take the form of ramping down U.S. military interventions abroad, rebuilding the U.S. State Department, and reestablishing the principle that a resort to arms is not a first but a last resort.

Here I make my case in two parts: first, by establishing that since 9/11 the United States has dramatically departed from traditions that supported its continued security, prosperity, and leadership globally. And second, by highlighting the serious shortcomings of its recent policies in Afghanistan as a way to understand the “how” of disengagement.

A Brief History of Recent U.S. Military Intervention Efforts and Their Outcomes

Since the end of World War II, most U.S. military interventions have not gone as expected, and more importantly, have undermined U.S. interests. Starting with the Korean War in 1950, then moving on to intervention in the Vietnam War, U.S. military interventions began to fit a pattern: Coercing an adversary by threatening to kill a lot of their soldiers, sailors, airmen, and the like seemed to become more difficult. In the Gulf War, by contrast, the United States led a coalition that rapidly and decisively attained its military objective: the ejection of Iraqi armed forces from Kuwait. What the United States learned from this success was summarized in a now well-known essay in Foreign Affairs by then-Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Colin Powell. Now known as the “Powell Doctrine” (an update of 1984’s “Weinberger Doctrine”), it asserted that there were actually two sorts of military intervention the United States might pursue. One sort, an intervention in an internal armed conflict featuring irregular armed forces in vehicle-impassable terrain, was to be avoided at all costs. According to Powell, a veteran of the Vietnam War, these “small wars” were not the sort of wars the U.S. military had been designed to fight and win. The second sort of war — a war against an internationally recognized state fielding regular armed forces — would be the kind of war the U.S. military could be counted on to fight and win both decisively and with relative ease, so long as that state was not a nuclear-armed advanced industrial state such as the Soviet Union.

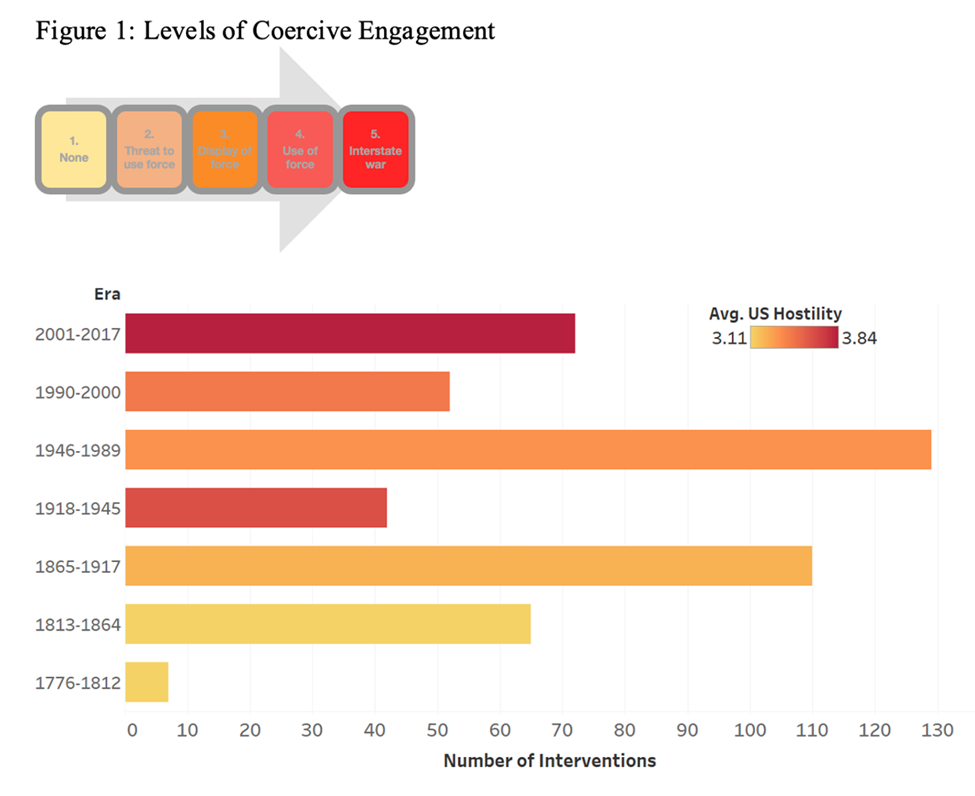

Of course, Powell’s effort to dissuade the United States from intervention in future small wars was not successful. Since the end of the Cold War, and in particular since 9/11, the United States has increasingly undertaken the first sort of intervention: deployments to war-prone territories that feature fractured polities and instability, often the conditions that are claimed to necessitate military intervention in the first place. Using data from the Military Intervention Project I direct at the Fletcher School, Tufts University, Figure 1 outlines the number of U.S. coercive engagements across different historical eras (e.g., the Cold War) and the physical intensity — labeled as “level of hostility” — of those interventions: from no use of force, to threat of force, to the use of force below the threshold of outright war, to, finally, interstate war.

Source: Graph generated by the author.

Not only has the United States intervened abroad more frequently in the post-Cold War period (note that they are shorter periods, totaling nearly half the number of years of the Cold War period), but it’s done so with more intensity. So, while America’s adversaries have increasingly sought to de-escalate fights, the United States has ramped up its use of force.

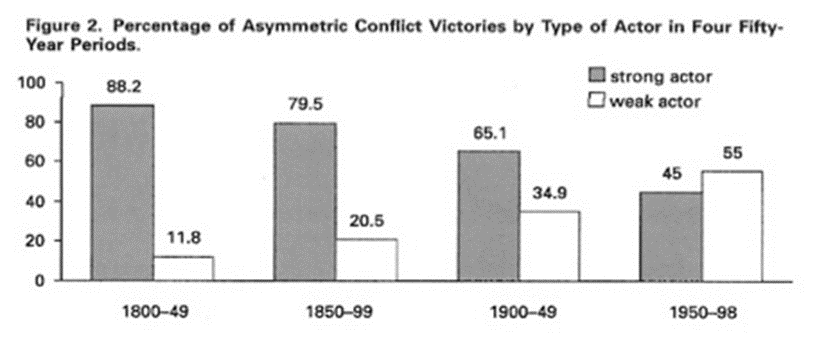

While these interventions are often conceived of as short-term military missions, intended to resolve a specific instability, they almost invariably escalate into the never-ending wars and deployments we have seen in Iraq, Syria, and Afghanistan. And as political scientist Ivan Arreguín-Toft has documented, powerful states like the United States have been losing them more often since the 19th century.

Source: Ivan M. Arreguín-Toft, How the Weak Win Wars, Cambridge University Press, 2005.

Research spanning over 200 years of asymmetric conflict outcomes makes it clear that the days in which it was possible to succeed in a military intervention of the kind the United States increasingly undertakes have long since passed. In the future, there should be a recognition that military intervention — intervention which presupposes that effective killing equals effective coercion — is unlikely to produce the final outcome sought after, and will, at best, create a true foreign policy dilemma.

So if nonintervention is intolerable, but military victory is impossible, how should the Biden administration approach the tough goal of advancing U.S. national security interests while demobilizing its armed intervention in Afghanistan? How can the Biden administration disengage from Afghanistan without tarring the Democratic Party with the inevitable claim from the political right that “the war could have been won, but for the cowardice of politicians Washington” (in other words, the stab-in-the-back claim)?

How to Disengage: Six Tools

Given the current hyperpolarized political climate in the United States, a stab-in-the-back claim against the Biden administration is overdetermined, but these six tools for constructive disengagement are the Biden administration’s best chance to manage Richard Falk’s dilemma in the context of the failed U.S. military intervention in Afghanistan (these would apply in other contexts too, including Yemen and the counter-ISIL efforts in Iraq and Syria). By “constructive,” I mean disengagement that mitigates the costs of America’s defeat in Afghanistan not only to U.S. and allied interests, but to those of the Afghan people going forward. These tools are: (1) blocking insurgent access to cash; (2) acting in concert with international organizations like the United Nations; (3) including (where possible) representatives from civil society in negotiations; (4) limiting the number of veto players; (5) integrating soon-to-be-former insurgents into the political process in exchange for de-escalation; and (6) reintegrating insurgent combatants who wish to remain warriors into the postwar state’s military, while reforming its security sector.

To its credit, the Biden administration has already initiated policies consistent with constraining Taliban financing, including Afghan civil society in negotiations, and reforming the country’s security sector.

Tool 1: Interdict Insurgent Access to Cash

The Taliban have a diverse revenue portfolio. They annually earn an estimated $200 million from “drug processing and taxation,” as well as further revenue from illegal timber and pistachio harvesting. Additionally, the Taliban are supported by Islamic charities.

The traditional issues in targeting Taliban finances do not derive from identifying revenue streams, but rather in locating financiers and building a cooperative system to target the Taliban financial system. Although significant gains have been made in identifying and freezing the assets of illicit charities, these international efforts have not been synchronized and often do not include the Gulf states — the primary source of zakat money redirected toward the Taliban and other Islamic extremists. Other efforts to disrupt Taliban drug processing and taxation have included increasing coalition security force presence in Taliban territory, as well as bombing heroin production facilities. The success of current efforts has been intermittent, however, as the simple Taliban labs can be easily rebuilt.

The first step in curtailing Taliban revenue streams is to eliminate foreign funding sources, especially Islamic charities. The only way to do this is through an international, cooperative effort. The most likely leader of this effort would be the United Nations. European, North American, and Arab states alike need to quickly identify illicit charities and immediately freeze assets. Intelligence sources need to be used to identify and detain terrorism facilitators who operate through the informal, cash-based (hawala) networks in the Middle East.

The second step is long-term rural economic reform to steer the Afghan economy away from heroin production. Studies have shown that airstrikes are unsuccessful because drugs are often removed from the targeted location, and the airstrikes harm rapport between coalition forces and farmers. Further, hoping that the market for heroin in Europe and North America will subside is a folly. Instead, Afghan farmers should be licensed to grow poppies, and the international community needs to support the procurement of these poppies for medical purposes. Similar measures in Turkey and India were successful in significantly reducing, or eradicating, illicit opium trade.

The third and final step is to target and detain Taliban tax officials. Targeting these individuals prevents the Taliban from collecting taxes in rural Afghanistan. This action could be done by Afghan security forces, with intelligence support from foreign allies. Afghan security forces need to be cognizant of local rapport, therefore their presence in rural areas is integral. Outside states, however, are more likely to be viewed as interlopers, therefore outside interveners should focus on intelligence and other support.

Tool 2: Act in Concert with International Organizations

The United Nations currently is not leading the Afghan war settlement process. Instead, Qatar has hosted the U.S.-Taliban peace talks. The United Nations approved the settlement, but this happened after the Feb. 29 deal was already signed. Instead of Qatar and the United States leading the process, the United Nations needs to take ownership over the process (especially given the reputation of the former and the cobelligerent status of the latter). Afghanistan is not a member of any regional organizations, and the various intermediate powers with a Central Asian presence do not have enough rapport among the belligerents to unilaterally lead negotiations. Therefore, it is incumbent upon the United Nations to lead the settlement process.

As part of leading the peace process, the United Nations should also be the primary actor in economic and security actions. Although the original NATO deployment is noble in scope, the United Nations should be leading any military presence under blue flags. Over 90 countries lost citizens in the Sept. 11 attacks. Global jihadism affects all countries. U.N. peacekeeping would redirect Afghan conflict mediation toward multilateralism, instead of the current U.S.-centric interventionism. Of note, U.N. peacekeeping should be framed around a peace settlement, rather than a pure military intervention.

Tool 3: Include Civil Society in Negotiations

Afghan civil society includes a range of professional, religious, and community organizations. However, they have largely been absent from the peace process. Instead, civil society in Afghanistan tends to operate on the margins of the conflict. The peace process — which should ideally be led by the United Nations — needs to actively involve civil society in order to address the grievances that have resulted from the many decades of internal Afghan strife. Further, civil society can be leveraged to lead community reintegration, supporting and carrying out the terms of the peace settlement.

Tools 4 and 5: Limit Actors with Vetoes and Integrate Insurgents into the Political Process in Exchange for Rejecting Violence

The current peace negotiations involve the Taliban, Afghan government, and United States. Although the Islamic State-Khorasan franchise is not represented, it would be quickly defeated by a unified Afghanistan, and therefore should not be given a role. Further, the current involvement of the Taliban in the peace process is a significant progress metric, and the ongoing discussions of Taliban government inclusion needs to be predicated on reducing levels of violence. The international community is following these two lessons through its use of diplomatic tools.

Tool 6: Integrate Non-State Combatants and Reform State Security Sector

Afghanistan is heavily militarized. There are hundreds of thousands of Afghan combatants between the Afghan security forces, Taliban, Islamic State-Khorasan, and other militant groups. As part of any peace process, these combatants need to be disarmed, disbanded, and reintegrated and the security sector reformed. Some of the former Taliban and other jihadi militants will need to be integrated into the Afghan National Army. The Afghan National Army, already too big, needs to refine its structure in order to absorb reformed Taliban.

There are several issues for special attention in a holistic Afghanistan disarmament, demobilization, and reintegration process, which should go along with a security sector reform process. First, commanders of both militant organizations and state security forces need to be included in the demobilization and security sector reform processes. These commanders have led decentralized campaigns for years, but if integrated into a reformed state system, these commanders should cooperate with national guidelines. Moreover, the individual combatants need to be provided with livelihoods and hope. For example, a program among Palestinians revealed that cash and brides can help to demobilize terrorist fighters. Second, transitional justice needs to be addressed as part of larger reforms in Afghanistan. Third, the reintegration and reform processes need to include a combination of cultural and economic tools, reforming mindsets and building skill sets. Only in this manner can the ex-combatants fully rejoin society.

Conclusion

While U.S. military intervention remains a critical tool of statecraft in support of U.S. national security and prosperity, its overuse since 9/11 has resulted in grave harm to both U.S. national security and prosperity. The United States needs to be more restrained in its use of force. Here I have introduced the case of the U.S. intervention in Afghanistan after 9/11 as a foil for why even well-resourced military interventions so often go wrong, and how efforts to disengage to achieve stable peace can fail as well. Nevertheless, there are a range of disengagement policies that can advance U.S. and allied interests in Afghanistan. These six approaches would apply equally well (with different details) to disengagement in other theaters as well. The costs of disengagement often seem high (and they are), but they are manageable relative to the costs of continuing to limp forward. Americans also have to think long term (as America’s adversaries very often do).

The war in Afghanistan actually began over four decades ago with the assassination of Muhammed Da’ud Khan in 1978. Its resolution will not follow the departure of American and allied troops and will take decades. Above all, Afghanistan cannot be managed by foreigners, and the country is unlikely to satisfy a Western conception of a legitimate government.

Monica Duffy Toft is a professor of international politics and director of the Center for Strategic Studies at the Fletcher School at Tufts University. She is also a nonresident fellow of the Quincy Institute and a global scholar of the Peace Research Institute Oslo.

Image: State Department (Photo by Ron Przysucha)

Correction: An earlier version of this article incorrectly referred to the current security mission as the International Security Assistance Force. In fact, the current NATO-led security mission in Afghanistan is Resolute Support.