Join War on the Rocks and gain access to content trusted by policymakers, military leaders, and strategic thinkers worldwide.

In March, the South Atlantic witnessed an unusual scene: a U.S. ship turning around and sailing for home, having been refused docking rights and services by the Argentine Ministry of Foreign Affairs. From January to March, the U.S. Coast Guard deployed one of its newest cutters, the USCGC Stone, to the South Atlantic, with the mission to strengthen maritime security relations and help curb illegal fishing — predominately Chinese — off the South American coast. This was the Coast Guard’s first such regional deployment in over a decade, and its first three-quarters were a success, training and cooperating with the maritime forces of Guyana, Brazil, and Uruguay. In Argentina, however, the mission hit a snag when the government refused to provide the dock services that are routine for such a visit.

The press paid little attention to this kerfuffle, but it was yet another sign that a tectonic shift is underway. In the South Atlantic, former U.S. security partners are building stronger ties with China, a shift that presents critical future risks for Washington and the inter-American community.

China’s Growing Presence in the South Atlantic

Over the past 20 years, China’s trade and investment with South America has surged, and it is now the region’s top trade partner. China’s Maritime Silk Road envisions a global network of Chinese-managed ports and sea routes flowing with Chinese cargo. Chinese companies have invested in ports and related services on South America’s Pacific Coast and in the Caribbean, and now it understandably seeks greater access to the region’s south-central breadbasket east of the Andes. A Chinese company operates Brazil’s second-largest container port in Paranaguá, and China plans to build a massive port to the north, in São Luis. In Uruguay, a Chinese fishing group aims to build a $200 million port in Montevideo capable of supporting 500 fishing vessels at a time.

Relations with Argentina are especially advanced. Over the past decade, China has financed and built a major railroad and solar, wind and nuclear energy projects and has swapped $19 billion in currency to help Buenos Aires through a major financial crisis. In exchange, Argentina opened its markets and industries to Chinese goods and investment. Concerned about food security for its booming middle class, China has invested heavily in Argentina’s beef and agro-industry; China’s COFCO is now Argentina’s leading agro-industrial exporter.

Argentina’s reliance on China is likely to deepen. The Paraná-Paraguay river system carries over 75 percent of all Argentine and Paraguayan exports to the Atlantic. Argentina needs to have it dredged and its facilities improved, and the Shanghai Dredging Company, a subsidiary of state-owned multinational China Communications Construction Company, plans to bid on the project. Judging from the case of the Chinese port in Piraeus, Greece, where the state-owned global shipping firm COSCO has interwoven liner and port services and has squeezed out Greek competitors, Chinese dominance in the waterway could give Beijing enormous political leverage across the Southern Cone.

Yet China’s strategic relationship with Argentina is not limited to business and trade. The financial bailout deal included permission to build a space research and satellite-tracking station, run by the People’s Liberation Army, in Argentina’s high desert province of Neuquén. Recent talks have included the potential sale of Chinese fighter jets and armored vehicles and the refurbishment of an Argentine naval base in the far south capital of Ushuaia.

There is a clear economic rationale for China’s investments in Argentina, a nation rich in agriculture, beef production, minerals, and maritime resources. But Beijing may also have long-term strategic calculations in mind: the securing of access to two continents and two seas.

Maritime Disputes and Antarctica Claims Offer Strategic Opportunity

Rich with resources, the South Atlantic offers various opportunities for China to exploit its strategic weight. Off the South American and West African coastlines lay vast undersea oil and gas fields, and the region’s waters are rich in biodiversity. Furthermore, the continent of Antarctica — where the Antarctic Treaty prohibits resource exploration or development — remains untapped. Future access to the continent and several nearby islands is under dispute, with multiple countries asserting rights to the resource-rich area.

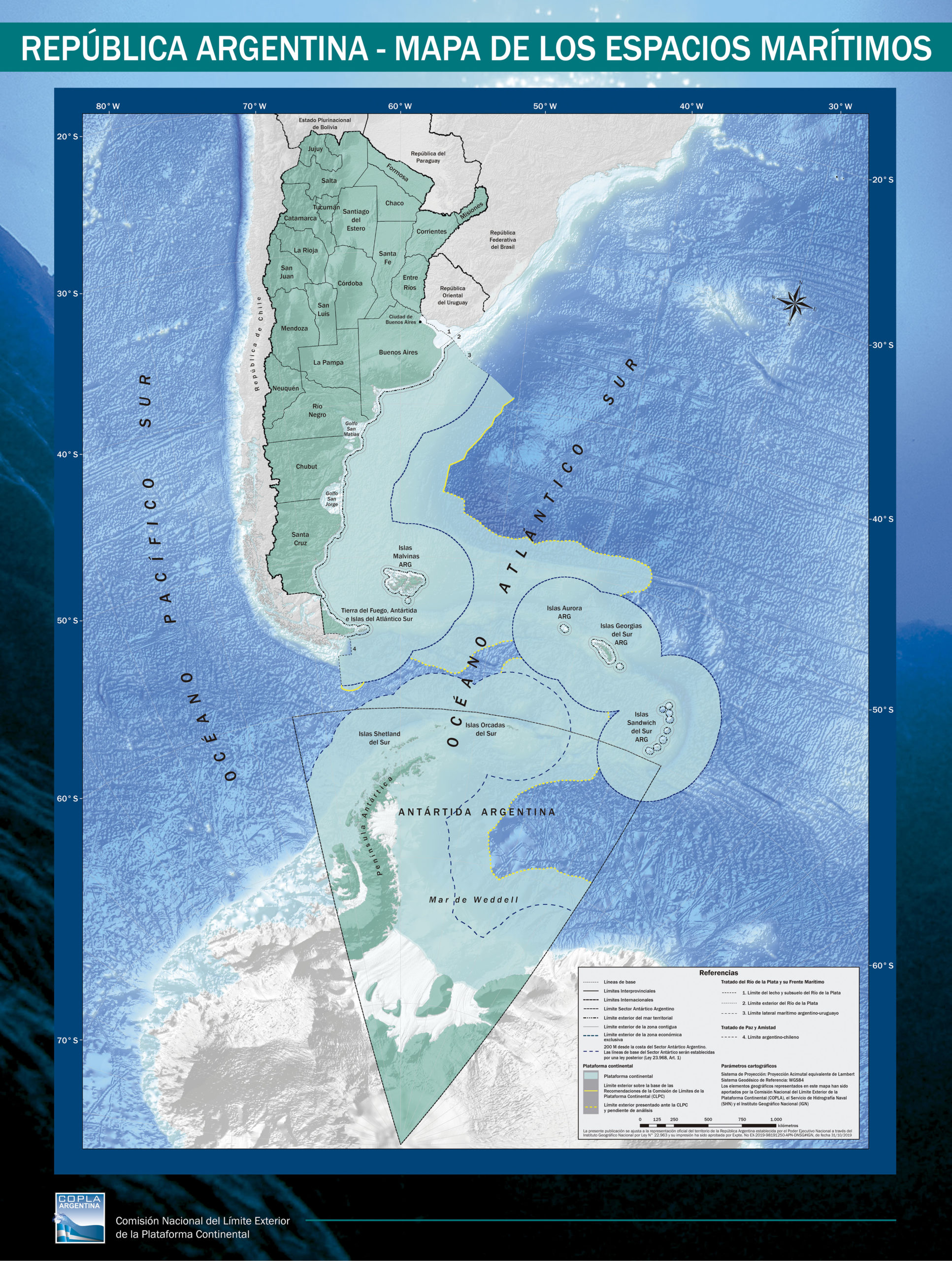

From the perspective of the United Kingdom, any question over the sovereignty of what it calls the Falklands and Argentina calls the Malvinas Islands has been settled by almost 200 years of possession, a victory in the 1982 conflict, and a 2013 public referendum vote by Falklanders. For Argentina, however, the United Kingdom’s right to fish and drill for oil just 300 miles off its coast — and 8,000 miles from Britain’s — still galls. Worse, British claims to the Falklands, South Georgia, and Sandwich islands shrink Argentina’s maritime economic zone by tens of thousands of square kilometers, which include oil and gas fields and valuable fish stocks. And those British island claims are the basis for its territorial claims in Antarctica, which overlap almost completely with those of Argentina and Chile.

Argentina’s claims to territory in Antarctica and surrounding waters. Image by the Argentine National Commission on the Outer Limits of the Continental Shelf.

In 2016, buoyed by a U.N. Commission ruling that backed its maritime exclusive economic zone claim, Buenos Aires reiterated its claim of rights to develop its piece of Antarctic territory, which would double Argentina’s land mass. In November 2020, the government released a new national map showing its bicontinental sovereignty. When the Antarctic Treaty comes up for renegotiation in the 2040s, those claims, as well as resource rights, will all be on the table. Buenos Aires may well bet that by 2040, Beijing could be just the superpower partner it needs to back its case against Britain. China, after all, sympathizes with grievances against territorial claims that are vestiges of a long-dead British Empire. For years, China has backed Argentina’s case against the United Kingdom at the G-77 summits of the United Nations.

China’s growing presence in Antarctica and its bending of the Antarctic Treaty rules away from conservation and toward resource exploration and extraction are well documented. Beijing wants more communications and logistics links to its scientific research stations, tourism providers, and fishers in the region. A Chinese operating location — a dedicated airport and port — in Tierra del Fuego would boost the local economy, improve local tourism and commercial services, and give China the strategic presence it seeks. If Beijing could secure terms similar to those of the space facility in Neuquén, this would essentially give its military a presence at the Strait of Magellan, a chokepoint in the transit route of U.S. aircraft carriers (too large for the Panama Canal) between the Atlantic and Pacific oceans, and easy access across Antarctica.

Illegal Fishing Puts Argentina in a Bind

But as is the case across Latin America, Argentina’s partnership with China is not without problems. Critics blame China for undermining Argentine manufacturing, promoting corruption, spreading COVID-19, and devastating Argentine squid stocks. All of South America was shocked by the summer 2020 spectacle of a mostly Chinese, 270-ship distant-water fishing fleet hoovering up millions of tons of fish just outside — and sometimes within —the Galapagos Marine Reserve, and then down the Peruvian and Chilean coastlines. In January, the bulk of that fleet, which uses transshipments and oceangoing suppliers to evade regulation, slipped through the Strait of Magellan into the South Atlantic, where Argentina has struggled for years to curb illegal fishing. Over the past decade, Argentina has had at least three dangerous altercations with Chinese trawlers. In one, a Chinese fishing vessel sank after it tried to ram an Argentine coast guard ship. Yet each year brings more Chinese fishers.

To help out, the U.S. Coast Guard sent to the region its most sophisticated cutter. Though initially welcomed by Argentina’s coast guard and navy, as the ship approached the Ministry of Foreign Affairs said the vessel could not dock. Recent Argentine governments have had complicated relations with their armed forces, particularly with the navy because of its role in the Dirty War of the 1980s. Still, the late decision was shocking, and it raises questions about Argentina’s willingness to work with the United States on issues of sensitivity to its new strategic partner.

With a Little Help from Its Friends

Luckily for the United States, it is not alone in its concern over China’s rising regional influence. Brazil is a leader in the South Atlantic and sees the South Atlantic as a realm of special interest and influence. Since the 1980s, it has championed the Zone of Peace and Cooperation agreement that declares the region off-limits to external state military posturing. Brazil’s impressive naval fleet, now including the aircraft carrier Atlântico and new Scorpene-class submarines — with a nuclear-powered sub on the horizon — is built to bolster that purpose, and trains regularly with South American and West African partners.

Brasilia would almost certainly object to the establishment of a Chinese base in South America, just as it would the establishment of a U.S. base, on the grounds of preserving regional security and sovereignty. Chile, Colombia, and other South American nations would likely agree, and with diplomatic and trade sanctions could present enormous costs to Buenos Aires. Stung by the uncertain future of its $50 billion investment in Venezuela’s oil sector, which is virtually defunct, Beijing may balk at tying itself too closely to another renegade partner.

To Fortify Partnerships, Be a Good Partner

The competition in this arena is only beginning, and the United States has historical, strategic, and cultural advantages over China in its American partnerships. Yet Argentina’s drift should serve as a wakeup call. Washington needs to show it has interests in the region beyond Venezuela and Cuba, immigrants, and drug traffickers. The United States should seek out opportunities, as China does, to meaningfully cooperate with South Americans on most serious problems. Greater regional cooperation with Covid-19 vaccines, for example, as China and Russia have done, would be a good start. Massive U.S. security assistance, directed mostly against drug trafficking networks, could be refocused on preventing gang membership and promoting safe neighborhoods, where the sharing of best practices could be enormously beneficial. The U.S. International Development Finance Corporation is a good start at presenting Latin American governments with options for non-Chinese infrastructure financing, but at present is way overmatched and unappealing when draped in U.S. conditions. Sending a Coast Guard cutter for a few weeks’ visit is largely symbolic. Washington could achieve more by assertively supporting global regulations on high-seas fishing, improved monitoring and reporting on distant-water fishing fleets, the creation of maritime reserve areas, and stronger inspection practices at ports worldwide.

The United States need not panic yet about China’s rising influence, but it does need to show up to compete, and with more than an occasional visit from a Coast Guard cutter.

Ralph Espach is a senior research scientist at the research and analysis organization CNA and leads the Latin America Strategy and Policy Portfolio. His books include The Strategic Dynamics of Latin American Trade and Latin America in the New International System.

Image: Prefectura Naval Argentina