The Modern Shetland Bus: The Lure of Covert Maritime Vessels for Great-Power Competition

The saboteur beached his small motorized launch in the darkness of an Arctic winter, climbing ashore through a frozen scree. In the distance, he could still make out the fishing boat that had brought him to the Norwegian coast as it headed into winter storms and rough seas, towards the safety of British waters hundreds of miles distant. If it overcame hazardous weather, treacherous currents, potential mechanical mishaps, and enemy patrols, the crew of fishermen could take credit for another successful delivery made by the “Shetland Bus.”

In the winter of 1940, the Special Operations Executive sent an Army officer, Maj. L.H. Mitchell, to the Shetland Islands off of Scotland’s east coast. His task was to organize an impromptu flow of Norwegian fishing vessels, which had agreed to make return trips to drop off saboteurs and equipment after evacuating refugees. The first operations under British auspices began in December 1940. In early 1941, Mitchell was joined by a Naval sublieutenant who spoke Norwegian, had spent holidays along the coast, and sailed small boats. David Howarth became the second-in-command of this covert fleet, called the Shetland Bus, and wrote the definitive history of the program. Howarth’s book is the largest single source for information on the campaign, and I rely upon it extensively in this article. In Howarth’s words, the bus line was designed as “a means for regular transport between Great Britain and Norway for sending messengers, leaders, instructors, trained radio operators and saboteurs, and cargoes of weapons.”

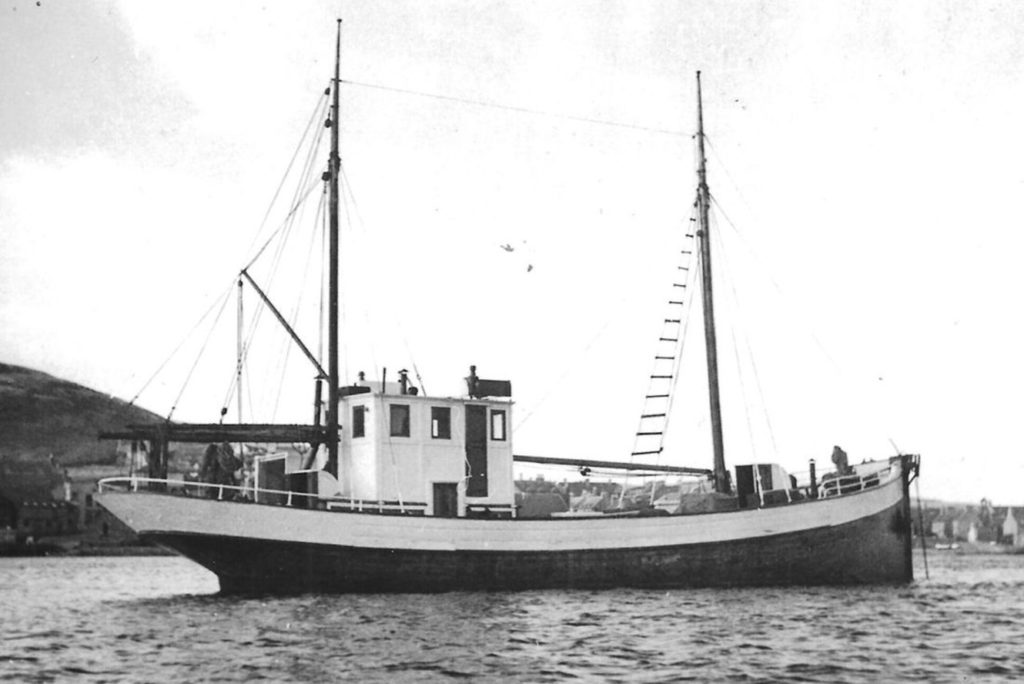

Between 1941 and -1945, the Shetland Bus vessels sailed over 90,000 miles, delivered more than 400 tons of arms and explosives, transported equipment to establish 60 covert radio transmitters, and smuggled refugees to England and agents to and from Norway. They used boats between 50 and 70 feet in length and 18 feet wide, which traveled up to eight knots. The organization totaled less than 100 men in the first years and never exceeded 150 men. The Shetland Bus boats were crewed by Norwegian sailors and supported by a staff of two British military officers, three British non-commissioned officers, three cooks, and a civilian cipherer.

The 2018 National Defense Strategy, directs conventional U.S. military and special operations forces to organize and prepare to counter near-peer competitors. While the threat is global, strategists recognize that the maritime environment, including global littorals, the “island chains” of the Pacific and Indian Ocean, the South China Sea, the Black Sea, the North Sea, and the Baltic coasts are all areas of expected conflict. Winning in these coastal areas and island chains will require a variety of tactics, methodologies, and specialized equipment. A modern Shetland Bus program would not address every contingency, but it would represent a Swiss Army knife-like tool that may provide flexibility and address several key needs.

The U.S. Marine Corps Commandant’s Planning Guidance issued in 2019 foresees the Corps’ primary role as being forward deployed “to compete against the malign activities of China, Russia, Iran, and their proxies.” A modern “bus” could supply marines deployed in the Expeditionary Advanced Base Operations concept of small units operating from remote islands. Marine Corps Commandant Gen. David Berger, recently stated that the Marines need to develop means to “move supplies, reposition forces, keep them sustained [with] affordable ships that are smaller, lower signature [in a contested environment].” Historically, in global war, there has been a need for small ships that can perform a variety of functions, from supply and logistics to close-to-shore raiding and reconnaissance. The Commandant’s Planning Guidance recommends development and procurement of ubiquitous “platforms that can economically host a dense array of lethal and non-lethal payloads,” which is exactly what Shetland Bus boats would be. Additionally, low profile civilian craft could support U.S. forces in the conduct of seaborne reconnaissance in future military operations. Finally, just as the Shetland Bus smuggled trained cadre to strengthen the Norwegian insurgency, Special Operations Command Europe has been developing a Resistance Operations Concept for the Baltics to fight invading Russian forces using local resistance elements, which could be supported by a modern Shetland Bus.

War in the Pacific is predicted to be quick and violent, as adversaries have learned not to allow the United States to build up forces. Thus, the United States would not have the same luxury that the British did in developing a program over time. For a modern “bus” to be useful, U.S. forces should develop the infrastructure now — by identifying vessels and possibly local crews. A new Shetland Bus would not need to rely solely on fishing vessels as the program did in World War II. Instead, a suite of various coastal and seagoing fishing trawlers, tugs, ferries, and other forms of shipping could help move units and supplies with a low profile and avoid the attention of adversary forces. Similarly, there may be situations in which these vessels would be operated by indigenous mariners, but they could also be crewed a hybrid mix of local seamen, allied naval elements, coast guard, harbor police, fishing monitors, security service personnel, and/or U.S. sailors, Marines, and operators. In some circumstances, the vessels may be entirely U.S.-operated with the vessel leased, purchased, or borrowed for specific missions.

U.S. units can begin making arrangements with liaison partners to requisition ships for wartime or establish purchase or leasing options with various civilian shippers. Working with regional partners, and even exercising the ships and crews, would provide opportunities to “train as you fight.” It would also develop capabilities, allow for the assessment of vessels and crews, and contribute to the development of doctrine for the use of a modern Shetland flotilla in the event of great-power conflict. Engaging with friendly forces to develop a Shetland Bus capability will also deepen existing relationships with maritime elements, which may be critical collaborators in a conflict. Some of these partners, such as Singaporean, Indonesian, Filipino, Japanese, and South Korean coastal maritime patrols, coast guards, fisheries protection units, and law enforcement entities, are not the first that come to mind as allies in great-power competition. Nevertheless, all have capabilities that may be uniquely valuable in a Pacific conflict, and similar elements in the Baltics and Scandinavia may be useful in countering an assertive Russia. Reviewing the history of the original Shetland Bus can help modern war planners better understand the benefits and limitations of such a program, and whether it offers any relevant insights for contemporary conflicts.

The Shetland Bus

Early in the war — with few allies — Britain chose to fight asymmetrically against the Wehrmacht that was then subjugating most of Western Europe. By late 1940, the organization that became the Special Operations Executive focused on use of the sea as a means to transport agents and supplies into Fortress Europe to conduct sabotage operations against the Axis powers. The Special Operations Executive units had some success developing sea lanes into occupied territory: For example, boats from Gibraltar carried supplies and commandos into France. Norway’s over 50,000-mile long coastline, however, was greater than the rest of Western Europe’s coasts combined, which afforded more opportunities for covert entry.

The Norway program used fishing boats and paid crews of civilian volunteers. The vessels were often outfitted with light machine guns and small arms. Some captains added armored plating and lined their wheelhouses with concrete to provide protection from air attacks. The British recognized that bad weather and darkness provided the fleet with the greatest protection from Nazi patrols. For this reason, the Shetland Bus operated primarily in the winter months — but often began as early as August and ran as late as May. Once in Norwegian waters, the boats used the inland waterway between the outlying islands and the mainland. The knowledgeable local seamen knew which fjords they could hide in, and which villagers might provide assistance.

A September 1941 delivery by the fishing boat Siglaos, was typical of the type of loads by the bus. On that trip, the crew delivered eight tons of cargo for sabotage operations, including high explosives with primers and detonators, various fuses, a large quantity of incendiary explosives, and hand grenades. It also conveyed weapons, including automatic pistols, knuckle dusters, rubber truncheons, and fighting knives. The Special Operations Executive engaged solely in subversion and sabotage, while the British Secret Intelligence Service conducted espionage and initially pursued its own maritime infiltration of Norway in 1941, but from 1942 to 1945, it relied upon the Shetland Bus.

Unique Missions

The majority of Shetland Bus operations ferried men and supplies, but it also carried out unique missions. One of the first was a specially modified ship, which laid several sticks of mines in the inland channel, though it later sunk in heavy seas. The bus played a minor role in the Allied effort to disable Nazi nuclear efforts. It provided an emergency medical evacuation for Knut Haugland, the ringleader of the attack on the Norsk Hydro heavy-water plant, which produced a critical ingredient for the nascent atomic bomb program.

One of the most daring raids attempted by the British was an attack against the Tirpitz — the sister ship to the Bismarck — hiding in a Norwegian fjord. The Royal Navy had to hold in reserve vital assets that could be used elsewhere, in case it broke out and threatened the British isles. The Shetland Bus team coordinated with the military to deliver two Chariots, an underwater delivery system designed to transport two divers to attach explosives to a ship’s hull. After a complex operation involving multiple faked documents (passes, crew rosters, registration papers, and an itinerary covering three months that had been stamped by harbor masters) and passage through German security, the vessel came within five miles of the Tirpitz, only to have the underwater cables towing the mini submarines break in swelling seas, requiring the crew to scuttle the ship and conduct a perilous escape.

Impact

World War II was the largest global conflict ever and evaluating the impact of individual operations and programs in light of the multiple currents and events that were occurring and impacting various theaters is nearly impossible. Ultimately, the decision to invade Russia or the loss of Stalingrad was likely more calamitous to German war efforts than any single Allied action taken against the Nazi war machine. That said, the Norwegian resistance — supported by the Special Operations Executive and the Shetland Bus — had an impact on Nazi forces in Scandinavia. By the end of the war, the Germans still maintained 10 divisions of troops, totaling 284,000 soldiers in the country who were tied down there rather than serving on other fronts. Clearly, for a relatively cheap investment, the Shetland Bus had an oversized impact in keeping the resistance alive and tying down Wehrmacht forces in Norway.

Modern Approach

The Shetland Bus model appears to be relevant for today’s U.S. military. Managing signatures is the critical vulnerability of expeditionary advanced base operations and distributed maritime operations. The U.S. military has been shifting its focus towards preparation for great-power competition against China and Russia, but at the same time, planners recognize that defense funding is expected to decrease and experts forecast a relative decline of U.S. power vis-a-vis both peer competitors — and thus, plentiful and inexpensive vessels will become even more valuable.

A modern bus would should by no means be considered the sole method for conducting maritime operations against adversaries. But at the same time, civilian fishing and other maritime vessels crewed by indigenous mariners could have great utility by hiding in the noise of the Pacific or European seas. A war against China is forecast to quickly accelerate and it is likely that the United States would have to absorb significant blows at the outset as China seeks to inflict significant casualties and destroy the U.S. public will to continue the fight. If these covert boats are going to be available in such a conflict, U.S. military units should consider establishing a program and attendant infrastructure now. The good news is that many units and organizations are already well-situated to identify vessels for such a modern bus, particularly by working with allied military and security services.

Operators of both the U.S. Joint Special Operations Command and the U.S. Special Operations Command are deployed around the world, frequently operating with foreign partners and often training surrogate forces. There have been increasing discussions about whether the Special Operations Command is properly oriented to address all of its core missions, after two decades of concentrated counter-terrorism efforts. Setting up Shetland Bus-style capabilities would align with those who argue that it is time for the command to refocus from a reactive contingency approach, and proactively develop capabilities which would support operators conducting unconventional warfare operations such as assisting resistance groups.

Operators in the U.S. Navy’s Naval Special Warfare Command work in maritime environments with friendly services and could leverage these connections to develop Shetland Bus infrastructure. One Special Warfare task force made up of Special Warfare Combatant-craft crewmen assisted the Kenyan navy to improve maritime security. They adopted a whole-of-government approach that expanded to include the wildlife service, coast guard, and maritime police. Similarly, small teams of naval operators cooperated with Filipino marines and SEALs across the Sulu Archipelago.

Like Naval Special Warfare units, the Marine Special Operations Command is designed to serve as a “connector” with U.S. military and civilian agencies, as well as host nation forces. A key role is organizing for war against a near-peer competitor, by developing infrastructure and preparing the battlefield. Marine Raider logisticians train to operate from expeditionary locations, and often rely upon locally obtained transportation and supplies, seek to utilize nontraditional sources of supply — including 21st-century foraging — and operate in austere environments. Like its sister services, the Corps has Marines with the requisite skills forward deployed partnering with local forces who could assist in developing modern bus capabilities.

What Would a Modern Shetland Bus Look Like?

With the growth of big data and the ubiquity of information provided by various intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance platforms operated by U.S. adversaries, readily identifiable U.S. military equipment will be sensed by the enemy. U.S. forces can avoid detection either through the use of vehicles with low signatures or, as U.S. wargamers learned to their detriment in the quarter of $1 billion Millennium Challenge exercise, by not conforming to expected methods of communication, tactics, or equipment. There is evidence that the Chinese recognize the value that commercial platforms provide for deception themselves, as the People’s Liberation Army Navy has recently test-fired rockets from a freighter’s deck.

The Japanese and Filipino fishing fleets provide examples of the number of small commercial fishing vessels plying the waters surrounding friendly Pacific nations. U.N. statistics listed 224,575 powered fishing vessels registered by the Japanese fishing industry in 2017. Vessels of less than ten tons make up 95 percent of this fleet. In 2017, the Philippines self-reported to the Regional Fisheries Policy Network that the country had 157,494 motorized vessels of three gross tons or less, and another 3,473 licensed vessels of greater than three tons. The United States would only need to make arrangements for a handful of these vessels to support Shetland Bus operations, and planners could add in a small number of various tender vessels, oil service boats, ferries, small container ships, tugs, and other specialized maritime watercraft that operate in the littorals, regional waters, and open ocean to provide an almost limitless menu of options. Cooperating today with foreign maritime elements not only enhances this capability but may deepen interoperability and improve alliances.

Winning over partners, particularly civilian crews, may require an information operations component to convince them to side with the United States against China in the Indo-Pacific region (or Russia in the North Sea). Paying competitive rates, particularly to use boats out of season, may attract locals and hearkens back to the original Shetland Bus operation in which the Norwegian fishermen earned a higher salary than their naval compatriots. Many fishermen and local seamen may already be predisposed to operate against the Chinese, given their aggressive efforts in the South China Sea and elsewhere. Some of the points of friction include the 2016 ruling by the Permanent Court of Arbitration that China violated the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea through its illegal claims of an exclusive zone in the Scarborough Shoal, fishing in the internationally recognized zones of other countries like Indonesia, massive fleets overfishing off the Galapagos Islands, and negative behavior, such as seizures of foreign fishermen or threatening military action against Vietnamese oil exploration. While adversaries may become aware of the U.S. program and efforts to develop Shetland Bus infrastructure through their spy networks, military attachés, and local supporters, this fact is not a deal-breaker. It may complicate their planning, introduce uncertainty, and require them to plan to counter it — causing them to expend significant resources in efforts to separate the wheat from the chaff, all of which impacts their ability to be nimble and counter U.S. and allied forces in wartime.

Ultimately, establishing a modern Shetland Bus-like capability provides many options for war planners. Perhaps a future U.S. force will approach a Pacific atoll or even a frozen Finnish fjord using techniques pioneered by Norwegian fishermen, who, during Arctic winters, channeled their Viking heritage fighting a clandestine war in the dark surf.

Christopher D. Booth is a career national security professional and served on active duty as a commissioned U.S. Army armor and cavalry officer. He has extensive experience abroad, including assignments in the Middle East, Asia, and Europe. He is a distinguished graduate of Command and Staff College-Marine Corps University. He graduated from Vanderbilt University Law School and received a B.A. from the College of William and Mary.

CORRECTION: An earlier version of this article incorrectly stated the length of Norway’s coastline at 775 miles. The correct value is over 50,000 miles.

Image: Scalloway Museum