Bringing the Army to Innovation

Will the U.S. Army be able to use cutting edge commercial technologies to dominate battlefields in the not-too-distant future? A company called Lumineye certainly hopes so. Lumineye (with which we have no affiliation) won the Army’s xTechSearch competition with a device that essentially enables soldiers to “see” through walls. Though Lumineye won the Army’s premier innovation pitch competition and offers game-changing technology, the Army has yet to transition the company’s solution into a widespread capability. In fact, after four iterations of xTechSearch less than half of the 43 finalists have gained pilot contracts, and far fewer participants have transitioned their technologies to the Army.

Although xTechSearch is only one component of the Army’s recent efforts to harvest commercial technologies for modernization, its struggles may indicate an Army-wide problem. Such problems could hamper the Army’s attempts to prepare for the future of war. A coherent assessment of the Army’s ability to adopt commercial technologies is therefore needed to determine whether the Army can meet its ambitious modernization goals.

We tackled this problem through Project Easy Button, an Army-sponsored pilot research program that we initiated at Stanford University. Our research, aimed at helping the Army more easily identify and acquire commercial technologies, involved 60 interviews with members of the Army innovation community and produced the first comprehensive map of the Army’s innovation ecosystem. Project Easy Button found three core insights: First, the Army has attracted significant new interest from the commercial sector. Second, doing business with the Army remains overly challenging for both commercial innovators and Army personnel. Third, growing company interest has yet to yield new capabilities. Without bold action, these problems will continue to afflict the Army’s efforts to bring innovative solutions to bear on the challenges of future warfare.

Maintaining the Edge

The Defense Department was once the world’s wellspring for technological innovation. For much of the Cold War, the department developed technologies that revolutionized military operations. U.S. defense contractors produced leading-edge defense products such as satellites, precision munitions, and stealth. Pentagon partnerships with industry and academia laid the groundwork for the modern internet, satellite navigation and GPS, and robotics and artificial intelligence.

Fast-forward nearly a half century and the department and its band of defense contractors have limited involvement in today’s most impactful innovations. The commercial sector leads key technology advancements such as AI, machine learning, autonomy, and cloud computing. These technologies are revolutionizing military operations and leaving the Pentagon behind. Commercial industry dominates six of the eight technologies identified in the 2018 National Defense Strategy as “changing the character of war.”

A Defense Department that does not lead technology innovation faces two related problems. First, the department can no longer safeguard access to game-changing defense technologies. Over the past two decades, China and Russia have accessed commercially available technologies at least as fast as the United States, narrowing the technological advantage the Defense Department has held since World War II.

Second, competition with near-peer powers will hinge on the ability of the department to transition commercial technologies into defense capabilities. Forces that are most capable of rapidly transitioning technologies will be best equipped to fight. China, for example, has implemented an aggressive technology transition plan through its Military-Civil Fusion strategy. The United States has yet to build comparable regular, sustainable, and measurable pathways for transitions.

An Army Committed to Innovation

In the halcyon days when the Pentagon led innovation, a diverse range of private companies clamored for defense contracts. Today, the Pentagon acknowledges that exploiting defense-relevant commercial technologies requires the department to seek commercial innovators through new programs and organizations (e.g., Defense Innovation Unit). Additionally, each service has established its own unique touchpoints to engage with non-traditional companies (e.g., AFWERX, Army Applications Laboratory, NavalX).

Of the other services, the Army’s strategy stands apart. Guided by acquisition chief Bruce Jette, the Army has taken a deliberate, top-down organizational approach to modernization. Jette has reshuffled Army research, acquisition, and sustainment entities into a construct known as the Future Force Modernization Enterprise in order to quickly identify, acquire, and field new capabilities. The Army has established Army Futures Command, the first new four-star command in over 40 years, as the central node for driving modernization efforts. In addition, Jette views commercial innovation as being “critical to the Army’s future” and consequently established the Army Applications Laboratory and the xTechSearch competition to specifically engage companies that don’t typically work with the Defense Department, or non-traditional companies.

Despite all this apparent progress, it is unclear whether today’s Army is better suited to transition commercial technologies into warfighting capabilities. There has been little discussion around the effectiveness of the Army’s approach to modernization. Some have gotten close. Steve Blank, Garrett Custons, and Jason Rathje have tackled broad innovation problems afflicting the Pentagon, but did not specifically assess Army modernization. A 2019 Government Accountability Office report assessed issues with the formation of Army Futures Command but did not evaluate the Army’s overall ability to adopt commercial technology and build sustainable partnerships with industry. Peter Khooshabeh and Christopher Zember discussed the strategic value of Army partnerships but did not assess the outputs of those partnerships.

Given the loss of comparative advantage with rivals and the amount of resources invested to date, it is critical to examine the Army’s progress. Such an analysis is foundational to understanding whether the Army is on track to meet its modernization goals, and whether it can keep pace with the rapid technological changes of near-peer adversaries.

The Current State of Army Innovation

To address this problem, Project Easy Button assessed the Army’s efforts toward identifying, acquiring, and fielding capabilities from non-traditional companies. To do so, we mapped and critiqued the Army innovation ecosystem and conducted 60 interviews with various Army personnel and non-traditional companies engaged in modernization efforts. The research reveals both successes and shortfalls in the Army’s approach. These are described below.

The Army has Generated Massive Interest Among Non-Traditional Companies

Army programs designed to attract non-traditional companies have been met with enthusiasm. According to a senior official, Army Applications Laboratory received 5,500 inquiries in 2020 from commercial firms. xTechSearch has worked with over a thousand companies in roughly two years, 60 percent of which had previously never worked with the government, exposing the Army to technologies it would not have otherwise seen. In addition, the Army’s Industry Opportunities Brochure has been the most downloaded document on the Army’s website for the past 1.5 years, proving valuable to Army personnel and companies alike. Therefore, and despite popular perceptions that commercial technology firms do not want to work with the Pentagon, thousands of companies are eager to collaborate with the Army.

This is no small achievement.

The Army owes its success to lowering the barriers companies face in entering the Army marketplace. Lower barriers mean greater company interest, which in turn means broader exposure to the commercial solutions needed to compete against the likes of Russia and China.

Doing Business with the Army Remains Challenging

The Army has attracted companies with the allure of easily entering a lucrative new market vertical. The reality is somewhat different. Nearly every company interviewed found business development with the Army to be more difficult than it imagined. Companies pointed to two salient challenges: identifying relevant Army opportunities and engaging with potential Army customers.

Companies struggle with the wide array of disparate platforms the Army uses to advertise opportunities (e.g., grants.gov, BetaSAM, SPARTN, Vulcan, Office of Small Business Programs). Firms miss pertinent opportunities because they are unaware of which platform to use, or fail to successfully leverage these sites because of non-user-friendly interfaces. To illustrate, a battery technology company could find solicitations related to new power sources on at least seven different Army websites. The company would need to properly filter over 300 Army search results on BetaSAM for a term like “wearable battery” to understand relevance and eligibility.

Companies also face obstacles engaging with potential customers within the 1.2 million-person Army bureaucracy. It can take weeks to parse through countless organizations to identify stakeholders who could benefit from a potential technology. At that point, firms must separate actual customers from those who deal with oversight and requirements generation or lack purchase authority. Companies struggle because they lack requisite knowledge of the Army’s bureaucracy and hierarchy to make the right connections.

Failure to identify opportunities and connect with customers frustrates companies and leaves them feeling unsupported. For many of these firms, feelings of abandonment led to frustration and ultimately to quitting the Army marketplace.

Army Personnel are Struggling to Convert Interest into Capabilities

The high volume of inbound inquiries from commercial companies has yet to result in an influx of new capabilities. Army Applications Laboratory, for instance, conducts an average of 106 engagements a week with industry. Yet, many of these interactions stall after initial conversations or fail to progress to pilot programs. Transitioning from initial on-ramps to more substantive Army contracts is also an issue. Despite being the Army’s most visible innovation competition, xTechSearch has primarily facilitated access to prototyping contracts on the scale of a few hundred thousand dollars. These insights are consistent with the Army’s historical underperformance in transitioning technologies in its Small Business Innovation Research program.

There are many reasons behind the Army’s struggle to transition technologies. Nearly all are rooted in an antiquated Army acquisition process that was designed to slowly purchase small numbers of highly complex systems rather than rapidly acquire technologies from nimble non-traditional companies. A key symptom of this underlying problem is the heavy burden placed on Army personnel to support companies in a seemingly inhospitable landscape. Army officials repeatedly stated that it fell to them to guide companies past a host of challenges related to identifying funding, contracts, and customers.

Army personnel working with companies face significant demands on their time because of the high volume of inquiries. While these individuals are often highly motivated to help, they simply lack the bandwidth to connect every interesting tech company with Army customers. Army organizations and companies do not appreciate that Army personnel must go through the same time-consuming process of navigating the bureaucracy as any private company. There are no shortcuts.

As a consequence, Army personnel are limited in the number of companies they can support. Unsupported companies tend to either redouble their outreach efforts, further tapping Army personnel bandwidth, or get frustrated and quit. Neither outcome is good for the Army.

In summary, while the Army’s success in attracting new interest from the commercial sector is laudable, the Army does not appear to be at the point of rapidly acquiring and fielding commercial technologies at scale. Non-traditional companies and Army personnel continue to experience friction in transitioning commercial technologies into defense capabilities. Companies cannot identify opportunities and customers. Army personnel lack the time to give companies the support they need.

Unlocking the Army’s Arsenal of Opportunity

In the pursuit of bringing itself to innovation, the Army has heavily focused on attracting new technology companies through efforts such as pitch competitions and innovation days. However, the Project Easy Button findings indicate that building deeper connectivity between Army personnel and companies is a vital part of the technology transition process. Companies and Army personnel are unable to quickly identify potential areas for collaboration because information on Army opportunities and projects resides on disparate platforms and with people unknown to companies and their supporters.

The status quo has dangerous implications. As frustrations mount, companies could ultimately leave the Army, or be deterred from collaborating in the future. Such an exodus would negate the success the Army has had to date in attracting industry interest and ultimately starve the Army of the very technologies it needs to modernize and compete with near-peer rivals.

Truly reconfiguring the Army to quickly transition commercial technology will likely take years. The Army will need to change mindsets and acquisition procedures and reallocate funding. In the medium term, the Army will need to funnel more resources to touchpoints like Army Applications Laboratory, Small Business Offices, and xTechSearch to provide better support. Yet these solutions also require time to implement, and the Army needs quick wins to sustain commercial interest.

In the immediate future, the Army can focus on resolving issues linked to transparency and awareness by improving data flows to Army personnel and companies. One solution in particular could immediately serve these purposes while also buying time to implement more complex changes.

Companies and Army personnel both need improved access to data so that they can more easily source opportunities to collaborate. A two-sided opportunity filter could address the concerns of both industry and Army personnel by consolidating information on opportunities and potential customers. Such a platform could increase Army-company connectivity and improve technology transitions by building off the Army’s success with the Industry Opportunities Brochure.

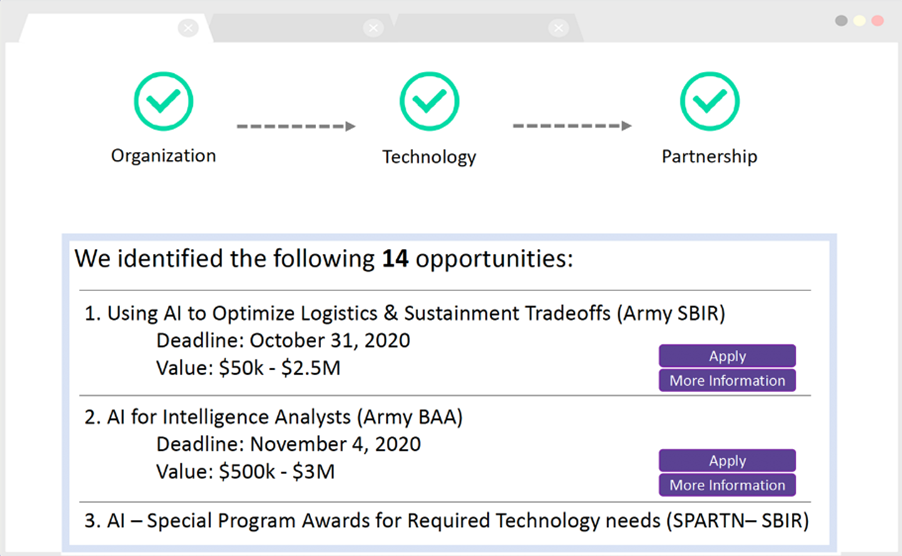

Companies could use such a filter to conduct targeted searches based on their technology sector, company maturity, and technology maturity/Technology Readiness Level, as well as goals in engaging with the Army (e.g., pilots, prototype funding, production contracts). The search output (mocked up below) could consolidate information currently housed across numerous Army sites to display relevant opportunities, information about the program and organizations involved, and similar ongoing Army efforts on a single resource page with links to apply.

Such a solution could empower industry to more effectively conduct business development within the Army. Companies would no longer need to rely on navigating multiple platforms and informal networks to source customers and opportunities. The filter could also lessen the burden on Army personnel at touchpoints such as Army Applications Laboratory and the Office of Small Business Programs by reducing the number of irrelevant commercial inquiries while increasing their ability to identify relevant companies and acquire and then field technologies. Moreover, Army personnel could gain greater awareness around ongoing Army projects. Such information could be valuable to identifying potential areas of collaboration, as well as expediting connections between companies and relevant Army stakeholders. Greater transparency and awareness for Army personnel and companies would yield the connectivity necessary to increase the rate of technology transitions.

Moving from Interest to Partnership

The Army has made significant progress with outreach to commercial industry in a relatively short time. Prevailing in future conflicts, however, will require successfully converting that interest into warfighting capabilities. While this undertaking will require persistent effort for years to come, the Army is not alone in this journey, as the rest of the Pentagon faces similar challenges.

It is clear that the Army needs to move beyond simply attracting industry interest to creating more productive partnerships with commercial companies. A first step would be to bring the Army closer to innovators by providing the tools necessary to increase transparency and access for Army personnel and companies. The step would lay the groundwork for transferring the technologies truly needed to field a competitive force. Such an achievement would be recognized from Austin and Washington to Beijing and Moscow.

Jeff Decker, PhD, is program director of the Hacking for Defense Project at Stanford University is a co-instructor of the Hacking for Defense class. He is an Army Second Ranger Battalion veteran.

Mrinal Menon is a researcher and M.B.A. candidate at the Stanford Graduate School of Business. He has held growth, strategy, and business development roles at multiple defense-focused start-ups. He is a U.S. Navy veteran and former surface warfare officer.

Image: Public Domain