Remembering When the Memories Are No Longer Our Own

In Afghanistan, my platoon drew pawns on all our gear. Pawns, as in the chess pieces. Or we’d write the word “pawn” across the knuckles of our Nomex gloves, the ones that wouldn’t melt if the heat wave from an improvised explosive device swept over our bodies. A few guys got pawn tattoos when we got back. There is an old saying in the Marine Corps: “It does what it’s told.” We did what we were told. We knew we were just small pieces in the great American war machine.

My platoon and I had sacrificed some of our autonomy and agency in our decision to join the military. The policymakers kept the war going, the bigwigs decided our unit was up in the rotation, and our superiors gave us our orders when we arrived in country. There isn’t much room for individualism when you are a Marine infantryman.

I may have felt like a pawn in Afghanistan. But my individual freedom wasn’t the only right I sacrificed when I joined the Marine Corps. On Veterans Day, a day for collective remembering, veterans also lose the right to memories of our own.

This Nov. 11, Americans will gather — virtually, in most cases — to remember and thank the country’s veterans. Veterans will sit, sometimes with masks, at restaurants offering free meals. There will be profiles in local news outlets of aging veterans. Red, white, and blue bunting will be draped over main streets in small towns across the country. Americans will thank veterans for their service, and their sacrifices.

There are many other days in the year when the country thanks its military. Sometimes I fear there are too many such occasions. Veterans often serve as a kind of stand-in for patriotic values that many Americans feel disconnected from — service, selfless sacrifice, unity, action toward a common goal. The mythos of the non-politicized military allows the veterans to occupy a vanishing space, one that is seen as largely untouched by increasingly partisan politics. As a result, veterans have taken on a kind of talismanic status. Fighter jet flyovers and half-time shows featuring those in uniform serve as much to sanitize the experience of war as they do to connect veterans with the civilian population they served.

Yet, in a culture awash in military symbolism, Veterans Day still holds a cultural prominence, and still holds a touch of the sobriety stemming from the day’s origin — Armistice Day, a day to be thankful for the end of war and be mindful of the horror war inflicts on those who wage it.

Individual Experience, Collective Memory

As the country celebrates its American values, its history, and its veterans, it curates a specific kind of cultural memory. This takes veterans’ memories of war and weaves them into a larger national tapestry — but in that act, it also robs veterans of their right to their lived experience of military service. Too often lost in collective recollections are the terror of mortars dropping, the smell of flesh burning after a vehicle explosion, or the sheer joy of a vehicle driven high speed down a hill in the middle of a war zone. Veterans Day can be a day to rectify that.

Veterans Day can be a day to overcome other hurdles to remembering as well: As we grow older, memories fade. Platforms that focus on war stories are disappearing. Americans have a short attention span, and the nation’s capacity for attention in Iraq and Afghanistan is strained. And the pandemic has isolated Americans and made remembering difficult.

In war, the forces of violence rob those affected by war of their individual autonomy. The pressure of collective memory continues to rob the victims of war of the memory of their individual experience.

Facing all these challenges, how do we remember, on this day, war?

How can a lance corporal break free, even just for a moment, of all the violence and bureaucracy in war? How can veterans keep their memories alive, in the wash of collective narratives about service?

What do I do on Veterans Day? I remember Jackson, and I eat cake.

Remembering Jackson

The diesel engine of our clunky, green light armored vehicle revved up, as it raced downhill. The driver was a blonde kid named Jackson from southern Illinois who had played a little college baseball. He was speeding up to hit the big pool of water that swamped the road in the last stretch on the way back to the outpost. If he hit it fast enough, he’d spray me and Chuck, Hess, and Sgt. Lap— all of us with our heads popped out of the vehicle hatches — with ugly brown ground water. Lap, the vehicle commander, had stuck his feet through the small passage between the vehicle commander’s seat into the driver’s compartment and was kicking the back of Jackson’s head trying to get him to slow down. But Jackson got his and we all got wet, and laughed and howled and felt happy and childish and free.

As I get older, my memories of war are fading. It’s been nearly a decade since I came home. My mind reaches out to try and remember a patrol on a given day, or the name of that guy in another platoon, but more and more often the name escapes me, or the patrols run together in my mind, replaced by dinners with my family, dates that I’ve been on, college class lectures, or nights on the couch watching Netflix.

That memory of the vehicle and the pond, though, I’ve kept. A moment when Jackson broke free from the crushing pressures and fear and danger of war, just for a moment. That memory belongs to all of us, even Jackson, who we all gathered to lay to rest a few months ago after he took his own life. We buried him under the maple and magnolia trees on a hill in southern Illinois.

Source: The author and his former platoon gathered in May 2020 for the funeral of Derrick “Gage” Jackson.

After Jackson’s funeral, we all gathered together in the lobby of the motel where we were staying. I went to the small-town gas station in my black suit to buy a couple 12-packs of beer. Some correction officers were there in uniform. They had worked with Jackson after he got out. They asked if we were marines. We told them we were. They bought us a couple of airplane shots, the kind in little plastic bottles behind the counter, and told us thanks for coming.

Back at the motel, we told stories, like the time when Jackson hopped in the turret of a parked light armored vehicle to provide fire support for a squad on patrol that had come under fire and had gotten kicked out by a more senior marine. We shared old gripes like about the sergeant we all hated, or the time we’d gotten caught on a four-day-long foot patrol with no water and had to wait for a helicopter resupply that couldn’t come because there was a dust storm. I hadn’t seen many of these guys in years. I felt safe around them. One by one, we had to leave to catch flights or start long drives. Back home, I couldn’t talk like we did that night. I’d found community, and a space to remember safely, but it was fleeting. I wondered when we’d see each other again.

Memory and Society

Veterans Day is a day for remembering. In the United States, state violence is still utilized as a central tool for achieving policy goals. Yet, it’s a culture that is increasingly distant from the realities and costs of war. Drone strikes and special forces raids keep the violence that is committed in the name of U.S. citizens at a distant remove, while a low troop footprint keeps casualties below a threshold that would draw a public outcry.

The country fetishizes the military aesthetic — dressing in MultiCam and combat boots, and celebrating the awesome and terrible level of precision with which the U.S. military can inflict violence — while remaining largely insulated from the effects and costs of that violence. Veterans, however, are a living reminder of war, the keepers of war’s memories. By retelling those stories over beers in the motel, we kept the memory of our friend alive, but also the memory of the war we fought together.

Desperate for a reprieve from tribalism, Americans have turned toward the military as an icon of shared American values. There is no small irony then, that many among those who do serve identify as their own kind of tribe, separate from those they protect. The sheer number of days and events thanking the military can become overwhelming and hard to track.

There is a tension in the country’s celebrations today. In some ways, Veterans Day strips away some of the civic burden and pageantry placed on military members and veterans, and returns Americans to core truths about the veteran experience, centered on war and violence. The brutality and industrialized violence of World War I are potent foils for a collective memory that too often sees war as a struggle between principles like good and evil, or liberty and tyranny, and does not recall the visceral details of conflict — the families ripped apart, the blood spilled, the bones shattered, and the rain of steel upon human flesh, or uprooting earth, punching holes in lungs, and tearing chunks of arms, legs, faces, and eyes.

On the other hand, in a quest to heroize veterans, society overlays its own values on their stories. Collective memory is curated. As collective creatures, we cannot help but impose hindsight onto collective memories of the past, nor can we avoid imposing values and sentiment onto raw experience.

When Americans remember 9/11 today, they remember something more attenuated and distant than the actual event. Their memories are the result of a cultural production. On 9/11, the country remembers sadness — for the lives lost and the futile wars that were launched in the aftermath of the terrorist attacks on New York and Washington, D.C. — more than fear.

When Americans remember World War II veterans, their hearts swell with pride for the Greatest Generation. I wonder if the veterans of that war would have wanted that moniker. I wonder if the collective memory of World War II as a triumph of liberty over tyranny does more for those now living who did not fight in the war than it does for the few remaining surviving veterans.

There are other tensions as well. Time and space also make remembering harder. My friends from my time in service are older now, all in their 30s and 40s. We are flung across the country, from California, to Nebraska, to New York. We have jobs, student loans, mortgages, families, children, and lives outside of our time in service. Every day we move further away from those years we shared together in uniform. Memories fade, bellies grow fatter, and old concerns are replaced by new ones.

This year has been particularly hard. The pandemic has made us more physically isolated than ever. Memory is a collective action, something done together, in motel lobbies, over beers, or at the bar on the Marine Corps’ birthday, or in yearly reunions with the members of an old unit. When we gather, stories get twisted, corrected, retold, hashed out, exaggerated, swapped, and shared. “Do this in remembrance of me, he said. Remember me in the breaking of bread.” But coronavirus has taken that from us. We’ve been locked up in our houses or behind masks for months, and there has been precious little bread breaking or beer drinking together in these last few months.

The spaces in which to remember are fading too. Dave Dillege, the founder of Small Wars Journal, passed away in May. The New York Times’ “At War” section is being shuttered. Tom Ricks closed up his “Long March” column at Task and Purpose in 2019. War on the Rock’s “Bombshell” podcast is wrapping up. As the U.S. military presence in Iraq and Afghanistan has dwindled, so too have the media spaces that sprang up to cover them. The great war blogs of the early years of the Iraq War are now faint memories. There are fewer and fewer new, first-hand accounts of war from American service members. Although war continues to affect the people of Iraq, Afghanistan, and many other countries as well — 21 students were killed in an attack on a university in Kabul on November 1, for example — it affects U.S. citizens less and less. The collective attention Americans pay to their wars is quickly disappearing.

Eating Cake

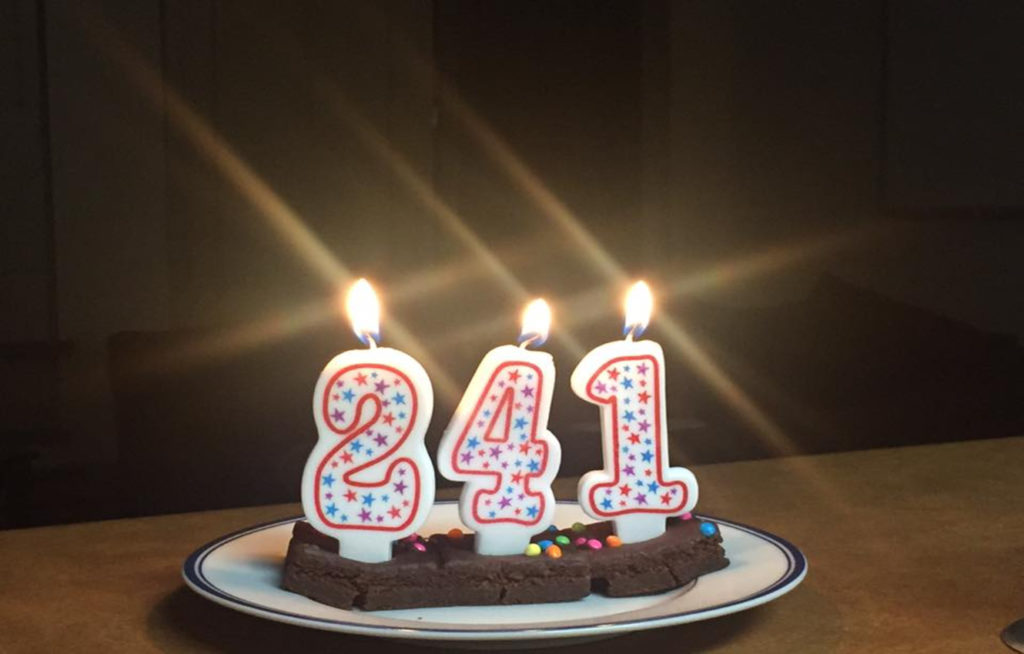

On the Marine Corps’ birthday, the day before Veterans Day, marines always gather together and eat cake. One year, my unit had the birthday ball at a casino and the cake was a fancy three-tiered monstrosity. In Afghanistan, we ate a shelf-stable group ration cake. Wherever marines find themselves, they always eat cake.

After I got out, I lived with another Marine vet in Montana. On the Marine Corps’ birthday, we put candles into a cosmic brownie. We felt alone, all the way out there away from our families, with the cold Montana winter laying ahead of us. After our little ceremony, we went out to the bars in downtown Bozeman for a drink. In no time we found lots of other Marine vets out celebrating. They weren’t hard to spot. Just look for the guy ordering shots of Jameson at the bar, chances are he’s a marine. We did shots and told stories and celebrated together with the community we found that night. On the Uber ride back to our apartment, I felt good. I felt safe.

It is tradition for the oldest marine present to eat the first piece of cake and for the youngest marine to eat the second. It’s a symbol of tradition being passed on — of how we keep our shared memories and heritage alive. We gather together, young and old, and remember together.

Veterans Day is a day for remembering. Remembering the “Forever War” is hard. In almost 20 years of war, nearly every month holds some place in the collective narrative. There is hardly a day of the year that goes by that I don’t see a post commemorating a servicemember who died on that day or a major event in the war. The sheer size of the history, the number of events, the breadth of it all makes the process of keeping the memory of that war alive a daunting task. The pressures of the collective memory, the passage of time, a pandemic, and lack of space make the task of remembering even harder. But no matter how hard it gets, at least there is cake.

Peter Lucier is a Marine veteran. He is currently a law student at Saint Louis University.

Image: Photo by author.