What If Sherman Kent Was Wrong? Revisiting the Intelligence Debate of 1949

There’s little the United States intelligence community holds more sacred than the teachings of Sherman Kent. Widely considered the “father” of American intelligence, his stamp upon the profession is indelible. His name is practically synonymous with both the craft of analysis and the standard model of intelligence-policy relations. His book Strategic Intelligence for American World Policy remains “the text by which succeeding generations of fledgling analysts [are] schooled, a book that studs the footnotes of those that followed.”

But what if he was wrong?

What if the assumptions Kent’s model of intelligence was built upon are no longer sound? What if his emphasis on academic objectivity has done more to diminish the influence of intelligence than to enhance it? What if his positivist view of the world, in which effect follows cause and the future can be reasonably forecasted, is mistaken? What if his solution to inevitable intelligence failure — more collection — has left the intelligence community struggling to keep its head above water in a veritable ocean of data?

Nothing lasts forever, and models that were once sound can become harmful when conditions change. Kent’s approach, which left intelligence officers artificially removed from the policymaking process in a quixotic quest for perfect objectivity, has failed in an era of abundant information. We are living through a period of disruptive change that is fundamentally altering the global landscape, contravening conventional wisdom, and eroding the very foundations of once-stalwart institutions — and that’s according to the very National Intelligence Council whose forerunner Kent created.

Under these conditions, intelligence practitioners owe it to future generations to put inherited wisdom to the test — to pose questions with a hammer, as Nietzsche put it, so we can find out if our idols ring hollow.

The Intelligence Debate of 1949 Revisited

Sherman Kent and his contemporaries answered President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s call to service in World War II as the “carefully selected, trained minds” needed to staff the new Office of Strategic Services. Drawn from the lecture halls of the Ivy League, they created the new field of strategic intelligence on the fly and under wartime conditions.

When the guns finally fell silent on Aug. 15, 1945, it was clear that the postwar world was going to be very different from the prewar one. American policymakers were beginning to realize the United States needed a permanent strategic intelligence function. Stalin had drawn an Iron Curtain across Europe, and the shadow of atomic war began to eclipse other concerns. “The whole world of the future hangs on a proper judgment,” as Secretary of State George C. Marshall put it.

But while the need for a postwar intelligence function was clear, there was no agreement on its organization, placement in government, or even its basic functions. The ensuing “intelligence debate” was just that — an argument about what the role of intelligence in a democracy should be and how any new agency would go about playing it. There were many voices in this debate — notably George S. Pettee, William Langer, and Roger Hilsman — but in the end, it was defined by just two: those of Sherman Kent and Willmoore Kendall.

Sherman Kent’s model drew a strict separation between the functions of intelligence and policy, between the thinkers and the doers, as Kent himself put it. And if that sounds elitist, well, that was Sherman Kent for you.

The blue-blooded scion of a prominent West Coast family and a Yale historian, Kent’s heroes were journalists like Walter Lippman and historians like himself. His ideal intelligence officers, described in his book, were to be like Plato’s philosopher-kings — a coterie of elite, self-policing advisors who would stand at the policymaker’s shoulder “with the book opened at the right page, to call their attention to the stubborn fact that they may be neglecting.”

Kent was adamant that “intelligence is not the formulator of objectives; it is not the drafter of policy; it is not the maker of plans.” But in the very next passage, he wrote that intelligence “cannot serve if it does not know the doers’ minds; it cannot serve if it has not their confidence.” To be at once close and distant, to know the doers’ minds without influencing their plans — sounds more like Zen kōans than practical policies. It is not surprising that intelligence agencies have struggled under Kent’s model to find the right balance.

Kendall could not have been more different. He was a precocious autodidact from a poor Midwestern family who enrolled at the University of Oklahoma at age 14. He spent his later youth as a Trotskyist roaming Spain during its Civil War, before abandoning these youthful flirtations and becoming a staunchly conservative public intellectual. Though he, too, ended up on the faculty at Yale for a particularly contentious 14 years, he never considered himself “one of them” and was in fact paid to leave.

Kendall spared Kent none of his savagely condescending wit in his short, sharp review of Strategic Intelligence. Kendall pointedly criticized what he viewed as Kent’s Ivy League elitism and tacit blessing of the status quo. He blasted what he saw as Kent’s apparent willingness to cater to the preferences of the “doers” despite all his talk of objectivity and independence. Strategic Intelligence was “not the book of a reformer who takes pen in hand to expose and remedy a bad situation,” he wrote.

Kendall also took aim at Kent’s decidedly reductivist worldview, which was founded on repurposing “the classical method of the natural sciences,” as Kent put it, “to serve the far less exact disciplines of human activity.” Kent’s method of intelligence production was to gather all the available facts and then use them to make estimates about a given situation. This “crassly empirical conception of the research process,” Kendall wrote, was marked by a “compulsive preoccupation with prediction.”

Kent likely bristled at these accusations, but Kendall wasn’t far off. Kent did believe, writing in 1964, that “within certain limits,” the collection of more “facts” made it not so difficult to “estimate how the other man will probably behave.” The thing is, we now know that Kent was wrong about that much at least. More information is useful to a point, but beyond that point, more becomes confounding rather than enlightening — a fact that should give us pause in our information-inundated world.

For an example of the very real limits of Kent’s approach, recall perhaps his greatest failure. In September 1962, the Office of National Estimates at the CIA that Kent led published its judgment that it was “highly unlikely” the Soviet Union would place offensive ballistic missiles in Cuba. The assessment was based on what the office’s analysts could see through intelligence collection, and amplified by their assumption that placing such weapons in Cuba would “be incompatible with Soviet practice,” as Kent put it.

In normal times, that might have been right. But crises emerge from the exception, not the rule. And the Cuban Missile Crisis was a big exception, one that brought the world within a hair’s breadth of Armageddon.

Soviet premier Nikita Khrushchev’s principal concern was America’s overwhelming first-strike capability — a destabilizing advantage that President John F. Kennedy had just exacerbated by placing Jupiter medium-range ballistic missiles in Turkey, a provocation Khrushchev called “intolerable.” The Soviet leader believed placing his own missiles in Cuba was a proportionate response that would give Americans “a little of their own medicine” and restore some sense of strategic balance.

But Khrushchev had misjudged Kennedy, and Kent misjudged Khrushchev. His team simply lacked the creativity to entertain the notion that the first secretary might gamble so boldly in response to what he saw as American overreach. They also were not aware of that very overreach precisely because they were so independent of the policymaking process. When incontrovertible photographic evidence of Soviet missiles became available in October, Kent had to admit they had got it wrong.

That didn’t stop him from defending his team’s assessment, though, and he could be just as condescending as Kendall. He argued that his team had made the right call based on available information and that they could not be held responsible for Khrushchev’s “incredible wrongness” in acting against the Soviet Union’s track record, and indeed, against what Kent saw as their best interest. He was even more confident in his approach. For better or worse, he wrote, “This is our method; we are stuck with it, unless we choose to forsake it for the ‘programmer’ and his computer or go back to the medicine man and his mystical communion with the All-Wise.” There was little credence given to creativity in Kent’s world. In response to a later criticism of his preference for percentages to express the likelihood of events, he quipped, “I’d rather be a bookie than a god-damned poet.”

Had Kendall been aware of these deliberations (they were highly classified at the time), he might have cited them as proof of his earlier critiques. He had written that while Kent’s conception of intelligence might work for simple cases of “absolute prediction,” it was unsuited for what he called “contingent prediction” — that is, cases where the outcome was dependent on the interaction of multiple independent variables. The challenge in Kent’s empiricist worldview, according to Kendall, was to find better ways to process “a tidal wave of documents.” Kent acknowledged as much, writing that there was already “so large a volume of data that no single person can read, evaluate, and mentally file it all.”

Kendall’s biggest issue with Sherman Kent, though, was his view that Kent lacked a sense for what he called “the big job,” the “carving out of the United States’ destiny in the world.” He accused Kent of seeing the world “not as a system to be influenced” but “as a tape all printed up inside a machine, the job of intelligence to tell the planners how it reads.” The challenge, he wrote, shouldn’t have been to reduce intelligence officers to trumped-up file clerks — it instead should have been to enable them to “work under conditions calculated to encourage thought.”

The truth is that the standard model — in which reticent intelligence officers kept themselves separated from policy, collecting data and making forecasts — was flawed from the start. It fundamentally misunderstands both how policy gets made and, more crucially, human nature. In Kent’s orthodoxy, intelligence officers who are cloistered from the messy and often emotional process of crafting policy nonetheless present “judgments” to the benighted “doers,” as if from on high. This framework sets up an adversarial relationship from the outset, one that has too often left intelligence officers dismissed as academics with no skin in the game, hypercritical naysayers, or more recently, the rogue agents of a “deep state.”

These problems were recognized early on. One of Kent’s contemporaries noted in 1962 that most policy decisions were made without any input from intelligence — something Kent himself begrudgingly acknowledged and that has since been confirmed again, again, and again. Even when policymakers do make use of intelligence, it is often only insofar as it supports their preordained conclusions, a pathology evinced on both sides of the political aisle. There is no evidence to support the naïve assumption that policymakers will change their minds when presented with one of Kent’s “stubborn facts.”

It Is Time for a New Intelligence Debate

Sherman Kent won the debate over how intelligence would be conducted in postwar America, and there is no denying his foundational contribution to the craft. He made it his life’s work to help that craft mature into a distinctive profession. But Kent himself would have been the first to agree that keeping the profession healthy requires “a constant assessment of needs,” and “lobbying for vital changes.” If intelligence is to retain its significance in the 21st century, that is exactly what intelligence practitioners must do.

Intelligence is instrumental. It does not, as Kent wrote, “pursue knowledge for its own sake.” Its purpose is “using information for good,” as former Principal Deputy Director of National Intelligence Sue Gordon says. And though much has changed since Sherman Kent’s day, one thing that has not is the need for independent, insightful assessments of national security issues that — and this is critical — can be put to good use.

Intelligence analysis in particular has come a long way since Kent and his contemporaries invented it. There have been significant reforms to both analytic tradecraft and argumentation — most recently with the mandate for officers to make their reasoning and evidence explicit by using structured techniques. These reforms, however, have all made only incremental improvements, and all squarely within Sherman Kent’s standard model. They have arguably made analysis better but have done little to bridge the gap between intelligence and policy that keeps so much of it from being put to use.

If institutions hope to make intelligence more useful, they must eschew the noble lie implicit in the standard model and come to terms with the fact that intelligence has always been as much a social and political activity as a technical or cognitive one. This will require a shift in their conception of intelligence itself. Instead of seeing intelligence as a mere product used by decision-makers, they should view intelligence officers themselves as the product — trustworthy professionals, experts at problem-framing and decision facilitation, whose service is expanding a user’s mental map of the world and helping the user to navigate it more easily.

Can intelligence officers do that without abandoning their values — the courage to speak truth to power and the integrity to eschew political bias?

Of course they can. Political does not mean partisan, and objectivity is not the same thing as neutrality. Intelligence officers are at least as professional and dedicated as the millions of doctors and lawyers who work closely with their clients every day and are not afraid to give them news they do not want to hear.

Concerns about the politicization of intelligence are warranted, and we must always guard against it — but there is little evidence politicization occurs in the way most of us think. Politicization instead manifests as the manipulation of intelligence after a policy has already been decided on, when policymakers pick and choose information to support a decision they have already made.

Involving intelligence officers from the outset of the policy process could even reduce the risk of politicization by helping policymakers to come to better conclusions on their own. Independence is desirable and objectivity is necessary, but relevance is mandatory. Intelligence officers must, as Jennifer Sims put it, be less focused “on finding some objective truth in the facts themselves” and more focused on “helping their own side win.”

The next generation of policymakers will accept nothing less. They expect more — more access, more transparency, more collaboration. We need a model of intelligence service that gives them all of these things and that takes advantage of everything we have learned in the last three-quarters of a century about how people think, learn, and collaborate. Rather than seeking merely to provide input into a policymaker’s decisions, intelligence officers should instead seek to actively help them make better ones.

Zachery Tyson Brown is a strategic futurist working at the intersection of disruptive technology, organizational design, and national security. A former intelligence officer and United States Army veteran who served in Iraq and Afghanistan, Zach is now a security fellow at the Truman National Security Project, a proclaimed U.S. Army Futures Command “mad scientist,” and a Military Writers Guild board member.

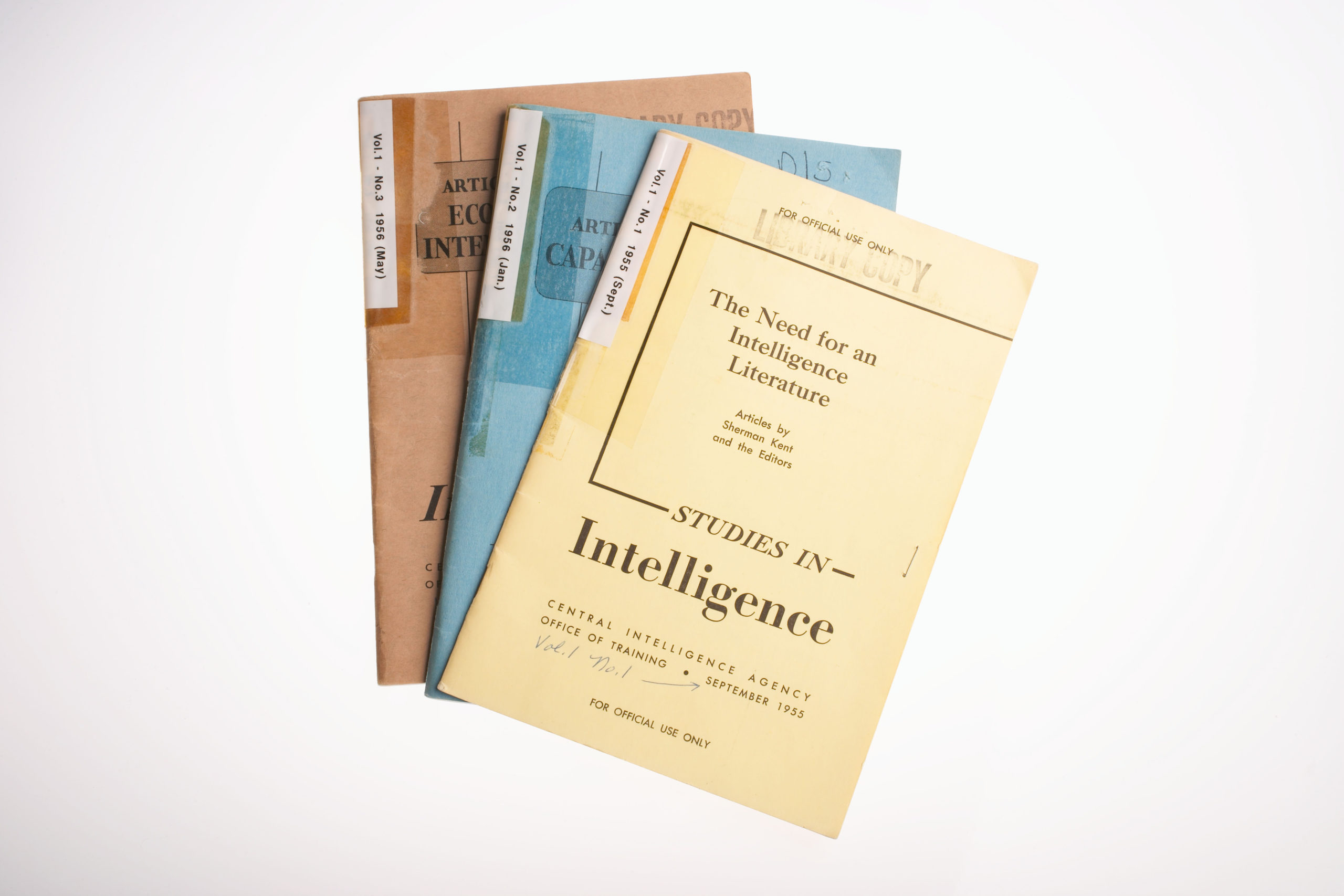

Image: CIA