As Israel, Bahrain, and the United Arab Emirates Normalize Ties, China Looks on Warily

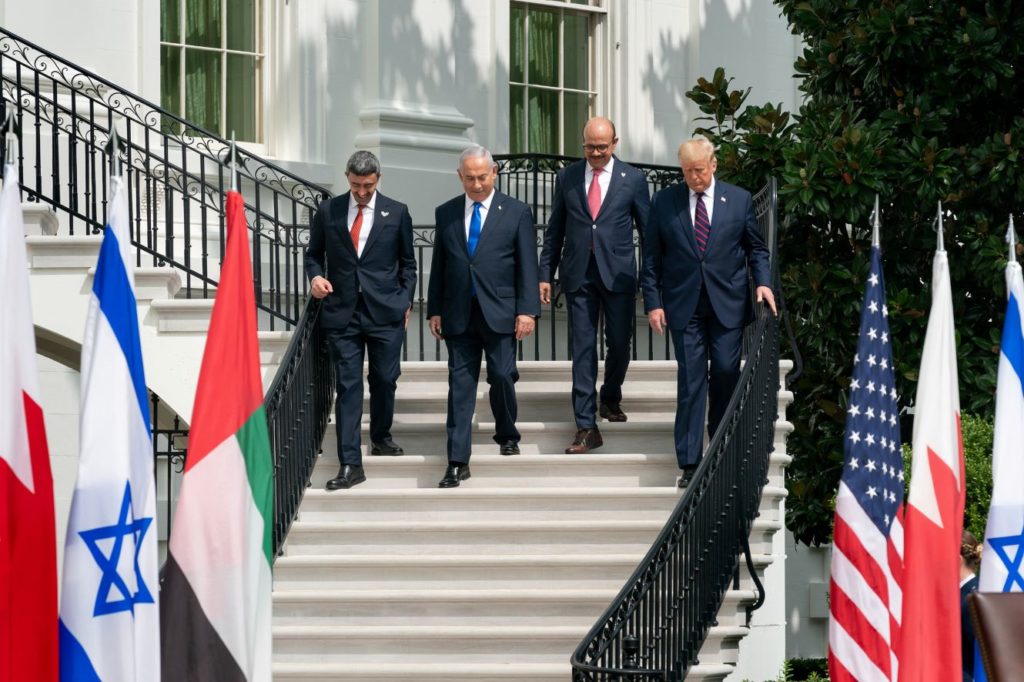

In a world starved for good news, the normalization agreements that Israel recently signed at the White House with the United Arab Emirates and Bahrain were met with near-universal praise. In a region more often associated with risk, the deals seemed to signal opportunity — for stability, for peace, and for profit.

One place where the news was not greeted so effusively, however, was in Beijing, where a government spokesman barely acknowledged the agreements despite China’s strong relations with both Israel and the Gulf Arab states. China’s wariness may turn out to be well-founded. While the growing Arab-Israeli rapprochement may be good for the Middle East, it poses problems for Chinese strategy in the region.

The most immediate benefit of the normalization agreements is likely to be economic. Up to now, Middle Eastern countries have traded heavily with China, but very little among themselves. China in recent years has been a dominant source for imports and destination for exports for almost every country in the region. In 2019, for example, the Middle East as a region exported more than three times as much by value to China than it did to the United States. Viewed at the country level, this dependency appears even more acute: Oman, for example, sends more than 40 percent of its exports to China, whereas Egypt imports nearly 25 times as much from China as it exports.

These unequal trade dynamics have conferred on Beijing enormous leverage of the sort that in other contexts — whether imposing sanctions on South Korean businesses in retaliation for U.S.-South Korean missile defense cooperation in 2017, withholding rare earths from Japan in 2010, or restricting imports of Philippine bananas in 2012 — it has not hesitated to use for political ends. This in turn has made regional states resistant to calls from Washington to reduce their dependence on China, even as Beijing has made inroads in strategic areas such as the provision of 5G and surveillance technology. This dependence is not only the result of trends such as America’s growing energy independence, but the Middle East’s own meager internal trade. Whereas about 60 percent of the European Union’s trade, for example, is internal to the region, intraregional trade in the Middle East barely tops the single digits, behind that of almost every other region of the world.

Israel’s deals with the United Arab Emirates and Bahrain could help to reverse these trends. Both Israel and the United Arab Emirates are among the region’s top three sources and destinations for foreign direct investment, meaning that each could offer the other an alternative to the Chinese capital, whichexposes them both to political demands from Beijing as well as irritation from Washington. Furthermore, companies like DP World, the Dubai-based port operator that is the world’s fourth largest, could offer alternatives for projects like the operation of Haifa’s port, a portion of which was awarded to Shanghai International Port Group to the chagrin of the U.S. Navy’s Sixth Fleet, which makes calls there.

The normalization deals may also complicate Beijing’s diplomatic approach to the Middle East, which might be described as “friends with everyone, allies with no one.” China studiously avoids the appearance of taking sides in the region’s manifold conflicts, ensuring, for example, to sign nearly identical agreements in Riyadh and Tehran in 2016 during President Xi Jinping’s first visit to the region, and hastening to recognize even the Hamas-led Palestinian Authority government in 2006 despite Beijing’s professed opposition to Islamism.

As the region’s political blocs become more coherent, however, this balancing act may prove more difficult. An isolated Israel, frequently and disproportionately on the receiving end of international opprobrium, has long needed any friends it could get, meaning it was in no position to rebuff China’s friendship despite Beijing’s support for Iran. This will be less the case as Israel is embraced by its neighbors. Likewise, a normal relationship with Israel gives the United Arab Emirates more options — not just for capital, but for security assistance, political support, and any number of other benefits for which states of the Middle East have long had to look outside the region. Together, Israel, the United Arab Emirates, and Bahrain may prove more able to hold China accountable for its regional policies than each felt emboldened to do separately.

Finally, the Israeli deals with the United Arab Emirates and Bahrain may be an important step in the formulation of a new U.S. strategy in the Middle East that preserves American influence there while freeing resources to focus on great-power rivals like China and Russia. America’s being tied down in the Middle East has proved a double benefit to Beijing. Not only has China doubtless welcomed Washington’s seemingly endless Mideast distractions, but it has been able to free-ride on U.S.-provided security in the region, without which its economic investments and oil routes would be more vulnerable and would demand the commitment of scarce Chinese diplomatic and military resources. These benefits for Beijing have been ironically amplified by persistent anxieties among U.S. regional partners — stoked in part by political rhetoric in Washington — that American forces may depart. This has fueled a tendency on the part of regional states to hedge their bets and seek out greater cooperation with China and Russia, including in the form of arms purchases.

Israel’s rapprochement with its Gulf neighbors may spell the beginning of the end of China’s free ride. While scaling back American ambitions in the region is important to successfully shifting the U.S. national security emphasis to Asia, it also carries risks, as American interests — whether the prevention of terrorism or countering nuclear proliferation — will continue to face threats emanating from the Middle East. For this reason, Washington has increasingly sought to work through partners. Doing so successfully depends to a great extent on those partners’ capabilities, and their willingness and ability to work together. The United States, regardless of who wins the presidency in November, is likely to seek to use the recent normalization deals as the seed for a nascent regional security partnership — one in which American allies work jointly to address mutual threats with modest, high-end assistance from the United States. What’s more, any such partnership is likely to be bound together by American military systems and training, narrowing or closing off potential inroads for Russian and Chinese arms sales. If such an effort is successful, the United States will be able to more confidently shift forces to other theaters while preserving its regional influence.

None of this is to say that the normalization agreements will be all bad for Beijing, or an unalloyed good for the United States. The deals are not targeted at China. The states involved will maintain close commercial ties with Beijing, and will resist — perhaps now in concert with one another — anything they view as an unreasonable effort by Washington to curtail them. What’s more, among the initial targets of Israeli, Emirati, and Bahraini cooperation are likely to be Turkey and Qatar, both close partners of the United States. It is just American policymakers’ luck that as one rift between U.S. allies is closing, another seems to be yawning ever wider.

Yet whatever reservations may be in order, the Israeli-UAE and Israeli-Bahraini agreements are, beyond a doubt, a net positive for U.S. interests in the region and a challenge for American rivals. China in particular will find its enormous economic influence in the region — and the diplomatic leverage it buys — diminished, and its ability to maintain cordial and profitable relations with all sides of the region’s conflicts undermined. This in turn may force Beijing to revise its strategy in the region, becoming more responsive to partners’ political demands, to which its large regional economic footprint has left it exposed. Perhaps even more important for Beijing and other U.S. rivals, however, the agreements could help free up the United States to finally shift more attention toward Asia. And they underscore a key comparative advantage the United States enjoys as great-power competition heats up once again — its continuing ability to attract allies and build partnerships among them.

Michael Singh is managing director and Lane-Swig senior fellow at the Washington Institute for Near East Policy.