Making the U.S. Military’s Counter-Terrorism Mission Sustainable

One of the many hallmarks of the Trump administration has been its capricious approach to troops deployments, especially ones related to counter-terrorism. President Donald Trump has zigged and zagged on whether to maintain troops in Afghanistan, Iraq, and Syria, sometimes sending Pentagon planners scrambling to keep up. Over the weekend, his administration threatened to pull out U.S. forces from Iraq as a way to pressure the government there to rein in Iran-backed militia groups. Meanwhile, in the background, Defense Secretary Mark Esper has been conducting a review of each combatant command to ensure they have the right mix of personnel and resources to meet the 2018 National Defense Strategy’s priorities. The review has not been entirely devoid of drama. It advocates reducing the U.S. military footprint in Africa, a move that has engendered pushback from Congress and U.S. allies. One should not equate Trump’s manic demands, which appear driven almost entirely by electoral calculations, with Esper’s more sober review, but both highlight the challenges of reducing the military’s counter-terrorism mission.

The 2018 National Defense Strategy made a stark declaration, “Inter-state strategic competition, not terrorism, is now the primary concern in U.S. national security.” The military’s counter-terrorism mission is not going away, however, and likely will require attention, resources, and manpower for the foreseeable future. In addition to exerting ongoing pressure on terrorist organizations, American forces enable intelligence collection — especially in hostile environments — and provide the means to conduct swift action against individuals and networks involved in plotting, directing, or attempting to inspire attacks against the United States. A military counter-terrorism presence can facilitate activities conducted by civilian departments and agencies as well as make U.S. partners more effective. This is not an argument for maintaining the status quo, which appears unsustainable and disproportionately large relative to the current terrorist threat, but rather an affirmation that the military still has an important role to play in counter-terrorism. The issue at hand is, or should be, how to adjust this role relative to the terrorist threat and other U.S. priorities.

Two years after the publication of the National Defense Strategy, the Department of Defense is still working on how to rebalance its counter-terrorism mission in line with this new prioritization. One of the reasons it is struggling is that it lacks a rubric for doing so. Almost two decades after 9/11, the Pentagon still has not developed a comprehensive framework for balancing risks and resources when it comes to counter-terrorism. As I argued in a recent paper for the Center for a New American Security’s Next Defense Strategy project, the absence of such a framework makes it more likely that the Defense Department either remains overly committed to counter-terrorism because it lacks a mechanism for driving sustainable reform, or overcorrects in a way that takes on unnecessary risk of a terrorism-related contingency that threatens the United States and disrupts its shift toward other priorities.

The Need for a Sustainable Counter-Terrorism Mission

In a speech earlier this month, Esper blamed the focus on counter-terrorism for leaving the military less prepared for a high-end fight against near-peer adversaries. This is a convenient excuse that covers over a range of failures to modernize the force as Paul Scharre, my colleague at the Center for a New American Security, has pointed out. The Pentagon was steadily investing billions to deter and fight big wars against nation-state adversaries while U.S. troops were fighting in Iraq and Afghanistan. It just wasn’t investing in the right weapons systems, according to Scharre, or properly rethinking how the military needs to fight future wars. Yet while the focus on counter-terrorism might not be the primary reason for the military’s failure to modernize effectively, it continues to strain U.S. readiness.

When it comes to resourcing America’s counter-terrorism operations, it is important to distinguish financial resources from the people and platforms that money pays for. There is no line item for this mission, which makes estimating potential budget savings difficult. Expeditionary warfare is expensive. The training and personnel pipeline for special operations forces, who bear the brunt of counter-terrorism missions, is also more expensive than for conventional forces. The operating costs of the conventional assets still used for counter-terrorism, especially air platforms, can also add up. Even so, potential cost savings from cutting counter-terrorism expenditures is likely to be small relative to the overall defense budget. The Pentagon should still seek ways to reduce financial resources, but this over-spending is less problematic than the readiness issues that it is facing.

The days of massive counter-insurgency campaigns are long gone, but the United States still has thousands of troops deployed for this mission. There are approximately 8,500 in Afghanistan (although that number is set to decline to 5,000 by November), 3,000 in Iraq, and smaller numbers in Syria, Somalia, Yemen, the Sahel, and elsewhere. These forces are mainly working by, with, and through local partners — who do the heavy lifting — and conducting direct action strikes to supplement these indigenous efforts. These missions, many of which are intended to suppress terrorist threats and maintain a modicum of political stability in conflict zones, have the impression of sustainability because they require comparatively smaller numbers of forces than large-scale counter-insurgency efforts and rely heavily on local forces. Yet for many local partners to be effective, they need the U.S. military — typically special operations or conventional military forces, but also CIA paramilitary forces or even private military contractors — to provide intensive operational support. This, in turn, necessitates the use of enabling platforms like intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance; close air support; airlift; and medevac. These platforms are required for unilateral raids conducted by U.S. special operations forces as well.

Even airstrikes conducted by drones typically require forces on the ground. The level of investment in terms of troops and platforms necessary to maintain the current scope and tempo of “light-footprint” operations may be unsustainable in terms of available forces and platforms given the Defense Department’s prioritization of strategic competition with nation-states.

Special operations forces, who carry a disproportionately large share of the burden when it comes to counter-terrorism deployments, are “fatigued, worn and frayed around the edges,” according to a comprehensive review conducted at the direction of the commander of U.S. Special Operations Command. Even if this were not the case, special operations forces cannot maintain this operational tempo while simultaneously contributing to strategic competition as envisioned by the National Defense Strategy, preparing for a potential conflict with a near-peer competitor, and meeting their goal of a 1:2 deployment-to-dwell ratio. The problem is not simply the overuse of special operations forces, but also the misuse of different special operations elements. The “all hands on deck” approach that defined the last two decades combined with the absence of a framework for adjudicating missions and resources has created an environment in which various special operations forces are used for the wrong purposes. For example, units assigned global response missions against imminent threats, such as the Army’s Delta Force and some Navy SEAL teams, have been used for training missions, while Army special forces teams that should be focused on training and advising have been called upon to conduct direct action missions.

Moreover, special operations forces don’t travel alone. The Pentagon continues to dedicate enabling platforms — such as manned and unmanned aerial platforms used for intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance and armed overwatch, as well as manned platforms for electronic warfare, airlift, and medevac — to support counter-terrorism. These platforms also require people to use and maintain them. Special operations forces need additional logistical support as noted above. As a result, conventional forces continue to deploy in support of counter-terrorism missions despite the services increasing focus on high-intensity conflict. Of greater concern, the overuse of some of these platforms for counter-terrorism has created readiness issues, most notably for the Air Force because its bombers and fighter jets have been used for direct action. In other words, the Pentagon not only failed to invest in the right types of assets needed for a high-intensity conflict, it also wore down some of the assets it did invest in by over-using them for counter-terrorism.

Spinning its Wheels

Optimizing the U.S. military for strategic competition and a potential conflict with a near-peer competitor will necessitate more than just reigning in the counter-terrorism mission. This does not obviate the need for reform. The issue is not whether the Defense Department is devoting too much or too little to counter-terrorism in absolute terms, but rather how forces, platforms, and resources are allocated relative to the terrorism threat and other priorities. Risk aversion regarding the potential of a future terrorist attack is part of the problem, but it is also the case that some of the global combatant commands use counter-terrorism as a rationale when writing requirements for special operations forces and enabling platforms. The Trump administration’s escalatory approach towards Iran — and the ways in which this has become intertwined with the U.S. counter-terrorism mission — compounds the problem.

The most obvious danger of failing to develop and implement a framework for conducting a more sustainable counter-terrorism mission is that this mission remains unsustainable. There are other dangers, however, one of which is a department-wide overcorrection that increases the risks of a terrorist attack against the United States or its interests overseas. Another is a disjointed transition away from counter-terrorism, which already appears to be occurring according to members of the special operations community with whom I have spoken. The Army is pulling away many of its intelligence specialists and technical capabilities from the counter-terrorism mission. This has not been coordinated with a commensurate drawdown in Army special forces counter-terrorism operations, however, making these operations more difficult and riskier. The Air Force has also pulled back support for counter-terrorism operations, creating pressure to fill looming gaps in the various types of enabling support that U.S. and partner forces have come to rely on.

It’s tempting just to call for a “zero-based” review of the entire counter-terrorism mission. The principle of such a review is that all counter-terrorism deployments would need to be justified against a goal of zero operational forces deployed. The problem is that such a review would be based on a static assessment of threats at the time the review is being conducted, whereas the threat environment is dynamic. Realizing the type of systemic change needed will require putting in place a framework for aligning threats, missions, resources, and risk acceptance, and a program for conducting net assessment of the counter-terrorism mission. Because of the potential of unforeseen events, any effort to scale back the counter-terrorism mission should also include contingency planning. Absent clear direction and backing from the secretary to make all this happen, there’s a real risk that the Defense Department will keep spinning its wheels.

A Comprehensive Framework

A comprehensive framework for assigning counter-terrorism missions is critical for avoiding the extremes of path dependency on the one hand and overcorrection or a disjointed transition on the other hand. It would also provide a mechanism for recalibrating counter-terrorism-related force structure and posture requirements as terrorist threats and Defense Department priorities evolve. Finally, such a framework could also help the Pentagon evaluate the counter-terrorism-related infrastructure that it has developed since 9/11: authorities and execute orders, policy shops, and military task forces, including the role of the theater special operations commands under the geographic combatant commands.

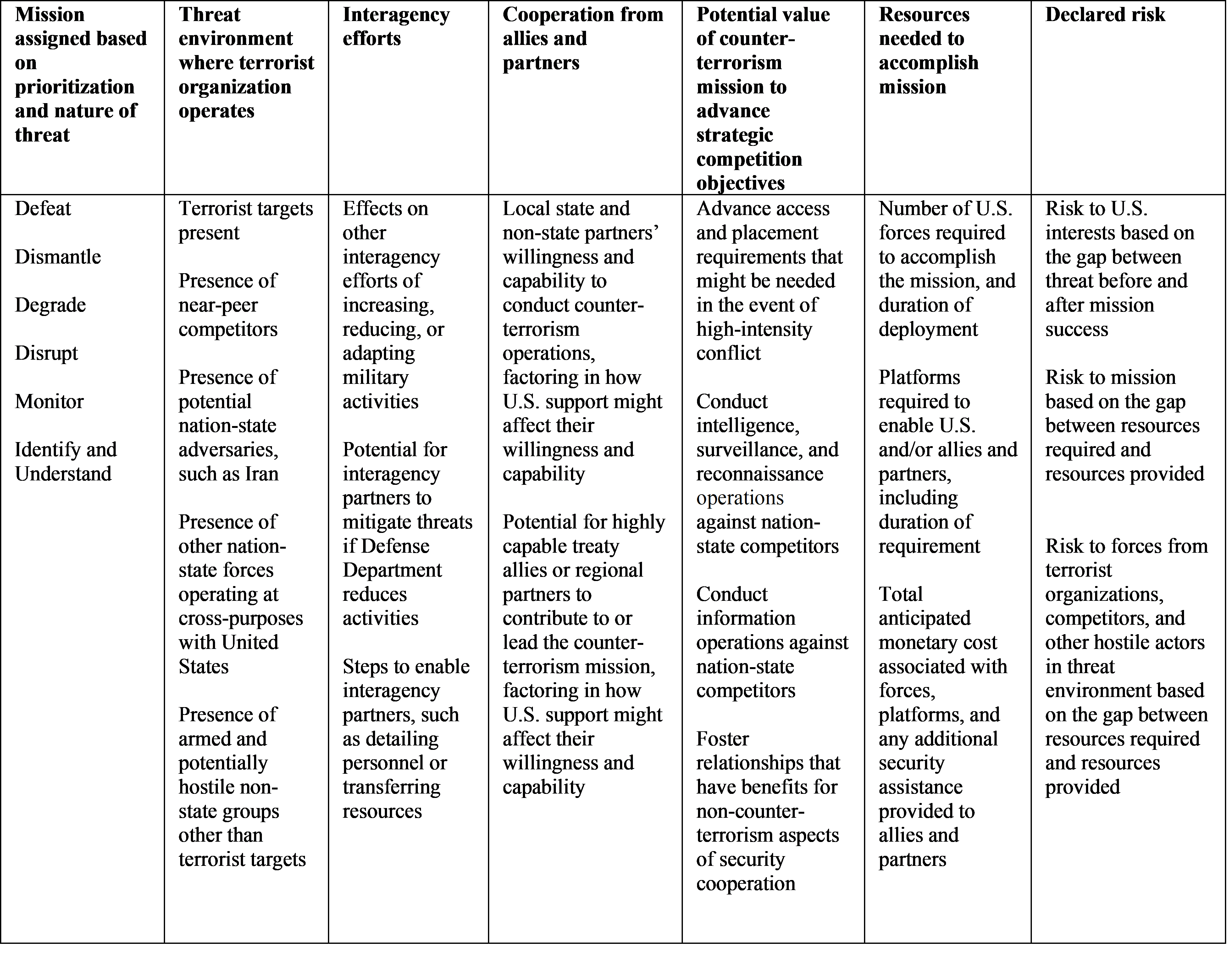

The framework below provides one model. It would need to be pressure tested to determine whether these are the right factors to include and how the Defense Department should weigh them. The Pentagon could use planning scenarios to flesh out and standardize its approach to prioritization and threat assessment, the assignment of missions, and the identification of resources required to accomplish a mission.

The first step the Defense Department needs to take is to create a standardized, universal list of terrorist groups and assign groups to a fixed number of prioritized tiers based on the level and nature of threat. This may seem like a no-brainer, but almost 20 years after 9/11 the Pentagon still lacks a single list that includes all the terrorist groups it is combating. Creating a standardized list will do more than just identify the universe of potential terrorist groups to combat. The Defense Department has had a tendency to prioritize terrorist threats without always doing threat assessments first. Creating a universal list will enable the Defense Department to identify its counter-terrorism priorities based on the same set of factors, in terms of the groups themselves and the types of threats these groups pose to the United States. This list will need to be a living document, evolving in line with the changing nature of the terrorist landscape. For example, in the future, near-peer competitors may increase their use of nonstate proxies or support for terrorism to advance their interests below the threshold of conflict. Of course, if a similar document exists elsewhere in the government and is sufficient for the Defense Department’s purposes, it could adopt that one.

Once the Pentagon has identified the terrorist groups it is concerned about and tiered them based on the threats they pose, it can assign a specific mission to each group. The chart below suggests six missions — from most to least intensive — based on the priority accorded to a group: defeat, dismantle, degrade, disrupt, monitor, and identify and understand. Each mission should include criteria for defining and achieving success, which in turn should enable defense planners to identify what actions are necessary. This is important not only for ensuring that the Defense Department achieves its counter-terrorism objectives, but also may help reduce the potential for counter-terrorism to be used as a rationale for employing troops and platforms for purposes that are not terrorism related.

Figure 1: Framework for Assigning and Resourcing Counter-Terrorism Missions

Next, the Defense Department should assign resources to each mission (Column 1 lists the possible missions described above that the Pentagon might assign) based on the factors outlined in the chart. Columns 2–4 include factors for consideration that could enable or encumber pursuit of the mission, as well as possibly increase risk to U.S. forces. When considering the threat environment, the Defense Department should assess not only the risks from the terrorist targets, but also those posed by other actors (e.g., near-peer competitors and nation-state adversaries) that are physically present or able and intent on projecting power into the country or region in question. Regarding the contributions that other U.S. government agencies (e.g., CIA, State Department, U.S. Agency for International Development), allies, and partners could make to a counter-terrorism mission, it will also be important to consider whether and how their efforts might rely on U.S. forces or platforms. Depending on the circumstance, the intelligence community or State Department may develop or expand cooperation with and support for partners’ law enforcement, border authorities, and intelligence communities. Column 5 factors in the potential value of a counter-terrorism mission to advancing strategic competition objectives. There are costs and benefits to including this in the decision calculus. It could enable the Pentagon to maximize the utility of its forces and resources in certain places, but also might be used to justify counter-terrorism activities that the Pentagon otherwise would not conduct or sap resources that could be used to advance strategic competition objectives more effectively elsewhere. Column 6 determines the resources required to accomplish the assigned mission, factoring in the elements identified in Columns 2–5. Column 7 identifies potential known risks to U.S. interests, the mission, and U.S. forces if the resources required are provided.

Finally, on an ongoing basis, defense planners ought to assess the cumulative resources dedicated to the entire counter-terrorism mission relative to the overall terrorism risks that the president and the secretary of defense are prepared to accept, and then re-adjust individual missions and resources accordingly. If the Pentagon remains over-resourced toward counter-terrorism relative to requirements for other priorities, the approach outlined here would enable the secretary to make an informed decision about whether to accept more risk from terrorism, and, if so, where to accept that risk.

Pursuing missions in accordance with this framework should help adjust direct action missions and train, advise, and assist missions that involve aggressive operational support in line with current terrorism threats and other priorities. This would likely free up special operations and conventional forces and resources for other National Defense Strategy priorities. It also would inform decisions about where the Defense Department engages in more routine training and provides other security assistance for counter-terrorism capacity building, as well as how much and what type of assistance. Even a scaled-back counter-terrorism mission will still require considerable intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance, as well as some logistical support and armed overwatch. Demands for airlift, quick reaction forces, and medevac might decline, although it is possible that a smaller footprint leads to less force protection on the ground, which in turn could affect demand for these capabilities. Relying mainly on unmanned platforms for intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance; close-air support; and precision strike, in the types of austere and permissive environments where the United States is likely to conduct counter-terrorism missions could further reduce the strains on readiness.

While the framework above allows for recalibration, conducting a net assessment would significantly enhance the Defense Department’s ability to prioritize, adapt its lines of effort, and ensure the effective allocation of resources relative to terrorism-related risks. The Defense Department currently lacks this type of net assessment process, which should include several elements. First, the Pentagon needs to explicitly identify its criteria for measuring effectiveness for the overarching counter-terrorism mission, as well as the individual missions that make up its component parts. Second, it should develop metrics based on the actions required for success and the way the military defines success for each mission. These metrics should factor in assumptions made regarding interagency efforts and cooperation from allies and partners. Third, the Defense Department should use these metrics to drive the collection of data about U.S. counter-terrorism efforts and those of its partners, the behavior of terrorist adversaries, and the effects on the civilian population in the country or region where these efforts occur and terrorists operate. Fourth, although metrics should be tailored to actions and therefore need not be universal, the Pentagon should develop a common methodological toolbox for assessing effectiveness.

Because there may be instances in which contingencies arise (e.g., terrorists seize strategic territory, or develop or reconstitute external operations capabilities that pose new threats to the United States) the Pentagon should also ensure it has adequate contingency planning in place. It will be critical to ensure ongoing intelligence collection — unilaterally by Defense Department elements or other members of the U.S. intelligence community, or provided via intelligence liaison with reliable allies and partners — for the purposes of indications and warnings. The Pentagon, in coordination with other U.S. government agencies, should also develop a plan for emplacing additional intelligence collection assets quickly if necessary. Planners also will need to ensure the global force readiness required to move military assets into various locations where the United States scales back its efforts. These assets could be required for a range of operations, including increased operational support to allies or partners, limited counter-terrorism strikes, and even a troop surge of several thousand U.S. forces. Pentagon planners will need to identify the level of persistent forward engagement necessary to enable access and placement to support this range of operations.

Contingency planning should factor in potential contributions from and the effect on allies and partners as well. In areas where the U.S. military pulls back considerably, partners will need to assume more of the burden and more risk. Preparing them for this eventuality will be critical. This means working with the partner forces to identify and address priority gaps in capabilities, equipment, and relationships with other security forces, among other things. There may be instances where allies and high-end regional partners have sufficient capabilities and vested interests in counter-terrorism and in their relationship with the United States to make joint contingency planning worthwhile. Where this is not the case, the Pentagon at the very least should identify close allies and high-end regional partners who might be able to assist in the event of a contingency, and lay the groundwork for coordinating with them.

Conclusion

The over-militarization of U.S. counter-terrorism efforts has had pernicious consequences both for these efforts and the U.S. military. Focusing on interstate strategic competition requires investing the mental energy necessary to develop a more sustainable approach to counter-terrorism. In the absence of such an effort, the military risks remaining overly committed to counter-terrorism because of inertia, or overcorrecting in a way that makes it more likely the United States will face a terrorism-related contingency that could disrupt its shift toward interstate strategic competition. Failing to do this intellectual homework also risks leaving the Pentagon unprepared to respond effectively in the event near-peer competitors increase their use of proxy warfare or support for terrorism to distract the United States and sap its resources, or as part of a larger conflict. It is understandable for Defense Department leadership to want to turn the page on counter-terrorism, but equally critical that they realize the page won’t turn itself and that there are risks to closing the book too quickly.

Stephen Tankel is an associate professor at American University, an adjunct senior fellow at the Center for a New American Security, and a senior editor at War on the Rocks. He has served on the House Foreign Affairs Committee and in the Office of the Under Secretary of Defense for Policy. Tankel is the author most recently of With Us and Against Us: How America’s Partners Help and Hinder the War on Terror.

Image: U.S. Army (Photo by Spc. Sara Wakai)