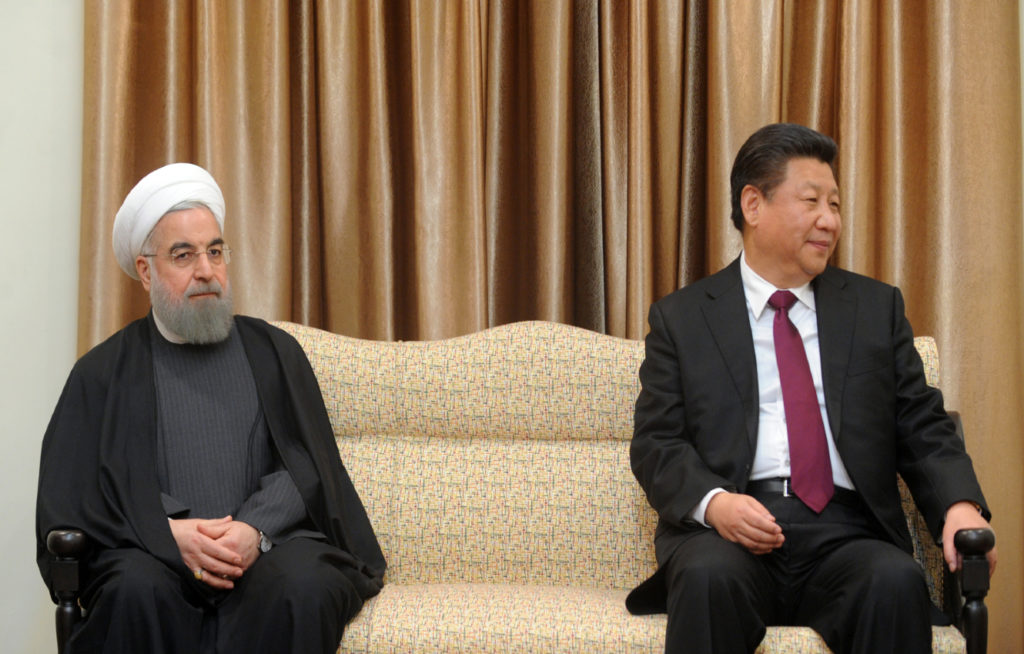

The Prospects of a China-Iran Axis

What will ties between China and Iran look like in the future? A recently leaked draft of a partnership agreement between Beijing and Tehran may provide some insight. The document outlines a framework for increased Chinese investment in Iran, strategic cooperation, and Iran’s integration in China’s Belt and Road Initiative. The potential agreement has rattled some in Washington, stoking concerns that America’s assertive foreign policy has solidified a dangerous alliance between key, anti-American powers in East Asia and the Middle East.

The unsigned draft agreement was likely leaked by the Iranian government — the document is in Farsi and Tehran seemed eager to publicize it. In contrast, Beijing appears hesitant to address the deal in public, let alone issue any kind of endorsement. China’s unenthusiastic reaction may be the result of annoyance at Iran’s leaking of the document, a cost-benefit calculation that publicly endorsing it could further poison China’s vital relationship with Washington, and/or concerns that it would inflict reputational harm on Beijing among its other partners in the Middle East. Nevertheless, China has not renounced the document either.

If this deal is ultimately signed and implemented, then it could represent a major acceleration of two current trends: China’s growing investment in the Middle East and the consolidation of an authoritarian anti-American bloc of countries. However, the act of signing such an agreement does not eliminate existing constraints in Sino-Iranian cooperation, including Iran’s unappealing investment environment, China’s historic unwillingness to invest in a country purely for geopolitical ends, and limitations on what each can offer the other in coping with their shared foe — the United States. These obstacles will make the majority of the joint energy and infrastructure projects listed in the document, reportedly valued at around $400 billion over 25 years, difficult to realize. In short, policymakers should pay close attention to Sino-Iranian ties — but they shouldn’t overreact.

Despite concerns about the dangers of a new China-Iran partnership, Beijing will find it difficult to uphold grandiose promises of investment, and any joint projects that do move forward will likely be negotiated under highly unfavorable terms for Iran. In addition, cooperation against the United States has limited potential because neither country can resolve the core challenges that the other faces vis-à-vis Washington. Therefore, while Sino-Iranian ties will continue to be of interest to analysts and officials, it would be premature to cite the leaked draft as evidence of a concrete alliance. Nor does it necessarily indicate that “maximum pressure” has failed or backfired — in fact, it may actually corroborate the view that the U.S. strategy is working to a degree. This essay examines the constraints that Iran and China will face in seeking to increase commercial cooperation, the limited geopolitical advantages such a partnership is capable of yielding, and how to understand Iran’s intense interest in deeper ties with China.

Don’t Expect Smooth Sailing

Chinese investment in Iran — which has averaged $1.8 billion per year since 2005 — is unlikely to dramatically increase any time soon. American secondary sanctions will continue to act as a major deterrent to foreign firms looking to enter the Iranian market. Thus far, the fear of being cut off from the U.S. market and financial system has caused many Chinese companies to either suspend cooperation with Iran or withdraw from that market entirely. Beijing’s cautious approach to this issue is evident from the data regarding its 2018 to 2019 crude oil imports, as its purchases from Iran declined by 50 percent (about 300,000 barrels per day) in a single year due to U.S. sanctions. At the same time, shipments from alternative suppliers in the region such as Saudi Arabia and Iraq increased by a combined total of more than twice that amount.

China’s enthusiasm for investing in Iran has proven to be quite weak in recent decades. From 2005 to 2018, Chinese firms invested less in Iran than they did in Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates, and only slightly more than they did in Egypt (which has been described by one Egyptian tycoon as the “worst investment climate in the Arab world”). In addition, anecdotal evidence points to the fact that Chinese investors “do not believe that it is worth doing business with Iran, given the difficulties involved.”

What Do China and Iran Get Out of Closer Ties?

Leaving purely economic considerations aside, one might assume that Beijing and Tehran will increase cooperation in their struggle against the United States. However, China is unlikely to bail out a country for purely geopolitical reasons. In Venezuela, for example, China demonstrated a pragmatic rather than ideological approach: It sought to avert the collapse of a regime which owed it billions of dollars, while at the same time avoiding a substantial increase in investment into what is obviously a corrupt, inefficient, and unstable economic system. The Venezuela example provides good reason for skepticism toward the prospect of a geopolitically motivated Chinese economic bailout of Iran — like Venezuela, an oil-rich, anti-American bastion experiencing diplomatic and economic isolation abroad and dysfunction at home.

Would a deeper Iran-China partnership be capable of resolving the major problems each faces vis-à-vis Washington? Not directly. China is unlikely to provide adequate investment to solve Iran’s economic woes, and Iran cannot provide China with the trade and technological advantages to mitigate recent U.S. steps in great-power competition. Instead, decision-makers in both countries may see value in the potential leverage that their bilateral relationship provides should they deem it necessary to return to the negotiating table with the United States. For Iran, its “burgeoning” economic relations with China would allow it to appear less desperate in future negotiations for sanctions relief, and for China the promise of reducing cooperation with Iran may earn it concessions from Washington on issues it considers to be of higher priority.

The assessment that this leaked draft and a potential Sino-Iranian partnership constitute a major blow to U.S. “maximum pressure” on Iran appears premature. On the contrary, it is entirely conceivable that the document was leaked by Tehran as a desperate response to the partial success of America’s Iran policy. Iran’s dismal economic outlook and the regime’s recent blunders have created intense pressure on the government to present some good news to the public (e.g., Chinese investors lining up to pour money into Iran) in order to demonstrate the regime’s competence and provide a sense of hope for the future. However, these Iranian “breakthroughs” do not always reflect reality. In addition, Tehran promoting the prospect of a Chinese economic lifeline may presage an effort to return to the negotiating table with the United States under more favorable conditions. All the same, Washington’s success in building up pressure against Iran does not yet warrant a declaration of victory — it remains to be seen whether the White House will convert these gains into the advancement of long-term strategic goals such as maximizing the distance between Iran and a nuclear weapon.

If China proceeds to significantly ramp up its investment in Iran, it will have to price in the risks of domestic unrest, regional instability, and sanctions. In seeking to attract investment, Iran is analogous to a homeowner trying to sell a distressed asset with only one prospective buyer who has many other options — Tehran’s bargaining power is virtually non-existent. Unverified reports indicate that Tehran promised Beijing a 25-year supply of oil at a 32 percent discount. While the Iranian regime may find that arrangement to be preferable to its current state, in which oil exports have been reduced to around 10 percent of their 2017 numbers due to sanctions, it would also severely inhibit the possibility of future economic improvement if/when sanctions are lifted. The “joint projects” may turn out to be a fire sale of Tehran’s infrastructure and assets to China. Whether that is a positive or negative development for the involved parties remains to be seen, but if it is perceived as compromising Iranian sovereignty then it is likely to elicit a powerful response from the Iranian public, who have a profound and historic sensitivity to foreign interference in their country’s domestic affairs.

Looking Ahead

Declarations of partnership between Tehran and Beijing are unlikely to meet expectations. It’s difficult for China to rapidly increase investment in Iran: The country is unstable, U.S. sanctions raise costs for Chinese firms to do business there, and there are other markets in the Middle East that promise higher returns. China may, however, provide Iran with short-term leverage that it can use in future negotiations with the United States. Iran offers China little beyond discounted oil — which it gets from other regional sources — and an opportunity to further undercut U.S. interests in the Middle East. If past is prologue, neither economics nor geopolitics will provide adequate incentive for China to increase investment in Iran by an order of magnitude.

In Washington, opposition to a Sino-Iranian partnership will continue to be fierce, regardless of which candidate wins the upcoming presidential election. President Donald Trump has made antagonism toward China and Iran a cornerstone of his 2020 campaign’s foreign policy platform, as he did during his 2016 campaign. Though his rhetoric will presumably be quite different, former Vice President Joe Biden’s approach to national security also includes pushing back on Beijing (one of the few bipartisan issues in Washington today) and maintaining pressure on Iran until a new nuclear deal with more favorable terms can be negotiated.

Even if the overt elements of the partnership remain unfulfilled, real and harmful dangers of Chinese-Iranian cooperation remain. Intelligence cooperation between the two countries reportedly led to the decimation of the CIA’s collection capabilities. In addition, Chinese assistance with Iran’s missile program has intensified the threat Iran poses to the Middle East. However, Beijing’s assistance to Iran is based on opportunism rather than any particular affinity. Recent reports have revealed China’s role in developing nuclear facilities for Saudi Arabia, Tehran’s arch-rival.

China will continue to maneuver between regional powers in the Middle East. Beijing will not forego Saudi oil or trade with Israel and Turkey in order to more deeply entangle itself in Iran’s collapsing economy. Should Iran seek to return to negotiations with the United States, it may ultimately find that its public efforts to build closer ties with China have only served to intensify animosity toward it in Washington.

Amos Yadlin is the director of Israel’s Institute for National Security Studies. From 2006 to 2010 he was chief of Israeli military intelligence. You may follow him on Twitter @YadlinAmos.

Ari Heistein is a research fellow and chief of staff to the director of the Institute for National Security Studies. You may follow him on Twitter @ariheist.