Strengthening Industrial Base Decision-Making for Precision-Guided Munitions

In Troy, Alabama, working-class families are on the front lines of America’s defense industry. Lockheed Martin broke ground in Troy in May 2019 for a new facility to expand the production of long-range standoff missiles, including the Joint Air-to-Surface Standoff Missile-Extended Range. This site is intended to help meet the demand for “large ongoing and expected orders” of air- or sea-launched standoff missiles.

Long-range strike systems of the class produced in Troy would play an important role in a conflict with a country like China or Russia. The National Defense Strategy Commission highlighted the need for standoff weapons, stating that conflict with great powers “would entail significant demand for long-range, high-precision munitions so that U.S. forces can remain outside the range of advanced air defense systems.” It noted that more Defense Department investment is needed “to ensure a substantial, sustainable, and rapidly scalable supply of preferred weapons.”

For the Troy plant — and others like it — to meet expectations, the Pentagon needs to increase visibility into the supply chain supporting the production of these key munitions. Investments like the new plant in Troy are a first step. But the United States needs to ensure the underlying industrial base can support the surge production of not just one munition, but multiple munitions systems simultaneously. The knowledge and insight to properly assess industrial base capabilities requires not only data collection and curation, but the development and deployment of analytical capabilities designed to identify potential bottlenecks and offer strategies for mitigating such risks.

The Need to Surge

Inadequate inventories of long-range missiles have proven to be a contributor to unfavorable outcomes in recent wargames. In those simulations, the United States and its allies “run out of munitions fast,” hindering their ability to prevail in some scenarios. Indeed, various experts warn that under current readiness conditions “Americans could face a decisive military defeat.” The situation becomes more dire when considering a protracted conventional war, requiring a sustained surge across a number of munitions systems that rely on highly consolidated, and often fragile, supply chains. This is not a problem limited to munitions, as “America’s defense industrial base is designed for peacetime efficiency, not mass wartime production.”

Figure 1: A long-range, offensive missile being launched from an F-16 (U.S. Air Force Photo by Master Sgt. Michael Jackson).

The Defense Department needs more standoff munitions. But just as important, it needs the capability to recover quickly if its munitions reserves are rapidly depleted. Prohibitively long production lead-times of most key precision-guided munitions makes this proposition extremely difficult. The military requires an industrial base capable of maximizing production of a number of munitions simultaneously.

Currently, the Pentagon doesn’t have a department-wide understanding of the surge capacities and constraints in the defense industrial base. While individual program managers may understand the individual systems for which they are responsible, they are rarely aware of potentially competing demands. This could create bottlenecks if a number of systems, some built on shared production lines, need to surge simultaneously. Military readiness plans should systematically account for industrial base realities that dramatically affect surge. Specifically, planners should consider risk factors like shared and limited production of select systems and components, sole sources, and foreign dependencies. Without an enterprise-wide view of munitions challenges and possibilities, senior decision-makers will almost certainly be misinformed about the readiness and recovery risks facing the country.

The need to better plan for an unexpected disruption in the munitions supply chain is not new. As the past demonstrates, mobilization takes much longer than expected. Whether it’s unintentional (e.g., industrial accident, force majeure, pandemic) or deliberate (e.g., kinetic attack, economic coercion, decisions not to export high-demand items), the United States cannot count upon having much time to prepare for an urgent threat. Rather, it needs to invest ahead of time to be able to surge production of different items at the same time.

For many items, and munitions in particular, investing in additional system integrator-level production may not be enough. System integrator facilities (like the Troy plant) bring together all of the component and sub-component systems required for final missile assembly. They require sufficient inputs of components — inputs received on time and of requisite quality — from their suppliers in order to take full advantage of final assembly at maximum production rates. The problem of not receiving all the needed components is often exacerbated at lower tiers of the supply chain as components become more specialized, often provided by very few, or perhaps, by one producer — a single point of failure.

Military planners frequently underestimate the time needed to achieve readiness. One reason is that they don’t take a realistic account of lower-tier capacity constraints and the competing demands for shared components. Additionally, unanticipated supply disruptions, potentially induced by U.S. foreign dependency on components and materials, can make matters worse. While supply chains running through China, for example, pose strategic, financial, and technological risks, even U.S.-based supply chains may be particularly vulnerable to delays.

Several years ago, the Army’s expanded budget request for precision-guided munitions successfully stimulated a staffing and facility expansion in Rocket Center, West Virginia, where solid rocket motors produced by Northrop Grumman are used in different precision-guided munitions. This essential missile component has been a source of concern for the Pentagon. There are currently only two domestic suppliers of solid rocket motors used in the majority of the military’s missile systems, with foreign suppliers making up the balance for a small number of systems. Surging the production of multiple systems at once may not be possible if an essential system component is provided by a single supplier. The inability to fully produce all munitions at maximum capacity could lead to internal conflicts within the Defense Department regarding which missile system takes priority. Understandably, warfighters want the munitions called for in operational plans, not simply the one that’s ready at the moment.

While the new plant in Troy may be welcome, it’s not enough. Supplying the U.S. military so that it can compete with China and Russia requires a fundamental restructuring of industrial base planning and preparation practices. The Pentagon needs to build and aggressively maintain an enterprise-wide common operating picture of high-priority, precision-guided munitions supply chains. A continuously refreshed picture of these supply chains will help the military understand competing demands, bottlenecks, and potential supply disruptions at the lower tiers.

Today, unfortunately, individual munitions program managers do not systematically provide information to a central office in the Pentagon that can compare current and planned usage with the capacities of system integrators and component producers. The appropriate office to collect data on usage and capacities, especially among lower tier producers, is likely the deputy assistant secretary of defense for industrial policy. Doing so would allow such information to be integrated and assessed continuously. It would also provide the Defense Department’s planners and senior decision-makers with a more comprehensive picture of munitions readiness and how it is affected by competing demands and capacity constraints. According to the current National Defense Strategy, this is an increasingly important picture for the military to have in order to be able to act at the “speed of relevance.”

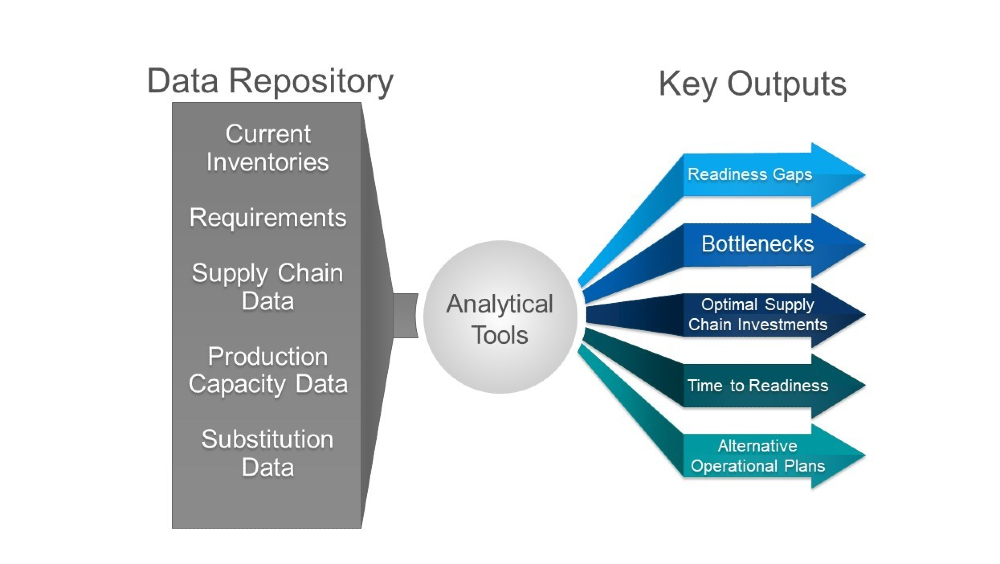

To construct a comprehensive picture of munitions readiness, the Defense Department needs to collect sufficient industrial base data and deploy advanced analytical tools to process the data. Using data and tools in tandem is the key to enabling analyses that identify supply chain bottlenecks, model outcomes of potential surge scenarios, and offer mitigation options. While the Pentagon already has quite a bit of data, these data are not yet integrated to enable a department-wide view of supply chain capabilities, constraints, and cost-effective mitigation actions. Nor are the data structured in consistent ways for such purposes. The Defense Department already has several types of integrating analytic software available that can serve as the foundation for timely evidence-based assessments and investments of the sort decision-makers need. However, leveraging existing analytic tools requires institution-wide support and an overarching framework (as shown below) to collect and curate industrial base data and generate key outputs, especially realistic estimates of the time and actions needed to achieve readiness, on a continuous basis.

Figure 2: Analytical framework for collecting and leveraging data to generate key outputs regarding munitions risks and mitigation options (Source: Image generated by the author).

Developing and using a common operating picture for the Pentagon’s munitions data will be difficult. However, this kind of innovation could have several tangible benefits by generating a better understanding of supply disruption problems; identifying surge opportunities and limitations in mobilization and recovery scenarios; encouraging innovation to maintain and expand production capacity; targeting lower-tier suppliers that need investment to alleviate bottlenecks and maximize production; and offering realistic estimates of the time needed to achieve readiness targets. Realistic estimates are a critical metric for war planners, particularly if supplies are disrupted. These forecasts will help inform back-up plans that may be needed in the event of munitions shortfalls.

Tasking warfighters with revising operational plans may be met with some resistance, but it’s one of many possible decisions that could be made to minimize the risk associated with insufficient inventories and to prevent the conflict from escalating beyond conventional weapons. Such decisions might require the substitution of one missile for another when realistic estimates of the number of munitions actually available during a conflict indicate supplies are limited.

There are encouraging signs that the military recognizes munitions shortage problems and is working to improve supply chain visibility. Recent industrial capabilities reports to Congress and the Pentagon’s response to Executive Order 13806 (which assessed America’s manufacturing and defense industrial base resiliency) highlight the need to strengthen the Defense Department’s understanding of vulnerabilities and constraints at lower tiers of the supply chain and to begin taking action to fix them.

Recommendations

The Defense Department should develop an integrated department-wide issue paper for precision-guided munitions to inform the future years defense program development process. This type of directive paper would give decision-makers realistic assessments of the industrial base by integrating demands, supplies, and constraints for a portfolio of munitions, rather than a collection of missile-by-missile assessments. The secretary of defense should also consider requiring system integrators to provide key capacity and component supplier data to the Pentagon as a condition of their future contracts.

The military should also base operational plans on realistic estimates of inventories for critical munitions. In this arena, the combatant commanders need to know how quickly they can expect to obtain more priority munitions in a crisis or major surge scenario. Specifically, they need to be sure that estimates take account of competing demands at the lower tiers. Furthermore, combatant commanders should be made aware of potentially dangerous foreign reliance for key components and materials at the lower tiers, particularly if that reliance is linked to likely adversaries in the crisis, and whether or not they are accounted for in estimates of time to readiness. Realistic estimates are needed to properly configure war plans, including plans that account for potential munitions inventory rebuilds in a post-conflict environment.

Right now, Defense Department planners need a practical action plan to collect, integrate, and analyze the right kinds of data to develop the budget for Fiscal Year 2022. The military would be better positioned to meet key readiness, mobilization, and recovery challenges in this new era of strategic competition if it develops and maintains a common operating picture of key precision-guided munitions and their underlying supply chains. Taking this type of enterprise-wide approach will ensure that new plants, like the one in Troy, meet expectations to help the United States prepare for and recover from potential future conflicts. And, if done right, this approach could serve as a model for a more integrated treatment of supply chains in other key parts of the defense industrial base and throughout other agencies in the government.

Julie C. Kelly is a research staff member at the Institute for Defense Analyses, a federally funded research and development center. In her more than 20 years at the institute, she has assisted the Office of the Secretary of Defense and other Defense Department agencies in addressing important national security issues, particularly those requiring scientific and technical expertise. Ms. Kelly specializes in conducting research on the defense industrial base, strategic and critical materials, precision-guided munitions, services contracting, and homeland defense issues. Ms. Kelly has a B.A. in economics and political science from the College of the Holy Cross, and an M.P.P from the University of Maryland.

Daniel E. Lago is a research staff member at Institute for Defense Analyses. Dr. Lago’s research has focused on the defense industrial base, strategic and critical materials, munitions, and modeling methods development. Dr. Lago has a B.S. in nuclear and radiological engineering from the University of Florida, and an M.S. and Ph.D. in nuclear and radiological engineering from the Georgia Institute of Technology.

James S. Thomason is the deputy director of the Strategy, Forces, and Resources Division at the Institute for Defense Analyses. He also leads the Strategy and Risk Program at the Institute for Defense Analyses. Over several decades, he has developed and implemented a number of decision tools and analytic processes for the Defense Department and other federal departments and agencies, both in the industrial base and supply chain area and for strategic-level decision-making. Dr. Thomason has published over 100 articles in these areas. He has a B.A. from Harvard University in political science and a Ph.D. in international relations from Northwestern University.

Image: U.S. Air Force (Photo by Airman 1st Class Christina Bennett)