How Iran’s Oil Infrastructure Gambit Could Imperil the Strait of Hormuz

A series of mysterious and seemingly random explosions continue to erupt across various parts of Iran this month, hitting sensitive military sites, as well as populated residential neighborhoods. Recent reporting suggests that these explosions may be part of a larger campaign undertaken by the United States and Israel to scale back the regime’s military and nuclear capabilities. Iran has been slow in its response, playing the long game. But the risk of escalation — unintentional or otherwise — looms large. And as the events of 2019 showed, the Persian Gulf and the Strait of Hormuz would be key areas where Iran might set its sights for an asymmetric response.

For decades, Iran has threatened repeatedly to obstruct naval traffic and disrupt the global energy market in the Strait of Hormuz. These threats had rung hollow for the most part — until now. Since the 1980s, such an extreme escalation from Iran amounted to a double-edged sword that also would prevent the country from using the strait for its own commercial lifeline. To take steps to close the strait would rattle Iran’s few remaining partners, chiefly China, whose energy needs are tied to freedom of navigation in the region and whose support the regime desperately needs to offset the effect of U.S. sanctions over the last 15 years.

On June 25, Iran’s President Hassan Rouhani announced a possible game-changer — that by March 2021, his country would upgrade its energy infrastructure to bypass entirely the Strait of Hormuz when it exports its oil. These upgrades would include a new pipeline and port facilities in the southern coast bordering the Gulf of Oman. And the recently announced comprehensive between Iran and China, a 25-year agreement that would cover energy, infrastructure, and military cooperation among other things, appears to stipulate the development of parts of this plan with support from Beijing. The deal also provides for the development of a new port that would rest comfortably in Chinese control. Rouhani’s ambitious new plan would allow Iran to close the Strait of Hormuz without losing its ability to export oil and forfeiting corresponding revenues. It would also allow Iran to sustain energy supplies to China, thus avoiding the political backlash that might come from taking more offensive actions in the Strait of Hormuz. Through this action, which seems to have been missed by many in the United States, Iran may be signaling its calculus is changing.

Tensions in the Strait

For years, Iranian political leaders and military officials used the following talking point to preempt increases in international economic pressure: If denied the ability to sell oil, a considerable economic lifeline for Iran, the country simply would close off the Strait of Hormuz. 20 percent of the world’s oil supplies pass through a sea lane that at its narrowest point is only 21 miles wide. If Iran were to follow through on its threat, the flow of energy would be disrupted globally and affect key economies worldwide — including that of China, the world’s foremost energy consumer and a key Iranian partner. The Islamic Revolutionary Guards Corps Navy since 2007 shares this area of responsibility with Iran’s conventional navy. But if Iran were to close the Strait of Hormuz, the Guards, not the Iranian navy, would take the lead in the effort. Despite routinely threatening to close the strait, Iran has never indicated it was prepared to execute such a plan. Nevertheless, on a number of occasions throughout 2019 and in recent months, Tehran has sought to demonstrate that it had the will and capabilities to do so if needed.

In the first half of 2019, as the Trump administration tightened the screws of its maximum pressure campaign, the Revolutionary Guards navy executed a dialed-up strategy in the waterways of the Persian Gulf. In May, Iran conducted attacks against four tankers off the Emirati coast using limpet mines. In June, the Revolutionary Guards Navy mined a Japanese tanker as well as a Norwegian tanker in the Gulf of Oman near the entrance of the Strait of Hormuz, leading to a spike in oil prices. A month later, it seized two British tankers in the same vicinity.

These actions were designed to increase the cost of Washington’s maximum pressure campaign. The Guards were also signaling to the international community that Iran was prepared to deliver on Rouhani’s promise dating back to December 2018. At the time, as the Trump administration was ending exemptions for countries importing Iranian oil, Rouhani threatened that: “If one day they want to prevent the export of Iran’s oil, then no oil will be exported from the Persian Gulf.”

Because these threats to disrupt naval traffic in the strait have been long-standing, the United States and its closest allies have considered routinely the implications of Iran blocking of the Strait of Hormuz. Before and after the 1988 Operation Praying Mantis — wherein U.S. forces retaliated for Iran’s sea mining of the Persian Gulf and damage of an American ship — the U.S. intelligence community assessed such a scenario. To deter Iran from following through on its promise and to prepare for such a possibility, the United States and its allies have conducted multinational exercises as recently as last year focused on demining and contingency planning that goes back decades. But experts consistently have seen Iran’s complete closure of the waterway as “low probability.”

To be sure, it had been decades since Iran had targeted tankers and the exigencies of the time were different: In 1987, international oil tankers in the Persian Gulf became the target of both Tehran and Baghdad in what became known as the Tanker War, during the end of the eight-year bloody Iran-Iraq War (1980 to 1988). Since, the general consensus among Western strategists was that Iran wouldn’t follow through on the threats it has levied since the 1980s, as the costs of this course of action would almost certainly outweigh the benefits to Iran.

But Iran pushed the envelope in numerous ways in 2019 and 2020 in response to U.S. pressure. In just the last few months, Iran has again commenced dangerous naval provocations against U.S. vessels, tested new missile and possible submarine capabilities (during which it targeted mistakenly its own assets), and added to its arsenal of explosive fast boats, missile attack boats, and drone boats. Iran’s focus appears set on preparing for continued tensions — including in the naval domain — with the United States and its allies and partners. And if Donald Trump is re-elected, Iran’s leaders would have no choice but to buckle up for more sanctions and proceed with their plan to increase the cost of those sanctions until such time that a decision is made (in Tehran and in Washington) to engage diplomatically.

This is happening against a backdrop of the United States increasingly focused on great power competition and the Department of Defense and the services planning accordingly. Iran is mentioned in the 2018 National Defense Strategy and the 2017 National Security Strategy as a third-tier threat but America’s full range of advanced naval capabilities are shifting to the Pacific, not focused on Iran in the Persian Gulf. Because Iran had threatened to block the strait for years and due to the costs associated with the move for the regime, the United States hadn’t anticipated adequately the Iranian actions of 2019. Now, with Tehran’s initiative underway, Washington will be facing an Iranian naval threat in the Middle East even as it seeks to shift its attention away from the region.

Iran’s New Plan to Build Capacity on the Water

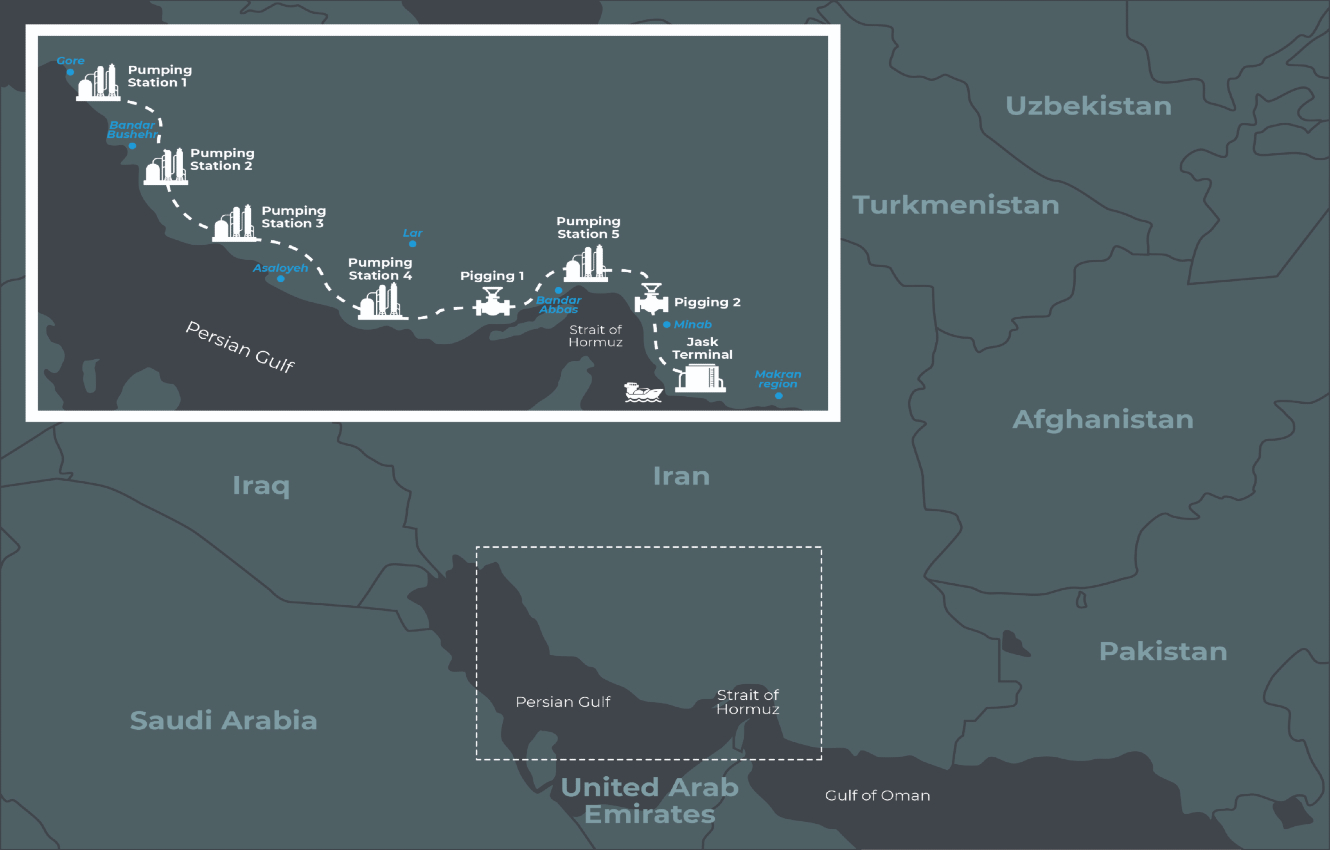

Tehran’s plan calls for operationalizing oil installations along the Gulf of Oman by early next year. Among the 17 different parts of this comprehensive plan, Iran is expanding its existing south-north gas pipelines with a dedicated line for oil. This line will run 1,000 kilometers along the southern coast of the country, from Bushehr to Bandar-e Jask, just east of the Strait of Hormuz. The southeastern province of Sistan-Balochestan, which runs along the Gulf of Oman, would become a key export hub. These steps would allow Iran to increase its energy production while freeing its hand to close the Strait of Hormuz if needed.

Source: War on the Rocks

Rouhani has indicated this plan will double Iran’s petrochemical production to $25 billion and allow the country to finally put its money where its mouth is: Closing the Strait of Hormuz won’t be an empty threat, but an actual contingency plan available to Iran at a lower cost, should it choose to implement it. Involving China in the development of parts of this initiative has another benefit for Iran. It would allow Iran to close the Strait while insulating China and without upsetting it, the Beijing support Tehran desperately needs. Rouhani noted that while Iran had often claimed that it was the protector of the Strait of Hormuz, it was the only country in the region whose oil exports still depended on the waterway as others had found other ways to augment their oil transfers through the Red Sea and other routes. For Rouhani, this plan is good politics: Its completion ahead of the 2021 presidential election would provide the Iranian president’s camp with a much-needed boost.

Implications for Renewed Provocation

Creating new routes for its oil exports may offer Iran escalatory options in the Strait of Hormuz. But would Iran take such a step? Such an Iranian naval offensive would represent a serious provocation — the most direct confrontation yet between Washington and Tehran. Some may question whether Iran would really choose to go this route. Hypothetically, we assume they may cite the resources necessary to build out Rouhani’s plan, at a time when Iran is under increasing economic pressure and facing political challenges in an upcoming domestic election cycle. Or the fact that the recent energy market crash coupled with the pandemic crisis make such an expensive undertaking not cost effective for Iran’s oil exporting program. While all are reasonable points for debate, these counter-arguments miss the point of Iran’s moves. Because the Strait of Hormuz plays both important practical and symbolic roles in the region, advancing Iranian capabilities to disrupt the waterway is a real deterrence tool, and a means by which to pressure neighbors as well as the United States and those aligned with it. The credible threat that Iran could shut down the strait now is backed by its increasingly effective and multi-layered arsenal of water and limpet mines, fast and attack boats, drone boats, anti-ship missiles, coastal defense, and submarines.

So, Iran may have increasing capabilities to conduct more aggressive operations in the strait. But who would risk making the decision to go ahead with it? On paper, the two Iranian navies still share the Strait of Hormuz as an area of responsibility. But in practice, the Guards have the upper hand there. And in addition to being better funded and equipped than the traditional Iranian navy, the Revolutionary Guards are also more aggressive than their conventional counterparts. The Revolutionary Guards navy will continue to employ an asymmetric doctrine when deciding how its naval assets are used. The objective is not naval superiority, but rather the bread and butter of the Guards’ operations: a mix of lower cost, sometimes proxy-executed, asymmetric tactics that can cause pain, sow concern, and build leverage.

Meanwhile, the U.S. Navy’s fleet of minesweepers is aging. As Pro Publica reported in 2019, “the sonar meant to detect mines was so imprecise that in training exercises it flagged dishwashers, crab traps and cars on the ocean floor as potential bombs.” The U.S. Navy has rightly prioritized increased readiness and force upgrades across the fleet. Recent budget cycles support that initiative but the debate over the what systems to upgrade and how much to invest is not over, the time horizon for the initiative is long, and a key focus remains on tools to address great power competition — specifically in the Pacific. The Navy’s serious undertaking is not aided by distractions from President Trump and his administration, commenting on naval rules of engagement, or what firms should build the Navy’s new frigates.

Finally, the uneven responses to Iranian provocations last year culminating in the killing of Guards Commander Qassem Soleimani have reinforced the unpredictability of U.S. staying power. All these elements likely factor into Iran’s calculus. Its new comprehensive initiative, which Supreme Leader Ayatollah Khamenei has characterized as the Rouhani government’s “most strategic plan,” might produce a new lever Iran may plan to use in its favor in the Persian Gulf.

Iran’s plan to set the conditions that would allow for effectively closing the Strait of Hormuz has been lost in a busy news cycle in the United States. But its implications, if implemented, are likely to reverberate for years to come, including drawing China further into the region. As the United States continues to send mixed signals about its strategy and presence in the Middle East and the U.S. Navy rightly continues to shift its attention and resources to the Pacific, Iran is building its capabilities and signaling its intention to consider adopting a more aggressive posture in the Persian Gulf and Gulf of Oman.

Without a clear and comprehensive strategy towards Iran in particular and the region in general, the United States risks perpetuating an “either/or” debate about its interests in the Middle East while not planning for and managing for evolving threats. Developing plans to assess Iran’s intentions in the Strait of Hormuz and wider Persian Gulf does not mean the United States, or its military, will become dragged deeper into the region. But effective management would begin by putting this development in the proper context of a pattern of escalation with Iran, isolation from allies on Iran policy, and the lack of any diplomatic efforts to de-escalate increasing tensions across the board with Iran. Without this broader analysis, diplomatic effort, and military planning combined, America’s Iran strategy will continue to fall short.

Elisa Catalano Ewers is an adjunct senior fellow at the Center for a New American Security (CNAS), on the adjunct faculty at Johns Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies, and a former U.S. government official.

Ariane Tabatabai is the Middle East Fellow at the Alliance for Securing Democracy at the German Marshall Fund, an adjunct senior research scholar at Columbia University, and the author of the forthcoming, No Conquest, No Defeat – Iran’s National Security Strategy.

Image: Wikicommons (Photo by Garshasbi.giti)