Join War on the Rocks and gain access to content trusted by policymakers, military leaders, and strategic thinkers worldwide.

What happens when the greatest threat to national security comes from a virus? What does that mean for defense spending, modernization, and civil-military relations? In Southeast Asia — where militaries have long had an outsized role in politics, economics, and society — the answers to these questions are still very much up for grabs.

There are over 54,000 confirmed cases of COVID-19 in Southeast Asia, with nearly 2,000 confirmed deaths. The evidence from Indonesia and the Philippines, which have very low levels of testing, suggests rates of infections and mortality could be much higher. While Malaysia appears to have flattened the curve, and Singapore is getting a handle on a massive outbreak in dormitories that house over 300,000 migrant workers and which account for 90 percent of the city-state’s cases, Indonesia and the Philippines are still struggling.

The pandemic will lead to a sharp economic downturn in the region, which will, in turn, result in shrinking defense budgets and declining arms imports. That is not necessarily a bad thing for regional security: austerity could force a rethink of defense priorities. However, the COVID-19 pandemic will also have repercussions for civil-military relations, likely setting back democracy even further as militaries securitize the pandemic, quell dissent, and put down popular unrest.

Battered Economies

The economies of Southeast Asia are in for a hard hit. No country in the region, save for Singapore, has sufficient capital for a large-scale stimulus program to bolster the region’s limited social safety nets. Every government is bracing for economic recessions and large budget deficits. Malaysia expects its economic growth in 2020 to contract by 5.9 percent, Thailand by 5.3 percent, Singapore by 4 percent, Indonesia by 2.5 percent and the Philippines by 1 percent. Only Vietnam is expected see positive, albeit slower growth, at 4.9 percent.

The pandemic and the looming global economic recession will negatively impact travel and tourism, which so many Southeast Asian economies depend on. China is coping with its own slowdown, a 6.8 percent contraction in first quarter GDP, with some estimates of 20 percent unemployment and massive decreases in exports. China will almost certainly buy less from Southeast Asia, invest less, and dispatch fewer tourists. A U.S. recession will have a similar impact.

Southeast Asian states will be coping with unemployment, food insecurity, and a decline in foreign investment and exports. The global economic downturn, coupled with a surge in anti-immigrant sentiment, will also have a major impact on the region’s migrant workers, whose remittances are so critical to their home states’ economies. That, in turn, will drive down domestic consumption. All of these developments will have knock-on effects on other sectors of the economy, including the banking, real estate, and service industries.

All governments are impatient to restart their economies, yet there is every concern that a premature re-opening will lead to second and third waves of the virus and prolonged pain.

This will also have an immediate impact on their security.

Flush Budgets

According to the Stockholm International peace Research Institute (SIPRI), Southeast Asia spent $34.5 billion on defense in 2019, a 4.2 percent increase from 2018. But SIPRI’s 2019 numbers don’t include full data for Myanmar or Vietnam, which adds at least $8 billion. Singapore topped regional defense spending at $11.2 billion, followed by Indonesia ($7.7 billion), Thailand ($7.3 billion), Malaysia ($3.8 billion), and the Philippines ($3.5 billion).

Figure 1: Defense Spending in Select Southeast Asian Countries (200-2019)

Source: Chart generated by the author using data from the SIPRI Military Expenditure Database.

Between 2018 and 2019, average defense spending in Association for Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) member states increased by 10.1 percent in nominal terms, from Indonesia (1.4 percent) to the Philippines (22 percent). And all countries, with the exception of Malaysia, whose defense budget fell 13 percent from 2015 to 2019, have seen very steady growth in defense expenditures over the past decade.

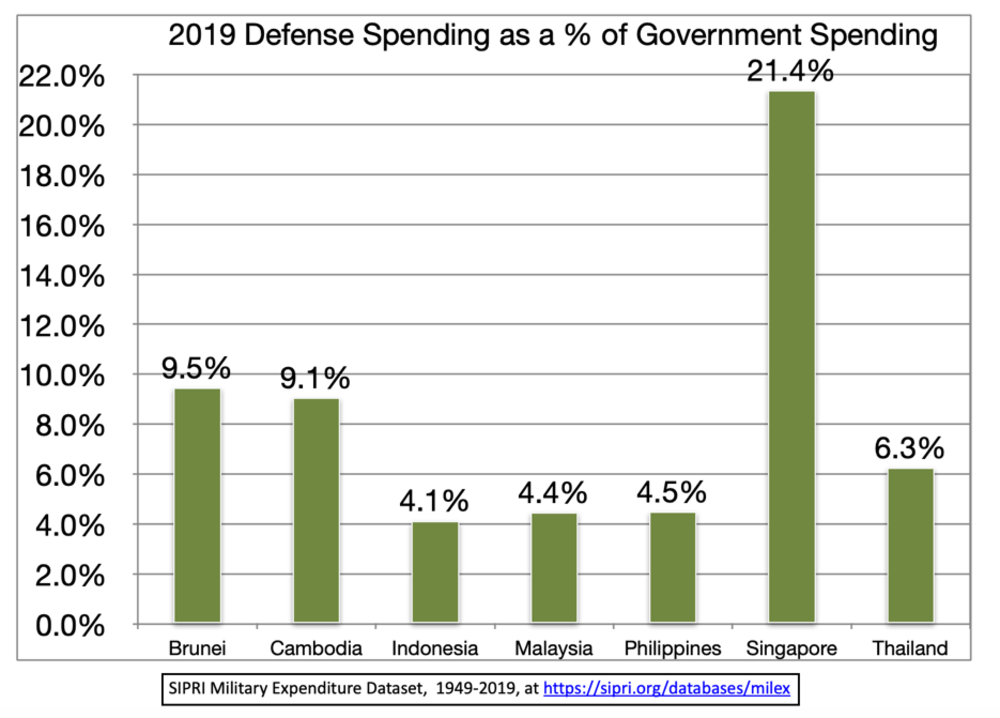

Figure 2: Defense Spending as a Percent of Government Spending in Select Southeast Asian Countries

Source: Chart generated by the author using data from the SIPRI Military Expenditure Database.

In Southeast Asia, governments have long tied defense spending to economic growth, in practice pegging defense within a specific range of share of the country’s overall GDP, with little annual variation. If the economy contracts, as it is likely to do during the pandemic, so will defense budgets.

The economic downturn will have immediate impacts on defense spending for the next few years in several states. It is inevitable that there will be further cuts in Malaysia, whose defense budget contracted in 2020. The Malaysian Armed Forces will offer little pushback, as they are arguably the least politicized in the region.

The Thai military, which actively backs the government that emerged following the 2014 coup d’état, saw its budget increase nearly 8 percent to $7.2 billion in 2020. Although it is being asked to make voluntary cutbacks of 10 percent, it is resisting additional cuts beyond ($555 million) already made.

Defense budget cuts in the Philippines and Indonesia will be particularly painful, as so much of military spending goes to personnel accounts (almost 80 percent of defense spending in the Philippines goes to salaries and pensions). While the Philippine Secretary of National Defense Delfin Lorenzana acknowledged that some of this year’s budget would be returned to the government, he stressed that “There are no projects to be sacrificed,” and that the government’s three-phase modernization program (2013-2028) would continue. The reality is that the armed forces in Manila and Jakarta are likely in for a few years of limited growth.

The one anomaly to this trend is Vietnam, which appears to have had an effective response to COVID-19. Despite a population of 96 million, a border with China, and significant cross-border flows, Vietnam has under 300 cases and not a single fatality to date. While some suspect that the authoritarian state with the most repressive media environment in Southeast Asia may be obfuscating the actual numbers, other evidence suggests that the data is sound. Vietnam has aggressively responded to the pandemic and as such is the first country to re-open its economy, which was already benefitting from the U.S.-China trade war.

Vietnam’s 2020 defense budget was just below $6 billion. Vietnam’s leaders are projecting a $7.9 billion defense budget by 2024. Unlike most of its neighbors, Hanoi earmarks a sizable portion of its defense budget — roughly 32 percent — for procurement. Vietnam is on course to having the third-largest defense budget in the region. From 2014-2018, Vietnam was the tenth-largest arms importer in the world, as it sought to bring power projection capabilities online quickly. Hanoi, which is locked in a territorial dispute with Beijing, is cognizant that despite China’s slowest economic growth in 44 years (expected 2.5 percent), its military spending is set to increase at roughly 6-7 percent in 2021, in line with past years for fears that not doing so would be perceived as a sign of weakness.

Threats: Perceived and Real

Pandemic-induced austerity may force Southeast Asian states to align their security spending with actual threats, not those conjured up by political and military elites to advance their institutional interests.

While some governments, such as the Philippines and Myanmar, remain beset by internal security challenges ongoing throughout the pandemic, the security situation is far less acute for most other states.

Several governments — like Vietnam or Cambodia — equate security with regime survival. Others see defense spending as a Veblen good, accoutrements for show. Thailand, for example has no real need for submarines (indeed the Gulf of Siam is too shallow to use them effectively), but Bangkok is buying three submarines from China because it does not want to fall behind its main rival, Vietnam. The Philippines has announced its intention to buy a submarine, though it has no relevant experience and can ill afford such a costly platform. Indonesia, an archipelago of 17,000 islands, has limited naval or coast guard capabilities, but continues to purchase and co-develop main battle tanks.

Without a doubt, some militaries have stepped in and played an important role in a pandemic response, yet others are being proactive for parochial reasons. We’ve already seen several militaries re-allocate their FY2020 budgets to COVID-19 responses. For example, in Thailand, where the government has called on all ministries to yield 10 percent of their 2020 budget to government coffers to combat COVID-19, the military made a 7.7 percent cut, but has refused any more, arguing that it has reallocated 33 percent of its budget toward public health efforts. However, the Royal Thai Army has not been transparent about its pledged reallocation, so some skepticism is called for.

In Indonesia, the military announced that it is directing a paltry 199 million Indonesian rupiah (US$13,100) for COVID-19 purposes. Of that 25.7 million rupiah will come from the military’s headquarters budget, 39.9 million from the army, 64.5 million from the navy and 69.5 million from the air force. Like the Royal Thai Army, the Indonesian armed forces are trying to repurpose funds within the military, rather than allocate them to other ministries, for example, by moving to reimburse military hospitals.

The Impact on Arms Imports

The impact of the pandemic on regional arms imports is already apparent. The Royal Thai Navy put the purchase of two Chinese-made submarines on hold, part of a $1.1 billion, three submarine deal. Likewise, the army has delayed a 4.5 billion baht ($139 million) purchase of 50 U.S.-made armored personnel carriers, though only after news of the procurement was leaked to the press. Indeed, the sale was going forward as late as April 20 despite the pandemic, demonstrating the military’s tone deafness. The Royal Thai Air Force slashed its budget by 20 percent, and has halted the purchase of two F-50 jet trainers from South Korea.

If the recession hits Vietnam, some imports (in particular long-range surface-to-air missiles) may be impacted. There is no evidence that big-ticket items for 2020, such as the $350 million deal to buy Yak-130 jet trainers from Russia, will be impacted. However, the country has done a very effective job in licensing foreign technology, including Molniya missile craft and a range of both short-range surface-to-air and URAN Switchblade anti-ship missiles, and Israeli small arms. The only exception to a cutback in imports would be Brahmos-hypersonic anti-ship cruise missiles, which Vietnam has been trying to import from India for years.

Indonesia, between 2014-18 the twelfth-largest arms importer in the world, is likely to see more modest acquisitions. Like Vietnam, Indonesia has tried to increase licensed production, especially of costly naval platforms. Jakarta is already reconsidering the import of three submarines from South Korea, a $1 billion deal it negotiated in 2019.

COVID-19 may force countries to shift resources from maritime platforms to army personnel. The militaries of Southeast Asia, even those of archipelagic nations like Indonesia and the Philippines, are dominated by their armies. Indeed, in most regional states the army accounts for a larger budget than the navy and air force combined, as internal security still dominates the strategic culture of most of the region’s militaries.

Civil-Military Relations in a Pandemic

The most important thing to monitor in Southeast Asia is not defense budgets or arms imports, but civil-military relations. A pandemic would stretch the resources of any state and invariably leads the military to step in to provide assistance in distributing aid, building quarantine shelters, providing logistical support, or even providing their medical staff and facilities to the general public. But in Thailand, the Philippines, and Indonesia the militaries are using the crisis to undermine democracy and the rule of law.

In Thailand, the military-backed regime has looked weak and out of touch. It was slow to respond, and quickly resorted to an emergency decree. The country’s low COVID-19 rates and fatalities are more due to its high-quality public health and medical preparedness, in spite of the government. Since the 2006 military coup, Thailand has become the most unequal society in the world. The pandemic exposed the economic precarity of the have-nots, who have not forgotten who has been in charge since 2006. Political opponents of the regime have proven to be far more responsive and politically adroit, a reminder that the military-installed regime lacks legitimacy. And yet, the Thai military’s instinctive response is to dig in its heels and use the crisis as an excuse to go after political dissent, while defending a monarch who has been AWOL during the pandemic.

Since the start of President Joko Widodo’s administration in 2014, the Indonesian military has been pushing to reassert itself in public life and civil administration, an initiative known as Bela Negara, meaning “Defending the Nation.” Though Bela Negara was largely the pet project of former Minister of Defense Ryamizard Ryacudu, the incumbent, Prabowo Subianto, has a similar agenda. President Widodo has already toyed with the passage of an emergency decree (as we’ve seen in Thailand, the Philippines, and Cambodia), but stepped back with a lesser “health emergency” decree. Widodo has looked to the military to backstop his government’s fumbling response. It has not helped that his Minister of Health, Terawan Putranto, is a lieutenant general in the army. Terawan has been anti-science and an indecisive leader during the pandemic, summoning the power of prayer. The president’s COVID-19 response team is dominated by current or retired generals and has few public health officials. Indeed, as Sana Jaffrey notes:

All personnel in charge of coordinating the crisis response are retired army officers. This includes the head of the disaster management task force, the national spokesman on the coronavirus crisis, the health minister, the religious minister, the minister of maritime affairs and investment, the defense minister, and the president’s chief of staff.

And the securitization of the COVID-19 response has led to a crackdown on civil liberties, including the arrest of 76 critics of the government. While a handful of defense industries are quickly trying to produce ventilators and the military has tried to distribute medical equipment, giving the Indonesian military greater power over civilian life and public policy is a setback for Indonesia’s fragile democracy. In an indication that the Indonesian government is looking for the military to play a greater role in COVID-19 response, the parliament recently approved a budgetary increase of IDR1.3 trillion ($87 million) to pay for military hospitals, the production of personal productive equipment in defense factories, and the deployment of medical and military personnel to combat COVID-19.

In the Philippines, President Rodrigo Duterte has called on the police and military to enforce a quarantine imposed under an emergency decree. He has continued his bluster about ordering police and military units to shoot anyone who violates quarantine, while also ordering the military to actively target the communist New People’s Army and its political fronts, whom he accuses of stealing aid. He has threatened to go a step further and declare martial law, saying that he “might declare martial law and there will be no turning back.” To date, the military has been mute on the subject. The Philippine army has push back against Duterte before, in particular his cozying up to China, broadsides against the United States, and his abrogation of the Visiting Forces Agreement.

Duterte, who has actively targeted media institutions, has used the pandemic to try to muzzle them. The Senate struck out a provision n COVID-19 response legislation that would allow the president take over broadcasters; he nonetheless shut the largest down. While such threats to impose martial law go back to the start of his administration in 2016, Duterte’s declaration of martial law in parts of Mindanao during the Marawi siege was only lifted in December 2019. As the case in Indonesia, almost all people responsible for handling the pandemic are active duty or retired senior-level military personnel. Many fear that the COVID-19 pandemic is finally the nationwide crisis Duterte needs to declare martial law, suspend democratic institutions, and shut down the free press.

The Vietnam People’s Army played a low-key but important role in quickly establishing mass quarantine centers and assisting in testing in support of government efforts. Military doctors and technicians have come up with important innovations, while military-owned companies have increased production of ventilators and other personal protective equipment. The military never had the lead or sought to enhance its power. The Vietnam People’s Army is a party-army, and firmly under the control of the communist party. As in China, the military is constitutionally bound to defend the party, not the state. But the army enjoys a high degree of popular legitimacy due to its role in winning independence, unifying the country, and pushing back against Chinese aggression. And the government’s quick and decisive response to the pandemic has enhanced its own popular standing, important for the regime as it heads into its 13th Party Congress in early 2021.

The militaries have largely been in charge of the pandemic response in Thailand, the Philippines, and Indonesia. In part, the civilian governments have been complicit in this, trying to make up for weak governance. And none of the militaries that have assumed key pandemic roles have handled the crisis well — in Indonesia and the Philippines, it’s getting decidedly worse. Indeed, the countries with the best response and highest rates of testing and social compliance have been Malaysia and Vietnam, which have relied on their militaries only to run large quarantine centers or augment the police to enforce shelter-in-place orders, but have been out of the decision-making chain.

Looking Ahead

The COVID-19 pandemic is far from over, and until a vaccine is developed, countries need to anticipate second and third waves. This will have a major impact on economies throughout Southeast Asia, which in turn should have an impact on defense budgets. That might not be a bad thing: many countries have imported costly platforms they do not need. Indeed, shrinking budgets could refocus the ways and means on actual threats, rather than those conjured by political and military elites. Yet, the greatest impact of COVID-19 on regional security will be in the domain of civil-military relations. Weak governance has given space to militaries to assert themselves, often with the encouragement of weak or authoritarian-minded political leaders.

If the COVID-19 crisis persists, militaries in Southeast Asia will likely be called upon to enforce quarantines in countries with high rates of poverty and little in the way of social safety nets. The Philippines and Indonesia are both food insecure, and rely on imports of rice and other commodities which are increasing in price as other countries curb exports. Beyond existing, worrisome trends towards a greater military role in domestic society and politics, then, the potential for quashing mass unrest driven by food insecurity looms large as an additional threat to civilian governance.

Zachary Abuza is a professor at the National War College, Washington, DC and an adjunct at Georgetown University’s Security Studies Program. The views are his personal opinions and do not reflect the opinions of the National War College or the U.S. Department of Defense.