The Challenge of Boko Haram Defectors in Chad

Last September, I spent two weeks in Chad. Everyone I spoke to — government officials, average citizens, religious leaders, former fighters, activists, and aid workers — kept bringing up a topic they felt was key to the future of the country: the urgent need to properly “manage” returning Boko Haram fighters and their families. The issue is fraught, and raises a number of difficult questions about how to approach the problem. What should rehabilitation programs entail? Who will coordinate them, and who gets to participate? And where will the funding come from?

These are all questions that the government of Chad will need to grapple with. But in the context of the most recent attacks across the Lake Chad sub-region — in which hundreds of people including soldiers were killed — the most important question is how to assure communities that former fighters have been successfully rehabilitated. The issue is increasingly urgent, with residents and local experts expressing concern that the recent upsurge in Boko Haram attacks is due in part to former fighters returning to the group. After an attack in March that killed nearly 100 soldiers, the deadliest terrorist attack in Chad’s history, concerns about recidivism are likely to grow.

The government of Chad should define a clear policy for rehabilitating and reintegrating former Boko Haram fighters and their families into society. Such a step is crucial to prevent an unending cycle of violence in a country that has already witnessed decades of civil conflicts before Boko Haram’s violence. Moreover, the mental health needs of former fighters need to be addressed, both for their own merits, but also to protect their children from transgenerational trauma. This must be a part of wider program of community healing, and requires a clear legal framework that outlines the conditions for eligibility and terms of reference for supported programs and devolves responsibility for implementation and funding to the community level.

Chad does not need to start from scratch; there are promising local initiatives for the reintegration of ex-fighters upon which it can build. Often led by Chadians, these projects leverage modest resources to encourage disengagement, manage trauma, and rebuild trust. The Chadian government can also glean certain lessons from around the region including from Nigeria, a neighbor that has been running a program for defectors with similar grievances and experiences for years. Having interviewed defectors from Boko Haram in Nigeria — and examined the country’s program to reintegrate them back into society — it is clear that the circumstances in Chad, though similar to Nigeria, are unique and require a tailored approach.

Chad’s Fight Against Boko Haram

Boko Haram formed in 2003 in the northeast Nigerian town of Maiduguri under the leadership of its founder, Muhammad Yusuf. Its goal was to overthrow the Nigerian state and establish an Islamic “caliphate.” Yusuf used extremist interpretations of Islam to question the legitimacy of Nigeria’s secular government and Western-style institutions (e.g. schools and universities) and to justify acts of violence against political, military, and civilian targets, including dissenting Muslims. Boko Haram, which literally translates from Hausa as “Western-style education is Islamically forbidden,” became the deadliest Islamist group in 2015. The group’s violence was at first mainly aimed at Nigeria, but expanded from early 2014 to become a regional campaign with attacks on civilian and military positions in northern Cameroon, southern Niger, and western Chad. Since 2009, the group’s campaign has killed an estimated 30,000 people, displaced over 2.5 million, and exacerbated a complex humanitarian crisis in the Lake Chad sub-region. Chad became a primary target after it changed its neutral stance on the group in 2015 by accepting Nigeria’s invitation to join the war against the group.

Nigeria has been fighting Boko Haram since 2009. Chad, Cameroon, Niger, and Benin came actively onboard in 2015 through the Multi-National Joint Task Force (MNJTF), a coalition of units, mostly military, headquartered in N’Djamena and with a mandate to end Boko Haram’s insurgency. With technical support from Western countries, the joint task force has had some success against Boko Haram. Between 2015 and 2016, Boko Haram’s self-declared caliphate, which stretched across Nigerian territory roughly the size of Belgium, was dismantled. In addition, an estimated 5,000–7,000 fighters splintered into two factions and were pushed to the fringes of Lake Chad, a vast marshy body of water dotted with islets sitting between Nigeria, Niger, Cameroon, and Chad.

At the same time, the brutal actions of some MNJTF troops alienated many young people, pushing them into the arms of Boko Haram. A UN Development Programme study on the paths to violent extremism in Africa found that 71 percent of its respondents identified extra-judicial killing of family or friends and illegal arrest and retention by security forces as the tipping point for their joining Boko Haram or al-Shabaab, another violent extremist group operating in East Africa. Boko Haram recently regained momentum and has been launching attacks with increasing sophistication and efficiency.

March 2020 marked a defining moment in Chad’s war against Boko Haram. Following the deadly Boko Haram attack on March 23, the country launched a military operation codenamed “Operation Wrath of Boma” — Boma being the peninsula where the seven-hour long assault took place. It was the deadliest incident in Chad’s battle with Boko Haram to date. The offensive was personally coordinated on the ground by President Idriss Déby, Chad’s military dictator, who came to power in 1990 and is in his fifth term of office. Boko Haram is just another in a long list of problems, including political violence, corruption, and extreme poverty, that threaten Déby’s brittle regime, but it is currently the most serious of them all.

On the Ground in Chad

Back in September when I visited Chad, the debate on Boko Haram was focussed on the reintegration of former members. Joblessness and the continued attacks from Boko Haram left Chadian defectors of the group frustrated and on the brink of re-joining the group. That was the mood I picked up on during conversations with six former Boko Haram members — men and women — in Bol, western Chad. One man, Duna Lamba, joined Boko Haram in 2014 when the group was finding its strength and first proclaimed the establishment of an Islamic state. Along with several thousand other Chadians, he abandoned his home, renounced his Chadian identity, and joined Boko Haram’s “caliphate.” Duna had fought for two years when N’Djamena announced an amnesty, creating a pathway for fighters to leave the group and return to Chad. The group had suffered a number of setbacks following a campaign by the MNJTF, including having its food and arms supply routes constricted. Along with more than 2,000 others, he seized N’Djamena’s olive branch and left.

By one estimate, there are currently 2,200 former Boko Haram fighters in Chad. Upon turning themselves in to the authorities, some of these fighters were reportedly first held in an internment camp before they were released following accusations of human rights violations against Chadian authorities.

Former fighters first lived in settlements near the islands of western Chad where Boko Haram continues to wreak havoc, and then moved to a nearby village following a string of attacks against them. Duna and his family, as well as the others I interviewed, now live on the outskirts of Medi Koura in one of the largest enclaves of former fighters, which is home to approximately 1,200 former Boko haram members (including an estimated 300 women, some the widows of killed fighters, and about 500 children). They feel let down by the government. “They promised to help us to rebuild our lives but almost two years after our return, no one has done anything to help us,” said Duna. Most former fighters lost everything they had when they left to join Boko Haram. They claim that, before joining the group, they used to be farmers in rainy seasons and fished in Lake Chad or engaged in petty trading in dry ones. After defecting, they learned that their villages were amongst those targeted by the group. “We now have no businesses to run, no work to do, no farms to cultivate,” Modu, a former fighter in his early thirties, complained.

For many former fighters, the only alternative to rebuilding their lives is re-joining Boko Haram. “About half of those we came out with have gone back to the bush [referring the territory from where Boko Haram operates] after getting tired of waiting for help,” said Abakar who also fought with Boko Haram. “We were up to 4,000 three years ago. We are now not more than 2,000,” another one added, noting the number of former defectors that have re-joined the group. While this is difficult to verify, it is only logical that some disillusioned defectors may not have too many options. Given the limited opportunities in the area and their low level of education, it is hard, if not impossible, to re-start life without some sort of intervention. Defectors also speak of a lack of basic infrastructure. There are no schools or healthcare facilities for the 500 children of the former fighters. On top of this, they face relentless attacks by Boko Haram who view them as traitors. They were attacked twice in 2018 by suicide bombers in their former settlement. Despite several fatalities and injuries, these incidents did not get media attention, in part because there are no media representatives in the most remote and unstable areas of Lake Chad. These attacks are partly why they relocated to their current commune.

What Drives Boko Haram Recruitment in Chad?

There are perhaps as many reasons and motivations for joining violent extremist movements as there are fighters and no single factor that can account for an individual’s decision to join. Chadian fighters are not different, but a warped interpretation of Islam, illiteracy, poverty, and inequality, and a sense grievance, genuine or imagined, appear to be the main reasons why Chadians have joined Boko Haram.

Former fighters say they joined for ideological reasons to help Boko Haram achieve the objectives articulated by Yusuf, and they believe God will reward them for partaking in this cause, However, that is not the only reason, and the Chadian government can take steps to address other drivers such as poverty and a lack of opportunities. Roughly 13 percent of the respondents in the UN Development Programme study referenced above who voluntarily joined Boko Haram or al-Shabaab identified “employment opportunities” as their reason for joining. This represents the third most frequent response, the first and second were “being part of something bigger” and “religious ideas.” The report observed that while poverty alone is not enough to explain violent extremism in Africa, Boko Haram and others piggyback on perceptions of disproportionate economic hardship or exclusion due to religious or ethnic identity to recruit and radicalize young people. If these grievances — some of which are real — are not tackled, they will continue to be weaponized by violent extremist or criminal groups. African governments and their partners must address these real grievances and provide viable alternative pathways not only for former fighters, but also the society at large.

Although former fighters in Chad live without the threat of violent retaliation from communities, it is still essential to rehabilitate and reintegrate them. Dimouya Souapebe, the Secretary General of the Lake Chad regional government, perhaps articulates it best: “We need to change these people’s way of life… We need to reset their relationship with government.”

Dimouya feels strongly that shortcomings by governments across the Lake Chad region have contributed to making thousands vulnerable to groups like Boko Haram in the first place — namely through a lack of educational and employment opportunities. Dimouya is right. Several credible studies show that poverty and ignorance have played a part in Boko Haram’s recruitment and radicalization. The UN Development Programme found that most of its respondents who voluntarily joined Boko Haram or al-Shabaab had little or no secular education. The study also found that 57 percent of the respondents admitted to not being able to read or understand the Qur’an, the key religious text exploited by Boko Haram and other self-proclaimed jihadi groups. In Chad, only 50 of the 2,200 former Boko Haram fighters have been to primary school — and not all of them can read and write according to the Centre for Development Studies and the Prevention of Extremism.

Improved education and skills training appear to reduce the likelihood of Chadians joining violent groups. For instance, the UN Development Programme discovered that “a person who received at least six years of religious schooling is less likely to join an extremist organization by as much as 32 percent.” Similarly, researchers from Yale and Princeton, working with Mercy Corps, tested the impact of economic interventions and cash transfers on 1,590 beneficiaries in Afghanistan. They found that while neither vocational training nor the cash transfers alone had lasting effects on attitudes towards violence, the combination of both led to a large reduction in participants’ willingness to support opposition armed groups.

Duna and his friends’ questions at the end of my interview were pretty revealing in this respect. Their questions focused on employment opportunities in Europe, the pay, whether they are likely to get jobs, and the possibility of migrating. This is an indication that employment opportunities played a significant role in their recruitment into Boko Haram. It also shows that a rehabilitation program that includes employment skills such as literacy, civic education, and vocational skills, matched with work opportunities, has a fair chance of contributing towards community healing in the Lake Chad region.

Religious ideology is an important pull factor and must be tackled through credible interventions. Alongside poverty and illiteracy, Chad should confront the unique religious narrative upon which Boko Haram thrives. Boko Haram uses elements of Islamic teachings to recruit and radicalize young people and to justify its violence. It rejects secularism, democracy, and western-style education, which it considers to be both incompatible with Islamic values and hostile towards Muslims. The group seeks to supplant these systems with its version of Islamic ones. Former fighters who have rejected Boko Haram do not necessarily reject these views once they’ve left the group.

A program to rehabilitate former Boko Haram fighters should include imams to work with former fighters that provide a valid, alternative world view based on mainstream interpretations of Islamic scripture and doctrines. The religious leaders will need to be trained by experts on Boko Haram and other jihadi groups to understand how Boko Haram misuses scripture, the pillars of the group’s ideology, and how best to dismantle it. Imams and other experts that have experience deradicalizing extremists in other countries would be a useful source of expertise in designing such a program and training potential Chadian facilitators.

Trauma and Mental Health

Chad should help fighters deal with the trauma they have experienced. A significant percentage of these fighters have become addicted to tramadol, an opioid pain medication that they took in their bid to stay energic to fight. Women members have suffered rape and sexual abuse at the hands male members, and children have witnessed and participated in violence and seen aerial bombardments, leading some to lose limbs. Some have reportedly been subjected to torture and dehumanizing treatment by security forces. Two years after quitting Boko Haram, some former fighters still have flashbacks and nightmares. Having witnessed and participated in large-scale violence, suffered abuses, and/or become addicted to drugs, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and other mental health issues are rife and need to be treated. Psychologists, drug experts, social workers and professionals can help with this.

Beyond the former fighters themselves, this treatment will also ensure better life opportunities for their children, which number in the thousands. Experts warn that growing up with parents suffering from PTSD can damage children’s physical and mental health. Given the scale of this issue in Chad, rehabilitation and reintegration go far beyond the family unit and will help community healing and cohesion, which are fundamental to building a sustainable peace. One potential intervention is psychospiritual therapy. This is a method by which imams and psychologists in Nigeria’s deradicalization program (discussed below) work together to treat individuals with mental health issues that are mixed with elements of religious ideology by drawing on surrounding divine forgiveness and the possibility of redemption.

Lessons from Nigeria

Chad should learn from Nigeria’s rehabilitation program, but a wholesale importation will not work.

To learn lessons from Nigeria, a Chadian government delegation visited Nigeria’s Operation Safe Corridor, a government facility that is deradicalizing and reintegrating “low risk” former Boko Haram fighters. Youssef Mbodou Mbami, Chad’s former ambassador to Niger and Nigeria and now a traditional leader for the Bol region, was on the delegation. He speaks highly of the Nigerian model and indicates that N’Djamena is exploring ways to replicate it.

The rehabilitation program in Nigeria works with an interdisciplinary team of about 180 experts that include imams, psychologists, doctors, teachers, drug experts, social workers, artists, and interpreters. They work to tackle three inter-related aspects of radicalization: countering Boko Haram’s ideology; mitigating the socio-political grievances that facilitate recruitment; and providing mental health support for ex-fighters. Operation Safe Corridor seeks to do this by highlighting Islamic texts in a way that promotes peaceful coexistence and counters Boko Haram’s ideology; teaching numeracy, literacy, vocational skills, and sports; and helping with trauma and drug addiction issues. Chad can learn from both Nigeria’s successes with this program, but also its challenges.

Operation Safe Corridor faces important obstacles. It is run by the Nigerian military, is extremely expensive, some participants have been treated unequally, and it is unclear if there is a legal basis in the Nigerian legal system for rehabilitating former fighters. One of the main limitations of the Operation Safe Corridor is that it is run by the Nigerian military. The armed forces have a negative reputation in Nigeria, and the military kept aspects of the initiative shrouded in secrecy, citing security concerns, some of which may have some legitimacy. As a result, the initiative is struggling to encourage communities to accept former fighters, in part because societies are not convinced about the effectiveness of the scheme. This scepticism was particularly apparent on social media recently following a recent escalation of Boko Haram attacks.

Furthermore, Operation Safe Corridor is also extremely expensive because of the large number of experts and security personnel involved, all of which need accommodation and maintenance allowances in addition to monthly salaries. Thirdly, its scope is limited as it does not treat women and treats teenagers on the same basis as adults. Finally, there are fundamental questions about the army’s legal basis to “forgive” former fighters and run the program. These are pitfalls Chad should carefully consider.

Conditions for Reintegration Are More Promising in Chad Than in Nigeria

Fortunately, former Boko Haram fighters in Chad do not face the level of physical threats as their Nigerian counterparts. Unlike in Nigeria, where deserters suffer stigmas and death threats from the communities they return to, the situation is very different in Chad. In Nigeria, residents have been deeply resistant to accepting former fighters back into communities, including those who have been rehabilitated, with some locals threatening to kill them if released. By contrast, in Chad, defectors live side-by-side with other residents without fear of physical violence.

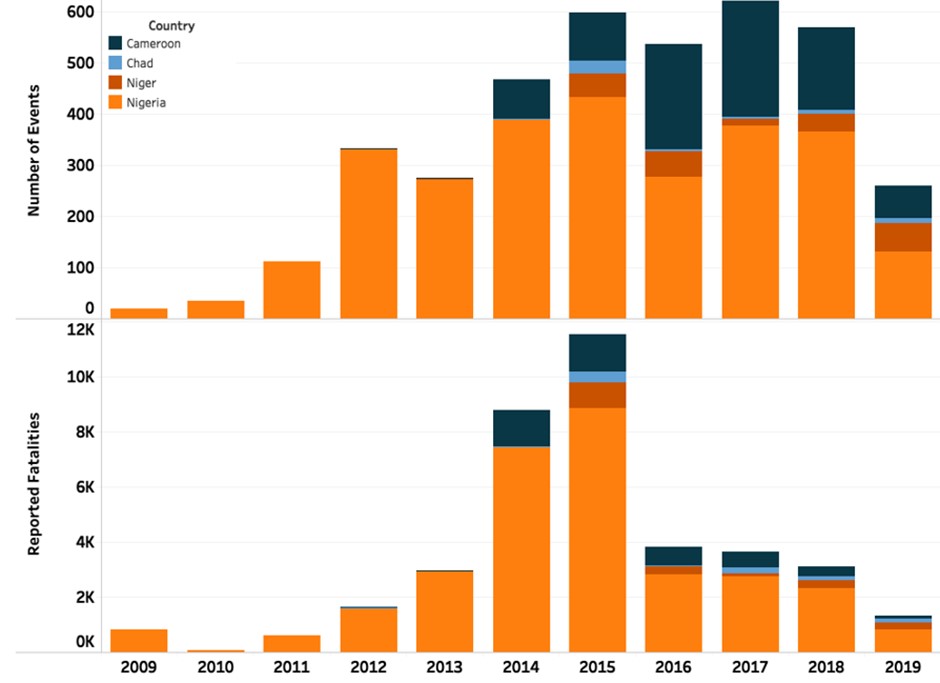

That Chadian fighters mostly fought in Nigeria and primarily destroyed communities other than their own could be a significant explanation. Nigerian fighters destroyed their own communities, with some killing their acquaintances, family, or friends. Although Boko Haram first attacked Chad in 2012, the country did not become the group’s deliberate target until 2015, when N’Djamena changed its neutral stance on the group by joining Nigeria’s campaign. Only then did Chad see the first attacks on its capital and an escalation of violence on its side of the Lake Chad border. Despite that, in the past decade, over 70 percent of attacks and 80 percent of fatalities were in Nigeria. The remaining were distributed between Niger, Cameroon, and Chad, with Chad being the least impacted.

Figure 1: Violent Events and Reported Fatalities Involving Boko Haram by Country and Year (Jan. 1, 2009 – May 11, 2019).

Source: Hilary Matfess generated from ACLED.

However, this may not be the only reason behind these differing attitudes. Chad’s militia fighting Boko Haram, comites de vigilance, is not as strong as Nigeria’s civilian joint task force, which has been combatting Boko Haram for six years and has lost hundreds of members. It takes the lead in coordinating communal resistance to the reintegration of Boko Haram fighters in Nigeria. Part of the reason for the lack of community resistance in Chad could be the absence of an organized group to carry it out.

Furthermore, unlike large Nigerian cities like Baga, Monguno, and Bama that were completely destroyed by Boko Haram, most of the communities dislodged in Chad are small villages on the fringes of the country. Survivors simply do not have the capacity to mobilize around any resentment felt towards former fighters. Finally, unlike Nigeria where the legal and customary authority of traditional rulers such as emirs has weakened in the past six decades since independence, traditional institutions in Chad under the Chef de Canton still exercise limited governmental powers and command significant respect from communities. In Chad, these leaders have backed the government’s call for amnesty and the reintegration of former fighters. In short, while there may be stigma and resentment at former fighters returning to their communities in Chad, there is not currently the will or capacity to mobilize this into violent action.

What Chad Should Do

Chad should adapt Nigeria’s three-pronged approach and its use of experts from across multiple disciplines. However, rehabilitation programs should be run and managed by civilians, not the military. It is plausible, and could in fact be better, to develop a community-based model to support reintegration. Programs could build community centers to bring ex-fighters, survivors, and community members together. Such a program should have clearly defined objectives and measurement indicators in place and be subject to independent evaluation. It should run transparently while recognizing the real security risks of attacks from Boko Haram. To start, the Chadian government can build on the lessons learned from local initiatives seeking to support reintegration by young Chadians.

In addition, the government should support existing local initiatives that show promise in preventing recidivism and address the emotional trauma of former Boko Haram fighters. There are several initiatives run by young residents in western Chad to facilitate defections, heal trauma, and help reintegration of former fighters. A youth-led local radio station, Kadaye (“a traditional canoe” in the Buduma language), encourages defection from Boko Haram and promotes peace and social cohesion through talk shows, dramas, news programmes, testimonials, and storytelling in major local languages — Buduma, Kanembu, French, and the local dialect of Arabic. The station was so effective that Boko Haram felt threatened by it. According to its director Adam Tchari, it was warned and then targeted by the militia in an intercepted attack in 2014. Similarly, Iyal Hille (“Children of the Town” in local Arabic), a theater club, produces plays that discourage young people from joining Boko Haram and encourages generosity towards survivors. The theater performs street dramas in markets, village squares, and similar places and produce short films that are shared through social media. Radio and theater have proven their capacity to play a significant role in healing conflict-scarred societies, such as in Liberia, where journalists and artists contributed to the country’s post-civil war recovery. With the right resources, radio stations like Kadaye and theatre clubs like Iyal Hille have the potential to support healing and community cohesion not just in Chad, but across the Lake Chad region. Kadaye and Iyal Hille were previously funded by the U.S. Agency for International Development, but funding has now been cut.

A similar approach is used by Taige Ahmed, a professional dancer and choreographer who promotes healing and reintegration through movement and rhythm-based techniques, as part of a bespoke methodology known as Pas ev Avant, developed with his company, Association Ndamsena. Ndamsena has an extensive track record of sensitization and community building work inside refugee camps in Southern Chad, conducted over the last twelve years with support from the U.N. Refugee Agency. Taigue works with survivors and defectors to heal trauma through movement and dance. These types of approaches to trauma healing have been validated through expert studies. Taigue says the aim of his pedagogy is simple: to bring a smile back to refugees who have suffered years of horror. Having participated in and observed one of Taigue’s sessions, I can see the potential of his method to help people recover from trauma. People who do not speak the same language are able to communicate and laugh using movements and gestures.

Conclusion

In recent years, thousands of Chadians have defected from Boko Haram. What they find in Chad upon their return is not promising. Many defectors cannot find work or a new, positive purpose to their lives. A sense of aimlessness, combined with attacks from their former group, leaves them frustrated and bewildered. Many have likely returned to Boko Haram and more could follow suit if they are not properly reintegrated back into the community. What is more, their children could suffer transgenerational trauma, grow up without an education, and end up with similar choices as their parents, if not worse. The cycle of poverty, radicalization, and crime could continue.

The only viable option for Chad is to implement a scheme to rehabilitate and reintegrate former fighters and their families. This program should adapt Nigeria’s three-legged approach of working with a diverse collection of experts to counter violent religious ideology, teach skills, and treat mental health and drug issues. Small-scale local initiatives in Chad are a good place from which to build. But to stand a chance, a program for defectors must be a part of a wider community healing and rehabilitation effort. There is an expressed desire on the part of the government to start something, but the devil is in the details. Western countries and partners helping national governments to fight Boko Haram should consider supporting Chad with technical expertise and financial resources to treat and reintegrate Duna and his former colleagues-in-arms. The problem of reintegrating former Boko Haram fighters into society is not going away.

Bulama Bukarti is an analyst specializing on extremist groups in sub-Saharan Africa at the Tony Blair Institute for Global Change in London. He has researched Boko Haram in his native Nigeria for a decade and is now pursuing a PhD on the subject at SOAS, University of London. He taught law at Bayero University Kano and practiced as a human rights lawyer and anti-corruption advocate in Nigeria for half a decade.

Where relevant, names have been changed to protect the confidentiality of individuals. Approval of Chadian authorities was obtained before interviews.

Image: U.S. Navy (Photo by Mass Communication Specialist Second Class Evan Parker)