Of Course the U.S. Military Has A White Supremacy Problem. It’s Baked In.

What was the reason that induced Georgia to take the step of secession? This reason may be summed up in one single proposition. It was a conviction, a deep conviction on the part of Georgia, that a separation from the North-was the only thing that could prevent the abolition of her slavery.

– From a speech to the Virginia Secession Convention by a delegate from the Georgia secession convention, Henry L. Benning, 1861

Imagine that you’re a young recruit. You have enlisted in the U.S. Army, and the Army has granted your wish, going so far as to guarantee you the military occupational specialty of your choice — 11X, infantryman. You’re going to follow in the footsteps of a long line of soldiers going back more than 200 years to the Continental Army, a force initially made up almost entirely of riflemen, with a smattering of artillery. Upon induction, you are selected to go to Fort Benning. Having completed basic training, you move across post to attend the Army’s infantry school, emerging as a newly minted infantryman. Now imagine that your name is Pvt. Tyler Washington, and you’re African American. You have spent all of your initial training in the U.S. Army at a base named after a southern secessionist, a member of Georgia’s delegation to the Virginia Secession Convention, and a man who never served in the U.S. Army, only against it. A man who fought for the right to keep people as property — people who looked like you — and who himself owned 89 other human beings. A man who served a cause that was antithetical to what the U.S. Army stood for, even then, and even more so now.

The Department of Defense is under pressure from Congress to expose and correct its white supremacy problem. It’s clear that there is a problem — one not confined to the Army — and a recent troop survey indicates a worrying upward trend in signs of white supremacy in the ranks. But it’s also clear that the department has taken a softball approach to the challenge — as illustrated by the fact that it doesn’t treat membership in white supremacist organizations as a sole rationale for discharge. Worse yet, the services, especially the U.S. Army, have a long habit of venerating those who fought for the Confederacy, both ex-Army oath-breakers like Col. Robert E. Lee and those who never served in the U.S. Army, like Henry L. Benning, whose major relationship to the U.S. Army was that they fought against it. Might one wonder why the services have a poor record combating white supremacy? Maybe it’s because white supremacy is baked in.

All persons born or naturalized in the United States and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and of the State wherein they reside. No State shall make or enforce any law which shall abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States; nor shall any State deprive any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law; nor deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.

–14th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, Section 1

Monuments to White Supremacy

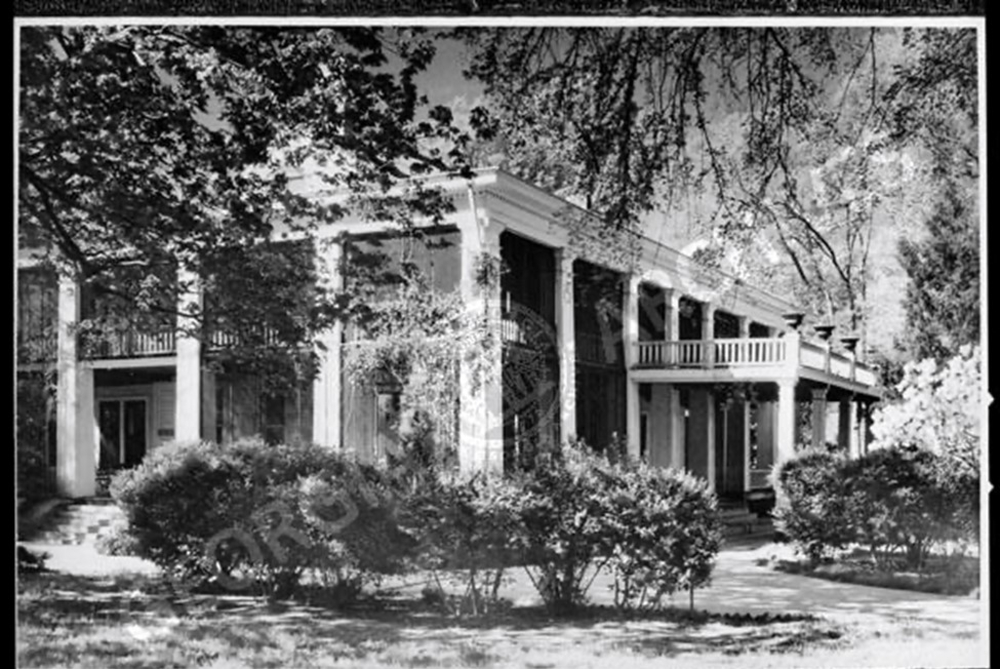

The Army has a peculiar attachment to its Civil War-era symbols of treason, generally in the name of military heritage. But to our fictional Pvt. Washington, just graduated from infantry school? They’re not part of his military heritage, except as a foe to be defeated a century and a half ago. This young soldier joined the U.S. Army, not the Army of Northern Virginia — which he could never have joined in any case. The naming of U.S. Army bases after Confederate generals is a legacy of the Jim Crow era, not a legacy of the Civil War. Camp Benning, established in 1919, was built on a plantation. The camp commander lives in the former plantation house. It was named after a Confederate general at the suggestion of local dignitaries, more than half a century after the Union won the Civil War. Arguably, it would have been difficult (but not impossible) to find an individual more antithetical to the Army’s values or the officer’s oath of office. It wasn’t the first Army base to be named after a Confederate general, nor the last.

Figure 1: The Plantation House at Camp Benning (1944).

Source: Photo from Georgia Archives.

It’s no accident that all of the U.S. Army’s Confederate namesake bases are in states that made war on the Union, and that resisted civil rights for their citizens of color for more than a century after Lee signed surrender documents at Appomattox. The Army’s acquiescence to base names inspired by the South’s racist legacy was an artifact of the 20th century, not the 19th. All of them were named between 1917 and 1942, in a period when the South strongly (and successfully) maintained racial segregation, as if the Confederate states were the victors. Camp Bragg (now Fort Bragg) was named in 1918 after an officer who resigned from the Army in 1856 to become a plantation slaveowner, and later became a staggeringly incompetent Confederate general. Camp Beauregard was named in 1917. Camp Lee was built in 1917 and rebuilt in 1940. Fort A.P. Hill was established in 1940. Fort Polk, Fort Gordon, and Fort Pickett were built in 1941, Fort Rucker and Fort Hood in 1942. All of these forts were named during a period when the military itself was still segregated. The fact that the U.S. Army continues to defend the naming of bases, buildings, and facilities after Confederate officers makes clear that combating white supremacy in the ranks is simply not a priority for the Army, despite protestations to the contrary.

Any army which so vehemently defends a legacy steeped in overt racism is not taking the problem of white supremacy seriously. But it’s not the only service with a problem. The U.S. Navy avoids the base-naming problem because it names bases after their locations: Pensacola, Norfolk, Great Lakes. But it has its own way of memorializing a racist legacy. The U.S. Navy has 11 fleet carriers — the most powerful surface vessels ever floated and a uniquely American symbol of power projection. They are named mostly after presidents, including Abraham Lincoln, who led a Union that strove to abolish slavery, and Harry Truman, who ordered the U.S. military to desegregate. The lead ship of the largest carrier class is named after Adm. Chester Nimitz.

Figure 2: African American Soldiers (presumably of the 555th Parachute Infantry Regiment) preparing for a qualifying jump, Fort Benning, March 1944.

Source: Photo from National Archives.

And two carriers are named after United States legislators, both from the South, and both unrepentant segregationists. Sen. John C. Stennis of Mississippi and Rep. Carl Vinson of Georgia were both signatories of the 1956 Southern Manifesto, written to oppose the integration of public places, especially schools. Vinson was a strong supporter of the U.S. Navy over a 50-year career, but was “no friend of civil rights legislation.” Stennis accumulated a voting record solidly in opposition to civil rights, if highly favorable to defense. With a legion of opportunities to name carriers after other worthy Americans, the Navy has two carriers named after staunch white supremacists.

The messages sent to soldiers and sailors by maintaining monuments to racism are pernicious, and unavoidable. The first message, and the most dangerous, is that not only is it OK to support a white supremacist cause, but that it’s OK to take up arms to do so. This is the kind of message that the Army, and by extension the Department of Defense, needs to counter, and counter decisively and with finality. The second message is complementary and aimed at soldiers and sailors of color — that the Army and Navy will prioritize the preferences of modern racists and long-dead rebels over the individuals that make up an integrated force. This is a message that I’m certain many soldiers and sailors will simply shrug off — but that they should never have had to. I cringe at the idea of a (mostly white) officer corps who not only think the lionization of rebels and traitors who shed Union blood for an unjust cause is acceptable, but who will actively defend that position. The last message, perhaps unique to the Navy, is that white supremacy is excusable if there is some form of offsetting behavior: specifically, funneling huge piles of taxpayer cash to the fleet.

Figure 3: ‘Peace in Union.’ The surrender of Lee to Grant at Appomattox Court House, Virginia, Apr. 9, 1865.  Source: Painting by Thomas Nast, 1895 (Granger Historical Picture Archive).

Source: Painting by Thomas Nast, 1895 (Granger Historical Picture Archive).

This isn’t a question of heritage. If some of today’s Americans are proud of their Confederate soldier ancestors, let them be proud. This is a question of leadership, and message — a deeply wrong message that only compounds the long and well-documented resistance to equality for citizens of color. The message that’s sent to American soldiers today is that white supremacy is something that the Army and Navy are proud of. That it’s part of our history. While it is part of our history, it is just not a part that we should be proud of. The Department of Defense needs to make it clear that it is not erasing history, but that these people did not stand for the things we stand for today. Who they were is not who we are. It is past time to remove the vestiges of white supremacy by removing the names of white supremacists from the U.S. military’s bases, ships, streets, buildings, facilities, and schools. The U.S. military must tackle the deeply unjust remnants of institutional racism by first cleaning its own house and ensuring that vestiges of white supremacy are not baked in.

Col. Mike “Starbaby” Pietrucha is an experienced fighter/attack aviator with over 1700 flight hours and 1506 combat missions in the F-15E and F-4G. He is in the throes of retirement from the U.S. Air Force after almost 32 years of commissioned service.

The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Department of the Air Force or the U.S. government.

Image: U.S. Army

CORRECTION: A previous version of this article incorrectly identified two U.S. legislators. John C. Stennis was a senator from Mississippi, not Missouri. Carl Vinson was a member of the House of Representatives, not a senator.