Pandemics and the U.S. Military: Lessons from 1918

“We are not at war. Sailors do not need to die. If we do not act now, we are failing to properly take care of our most trusted asset — our Sailors.”

– Capt. Brett Crozier, USS Theodore Roosevelt, March 30, 2020

The novel coronavirus will hit the U.S. military and its allies hard, as already there have been outbreaks at the Marine Corps boot camp at Parris Island and on the aircraft carrier USS Theodore Roosevelt. How hard will depend on a number of variables — some having to do with the virus itself (how and to what extent it mutates, whether it comes back in subsequent waves, etc.) and others having to do with what measures militaries take to protect themselves. But it would be foolhardy to underestimate the damage COVID-19 could do.

Fortunately, we have a historical example that could offer some clues on how the virus might affect the military, the kinds of policies that might exacerbate or mitigate the pandemic’s impact, and the policy choices that at some point today’s military leaders may face. I am speaking, of course, of the 1918 influenza epidemic — commonly referred to as the Spanish flu, although experts agree it had nothing to do with Spain. They are not, in fact, sure where it came from, though the outbreak in the United States clearly began in March 1918 in Kansas, and from there it spread Europe thanks in large measure to the flow of U.S. troops to France.

The 1918 pandemic placed America’s military leadership in the position of having to make difficult choices. The disease was killing soldiers, sailors, and marines, undermining readiness and the Army’s ability to fight. Measures to protect the force and the many civilians it came in contact with, however, likewise hindered readiness and, most importantly, threatened to throttle mobilization. 1918, it must be remembered, was the year of Germany’s great spring offensive, which aimed to defeat the exsanguinated allies before the United States was able to make its full weight felt on the battlefield. From March to July, the outcome of the war hung in the balance, and what the allies needed more than anything to prevail was American manpower as quickly as possible. They made the choice to prioritize mobilization, accepting the human toll as a grim necessity.

Fortunately, military leaders today face a more benign security environment than their predecessors a century ago. The U.S. military is engaged in military operations abroad, but it is not fighting a great-power war. As a result, the Pentagon has every reason to do everything in its power to stem the current pandemic — even if it has to absorb some downgrade in readiness.

Pandemic and the American Military in World War I

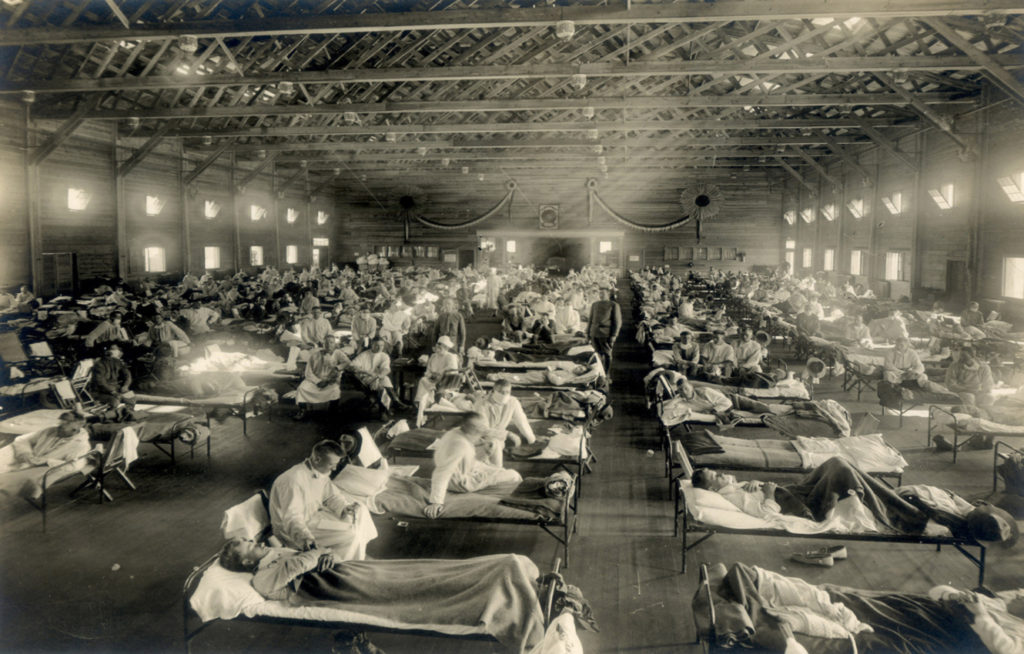

The toll of the pandemic on the U.S. military is well documented. In 1918, 121,225 marines and sailors were hospitalized with influenza, and at least 4,000 died. Several ships had to return home to port or were effectively crippled. The Army was far more heavily hit as the flu ravaged its large training camps that had been set up across the country and in France after the United States entered the war.

The pandemic started at Camp Funston, Kansas, in March 1918 and then quickly spread from there. U.S. Army camps were major hotspots. An average of 25 percent of the soldiers there were sick during the autumn wave of the pandemic, although in many camps the rates were at 50 percent or above. The pandemic swept through the camps—as id did the rest of the world–in three distinct waves. The first was in the spring, the second in the fall in during September and October, and the third in the winter of 1918–1919. In all, 791,907 American soldiers were hospitalized in the United States or France, and 24,664 of them died. One in 67 soldiers died of the flu or the associated pneumonia in 1918. The American Army also spread the disease to the French, who had their first reported cases in April. By mid-May, anywhere from 10 percent to 70 percent of the soldiers in French units were sick — and this was in the midst of the great German spring offensive that began March 21 and lasted until mid-July. France lost a total of 53,000 soldiers to the flu — 130 out of 1,000 French soldiers got sick (436,000), and it killed 10 out of 1,000, or six divisions. The British, Germans, and nearly everyone else got the disease as well, although the waves of the pandemic hit the British and Germans a little after they hit the Americans and French.

The pandemic interrupted training, aggravated manpower shortages, and hampered operations in myriad ways. Sick soldiers could not report for training or for duty, while weakened soldiers performed badly. Low unit morale likewise undermined effectiveness. Commanders who called for units to replace those lost to attrition found there were fewer replacements than what they had asked for. Moreover, weakened and undertrained soldiers would have done poorly in combat, suggesting that more soldiers were wounded or killed than might otherwise have been the case. Once hospitalized, many sick or wounded perished because the combined influx of flu cases and battle casualties overwhelmed the medical system. No one knows how much better American, British, and French units might have performed fending off the German spring offensive if they had been healthy. Likewise, it’s unknown how much better the American Expeditionary Forces might have performed during the Meuse-Argonne offensive, which coincided with the pandemic’s lethal second wave and was one of the bloodiest campaigns ever fought by the U.S. military.

For America and its allies, perhaps one saving grace was that the German Army was also sick. German Gen. Eric Ludendorff in his memoirs named the flu as one reason for the final failure of Germany’s spring offensive. Historian Elizabeth Greenhalgh confirms that the flu hampered preparation for the “Gneisenau” offensive launched on June 9 — and we know that the disease seriously weakened a number of German units in the critical months of June and July. On the other hand, Greenhalgh also notes that Ludendorff in September, on the verge of a nervous breakdown, resisted a proposal to make a major strategic retreat in part because he “clutched, like a drowning man at a straw,” the news that there was an outbreak of “pulmonary plague” in France.

The American and other militaries’ medical services did a good job of reporting the outbreak of the flu as it happened. However, there was a delay in identifying the problem as both distinct and more dangerous from the normal seasonal flu and any of a host of maladies. The first wave, moreover, was relatively mild and those more easily confused with the seasonal flu; the second wave was more lethal. Though Army medical officers did not know the exact cause of the flu and had little means of treating the sick, they did have a good set of tools for combating the spread of the contagion, best practices that we recognize today: rigorous sanitation, isolation, quarantine, social distancing, and attempts to relieve overcrowding. They found that soldiers and units who were isolated for purpose or some other reason tended to fare better. For example, black troops were generally sick less often than white soldiers because they were physically segregated. (Though Black soldiers were often more likely to contract pneumonia.) In some camps, they were even housed in tents while white soldiers were housed in barracks, and soldiers in tents with limited occupation did better than those housed in large barracks. In general, the less crowded the living conditions, the better.

Ending mass assemblies or any gatherings also helped. In some hospitals, the staff draped tent cloth around hospital beds to isolate patients and alternated their orientation with respect to where the foot of the bed was versus the head of it. There is no indication of whether the tenting or the bed alternating helped. In any case, until September of 1918, there were few Army-wide instructions for dealing with the flu, leaving it up to individual medical officers and base commanders to act as they saw fit. Meanwhile, there were practices that fueled the pandemic: Conscription kept new recruits flowing into the training camps (although in the fall the Army suspended the draft to alleviate the problem) and soldiers kept moving from base to base. In France, American military hospitals, along with British, French, and German hospitals, were often simply too overwhelmed by the burden of having to care at the same time for flu patients and those with battle injuries, and they lacked the resources to deal appropriately with the pandemic.

As Carol Byerly recounts, the issue of troopships became particularly contentious. Troopships were undeniably dangerous, with large numbers of soldiers contracting the flu on board. Some died on the way to France; many arrived in France only to compound the health crisis there. The Army’s acting Surgeon General Brig. Gen. Charles Richard in the fall of 1918 — at the time of the second wave — urged Chief of Staff Gen. Peyton March to quarantine troops for a week before they boarded ships and to reduce the capacity of the ships so as to make them less overcrowded. March refused, insisting that the practice of screening troops before they boarded was sufficient, regardless of the fact that many soldiers who had the flu may well have been asymptomatic when screened. Richard then insisted that the transports to France be suspended. March told President Woodrow Wilson that slowing down the growth of the American Army in France would only encourage Germany, which at the time was retreating. The risk was worth it, according to March, because a soldier who died of influenza, he told Wilson, “has just as surely played his part as his comrade who has died in France.” Wilson agreed.

Lessons for the U.S. Military Today

As America’s military leaders weigh options to keep servicemen and women healthy and safe from COVID-19, they have a number of advantages over their predecessors, including advances in medical technology, the sharing of information, and the fact that the United States is not currently involved in a major war. Yes, the United States is conducting numerous military operations abroad, but they are less dire than the Western Front in 1918. Moreover, modern warfare is relatively more compatible with strong public health measures than was the case back in the day.

It stands to reason that military commanders — with some creativity and flexibility — should be able to protect the force during COVID-19 while minimizing negative effects on readiness. Downstream effects related to interrupted training, for example, may be inevitable. On the other hand, the price to be paid for not doing everything possible to impede the spread of the pandemic in terms of readiness and letting soldiers (along with their families and any other civilians with whom they interact) get sick could be significant. The Marines recently closed Parris Island to new recruits to protect them from getting sick, though not before there already was an outbreak of COVID-19 among the recruits already there. One has to wonder what took them so long. The captain of the USS Theodore Roosevelt is asking for help quarantining his ship’s crew. Marsh and Wilson believed they had to throw every available man, sick or not, into battle in 1918. Fortunately for us, Ludendorff is long gone. Now, the U.S. military can and should focus on the pandemic.

Michael Shurkin is a senior political scientist at the non-profit, non-partisan RAND Corporation.

Image: National Guard Bureau