A New Era of Military Comedy from the Ranks

Netflix original series “Space Force” is set to air May 29. It’s a workplace comedy starring Steve Carell about the emerging sixth service of the American military. As a parody of the military, it’s a rare find. Consider the last time you watched a comedy about the American military that actually hit home. It probably wasn’t produced in the last couple of decades. American society today is almost always reverent toward its military. There is one demographic, though, that still jokes about military experiences: servicemembers themselves. Those who have worn the uniform have begun to create their own military comedy, and it contrasts sharply with society’s current image of the institution.

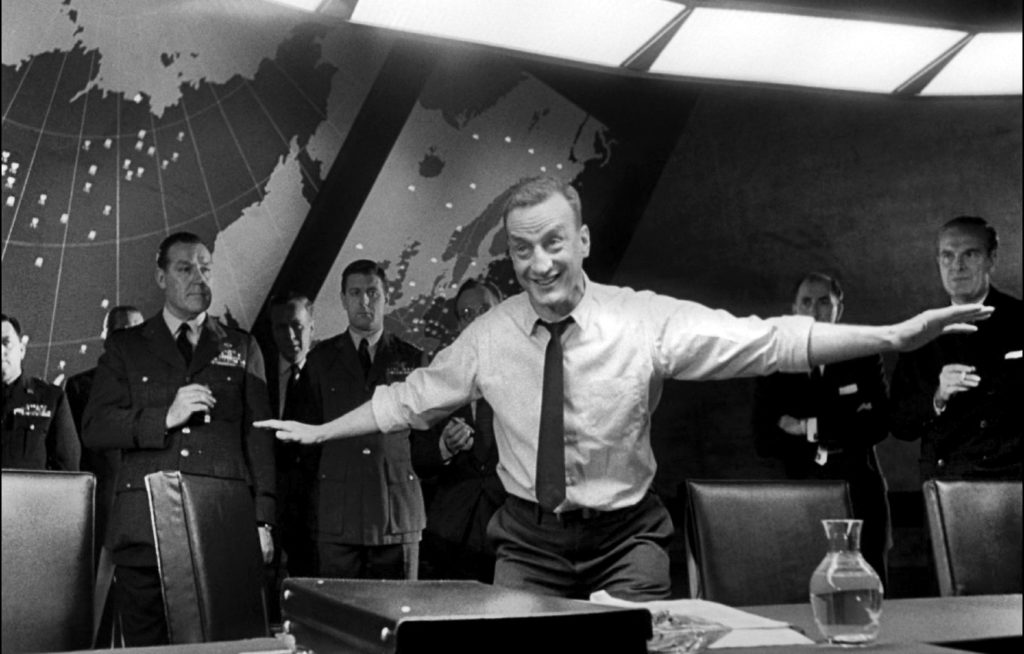

There’s a rich history of comedy about military life in American culture. The Phil Silvers Show, which ran on CBS from 1955 to 1959, features Sgt. Bilko, a lovable crook and conniver in uniform. McHale’s Navy, which ran on ABC from 1962 to 1966, is a spoof on buffoonery in leadership and sailor shenanigans set in the Pacific during World War II. Hogan’s Heroes, which ran on CBS from 1965 to 1971, parodies U.S. airmen as prisoners of war in Germany. Each of these shows portrays military leaders as inept and unprincipled — in other words, un-military. From books like Catch-22 to movies like Dr. Strangelove to television shows like “M.A.S.H,” comedies were often used to satirize the absurdities within the military bureaucracy. Comic strips like Grant’s Grunts illustrate the soldier’s experience at war and mock various aspects of military life, like filling sandbags as part of the fight against the Viet Cong. And there are dozens more examples like Operation Petticoat (1959), Private Benjamin (1980), and Stripes (1981).

At the time that these comedies were made, military experience was widespread, and the American audience was full of veterans. As James Fallows explains in his seminal essay “The Tragedy of the American Military,” such comedies suggest a “culture close enough to its military to put up with, and enjoy, jokes about it.” An audience with military experience recalls and identifies with themes like the foolishness of leaders and incredible absurdities in the military and in war.

Flash forward to today. Less than 1 percent of Americans serve, and the burden of military service is borne by the same families and communities. The military is, as Fallows writes, “exotic” to most Americans. And at the same time, such productions and themes like those of the “M.A.S.H.” era are practically unthinkable. Today almost all depictions of the military in popular culture are reverent and sobering. Military personnel are glorified as warrior heroes, from films like Lone Survivor, Restrepo, and Zero Dark Thirty to shows like “SEAL Team.” Even cultural features like Vogue’s “Women in the Military” or the National Portrait Gallery’s recent “The Face of Battle” exhibit, which examine the human dimension of war, are almost wholly serious. Sometimes contemporary war stories are so grandiose that they feel like recruitment ads, glamorizing service. And when soldiers aren’t displayed as valorous warrior heroes, they’re tragic heroes, battling post-traumatic stress disorder in American Sniper or Thank You for Your Service, as Sebastian Bae notes. Regardless, they are distant characters from the citizens they serve.

Children’s letters to deployed soldiers offer a glimpse into the extent of the gap between soldiers’ recent experiences at war and the public’s imagination of them. This rather irreverent Imgur album shows some of these letters, which include notes like, “[you’ll] probably never get to see your family again” and “My dad says you guys are fighting a bunch of goat fuckers.” It’s no surprise that a child misunderstands something as complicated as war, but it is surprising that their parents and teachers seem to.

To be sure, there have been a few underwhelming attempts at military humor in recent years. SNL tried and failed to make fun of veteran and now-U.S. Rep. Dan Crenshaw a couple of years ago; The Men Who Stare at Goats (2009) received weak reviews overall. Some appreciated War Machine (2017) for its hard-hitting criticism of the war in Afghanistan and the hubris of some top brass, but many disliked the film overall, especially for its misrepresentation of Stan McChrystal as an idiot. The Hulu miniseries “Catch 22” is no “M.A.S.H.” That these were largely flops points again to the gap between civil society and military life; the humor apparently isn’t on point for soldier/veteran audiences, and civilian audiences just aren’t receptive to it.

The decline of military comedies in popular culture doesn’t mean that there’s nothing to laugh about anymore. The military still resembles the military of past generations — an imperfect bureaucracy full of fallible personnel. But now, only a small percentage of the population is intimately familiar with these many defects. Few understand the military enough to joke about it. So now, faced with only exaggerated or gloomy stories from the outside, many servicemembers create their own comedic content. There’s a whole world of homegrown military humor, especially online. In 2010, then-Marine Maximilian Uriarte launched “Terminal Lance,” a comic about life in the Marine Corps that quickly exploded in popularity. A couple of years later, Army veteran David Abram’s Fobbit (2012) was published, which satirizes life on a forward operating base in Iraq. And Marine veteran Paul Szoldra started Duffel Blog, an online publication featuring satirical reporting on national security and military topics, written mostly by contributors with military experience. Its enormous popularity has led to a book, merchandise, and praise from James Mattis.

There are also Facebook pages like “Decelerate Your Life,” a play on the Navy’s former slogan “accelerate your life,” and “U.S. Army WTF! moments.” Its Facebook page boasts nearly 1.3 million followers and is notorious for amplifying military hijinks, slipups, entertainment, and news. Many soldiers (and commanders) follow its content religiously. There is an abundance of Instagram pages like “spaceforceactual” and “sad_officer_memes.” And the Twitterverse is teeming with accounts created by servicemembers that frequently mock aspects of military life. Twitter’s @pptsapper has a loyal readership, and @LadyLovesTaft is so influential that she spoke about leadership in the digital age at last year’s Association of the United States Army Conference.

These outlets vary considerably in medium and content. Duffel Blog is an established publication that vets its contributors and articles, but many of the social media pages are chaotic. They often feature crude, lowbrow humor. Owners of “mil-twitter” accounts tend to share as much personal information as they do military-related content. But these outlets are alike in that they illustrate daily life through the lenses of servicemembers. They joke about military life. And to be sure, many professions and organizations have their own comedic subcultures and quirks, especially as “meme culture” has exploded in the past couple of years. But the military’s subculture is curious because of how it contradicts popular culture’s portrayals of military life.

Servicemembers create comedy for a variety of reasons. For one, it’s humanizing in a time when the public’s image of servicemembers isn’t. The public’s excessive admiration of soldiers, however well-intentioned, is alienating. Heroes are characters, not real people. As Twitter personality @LadyLovesTaft, 1st Lt. Kelsey Cochran, said last fall, “A lot of what I do online is trying to humanize servicemembers.” Secondly, humor can help to relieve the stress induced by deployments and the military. Stand-up comedy, for example, helps some veterans to process their experiences. And all humor — even something as simple as a witty tweet — allows people in military communities to lampoon themselves, taking themselves less seriously than the rest of the country does. Finally, soldiers, who are taught values of teamwork and selfless service, have a general discomfort with the concept of personal glory, a theme central to military dramas. Indeed, there is a sense among servicemembers that the public misunderstands their work, gilding it with false shine. Of course, the reality of a profession is typically more banal than representations of it, but it doesn’t feel like the public understands that difference when it comes to soldiers’ work. Instagram pages that rebrand the Navy slogan “accelerate your life” to “decelerate your life” poke fun at this discrepancy.

Respect for military service is warranted. Even if a soldier never deploys, to work for the military requires the burden of relocation every three years or so, many late nights and early mornings, and frequent family separation for various training. But there is a fine line between respect and worship. On my deployment, I received an overwhelming amount of care packages and notes from schoolchildren. While I am deeply grateful for this generosity, it also made me feel guilty and misunderstood. (If only the senders could see how much coconut water I mailed to myself via Amazon…) I didn’t need care packages, but I did want to laugh with people who understood my situation. For this reason, I appreciated Duffel Blog’s Afghanistan commentary more than anything.

Caroline Bechtel is an Army officer stationed at Fort Bragg, North Carolina. The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect those of the U.S. Army or any part of the U.S. government.

Image: Wikicommons