Poor Leadership During Times of Disease: Malta and the Plague of 1813

Disease ravaged the population. Thousands died and those who survived were forced to isolate themselves in their homes as medical officials attempted to purge the pestilence from the area. The economy, previously growing and sound, came to a standstill. Blame for the disaster was widespread, but it was an absence of leadership that bore the brunt of responsibility. The government officials charged with protecting the population were lax in preparation for a possible disaster and were often insufficient in their response to events.

While the above description could apply to any number of countries suffering from the current COVID-19 viral outbreak, the opening paragraph describes another historical example when pandemic brought a country to the brink — the outbreak of plague on the islands of Malta in 1813. By far the most covered historical incident has been the Spanish flu pandemic of 1918, though it is by no means the only other example. Reconstructed from official correspondence, private letters, and investigatory commissions, Malta’s experience with the plague provides a good example of how poor leadership decisions can exacerbate an already bad situation and the consequences for an unprepared population.

Malta and the British Empire in 1813

Malta is a small archipelago located 60 nautical miles south of Sicily. In 1813, roughly 91,000 Maltese people lived on the largest two islands. The people were governed by the British Empire, who in 1800 helped liberate the islands from the French (who had themselves seized Malta from the Knights of St. John in 1798). As often happens with liberators, the British decided to stay after the fact, and they took over administrative control of the island chain.

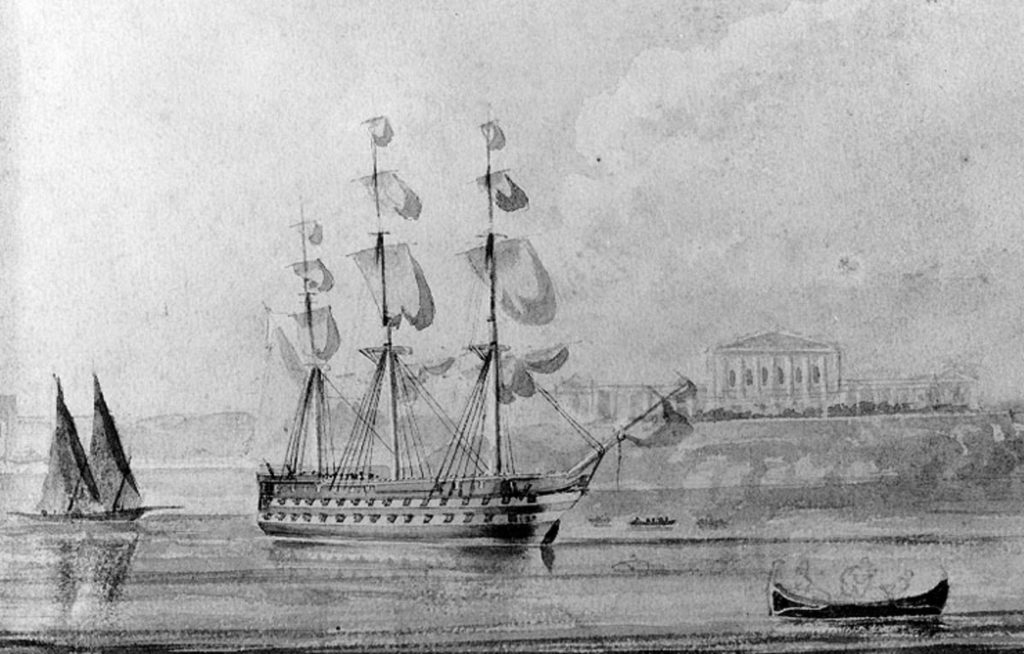

One of the reasons the British stayed was the economic potential of Malta. The country was small, but its geographic location meant it was a crossroads in the Mediterranean. Grain from Sicily, cattle from Tunis, cloth from Egypt, fruit from Greece, and a wide variety of other goods were stored next to each other in Maltese warehouses, with the sailors who transported said goods carousing in the dockside taverns. One commonality? They were all vectors for disease. This was an old, familiar problem for the Mediterranean; the region’s active shipping trade helped spread contagion. Even in the early 19th century, outbreaks of the plague were common.

The Mediterranean also employed an old, familiar solution to defend against disease: quarantine. A port needed the proper implementation of quarantine rules, and the administration of a lazaretto — a series of buildings designed to house possibly infected goods, people, and ships until deemed safe. Malta was fortunate enough to have a good record when it came to its quarantine practices. Its capital, Valletta, had facilities that for decades held an institutional reputation for quality and safety within the Mediterranean. This helped allow trade to continue despite years of war and economic hardship.

To continue that reputation, the British administration created a position: the superintendent of the quarantine. The first person appointed to the job, and subsequently the first to fail in leadership, was William Eton. It was not that Eton was incompetent at his job — by most accounts he was a capable quarantine administrator. The problem was he spent as much time conspiring against his superior, and trying to take his job, as he did executing his official duties. When he failed to get a promotion, Eton left the islands in 1802, claiming ill health, but promised to return.

Eton never returned to Malta. This in and of itself is not noteworthy but for one crucial factor: he never lost his job. Inexplicably, Eton retained his position as an absentee superintendent of the quarantine, despite attempts by Malta’s civil administration to have him removed. It was not until nine years following his departure when Eton was finally replaced by William Pym in late 1811. Unfortunately, Pym only spent a few months on Malta before asking for a leave of absence due to poor health. As a result, for more than a decade the most important position when it came to the health of Malta remained vacant. This was a critical gap in leadership and a major failure by those responsible for assigning the position.

To compensate, Malta’s civil commissioner, Lt. Gen. Hildebrand Oakes, created an ad hoc board of health to help run the medical facilities. The board consisted of a mixture of Maltese officials and British army medical personnel. It was a well-meaning group, but it could not fully dedicate the time and attention required by the Quarantine Office. These individuals had their own jobs and other responsibilities, making the Board of Health of secondary importance to them. Thus, a decade of little to no leadership meant that Valletta’s lazaretto suffered from poor supervision and lax rules — a potentially disastrous combination given the department’s responsibilities. This was proved in April 1813 when the plague began running rampant through the islands.

The Plague Begins

The exact origins of the epidemic remain unknown, but there were two likely vectors, both ultimately falling under responsibility of the quarantine department. In March of 1813, Alexandria, Egypt, was suffering from an outbreak of plague. A ship from Alexandria docked in Valletta, and two sailors died from suspected plague while in quarantine. There is also a good possibility that illicit goods, also originating from Alexandria, were smuggled into Valletta without going through the proper quarantine protocol. Either way, the lax atmosphere at Valletta’s lazaretto led to the spread of disease beyond the secure warehouses and buildings.

The weeks following the arrival of the plague-ridden ship from Alexandria were relatively calm. It was not until mid-April that a death was directly attributed to the plague. It was an eight-year-old girl, the daughter of a shoemaker who lived on one of the main thoroughfares in Valletta. The next day her mother died. The father also fell ill, and soon the entire surviving Borg household was placed in quarantine at the lazaretto, along with those who had close contact with the sick family. Those measures, while prudent, were not enough to stop the plague from spreading through the city. Between May 12 and 22, 30 people died of the plague. By the end of the month, just eight days later, 109 people in total had perished. Pestilence was ravaging Valletta, and the British government could do nothing.

Commissioner Oakes and the Board of Health tried to stem the tide. Placing the Borg family in quarantine once their symptoms were discovered was a smart move, and the Board of Health posted public flyers in both English and Italian giving advice on how to best protect people’s health. Yet while Oakes was complimentary of the board’s efforts, they did not always see eye to eye on Malta’s best course of action to combat the plague. For instance, when the ship from Alexandria docked at the lazaretto, members of the Board of Health wanted to immediately destroy the ship and its cargo while the sailors waited the requisite number of days in quarantine. Oakes, interpreting Malta’s quarantine rules differently, insisted that the owners of the vessel must be allowed to remove their property and then return the vessel to Alexandria. Ultimately, the Board of Health lost the argument.

It was while these types of large policy decisions were being made that Malta’s chronic lack of a full-time superintendent of the quarantine became a serious liability. A superintendent’s experience and bureaucratic weight would have been a valuable resource for Malta. As it was, the Board of Health and civil commissioner continued to butt heads, fighting over how important it was to keep people isolated in their homes. Within months there was not a town on the entire archipelago that was not touched by plague.

As with any crisis, there was no shortage of people trying to peddle a solution. Even in London, British authorities received several unsolicited letters from gentlemen who believed they knew the solution to Malta’s problem. One man callously suggested forcing all British residents in Malta onto the small and sparse island of Comino and letting the Maltese fend for themselves until the plague died out. A chemist from Leith wanted to pump hydrogen into all the houses to push out the bad humors. Yet another man promised to find the solution or die trying, so long as he was paid three guineas a day.

Ultimately, what stopped the plague in Malta was the adoption of measures similar to, and in some cases more extreme than, what modern governments are trying for COVID-19. People were not allowed to move between towns or districts in a city without explicit written permission, some towns were isolated by military force, and offenses like hiding your own illness or concealing others’ illness became punishable by death. When the disease finally disappeared from Malta a year later, the death toll was around 4,500, approximately five percent of the total population.

In addition to the loss of life, Malta experienced economic losses in both short-term and long-term commerce. The short-term effects were severe. Because of the restrictions on movement, all nonessential interisland commerce was completely suspended. Public areas were shut down, churches and businesses shuttered. International shipping, with the exception of emergency supplies, was nonexistent. Though they understood the danger, merchants still complained about the restrictions. Food became more difficult to acquire, especially by people who found themselves surrounded by a military cordon. The responsibility fell on charitable organizations and the civil government to ensure people were sheltered and fed. Money infusions from London were required to keep the government afloat.

Due to the plague, Malta’s reputation was now tarnished. Merchants from other ports, particularly those controlled by Italy, took advantage of the weakness. They used Malta’s poor standing as an excuse to increase the wait time in their quarantines for ships hailing from the island. This caused a cascading reaction, and shipping went elsewhere to avoid delays.

Some of the damage was self-inflicted. The fear of a reoccurrence led to stricter-than-normal quarantine measures even five years after the event. As a number of ships discovered in 1819, sailing into Valletta’s Grand Harbor before visiting the lazaretto and quarantine facilities in the neighboring Marsamxett Harbor meant a hefty fine. Even if it was an accident, it cost a ship’s master £200 for the mistake (roughly equivalent to $15,000 today). Long waits and punitive fines did not help attract merchants to Malta, but fears of another outbreak outweighed the consideration of these consequences.

Finally, Malta’s ordeal came with significant political ramifications. Even before the plague struck Malta, British policymakers had decided to assert a stronger grasp on the islands by formally designating it a Crown Colony. For the Maltese people, this meant that the civil government and military administration, hitherto separate entities, now combined under one executive position: governor. This was something that many Maltese did not want to have happen. From the moment the British occupied the islands, the Maltese made it clear that their preference was to have a civilian authority separate from the military. The British authorities feared widespread revolt when the first governor, Thomas Maitland, arrived on the island. However, the plague sapped the strength of any resistance the Maltese people might have made against the new governor. People who are not allowed to leave their houses and villages cannot protest.

Lessons for Today

There are certainly important differences between the current COVID-19 situation and the ordeal Malta went through two centuries ago. Modern understanding of medicine and how a disease spreads throughout a population is exponentially more advanced. COVID-19 is also a global problem, affecting dozens of nations on multiple continents.

Despite these differences, modern policymakers can learn from Malta’s experience two centuries ago. First and foremost, Malta’s experience emphasizes the need for clear leadership. Without it, delay and confusion are inevitable. It also shows the importance of heeding technical and scientific expertise — COVID-19 will not be the last pandemic crisis. Second, it is important to remember the political ramifications of disease, be it the plague in 1813 or COVID-19 in 2020. In Malta, a potentially controversial executive authority took power while the people stayed isolated for fear of sickness. In the United States, policymakers should take measures sooner rather than later to mitigate any disruption to the elections this fall. Finally, separation, isolation, and social distancing worked in Malta to reduce the spread and impact of the disease, and it can work for the current crisis. The economic cost of these measures in 1813 was high, but weighed against saving lives, it was a price worth paying.

Andrew Zwilling is an assistant professor of strategy and policy at the United States Naval War College. He is currently cowriting a book on the war for American independence and is in the process of converting his dissertation on early British rule in Malta to manuscript form. The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not represent the views or policies of the U.S. government.

Image: U.S. Navy