Germany, Wilsonianism, and the Return of Realpolitik

“The idea of the ‘great power competition’ is not only influencing the strategy papers of today – it is also shaping a new reality all across the world”

– Frank-Walter Steinmeier, German President, Munich Security Conference, Feb. 14, 2020

In the sentence above, notice the quotation marks around “great power competition.” The quotes illustrate how strange it must have felt for Frank-Walter Steinmeier, the German president, to speak of such dirty business as power politics. The entire sentence illustrates how new and alien this concept still sounds to most Germans. Whether they want to or not, Germans will have to get used to this type of rhetoric.

Until now, President Woodrow Wilson was the American statesman and moralist who implicitly shaped German foreign policy thinking. Wilson fathered the League of Nations and supported the notion that an international order should replace the chaotic and belligerent reality of international relations. In other words, Wilson advanced the idea that nations should talk their issues out instead of being so barbaric as to resort to violence. Global peace and human rights should replace power and national interests as the ultimate goals of states’ behavior. Until today, Germans have remained deeply committed to these ideas.

As the United States pivots toward Asia and weakens old alliances that it created and guided in Europe, Germany is becoming more independent. No longer under America’s shadow, Germany becomes exposed to the anarchy of international relations. Berlin’s foreign policy will necessarily become more realist as Europe’s biggest country increasingly has to fend for its own interests.

Wilsonianism and Germany Foreign Policy

Wilsonianism crossed the Atlantic in various forms: Through the G.I.s in the aftermath of World War II, who had grown up with the concept of American exceptionalism combined with Wilsonian morals; through movies and pop culture; and through the occupation officials who had served under Wilson and shared his ideals. Germany was not only de-nazified, de-militarized, and democratized — it was also Wilsonified. According to a 2016 PEW study, 62 percent of Germans believe that human rights should be the main goal of foreign policy and 64 percent responded that military action was not the way to combat terrorism. Wilson would be proud.

German Wilsonianism is often mistaken for pacifism. They are, however, distinct. Pacifism is the strict rejection of any use of force, irrespective of the goal. Margot Käßmann, leading German pacifist and former head bishop of the Protestant church in Germany, famously said in 2014 that even the war against Nazi-Germany was unjust — only peace was just.

Wilsonianism, on the other hand, accepts a narrow set of reasons for military intervention. The protection or enforcement of human rights sits chief among them. Both pacifism and Wilsonianism, however, adhere to strictly ethical goals. Neither would accept the realpolitik goals of stability and order as valid and especially not using military means to achieve them.

Subsequently, the debate in Germany has not been between pacifists and realists, but between pacifists and Wilsonians. Foreign policymaking has been a contest of moral merit. National security debates were more about who could argue for the higher cause in terms of the absolute good. The winning argument to join the intervention in Kosovo — which faced fierce pacifist resistance — was not focused on national security concerns, but instead on “never again Auschwitz,” the ultimate moralistic superweapon. Joschka Fischer, then Vice-Chancellor and Foreign Minister, made the case for intervention to Germans in 1999 by arguing that genocide was happening in Kosovo and its prevention was a pivotal historic and ethical goal, more so than the goal of never engaging in another war. Not everyone was convinced, however, and one pacifist even threw a balloon filled with blood-red paint at him, rupturing Fischer’s eardrum.

Until quite recently, Germany could afford the cost of such exercises in moral purity. The country has enjoyed an unprecedented period of prosperity and security since 1949. Without any external threat, the country kept its culture of restraint, even after reunification when many outsiders had worried about a reawakening of German ambitions. The country’s strategic outlook had become exclusively focused on its immediate borders during the Cold War. In the 1990s it finally seemed to be exclusively surrounded by friends. Even Russia appeared to be on the road to capitalism and democracy, and Germans rejoiced in the end of history.

The End of the End of History

Then came President Donald Trump. By the time he arrived on the scene, Germany had gotten somewhat accustomed to using its military — in Kosovo, Afghanistan, and a few other theaters — even if it did so anxiously. Moreover, Russia had given German Wilsonians a practical reminder in 2014 that not everyone in the world was running on utopianism. Then came the most difficult lesson: German Wilsonians learned the hard way that their nice idea of a global order and legal system rested entirely on truly powerful nations: the United States and, increasingly, China. Their commitment to this order, and their will to enforce it, are necessary requirements for its functioning. In the end, the world still runs on power.

These lessons are now setting in. While Steinmeier had the usual Wilsonianisms in this year’s speech at Munich about building a “supranational legal order” and establishing “world peace,” he also said he was “advocating realism” and that Europe was Germany’s chance of pursuing its interest. He even said that “we will not succeed … from a position of weakness.” One swallow does not make summer, but there are more and more birds chirping a similar tune by now.

While there is an argument to make that Germany started to become more realist earlier, the 2014 Russian annexation of the Crimean peninsula and, most notably, Trump’s election, paved the way for a shift away from Wilsonianism. In 2014, the German president, foreign minister, and defense minister separately announced that it was time for Germany to take on the responsibilities befitting a country of its size and economic power. Three years later, Angela Merkel said that Germany could not, “to a certain extent,” rely on the United States any longer. In 2018, the current Foreign Minister Heiko Maas said, regarding the United States-led system, that “this world order no longer exists.” More recently in December of 2019, after the U.S. Congress had announced sanctions on companies involved in a German-Russian gas pipeline project (provocatively dubbed the Protecting Europe’s Energy Security Act), Germany responded angrily that “decisions on European energy policy are taken in Europe” and that the country “reject[s] foreign interference.” After the United States withdrew from the Iran nuclear deal, Germany announced a European financial transaction system that would be able to circumvent American unilateral sanctions in the future. German Minister of Defense Annegret Kramp-Karrenbauer advocated for a European aircraft carrier in order to project European power. In October of 2019, Kramp-Karrenbauer went so far as to actively propose the establishment of a “security-zone” in Northern Syria with German and allied troops, which would have given Germany some leverage in the region. Several leading German politicians have come out in favor of strengthening European military power to balance against waning American influence and increasing disinterest. In a recent interview with the Financial Times, Chancellor Merkel put an even stronger emphasis on German national interest as a driver of Germany’s ambitions.

Such realist sentiments are increasingly reflected in public opinion polls. According to a recent study from the German Körber Foundation and PEW, only 22 percent of respondents believe that Germany can still rely on the United States’ nuclear umbrella and 31 percent would prefer that Germany be neutral rather than a member of the United States-led West. More Germans want American troops to leave their country than to stay, and almost three quarters would rather be independent of the United States in foreign policy.

Despite the increasingly realist rhetoric and public sentiment, German foreign policy remains void of any greater ambition or vision. When French President Emmanuel Macron called NATO “brain dead” and pushed once more for his vision of a militarily stronger and more relevant Europe, reactions in Germany were cautious at best. As Barbara Kunz rightly noted, NATO is dominated by the United States. Germany — in contrast to the French — has been careful, if not afraid, to emancipate themselves from traditional ways of thinking. The United States, however, is increasingly weary of its European allies that have little to contribute to its competition with China. It is quite likely that the United States will dramatically decrease its involvement in NATO at some point and focus more on Asia. America may even withdraw from NATO if Trump is reelected. Germany, however, is so used to thinking and working within the confines of the transatlantic alliance that it has no Plan B, and rejects Macron’s pleas for considering one.

Speeches like President Steinmeier’s still ooze with hopes for a Wilsonian world. Those hopes are misplaced. The Wilsonian idea is built on the illusion that there could be a higher force bringing order to the anarchy of international relations. In practice, the system is anarchic — there are just states. There is no world police that is independent from nations and governments. Instead, “the strong do what they can, and the weak suffer what they must,” as Steinmeier correctly quoted Thucydides. The past 75 years have been the only time in the millennia of human history when a global supranational order in the form of the United Nations existed. When looking closely, however, it was merely a construct to amplify the power of the powerful. The most powerful countries agreed to grant themselves a veto power in the security council, that sits atop the rest of the member states. These so called Permanent 5 (Britain, China, France, Soviet Union/Russia, and the United States) still control most of the relevant committees and other powerful international organizations. Moreover, when domestic interests were at odds with the United Nations, the most powerful countries ignored or broke the rules. The Wilsonian belief in international law and order has been proven again and again to be unrealistic. While the United Nations definitely provides a platform for diplomatic exchange and has helped numerous people through its caritative organizations, it is at the grace of the great powers. International law is not a necessary outcome of international relations. It rests on the commitment of the powerful to respect and enforce the rules even when they would hurt themselves. This commitment never existed.

Germany remains reluctant to pursue a more realist foreign policy because there are two hearts beating in the German chest. On the one side, Germans finally begin to acknowledge this anarchic reality of international relations. The Iraq War, Putin, and Trump have deprived them of the illusion that the country could ignore geopolitics. Moreover, as the United States shifts its focus to Asia, its alignment with Germany and German interests diminishes. Germany will be forced to learn how to assert itself without the constant support and influence of the world’s biggest power. The debate on defining German national interests — and even whether Germany should even have national interests — has been moving in that direction for almost two decades now. On the other side, 75 years of partnership with the United States — and its tremendous influence — do not vanish overnight. Scores of soldiers, politicians, bureaucrats, journalists, and academics have been trained to think and act as transatlanticists and hesitate to change their beliefs. Seeing this disconnect between the increasingly realist rhetoric and the slow-changing reality, some rush to the conclusion that German foreign policymaking will never emancipate itself from Wilsonianism — but they are wrong.

The Next Step in German Foreign Policy

In the coming years, Germany will embrace realpolitik in practice, not just in rhetoric. With a fading American commitment and increased interest in Europe, Germany will have to invest more in its defensive capabilities, perhaps embedded in a European institution. While some are skeptical that Germany can implement a more robust defense policy, the country will soon have no choice. Simultaneously, the country will become more assertive and consciously increase its power — probably arguing that it will be for the sake of Europe. Such a move would be a long overdue and necessary consequence of the end of the Cold War, and the new world order defined by Sino-American competition. German pacifism and Wilsonianism could thrive while German foreign policymaking was shaped by Washington. With America’s attention elsewhere, Berlin has become less relevant for the United States. Consequently, current American interests coincide less, and clash more, with German interests.

The time is over when Germans could simply agree or disagree with whatever came out of Washington and then be done with their foreign policymaking. Nothing can change the two governing forces of American strategy — the United States wants to remain the most powerful state in the world, and its primary challenge is China. So long as this is true, Asia will remain the priority theater for U.S. foreign policy, not Europe. This leaves a void — a void that Germans have to fill with own concepts and visions if they do not wish to be steamrolled by the United States as America acts on new interests lying elsewhere. The increasingly realist rhetoric by German leaders indicates that this idea is settling in.

To preserve German Wilsonianism, the United States would have to radically change direction. American foreign policy has, however, been focusing more on the Indo-Pacific for a while now. Any American president had to take on China. Any president had to try to reduce the United States military exposure in the Middle East and South Asia to free up resources. Any president would also point out the unfair burden-sharing in NATO, and no American president could afford to use up the relatively declining American resources to satisfy German moralism. Trump is merely an accelerant for Germans to finally notice what is happening behind the Wilsonian façade of international relations.

How will German foreign policymaking evolve? Wilsonianism will be complemented by a more realpolitik approach. In Scientific Man versus Power Politics, Hans Morgenthau argued that taking action necessarily destroyed moral purity. A recent example might be the Syrian refugee crisis. After initially following their moral impulses in 2015, Germans were hit hard by how their actions divided Europe and their own country. Quickly they led the European Union into a new alliance with an increasingly authoritarian Turkey to block refugees from crossing the European border. Only recently, when President Recep Tayyip Erdogan attempted to use the refugees to pressure the European Union to pay more, did Germany react significantly more cautiously, throwing moral considerations out of the window. Until recently, Merkel’s CDU even rejected the idea of accepting children from an overcrowded refugee camp on the Greek island of Lesbos.

As Germany is becoming more active in global politics, the country will increasingly have to make difficult decisions that will challenge Wilsonian ideals. As Steinmeier also said in Munich “[i]f you want to make peace in Libya, you have to shake a great many hands, not all of them clean.” The next generation of German politicians is already learning about such realities of foreign policymaking and the limits to idealism. Wilson’s influence might not fully leave Berlin’s foreign policy establishment, but dissenting realist voices will join him as the country starts to enforce its own interests with more clarity and without apology.

Not all idealistic dreams should be thrown overboard, though. Realism without ideals is cynical pessimism. It would be hollow and a mere acknowledgement that humans are faulty and will never change. Peace and human rights are worthy goals, but they have to be pursued in a clear-eyed manner, cognizant of humanity’s pitfalls and limitations. Germany would do well to continue its multilateral path with successful and stabilizing organizations such as NATO or the United Nations because prosperity, stability, and order may depend on it. A stable order is easy to take for granted — the current Corona crisis aptly demonstrates this. At the same time, Germany should and already does realize that the world extends beyond Europe. The toolkit of a nation such as Germany needs more than hopes and dreams for a better world. It needs a good dosage of realism — and it needs to drop the intellectual quotation marks around “great-power competition.”

Dominik Wullers is a McCloy Fellow and studies international relations and security policy at the Harvard Kennedy School. He served in the German Army and most recently as an economist in the acquisition office of the German Ministry of Defense. His views reflect only his own and neither that of the German Ministry of Defense nor any other institution.

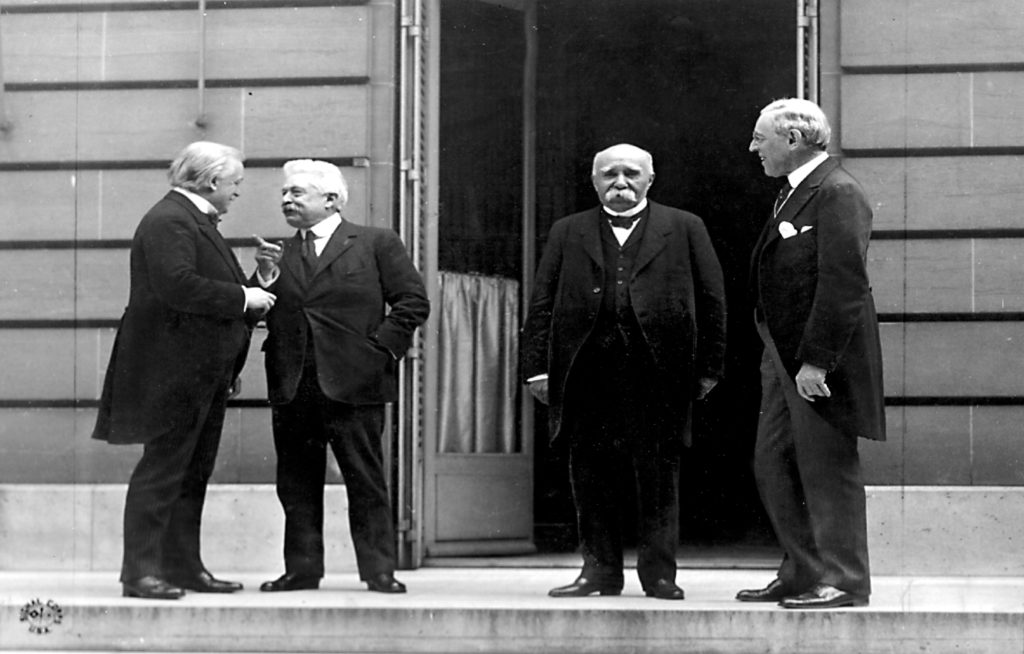

Image: Wikicommons (Photo by U.S. Signal Corps)