Join War on the Rocks and gain access to content trusted by policymakers, military leaders, and strategic thinkers worldwide.

One of the oft-voiced constraints on the longevity, or perhaps durability, of Russian power is that of its demographic decline. If there is a mainstay of wisdom in Washington, it is that Russia’s underperforming economy, and a terrible demographic outlook, mean that Russia doesn’t have a “long game.” President Barack Obama echoed this view in 2014:

I do think it’s important to keep perspective. Russia doesn’t make anything. Immigrants aren’t rushing to Moscow in search of opportunity. The life expectancy of the Russian male is around 60 years old. The population is shrinking.

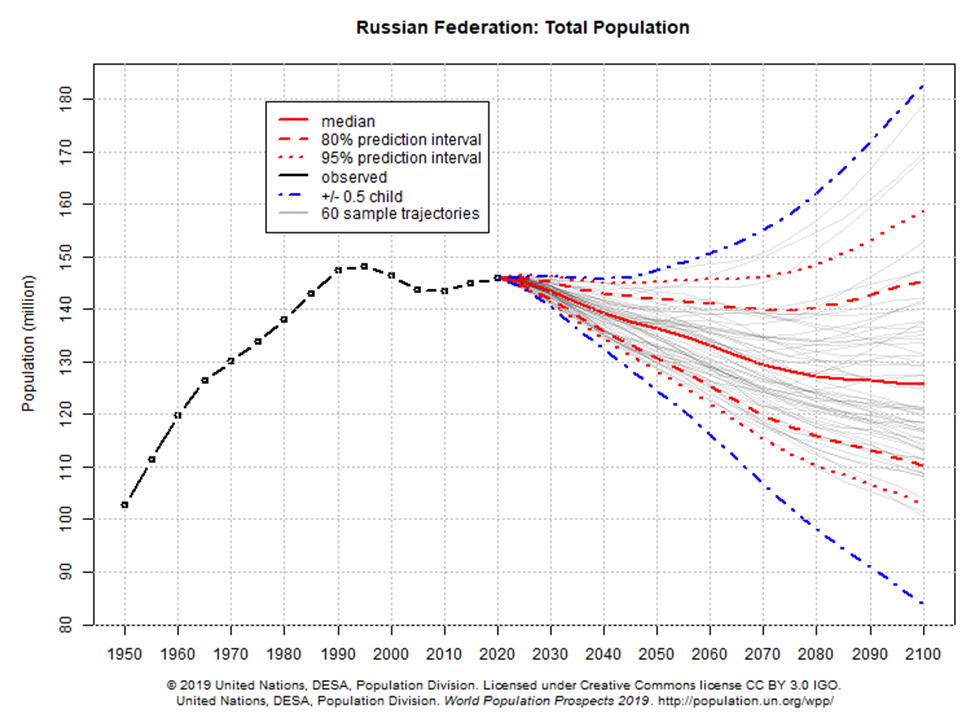

A 2019 RAND report voiced similar sentiments: “The Russian population is likely to shrink. Counterbalancing Russian power and containing Russian influence will probably not place a growing burden on the United States.” The RAND team illustrates that China’s population is also declining, but at a marginally lower rate than Russia’s. China is, of course, called the “pacing threat,” despite its looming population decline, whereas Russia is a declining power, because its population will decline somewhat faster than China’s. Such proclamations are hardly confined to Washington defense intellectuals. Joe Nye declared in 2019 that Russia’s population may fall from “145 million today to 121 million by mid-century” as part of an argument for why Russia is a country in decline. These statements are based on questionable, or dated information, playing with statistics to paint a picture more dire than exists.

First, it is not fair to take the worst-case scenarios for any country’s demographic future and advance murky numbers as though they represent the likely outcome. The median scenario predicted by U.N. demographers for Russia suggest a population decline of approximately 7 percent to 135 million by 2050 — not exactly the roughly 17 percent contraction Nye predicts. Russia does face population decline, as do many developed countries (including many American allies), but what does that mean for America’s strategic future? Will demographics prove a determinant of power in this century? And how should U.S. strategists, policymakers, and military leaders integrate the notion of demographic decline into their thinking about the long-term confrontation with Russia?

The prospective decline of Russia’s population is not only overstated but is also unlikely to substantially constrain Russian power or make the country less of a problem for the United States. Such notions are not only based on bad information, they have also become an alibi for the absence of U.S. strategy on what to do about Russia. Policymakers should not seek solace in the proposition that Russia will run out of people, ceasing to be a power of its own accord. Critically, there is much the Russian state could still do to improve or worsen the direction of Russia’s demographic profile over the coming decades. Discussions of Russia’s demographic demise are too fixated on the population size, avoiding more important questions about the quality of human capital and the relevance of population to power. The evidence suggests that Russia isn’t going anywhere, and future generations of Russians are more likely to contribute to its revival rather than its decline.

Is Demography Destiny?

Demographics are an important though often misinterpreted factor in assessing a country’s power. Hal Brands put it eloquently:

A country’s people are taproot of its power in many respects. A large working-age population serves as a source of military manpower. Far more important, a relatively young, growing and well-educated population is a wellspring of the economic productivity that underlies other forms of international influence. All things equal, countries with healthy demographic profiles can create wealth more easily than their competitors.

Nick Eberstadt, an established researcher on demographics, writes: “Although conventional measures of economic and military power often receive more attention, few factors influence the long-term competition between great powers as much as changes in the size, capabilities, and characteristics of national populations.”

Yet the conversation on demographics can tend towards the simplistic, focusing on population size rather than the qualitative dimensions that make up human capital — such as education or health. This represents a fundamental problem in strategy discussions that can at times seem rooted in a dated pursuit of land, people, and resources. In the 19th and 20th centuries, more people meant more economic output in industrial and agrarian economies that were manpower intensive. A larger population base was essential for mass mobilization armies. In large-scale industrial warfare, the country with a larger population and millions more industrial workers stood a good chance of simply attriting and outlasting an opponent with less manpower. More people meant larger armies, and the ability to replace losses. Few countries know this history better than Russia, which has historically benefitted from being the most populous nation in Europe.

At the same time, however, having more people does not readily translate into greater power. If it did, then Nigeria, Indonesia, or Bangladesh would be among the world’s strongest nations. Yet while they are more populous, they are not more wealthy, powerful, or influential than much smaller European states. A larger population is only beneficial to a country that is able to educate, employ, and leverage that potential. In many cases, a large and rapidly growing population generates immense social pressures and challenges faster than it does power. Michael Beckley argues that standard indicators exaggerate the power of populous countries like China, in his 2018 article “The Power of Nations: Measuring What Matters.” Thus, while we should not forget Stalin’s adage that “quantity has a quality of its own,” it is equally important to consider that what matters most is what countries do with their human capital rather than just how many people they have on the books.

Population matters less for military power. Wars are no longer fought by mass mobilization armies; instead, technology has multiplied destructive power such that the soldier is increasingly alone on the battlefield. As firepower and range have increased, the need for manpower has decreased compared to the great power conflicts of the 20th century. Quantity and mass remain important in modern warfare, but few countries are able or willing to support sizable forces. Military expenditure and political will are today’s defining constraints on the size of standing armies in middle- and high-income countries, more so than the actual availability of people to serve. Russia remains one of the few exceptions in this regard, maintaining a high degree of defense spending and increasing the size of its military over the past decade at a time of limited manpower availability.

No less significant is the modernization of nuclear weapons by the world’s great powers, chiefly held by the United States and Russia, which has always made doubtful the proposition of a prolonged conventional conflict between the main nuclear weapon states. Strategic and non-strategic nuclear weapons represent a demographic equalizer, whereby no matter what happens in Russia’s demographic future, it will still be able to inflict unacceptable damage to the United States or Europe.

Russia’s Demographic Challenge

Russia’s demographic decline is borne of two factors: a demographic crisis in the late 1980s and 1990s, the aftereffects of which will create a second demographic dip in the coming decades, and an unusually high mortality rate. Not enough Russians were born those decades, and those that were born then are dying faster than people of the same age in other industrialized European nations. Although Russia is a major net beneficiary of labor migration, which helps arrest population decline, immigration cannot compensate for the expected population dip.

How important is this issue for Moscow? Well, for President Vladimir Putin, it’s among his top priorities. He has frequently emphasized population growth as an important factor in rebuilding Russia’s global status. In 2017, Putin stated, “Demography is a vital issue that will influence our country’s development for decades to come.” Through countless speeches, including the latest January 15th Federal Assembly address, he has emphasized the demographic challenge. The presidential order, signed in May 2018, delineating national goals and strategic priorities through 2024, lists achieving stable population growth as its first objective. Indeed, years of effort and investment has arrested or stabilized some of the worst indicators, leading to a dramatically improved picture compared to the dire predictions based on data in the mid-2000s.

Despite appreciating the stakes, Russian leadership will struggle to address Russia’s demographic challenges. Such difficulty is in part due to the fact that since 2014, Russia has engaged in a host of foreign policy gambits that are visibly exacerbating the demographic problem — from lower birth rates due to poor economic conditions to urban Russians choosing to leave the country. Russia’s economic recession beginning in 2013 and sanctions resulting from the confrontation with the West have served to increase a steady exodus of urban Russians, which began in 2011–2012 when Putin “returned” as president.

As a consequence, post-2015 policies have reduced the net benefit of migration, while squandering an opportunity to pour resources into arresting Russia’s demographic decline through policies intended to boost birth rates. All of this means that Russia’s demographic policy faces strong headwinds today, created in part by Russia’s foreign policy choices, and as time runs its course, may face harsher realities in the 2040s and 2050s. The outlook will vary considerably depending on the policies that Russia chooses to implement.

Lies, Damned Lies, and Statistics

Russia’s demographic trends improved considerably between 2000 and 2015, but the country faces a coming generation that will have substantially fewer women of child-bearing age, an aftershock of the crisis in the 1990s. This means that despite numerous improvements to the overall health of the Russian people, arresting the crisis of the 1990s, Russia is still facing an unavoidable long-term decline in total population.

In 2017, life expectancy became the highest it has ever been in Russia or the Soviet Union, at 72, although quite a lot shorter for men than women. This puts Russia at the bottom of life expectancy for developed Western countries, but it is a marked improvement from the previous decade. Average male life expectancy is still quite low, in large part because of alcohol-related deaths. Yet alcohol consumption has fallen by more than a third since 2006, and one study argues that the proportion of men dying before 55 has been reduced by 37 percent. The fertility rate has climbed considerably, converging with that of the United States. This rate is still below the population replacement rate of 2.1, but Russia has made strides in recovering from the nadir of the late 1990s. Deaths are down, infant mortality is less than half of what it was 30 years ago, and a host of health indicators have improved from that period to 2015. Unfortunately, Russia’s mortality rate remains far too high by European and international standards, with men representing the most at-risk population.

Statistics on human capital and productivity also tell a more positive story. The U.N. Human Development Index has continued to increase Russia’s rating, from .734 in 1990 to .824 in 2018. Meanwhile, the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development shows the growth rate in Russian labor productivity as being much higher than that of the European Union. These are crude measures, but they indicate improvements in the quality versus just quantity of human capital in Russia.

Yet Russia is a country that is still dealing with the aftereffects of the decline of the Soviet Union and the demographic crisis that followed. The current challenge is a steady aging-out of the working population, losing as many as 600,000 annually over the next six years. The replacements for aging Russian workers were not born in the 1990s, and hence they are not here today to take up jobs in the Russian economy. This is the consequence of the mass emigration, social, and economic crisis of the 1990s that still haunts Russia. In the long term, Russia is likely to go from a population of around 146 million today to perhaps 135 million in 2050, according to the 2019 United Nations World Population Prospects report. The World Bank is more pessimistic, suggesting it might be as low as 132 million. This is a 7.5 percent to 9.5 percent decrease, representing median scenarios, while worst case (but least probable) estimates take those expectations lower towards a fall of 12 percent.

However, an authoritative report published by the Russian Presidential Academy of National Economy and Public Administration (RANEPA) painted a much more dire scenario. According to their work, with changes in policies on fertility, mortality, and migration, an inertia-based scenario could take Russia’s population down to 113 million by 2050. This was the source of the dire predictions for a “depopulation” of Russia in the coming decades, but it was calculated in 2009, based on 2005 data. The evidence is clear that the original inertia scenario, which predicted a decline to 140 million by 2020, has not developed. The net Russian population only began shrinking in 2019 and is still above 145 million. Russia’s statistical service’s latest figures also offer an average prognosis of decline to 143 million by 2035 — with a worst case scenario of 135 million, and an optimistic one of 149 million.

RANEPA’s figures, when updated in 2015, showed a different inertia scenario that places the Russian population at around 128 million by 2050. Given the current trajectory, it appears more probable that Russia’s population decline will end up between the more optimistic scenarios and the inertia scenario, landing somewhere in the 130 to 135 million range by 2050. This study emphasized that Russia has a unique window of opportunity right now, because it currently has “one of the world’s highest shares of population in the active reproduction and working ages (15-60 years). This includes a high percentage of people in the prime working and parenting ages (20-40).” In their assessment current Russian efforts to address fertility, mortality, and migration, fall short of what will be required to achieve more positive scenarios.

Much of the conversation on Russia’s demographic prospects also misses an important fact: Russia, like the United States, maintains its population in part through migration. Russia is the principal labor market for the former Soviet space, benefitting from net labor migration. Western media outlets are replete with sensational headlines about educated Russians fleeing the country in recent years. Russian emigration has increased considerably since 2012, and many have argued that those emigrating represent the country’s creative class. Indeed, Russia’s statistical agency Rosstat does show 377,000 departing from the country in 2017. However, the very same statistics show that 589,000 immigrated to the country in that year, for a net gain of about 211,000.

The brain drain effect appears overstated. Most in and out migration is likely migrant labor from Central Asia, rather than entrepreneurial geniuses emigrating en masse. Russia is a significant beneficiary from immigration, which in part helps compensate for its own fairly low birth rates. There is unfortunately indistinct math on how Russian émigrés are counted according to Rosstat, which understates the number of Russians emigrating because it doesn’t count them as having left unless they cancel their registration in Russia.

The Demographic Price of Russia’s Foreign Policy

Not only does Russia’s period of imperial collapse still cast a long shadow, but the demographic recovery from 2000 to 2015 also faces a second challenge from Russia’s economic and political crisis of recent years. Russia is in economic stagnation; that is, with anemic GDP growth of ~1.3 percent in 2019, well below the global average. Economic recession and uncertainty have a naturally negative impact on family planning and birth rates. Russia’s birth rate has flattened out since 2014 and begun to decline again, sinking to 2011 lows. Deaths still exceed births, and even with immigrants, Russia’s population has entered a steady state of decline in part because of underlying economic and political conditions. The problem is not lost on the government, even though the consequences of this second dip may not be felt until the mid-2030s. State policies have helped avoid worst case scenarios, but they cannot avert the inevitable.

Although mortality had been improving considerably from 2005-2013, mortality rates have Russia’s deputy prime minister for social and health policy, Tatyana Golikova, made clear in the spring of 2019 that mortality trends have changed to a negative outlook. Several Russian regions have witnessed an increase in mortality rates in 2018, which has contributed to the country’s first recorded population decline in a decade, falling by about 87,000 last year. Problems in the healthcare system are particularly acute in Russia, from a lack of clinics and doctors, to shortages of medicine. The government’s efforts to tackle mortality face reversals in regions worst hit by economic problems. As poverty increases, mortality rises, and birth rates again decline. Thus, the Russian state must now address the current crisis with new measures, while at the same time retaining focus on the long-term strategic problem of population decline.

There is a worrisome potential relationship between demographics and Russia’s foreign policy today, including the long-standing practice of “passportization.” During his annually televised question and answer session in 2018, Putin suggested that one of the solutions to the demographic problem is liberalizing citizenship policy to integrate Russian compatriots. The implied message was that Moscow sees refugees from conflict as a potential positive in light of the demographic challenges the country faces — compatriots, or those Russia considers to be part of the Russian world (Russki Mir), are part of the solution.

In the long run, demographics, not geopolitics, may prove Putin’s chief error in undertaking a confrontation with the United States. Undoubtedly, Moscow can keep up the contest, but it will come with a strategic price tag for Russia’s future during a crucial decade when the country needs to focus resources on its demographic problem. The population structure will change in the 2030s such that a second demographic “dip” will become more pronounced, rendering later efforts less effective. There is an inherent tradeoff between Moscow’s prioritization of the country’s demographic health and its geopolitical pursuits, and this does not seem to be accepted by the national leadership.

Military and Manpower

The Russian military has revised and increased its force structure since 2013 with new divisions and regiments. This naturally raises the question: Who exactly will man many of the new units being created in the Russian armed forces? The picture is far from rosy, and the units will undoubtedly have formations based on a partial mobilization structure, but the Russian military is in much better shape than it has been since the collapse of the Soviet Union and is certainly at its highest levels of readiness in decades. Increased birth rates starting in 2000, and improvements to health standards from 2000-2015, mean that manpower availability is going to increase, likely until 2033, as will the overall pool of those available for military duty (ages 18 to 27).

Perhaps remarkably, the Russian armed forces have been increasing in size over the past five years, all while facing a constrained availability of manpower and higher economic competition for those they would seek to recruit as volunteer servicemen. The available male serving population was in decline from 2008 to 2018. Yet despite being under such stringent conditions, the Russian armed forces expanded to perhaps somewhere near 900,000 in overall size, and the contract share of the force is around 394,000, or more than half of those enlisted. This means that the number of conscripts Russia’s armed forces need every year has declined substantially and will continue to drop. The Russian Ministry of Defense also changed its policy in 2018 to allow conscripts to elect to perform two years of volunteer contract service instead of one year of compulsory duty.

Tackling draft evasion and corruption has also allowed the Russian military to get more out of what they have. Russia’s draft board, or Voenkomat, has spent years fighting the pervasive problem of those seeking to evade the draft by purchasing health exclusions or disqualifications. Over the next 14 years, there will not be substantial pressure on manpower availability for service. Afterwards, the armed services will be operating in a much more competitive environment, with declining manpower availability starting around 2033. Additionally, the relevance of manpower constraints as they pertain to warfighting beyond the 2030s remains in question, as modern militaries grow even stronger in firepower, technological force multipliers, and use of autonomous systems, depending more on the quality rather than the quantity of personnel deployed. Plus, Russia will always find enough people to man its arsenal of strategic and non-strategic nuclear weapons.

Implications for Great Power Pursuits

The remaining question is whether Russia will face a classic “guns versus butter” choice, as the working population shrinks, forcing the state to choose between military modernization and pensions. Brands predicts:

Russia will face Hobson’s a choice between pouring scarce resources into old-age pensions and inviting the political tumults that austerity could easily bring. Nuclear weapons and the capacity to create mischief through information warfare will keep Moscow in the game, but Russia’s underlying geopolitical potential will continue bleeding away.

So far, this prediction is not coming true. Russian resources are not particularly scarce, and it’s unclear what “geopolitical potential” has been bleeding away. Such sentiments are common among defense intellectuals and international relations theorists, but the evidence behind these arguments often fails to impress. If theory checks in with practice, it will find that Russia’s GDP continued to grow, as did labor productivity, while the population contracted in 2019. The argument that Russia is in decline is largely premised on a puzzling comparison between Russia’s influence today and the Soviet Union, which broke into 15 countries almost 30 years ago.

Moscow is already addressing the question of pension reform, and has weathered the resultant political tumults, while at the same continuing to spend sizable sums on its military potential. Thus far, the Russian government has decided to sequester defense spending, decreasing it slowly over time, while imposing austerity on social benefits by increasing the retirement age in 2018. Moscow is reconciling these priorities by choosing to spend less on both, taking a somewhat opposite route than what Washington might have taken. Hence, the U.S. government’s debt-to-GDP ratio stands at 106 percent, whereas Russia’s is one of the lowest in the world, at around 15 percent. In 2019, Russia’s net public debt fell to zero as the country amassed sizable foreign exchange reserves relative to its rather small amount of debt.

Much of what strategists perceive to be inevitable is actually contingent, a function of choice and strategic investments. Demographics advantage the United States, but they do not doom America’s great power adversaries, nor should they confer a general ease that others will face choices America does not. Russia’s demographic outlook is a complex question, but the facts suggest that there is no imminent collapse facing the country. In recent years, that future appears much less dire than it did, but clearly bleaker than it has to be. The extent of Russia’s long-term demographic decline remains in question given how much of the problem can be redressed or exacerbated by government policies. One cannot exclude a change in the nature of Russia’s political or economic system over time, which may seem a distant proposition today, but is not unrealistic when looking out to the 2030s or 2040s.

Instead of talking about Russia’s or China’s uncertain demographic future, U.S. policymakers should pay closer attention to the demographic situation of their own allies, like the Baltic states, which is more dire. Latvia’s and Lithuania’s populations have been in constant decline since 1991, and Ukraine’s is particularly problematic. Russia’s demographic picture should be compared to the countries the United States is concerned with defending from Russia. As Nick Eberstadt explains:

[T]he EU and Japan have both registered sub-replacement fertility rates since the 1970s, and their fertility rates began to drop far below the replacement level in the 1980s. In both the EU and Japan, deaths now outnumber births. Their working-age populations are in long-term decline, and their overall populations are aging at rates that would have sounded like science fiction not so long ago.

Given that the United States is most likely to fight in contests abroad, on the foreign soil of countries to which it extends deterrence, there is a more important question: How do allied demographic futures compare to those of our adversaries in their regions? The short answer is not favorably. As a consequence, the overall burden for the United States of confrontation, economic competition, and deterrence is only going to increase in the coming decades.

The core Russian problem is not demographics, but the fact that the economy and the political system are unable to tap into the talent and human potential of that country. Russia has the requisite attributes to be far more powerful and influential than it is today, with fewer people. The country endures as a great power in the international system despite the best efforts of policy wonks and defense strategists to wish it away. Adam Smith’s adage that there is a “great deal of ruin in a nation” serves well here in setting expectations. Russia’s comparative weakness should not be confused for an inability to play an important role in European affairs, or check U.S. foreign policy abroad. Russia does have a long game, but it is not clear that Washington has a long game for dealing with Russian power in the world.

Michael Kofman is director and senior research scientist at CNA Corporation and a fellow at the Wilson Center’s Kennan Institute. Previously he served as program manager at the National Defense University. The views expressed here are his own.

Image: Kremlin