Join War on the Rocks and gain access to content trusted by policymakers, military leaders, and strategic thinkers worldwide.

Beijing’s geopolitical moves continue to obfuscate its larger designs, surprise observers, and render the United States and its allies reactive. The prospect of a Chinese naval base in Cambodia offers a case in point.

This issue — seemingly obscure and inconsequential to many observers — made the news in late 2018 when American Vice President Mike Pence raised it in a letter to Cambodia’s increasingly authoritarian leader, Hun Sen. Subsequently, Hun Sen dismissed media reports that China sought a naval base in Cambodia as “fake news.” In repeated denials, he proclaimed that Cambodia’s constitution prohibits any foreign country from setting up military bases within the country’s sovereign territory.

Recent satellite imagery depicting an airport runway in Cambodia’s remote Koh Kong province. Its length is similar to those built on the Spratly Islands in the South China Sea and it is long enough to support Chinese military reconnaissance, fighter, and bomber aircraft. Source: EO Browser.

And yet, questions remain. Recent commercial satellite imagery shows that Union Development Group, a Chinese-owned construction firm, has been rushing to complete a runway in Cambodia’s remote Koh Kong province on the southwestern coast. It appears long enough to support military aircraft and matches the length of the runways built on the Spratly Islands in the South China Sea to support military reconnaissance, fighter and bomber aircraft. Moreover, given the amount of political and economic support Hun Sen has received from Beijing, his independence seems increasingly doubtful.

However, these accusations and denials prevent a meaningful discussion of what the establishment of such a base would mean and what an appropriate response to such an eventuality would look like. They also obscure the question of why Beijing would seek to build a military base in Cambodia.

For Beijing, the strategic dividends of acquiring a military base in southeast Asia are numerous: a more favorable operational environment in the waters ringing southeast Asia, a military perimeter ringing and potentially enclosing mainland southeast Asia, and potentially easier and less restricted access to the Indian Ocean. These benefits are not all of equal value to Chinese strategists, nor does China need any of them immediately. But the logic of Chinese expansion suggests that sooner or later, Beijing will need such a military outpost in southeast Asia, and Hun Sen’s Cambodia presents especially fertile geographic and political soil.

While Hun Sen currently denies that he would allow the rotational presence of the Chinese military or a more permanent Chinese military base on Cambodian territory, strategy often deals in the realm of the possible. Proactively dealing with this challenge requires understanding the Chinese template for developing military bases, thinking through the strategic effects of such a base in Cambodia, and developing options to forestall such a development.

The Chinese Template

Forming a picture of what a Chinese military outpost in Cambodia could look like and how quickly one could become operational is not an act of wild speculation. Chinese efforts elsewhere provide evidence of a simple template. In the South China Sea, in Djibouti, and in other locations in the Indian and Pacific Oceans, Beijing has followed a similar pattern in which denial precedes further action and helps to veil the full extent of Beijing’s aims.

The Chinese template for construction of new military basing was on full display in the South China Sea, where Beijing pursued the quick buildup and rapid militarization of facilities in the Spratly Islands. Chinese officials denied that plans existed for base construction even as Chinese fisherman and private construction companies began to undertake such efforts. Once base construction was underway, Chinese officials claimed such actions were undertaken for humanitarian purposes and continually promised they would not militarize the South China Sea. Once militarization of these facilities was complete, Beijing again shifted its explanations, noting that the military bases were purely defensive in nature. Finally, the Chinese military began building hangars and infrastructure required to deploy fighter jets and other military aircraft to these islands, just as they installed anti-ship cruise missiles, surface-to-air missiles, and military jamming equipment.

Djibouti showcases a second example of this template, as Beijing established its first overseas military base in the crowded East African country. As China expands the reach of its blue-water navy, this base has allowed Chinese naval ships to replenish stores, make repairs, and play a positive role in multinational counter-piracy operations against Somali pirates. However, Beijing uses its military base in Djibouti for more nefarious purposes, as well. Chinese personnel have stepped up intelligence collection efforts on American forces stationed nearby and may be using ground-based lasers to blind U.S. military pilots in local airspace. Observers have also raised questions about Djibouti’s growing indebtedness to Beijing and increasing Chinese influence on its leadership.

Djibouti represents the most developed case of Chinese military basing abroad, but there are similar dynamics playing out elsewhere. Pakistan, Sri Lanka, and the Pacific island state of Vanuatu all possess the potential for deep-water ports in strategic locations for a Chinese navy looking to secure its shipping routes, project power outward, and complicate America’s access to key areas in the Indian and Pacific Oceans. In each country, Beijing embarked on a long-term courtship premised on generous loans and aid packages, while focusing on projects that support both civilian and military use.

Beijing’s playbook in each case involves investment in a country’s critical infrastructure, acquisition of a significant piece of waterfront territory by a Chinese company, and assertions by Chinese officials that the activity is purely commercial or humanitarian. In actuality, the denials typically precede future actions toward Beijing’s true aims.

The pattern of Chinese actions in Djibouti, Pakistan, and Sri Lanka indicates the real potential for a similar process to play out in Cambodia. This is especially true given the growing convergence between the way that Hun Sen defines Cambodian interests and Chinese foreign policy. Hun Sen has helped expand Beijing’s local and regional ambitions in exchange for political support and diplomatic backing from Beijing, closer military cooperation, and more development aid, concessional loans, and investment. While there is widespread, if quiet, anger among ordinary citizens who have seen little benefit from their government’s growing subservience to China, this counts for little in a country with an increasingly repressive leader. Phnom Penh may not prove able to resist a Chinese basing ploy, given the significant political and economic leverage Beijing possesses over Hun Sen. In fact, Cambodia might not even attempt to resist as according to Hun Sen, China and Cambodia are now like “siblings who share a single future.”

Shifting Southeast Asia’s Strategic Landscape

What value would the Chinese find in the establishment of a military base in Cambodia? Its southwestern coastline does not lie directly on any of China’s major maritime trading routes, so it offers seemingly little by way of securing sea lines of communications. Cambodia does not straddle the route to Chinese energy sources in the Indian Ocean and the Persian Gulf. Further, given the large military bases on China’s southern coast, Chinese forces operating in the Spratly Islands would gain little from a base in Cambodia.

Yet there are several ways in which a Chinese base in Cambodia could have an outsized effect on the strategic landscape of the region. First, this base would change the military dynamics of the waters around Southeast Asia. Such a base would not only significantly extend Chinese power projection capabilities within the region, but it would also grant Beijing greater ability to harass American and allied military vessels transiting the area and threaten American access to allied countries like Thailand. A Chinese naval base in Cambodia would also allow Beijing to challenge any military vessels coming through the South China Sea from two directions, instead of only from the Spratly Islands.

Moreover, a military facility in Cambodia would effectively complete a triangular perimeter around Southeast Asia, given existing Chinese military bases in the Paracel and Spratly Islands. As such, the military implications of a Chinese base in Cambodia would pale in comparison to the potentially profound political effects. A Southeast Asia more fully enclosed by Chinese military forces would engender a more closed political space and a more deferential set of foreign policies in affected countries. The sovereign states of Southeast Asia have thus far avoided becoming China’s tributary states in no small part due to their possession both maritime and mainland access — and egress — points. If a Chinese military base in Cambodia allowed Beijing to restrict that access, many states would make the calculation that they had little choice but to follow Beijing’s lead.

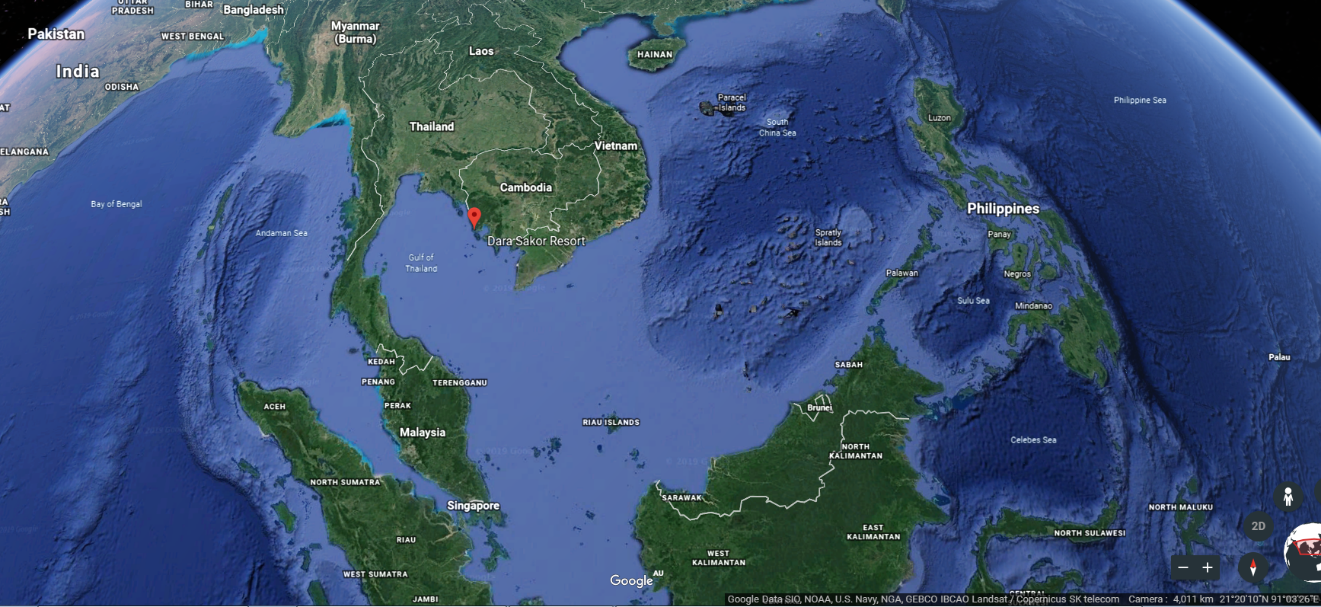

A Chinese military base in Cambodia would provide Beijing a more favorable operational environment in the waters ringing southeast Asia, a military perimeter ringing mainland southeast Asia, and potentially less restricted access to the Indian Ocean. Source: Google Earth.

In addition to present concerns, there are also future possibilities to consider. A decade ago, few observers would have predicted that the creation of enormous manufactured islands by Chinese sand dredgers in the South China Sea could have so dramatically altered the strategic picture today. Another similarly ambitious project would become logistically easier with the establishment of a military base in Cambodia. A canal across Thailand and into the Indian Ocean has been discussed for more than a century, and given China’s Maritime Silk Road initiative, it is now receiving increased attention.

A cross-Thailand canal would shorten China’s path into the Indian Ocean by providing multiple points of entry to that body of water. By offering another access point into the Indian Ocean, it would mitigate Chinese fears about the Malacca Straits, a chokepoint that could be closed or blockaded to drastically decrease Chinese access to energy (a scenario commonly referred to as the “Malacca Dilemma” by Chinese military planners). An alternative route would likely increase the supply, logistics, and security demands of the Chinese navy, thereby necessitating even more bases in and around the Indian Ocean. This scenario should be of particular interest and concern to India.

Getting Ahead of the Curve

Despite repeated Cambodian denials that it will host a Chinese military base, realistic planning dictates that U.S. policymakers and their counterparts in the Indo-Pacific should consider several options in advance to respond to potential stages of base construction.

First, policymakers must get ahead of the issue, rather than simply react to it. This is a larger challenge for policymakers dealing with Beijing’s creeping expansionism, which features incremental advances calculated not to trigger a significant response and actions intended to remain ambiguous until they are presented as a fait accompli.

Second, because Hun Sen is sensitive to charges of undermining Cambodian sovereignty, policymakers from concerned nations should focus on providing information to the Cambodian people about the secret sale of 20 percent of Cambodia’s coastline, the displacement of thousands of Cambodians, the use of Chinese workers on projects that Cambodians themselves could do, and the environmental degradation and extraction of Cambodia’s natural resources. While Cambodia’s information space is highly monitored and constrained, opportunities exist to better support local media and circumvent governmental regulations. Increasing the Cambodian public’s awareness of the potential Chinese base would improve the chances that Hun Sen will honor Cambodia’s constitutional prohibition against hosting foreign troops to avoid domestic political blowback.

Third, the United States should encourage concerned countries to take the lead in opposing a Chinese base and prepare options to respond to base construction, should they prove unable to stop it. After all, this is not a cause of concern solely or even primarily for the United States. It affects the security, prosperity, and political independence of multiple countries, particularly those in Southeast Asia. This issue needs attention first and foremost from those in the region, starting with Thailand and Vietnam. Regional leaders from Bangkok to Hanoi need to make their voices heard on how a Chinese base in Cambodia would affect their sovereign interests. Regional countries must also consider what types of security equipment and arrangements they would require to offset Chinese advantages created by a new base in Cambodia.

Southeast Asia need not take sides between American and China — but it should work to maintain its independence. Given the outsized implications for Southeast Asia, regional policymakers possess an opportunity to communicate their concerns, offer Beijing an opportunity to allay such concerns, and shape the political dynamics in their backyard.

The strategic implications of a Chinese base in Cambodia would also affect the interests of other regional powers, such as India and Japan. In 2018 alone, Japan purchased $1.6 billion worth of Cambodian goods, an increase of 27.3 percent from 2017. In 2016, India replaced Canada as the ninth-largest source of foreign direct investment in Cambodia. Delhi’s investments have been more modest in Cambodia to date, but the projected growth of India’s economy and its investments in Southeast Asia suggest that it could become a significant economic partner for Cambodia in the future. Further afield, the European Union also possesses an interest in Cambodia. In 2017, European Union nations bought $5.8 billion worth of goods from Cambodia, or about 40 percent of its exports. The European Union is already leveraging its preferential trade deal with Cambodia to exert pressure on Phnom Penh’s human rights record. Given these economic links, the European Union, Japan, India and others can make the case to Cambodia that a decision to accept a Chinese military base would not be well received.

Finally, this issue should reinforce the need for the United States and its allies to think strategically about the region as a whole. In this case, that means thinking geographically. The United States and its democratic partners hold the exterior lines of the broader Indo-Pacific region from Japan and Taiwan in the east to Australia and New Zealand in the south and India in the west. China’s current strategy is geared toward hardening its interior lines in Southeast Asia and outflanking the aforementioned exterior lines with bases in Africa, the Indian Ocean, and Oceania. While military outposts in these separate areas may seem unconnected, failing to see Beijing’s larger design hampers the ability to act in a strategic fashion.

The logic of Chinese expansion suggests that sooner or later Beijing will need such a military outpost in Southeast Asia, and the growing convergence between China and Hun Sen renders the prospect of a military base in Cambodia more likely.

A Chinese military outpost on Cambodian territory would rapidly shift the strategic landscape of Southeast Asia to the detriment of both the United States and its regional allies and partners. Forestalling this outcome requires concerned states to proactively shape the strategic environment by calling attention to what has already occurred, encouraging greater engagement by regional actors and local powers, and approaching the region from a broader perspective.

Charles Edel is senior fellow at the United States Studies Centre at the University of Sydney. Previously, he was associate professor of strategy and policy at the U.S. Naval War College, and served on the U.S. Secretary of State’s policy planning staff from 2015 to 2017. Most recently, he is the co-author of The Lessons of Tragedy: Statecraft and World Order.