Join War on the Rocks and gain access to content trusted by policymakers, military leaders, and strategic thinkers worldwide.

Over the past 15 years drones have become an accepted tool of U.S. military policy. These platforms have become so popular that remotely piloted, unmanned, and increasingly autonomous weapon systems have been central to the Department of Defense’s third offset strategy, which calls for increasing investments in these technologies to maintain America’s technological edge. Conversations surrounding the potential of these new technologies often focus on their capabilities and ability to increase combat effectiveness. Yet the introduction of these new platforms raises a host of other interesting questions that relate not only to their legal and ethical implications, but also issues of human-machine relationships. In a December article in Foreign Affairs we described the results of a research project that focused on this latter issue in particular, highlighting trust issues that ground personnel have voiced when using unmanned aircraft in a number of combat scenarios. In response to our piece, Jon Askonas and Colby Howard wrote an article for War on the Rocks that raised a number of concerns about our findings. We appreciate the authors’ engagement with our research.

Before addressing the more interesting question that Askonas and Howard raise, it is important to clarify an important source of confusion that appears to have arisen from our article. In the article, we described the results of a survey experiment that we issued to joint terminal attack controllers (JTACs) and joint fires observers (JFOs) regarding their preference for manned aircraft and unmanned aerial vehicles in a variety of different scenarios, and then outlined some policy implications of the research. The survey that we described in our initial article was designed to ascertain the beliefs and perceptions of JTACs and JFOs regarding their preference to use manned or unmanned aircraft for air strikes. The core puzzle driving the research was our quest to understand the source of these perceptions. Were these perceptions driven purely by the capabilities of the manned or unmanned aircraft? And if not, what else might explain this group’s attitudes towards these strike platforms? Crucially, our research project was not focused on establishing whether these perceptions were “correct” or accurate representations of reality. The core puzzle that motivated this research is not whether manned, remotely piloted, or completely autonomous weapons systems are “better,” but instead what drives preferences for these platforms.

As a result, we do not question that “drone pilots are deeply engaged in their missions,” as Askonas and Howard note, nor that of their missions “there is none they are more passionate about than close air support.” Moreover, we are well aware of the research on post-traumatic stress disorder and depression among drone pilots and that there is a human being making important and difficult decisions. However, none of this undermines the fact that interviews of approximately 450 JTACs and JFOs across all services revealed a set of different perceptions on the ground. Without taking a position on the merits of these perceptions — and rather than simply dismissing them as “skewed” or erroneous — we chose instead to try and understand why they existed in the first place. We believe that these perceptions have implications beyond this particular debate for the third offset, and more broadly the future of warfare.

Second, Askonas and Howard implied that we hold positions we do not hold and made recommendations we did not make. For example, we do not recommend that, because of these findings, pilots should “risk their lives solely to inspire confidence in troops on the ground.” Instead, the point of our article – and the research more broadly – is to highlight human-side barriers to the potential use of unmanned aircraft in certain types of missions. Whether these barriers will change is addressed in more detail below, but at no point did we recommend that pilots risk their lives just to inspire “warm feelings,” as the authors suggest.

In order to move the conversation forward, we would like to highlight one of the more interesting points that the authors raise — the role of experience in shaping perceptions of effectiveness. Our research suggests that there is a difference between confidence — or the belief that an unmanned aircraft can effectively complete a mission — and trust — or the willingness to use an unmanned aircraft to complete a mission. What we were unable to find in our research (perhaps because confidence in capabilities was not yet high enough) is at what point confidence in these machines becomes high enough to create trust.

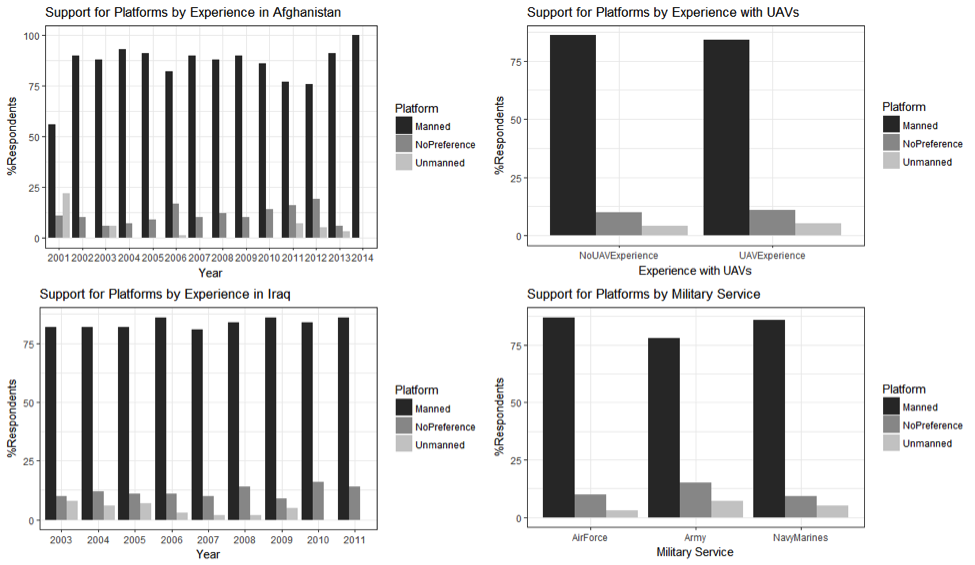

We tried a variety of survey means to try and understand when and how experience with unmanned aircraft could generate trust. First, we asked the JTACs and JFOs about their experience in general in combat: Had they served in Afghanistan or Iraq? (see graph below with a series of demographic variables). We found no statistically significant correlation between those experiences and support for platforms. Then, we asked more specifically: Have you ever controlled kinetic-capable (able to employ ordnance) unmanned aircraft in combat? Once again, we found no statistically significant difference in preference for manned versus unmanned aircraft.

As Askonas and Howard alluded to in their piece, there are some specialties within this sample — in particular special operations combat controllers — who have the most experience with unmanned aircraft. We did not ask our respondents to identify themselves as part of special operations units because we were conscious of security concerns within this community. However, we did ask respondents, “in general what percentage of your controls have been with manned aircraft and what percentage with unmanned aircraft?” This allows us to see if those with more unmanned controls by percentage would be more likely to prefer unmanned systems. The average respondent reported only 20 percent of their controls were with unmanned aircraft. We therefore parsed out those respondents that had an above-average percentage of unmanned controls. Would that translate to a greater preference for unmanned aircraft? We did not find a statistically significant difference between the two populations (the p-value for our t-test was .308), but we did find a small increase in preference for unmanned aircraft in our more experienced group. This suggests that, while not yet significant, more controls experience could increase trust for unmanned systems.

Like Askonas and Howard, we thought that the more interaction these controllers had with both manned and unmanned pilots, the more likely they would be to support either of those platforms (see, for example, our previous work on service preferences for air-to-ground aircraft). In order to explore this personal relationship hypothesis, we asked our survey takers how often “prior to the control they had face-to-face contact with the manned pilot or aircrew” and similarly what percentage of the time “prior to the control they had face-to-face contact with the unmanned pilot or sensor operator.” We then asked the same questions about how often the controllers talked via phone with the pilots of these different platforms. We thought that the more time they spent interacting personally with any of these pilots, the greater their trust and preference would be for these platforms. On average, we found that controllers had face-to-face contact with a manned aircrew 12 percent of the time, and unmanned 6 percent of the time. The rate of interaction was greater by phone, but still controllers reported approximately double the percentage of contact with manned aircrew than those piloting remotely (30 percent manned and 13 percent remotely piloted aircraft). Did those who had greater than average interaction with drone pilots have greater preference for unmanned aircraft? Again, we found no statistically significant difference in preferences for pilots who had greater than average face-to-face or phone/video teleconference call interaction with remote pilots. However, the difference in support for unmanned was almost significant (p=.1146) and we found preferences for unmanned, as well as those who had no preference, double.

Finally, we readily acknowledge that our data and the findings that follow are necessarily limited by the time frame of the survey and the technology available at the time. Our survey and interviews started in 2014 and completed in early 2015. As a result, our research represents a “snapshot” in time of a snowball sample of JTAC and JFO perceptions of unmanned aerial vehicles. This time differential may well explain why our findings differ from the anecdotal evidence presented by the authors. It is also why more work needs to be done to understand the human side of human-machine integration. Emotional responses to machines or weapons are not only not irrational, they are extraordinarily important mechanisms that human beings use to process information and make decisions in the fog of war.

Will these perceptions change as Askonas and Howard suggest? At what point — and through which mechanisms — might we expect this to happen? These seem to be the more interesting questions on the table, and ones that we hope will motivate future research. Our data suggests that, while these preferences are strong and found across many demographics, they can change. While statistically insignificant, we did find increases in preference for unmanned aircraft when controllers had more experience with them and when they had greater interaction with the pilots. This suggests that there are tactics, techniques, and procedures that can help solve some of the trust problem.

These are small examples that lead to bigger questions about what policies, capabilities, and training can help convert user confidence in machine-integrated platforms into trust in wartime. Is it in engineering solutions like increasing sensor capabilities or communications fidelity? Is it about the geographic positioning of forces — for instance, forward deploying remotely piloted aircraft pilots for better line of sight radio communications? Or is it about training and increasing interaction with unmanned systems during ground exercises? What if JTACs or JFOs were able to control unmanned platforms from the battlefield? These are potential solutions to the trust problem that we need to explore, test, and finally integrate into future warfare strategies. Indeed, a number of analysts and scholars are already engaged on exactly these issues, and we hope that others will follow.

Julia Macdonald is an Assistant Professor at the Korbel School of International Studies, University of Denver. Her work on coercive diplomacy, foreign policy decision making, and U.S. military strategy and effectiveness has been published in the Journal of Conflict Resolution, Journal of Strategic Studies, Foreign Policy Analysis, Armed Forces and Society, and online in various policy outlets.

Jacquelyn Schneider is an Assistant Professor at the U.S. Naval War College. Her work on national security, technology, and political psychology has appeared in Journal of Conflict Resolution, Strategic Studies Quarterly, Foreign Affairs, Washington Post, Bulletin of Atomic Scientists, and War on the Rocks. The views presented here are hers alone and do not represent those of the Naval War College, the U.S. Navy, or the Department of Defense.

Image: Air Force/Shannon Collins