Join War on the Rocks and gain access to content trusted by policymakers, military leaders, and strategic thinkers worldwide.

Nearly 80 years ago, the German blitzkrieg took Europe by storm. Often lost in discussions about the German military’s panzers and Luftwaffe is that the assault on France would have never succeeded had it not been for “the remarkable performance of the German infantry.” Yes, it was the world’s best infantry small units that set the conditions for the German blitzkrieg in Sedan, France, allowing Germany to capture almost all of Western Europe in a month’s time. When the German Army was stopped at the Meuse River in Sedan, these small units, led by carefully selected and trained sergeants, crossed the water obstacle via small boats and then rapidly destroyed dozens of “pillbox” positions that anchored the French defensive system. The speed in which the Wehrmacht’s close combat “storm-troopers” destroyed these positions enabled their armor forces to cross the Meuse and continue their attack to the English Channel faster than the French could respond.

Fast-forward four years to Operation Overlord, when thousands of American and allied infantry formations crossed this channel with a mission to destroy the German military. At Normandy’s landing beaches and in the bocage, or hedgerows, just beyond them, German infantrymen were dug-in and determined to halt the allied assault. Most War on the Rocks readers are likely familiar from watching Saving Private Ryan with what happened to Alpha Company of the 116th Regimental Combat Team at Omaha Beach’s Dog Green Sector. While certainly tragic, what happened to 39,000 infantrymen in the six weeks after D-Day as they attempted to bust out of the bocage was far worse. The casualty learning curve — measured in blood — for multiple U.S. infantry divisions exceeded 100 percent. Infantrymen lucky enough to survive the brutal, close-in combat learned hard lessons, adapted, and taught thousands of combat replacements better ways to fight, including more effective ways to employ combined arms. These efforts eventually enabled the destruction of the German infantry units in the bocage. Similar to the panzer dash to Dunkirk in 1940, the courageous actions and severe butcher’s bill of U.S. infantry units were what ultimately enabled Patton’s race to Berlin.

The same realities applied to America’s efforts to destroy the Japanese military in the Pacific. In both campaigns, American infantry units suffered 70 percent of the nation’s casualties. And the leaders of these close combat units in places with names such as Guadalcanal, Tarawa, and Iwo Jima learned how to fight the costliest way — through blood. Eventually, the cost of this method of schooling and employing infantry small units grew too high for American strategic decision-makers. After the loss of more than 12,000 killed and 55,000 wounded in the battle for Okinawa, President Harry Truman decided to employ atomic weapons in an effort to finally bring Japan to surrender instead of losing tens of thousands more U.S. infantrymen fighting in Tokyo.

These weapons had their intended effect and World War II ended shortly after they exploded over Nagasaki and Hiroshima. Ever since, nuclear weapons have prevented the outbreak of anything close to the great-power wars that the world experienced in the first half of the 20th century. But they haven’t prevented many other wars, as American infantrymen painfully know better than most. Yet, when it comes to the Pentagon’s manning and training resource prioritization, these same infantrymen have consistently been at the bottom of the priority list. It’s time for this tragic reality to change, not only because the 2018 National Defense Strategy directs increasing “capabilities to enhance close combat lethality in complex terrain,” but also and especially due to adversaries increasingly understanding America’s critical vulnerabilities: aversion to casualties and collateral damage and lack of consistent, focused commitment to conflicts of durations measured in years rather than months or days.

Realities for America’s Infantrymen in a World with Nuclear Weapons

Since 1945, U.S. policymakers have sent the nation’s close combat personnel into battle in every decade, including the past 17 years without interruption. In these conflicts, America’s infantrymen have suffered more than 80 percent of the nation’s casualties. If a War on the Rocks reader comes across a headline on CNN, Twitter, Facebook, or anywhere else stating an American military servicemember was killed or wounded in Iraq, Afghanistan, Syria, or unknown location today, there’s a strong chance that this American was a U.S. Marine, Army, or Special Operations Command infantryman. And within the infantry community, Marine ground-pounders are the most likely to suffer casualties.

Yet, today, only 19 percent of the Marine Corps’ 648 active-duty infantry rifle squads are led by the appropriately trained, sergeant squad leader that they are required to have. No, that wasn’t a typo. Only 19 percent of what are, in theory, the most important units in the Marine Corps are led by someone with the currently required training and experience. But even when that standard is met, it is not enough. Multiple Marine War on the Rocks authors, including an infantry sergeant, have described how current Marine training is insufficient and unrealistic. While the U.S. Army has figured out ways to place more experienced soldiers in charge of their infantry squads, small unit leadership development is insufficient and realistic training deficiencies are also systemic, as highlighted by Maj. Gen. Robert Brown, a recent Maneuver Center for Excellence commander, and John Spencer of West Point’s Modern War Institute. Special Operations Command appears to have figured out how to meet both the small unit leader experience and training requirements. But that command doesn’t have the necessary capacity to meet American policymaker demand on its own.

Most of the costs involved in fixing these problems would be rounding errors in the defense budget. So why do these problems persist? Simply because the simple solutions to fix them are routinely met with resistance. And this resistance comes either from misinformed priorities or inaccurate claims of insufficient funding.

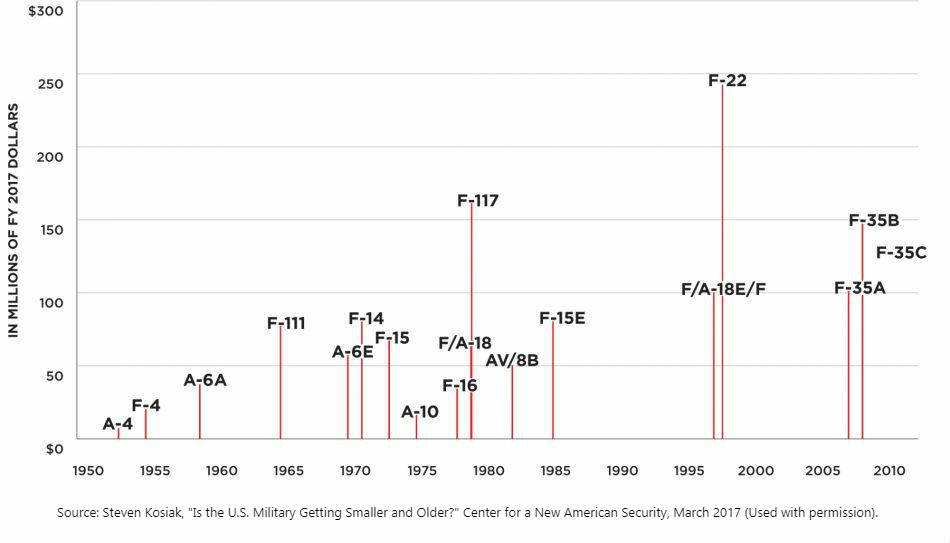

Where is the money going? The annual defense budget is around $600 billion, not including funding for overseas contingency operations. Specific to the Marine Corps, the service is spending anywhere from $130 to $150 million on each F-35B and F-35C, with a plan to buy more than 400 jets. These aircraft cost anywhere from $40,000 to $50,000 per hour to operate and $11 million to train each pilot. Altogether, these costs, as per Steven Kosiak’s recent defense spending analysis illustrated below, are around three times, or approximately $80 to $100 million, more per aircraft than the F/A-18s and AV-8Bs that they’re replacing. Additionally, the pilot’s base salary typically ranges from $5,000 to $7,500 per month, not including $125 to $840 more a month in aviation career incentive pay and annual flight bonuses of up to $20,000. In comparison, an infantry sergeant, if the squad has one, is paid around $2,800 per month and the money invested in his equipment and training is exponentially less.

We don’t share these numbers to suggest that it’s unreasonable for the procurement, operating costs, and training for a jet pilot to be higher than that for infantry units. We understand why this is the case. Rather, we hope to get more people to think through the consequences of replacing the current inventory of short-range tactical aircraft with airframes that cost three times as much. Further, more people should think through the consequences of doing so in a relatively steady, if not decreasing budget environment.

Something’s got to give. And, to date, manning, equipping, and training (and optimally supporting) the nation’s close combat forces has borne the brunt of the cost. Rep. Niki Tsongas, the ranking member of the House Armed Services tactical air and land forces subcommittee, recently highlighted her concerns with this funding imbalance: “While the Marine Corps certainly has a need for aircraft of many types, the ratio of spending on aircraft compared to ground equipment is striking.”

Perhaps even more concerning about the exponential spending disparity is that neither the F-35B nor F-35C can provide air dominance, much less air superiority, for America’s close combat forces. Consider, for example, a combined Army, Marine, and special operations force assault such as what the nation’s joint close combat forces executed in Najaf and Fallujah in 2004. If America’s infantrymen were tasked to execute anything like these operations today, against even more capable adversaries, it’s all but guaranteed that they’d have to deal with enemy armed commercial-off-the-shelf drones, or what the SOCOM commander recently described as his “most daunting problem” in 2016. In such a threat environment, even if two, four, or 20 F-35Bs were on-station to support Americans on the ground, the jets wouldn’t be able to do anything about this type of adversary air threat. Nor would they be able to provide the persistent “Guardian Angel” aviation support routinely requested by infantrymen and recently described as “king” of the battlefield at the conclusion of the nine-month Mosul battle. Instead, America’s close combat leaders would have to figure out on-the-fly how to deal with adversary threats from above, while simultaneously locating, closing with, and destroying thousands of enemy fighters concealed in fortified positions. There’s no reason to believe their casualty rates would be anything less than 80 percent when doing so.

Is this what is best for America?

Ultimately, this is why fixing the described infantry manning problem, as senior Army and Marine leaders have discussed for years now, is central to achieving the goal of U.S. Defense Secretary Jim Mattis’ “Close Combat Study.” We will explain in a future article what’s being done across the board to fix these problems, but now we want to focus on one vital solution: the creation of a world-class, joint close combat leader training center to certify those given the privilege to lead the .02 percent of the American population that serve in U.S. infantry units.

Why a Joint Close Combat Leader Training Center?

To answer this question, let us consider a bit more history. During World War II and the Korean conflict, the “exchange ratio” for American air forces was extremely favorable. The ratio between enemy and friendly killed in air-to-air combat over Europe versus the German Luftwaffe was nine to one and, against Japan, 13 to one. In Korea, against North Korean and Russian pilots, the advantage was also 13 to one. For a time in Vietnam, however, the ratio dropped embarrassingly: In 1967, it approached parity.

The response within the Air Force and Navy was immediate and dramatic. Both services began to restore traditional dominant ratios by creating advanced tactical fighter schools, made famous by Tom Cruise: Top Gun for the Navy and Red Flag for the Air Force. These services’ air components, joined in 1978 by the Marine Corps’ aviation combat element’s MAWTS-1, quickly developed new tactics for air-to-air combat. The shock and embarrassment of this tough era also led to the development of a new series of aircraft, such as the F-15, F-16, and F-18. Since Vietnam, these aircraft, in the hands of American and Israeli pilots, have achieved incredible exchange ratios, well over 200 to one.

The results speak for themselves and are, in many ways, common sense: If you give exceptional equipment to carefully selected pilots and thoroughly train them at the individual and unit levels, they then dominate in combat and make their entire units more successful. Beyond this, the services also developed a force generation and manpower model for pilots to absorb and sustain this lengthy, but critical training. They also created rank heavy and large advocacy organizations in the Pentagon to constantly battle for more funding. Tragically though, this has been and remains routinely the exact opposite method used in selecting, equipping, and training the majority of America’s close combat units and their leaders. It’s not hard to understand why the United States invests so heavily in its air components. But it is becoming clearer by the day that it is morally and strategically unacceptable to spend so little on American infantry forces, particularly when Marine infantrymen died at a ratio of near 1 to 1 parity when fighting inside buildings in Fallujah in 2004. There are many things that need to change, but at the top of the list should be the creation of a close combat leader’s equivalent of Top Gun, Red Flag or now the Air Force’s six-month Weapons School, or MAWTS-1’s Weapons-Tactics Instructor Course. This will help ensure, as per the chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff intent, that America never again “send(s) our men and women into a fair fight.”

Time for a Joint Close Combat Leader Training Center

This center’s primary mission should be to certify America’s joint close combat leaders. This should be done by providing annually three 14-week long certification courses. This is slightly longer than Top Gun and almost half the length of the Air Force’s Weapons School. To ensure sufficient capacity for all of the services and key allied infantry leaders, each course should have space for 450 students, who, upon graduation, return to lead their pre-assigned units for a period of no less than two years. The center’s secondary mission should be to lead joint close combat experimentation efforts. These experimentation efforts can occur during the close combat leader certification courses and in the time periods between classes.

The center’s commanding general should be a follow-on assignment for the commander of Joint Special Operations Command (JSOC). Bringing this level of experience and expertise to the mission is increasingly critical as the U.S. defense secretary continues to emphasize the need for Marine and Army close combat units to perform missions that have typically been thought of as falling in the domain of special operations. The general’s instructor cadre should comprise the most capable and successful non-commissioned and staff non-commissioned officer close combat leaders from across JSOC, SOCOM, the Marine Corps, the Army, and America’s closest allies’ military forces. An elite cadre of civilian personnel should support the commanding general by operating the command’s combat conditioning and health center, as well as the immersion simulation, additive manufacturing, and experimentation laboratory facilities.

Fort Bliss in Texas would be an optimal location for enabling close combat leaders to gain maximum proficiency in employing live ordnance, including from long-range, joint firing platforms. Fort Bliss also enables close combat leaders to train with the variety of information warfare capabilities that can support their units. Equally important, Fort Bliss is home to the Army’s world-class Sergeants Major Academy. The joint force’s top enlisted leaders attend the Sergeants Major Academy. These senior enlisted leaders can provide countless benefits in the development of the nation’s future close combat leadership.

The center’s core complex should include a world-class training facility comprising a combat conditioning and health facility similar to elite collegiate Division I sports’ programs. It should also have an enhanced and expanded, multiple hundred-thousand square foot infantry immersion simulation laboratory. This simulation facility should take the Camp Pendleton “tomato factory” and tactical decision kit models to an entirely new level: Think “tomato factory on steroids.” Additionally, the center should have combined arms urban and subterranean facilities similar to Marine Corps Base 29 Palms’ Range 230 and Range 220, as well as an artificially created jungle warfare training area. The complex should also include an additive manufacturing shop modeled on those recently used by ISIL, although projected forward to what a group like this will have in ten years. This shop should be part of the command’s joint close combat force experimentation laboratory. And the headquarters should have a subordinate command located at the Mountain Warfare Training Center in Bridgeport, California, where each class will conduct three weeks of mountain and cold weather training.

The course design should consist of the following five phases:

Phase I: Core Foundation (four weeks in length and then integrated throughout the course, with a train-the-trainer approach)

Phase II: Urban Combat Foundation (three weeks, with JSOC operator mentors)

Phase III: Thick Vegetation and Jungle Combat Foundation (three weeks in length, with JSOC operator mentors)

Phase IV: Mountain and/or Cold Weather Combat Foundation (three weeks in length, Bridgeport, California, with JSOC operator mentors)

Phase V: Certification Week and Graduation Ceremony (one week in length, with JSOC operator mentors)

Establishing a joint close combat leader training center with the proposed leadership and instructor cadre, who have access to world-class facilities on par with those that exist for collegiate athletes and the services’ aviation components at Fallon Naval Air Station, Nellis Air Force Base, and Marine Corps Air Station Yuma, is a long overdue and vital step. This step will ensure that Gen. Dunford’s intent to never again send America’s close combat units into a fair fight is met. Additionally, in one of, if not the most rapidly changing and complex security environment the U.S. military has ever encountered, this step will ensure America’s close combat units can constantly learn, adapt, and share the best tactics, techniques, and procedures to gain maximum advantage against all potential adversaries.

The Moral and Strategic Imperative for the .02 Percent

Close your eyes and picture a jam-packed NFL stadium filled with individuals excited to watch the Super Bowl. Now picture the stadium seats filled by Army, Marine, and SOCOM close combat personnel. This is the .02 percent of the U.S. population that we’ve focused on in this article. That’s right, out of a population of nearly 330 million, the combined total of all American close combat personnel, from all services, can fit inside any NFL stadium. These are the American warriors whose predecessors have taken more than 80 percent of the nation’s casualties since World War II and who will continue to suffer the lion’s share of U.S. combat losses — while consistently receiving only a miniscule percentage of defense funding. That is, unless action is taken now. It’s long past time to right this wrong. America’s future security depends on it.

Retired Major General Bob Scales is a former Commandant of the Army War College, an artilleryman and author of the book Scales on War: The Future of America’s Military at Risk, published by the Naval Institute Press.

Scott Cuomo is a Marine Infantry Officer and MAGTF Planner currently participating in the Commandant of the Marine Corps Strategist Program at Georgetown University.

Jeff Cummings is a Marine Infantry Officer and currently serves as a Military Faculty Advisor at The Expeditionary Warfare School, Marine Corps University.

The opinions here are those of the authors and do not represent the positions or views of the U.S. Army, U.S. Marine Corps, the Department of Defense, or any organization therein.