Gauging the German Reaction to America’s New Direction

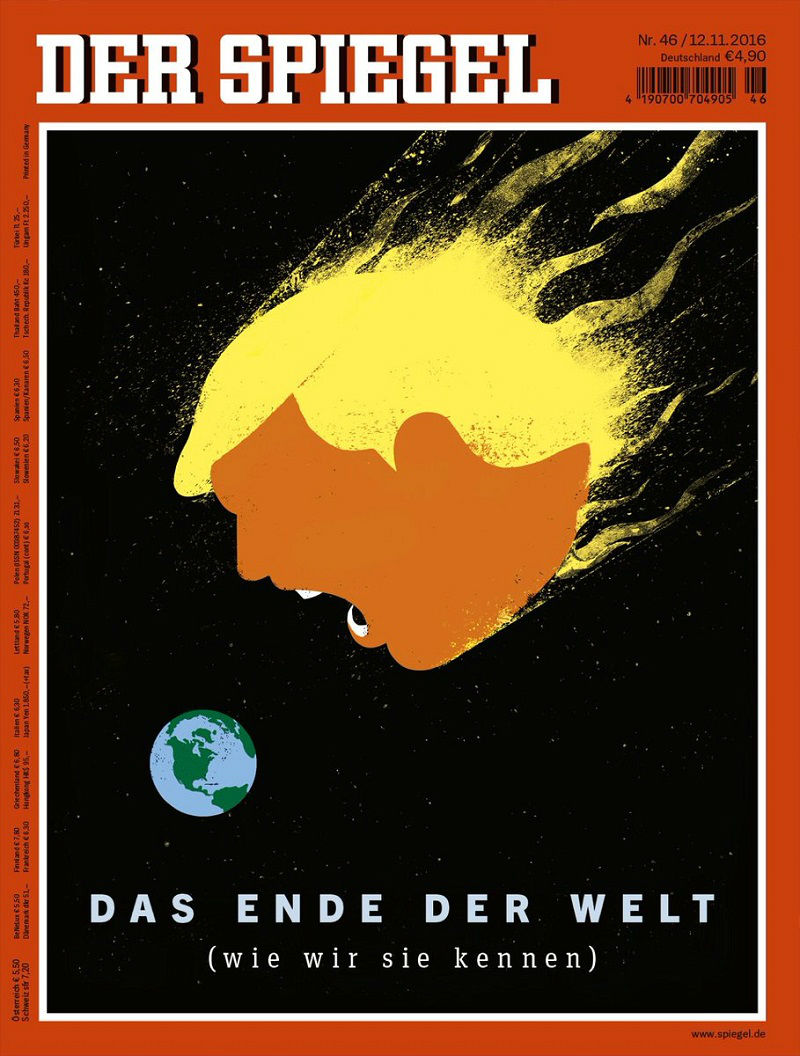

When I landed in Germany last week the cover of the weekly the news magazine Die Stern pictured a frowning President-elect Donald Trump and warned, “The Unholy President: Why the World Must Be Afraid.” The Focus weekly had another frowning Trump hovering over the headline, “The Rage Coming to the White House.” The cover of the more sober weekly Der Spiegel showed Trump hurtling like a meteor toward Earth saying, “The End of the World as We Know It.” Thoughtful German observers were moving past the hysteria of the headlines, however. As I visited German universities and think tanks on speaking tour in Kiel, Hamburg, Nuremburg, Freiburg, Munich, and Heidelburg, analysts were looking past the initial shock of the Trump election victory and beginning to ponder what Trump may do and how Germany might react.

Broadly speaking, these analyst don’t know what Trump’s foreign policy will be, and I’ve gotten similar questions about Trump and Putin everywhere I went. The president-elect’s campaign message that NATO countries should do more for the common defense has been received loud and clear among the policy wonks. Facing the Baltic Sea, Florian Watzel, a research associate at the Institute for Security Policy in Kiel (ISPK), told me that Russia’s foreign policy seems to have the negative aim of upsetting existing structures to weaken other states in Europe instead of building new avenues toward stability. Germany will not be able to stand still if Trump reduces America’s role in Europe, he opined. Christian Patz, another analyst at the ISPK, agreed with the threat assessment and said that Germany can do more for the common European defense, given its balanced budget. He and other analysts opined that Germany will likely redouble efforts to establish common European military units. Patz highlighted the integration of a small Dutch unit in a larger German rapid-reaction force. ISPK defense analyst Sebastian Bruns noted that German navy ships already call on Baltic state ports and observed that NATO is rotating ground units into Baltic states as well. In southwestern Germany, professors from Freiburg University and journalist Annemarie Rosch of the Freiburg newspaper Badische Zeitung noted that stability in Poland and the Baltics is hugely important to Germany. All these observers also highlighted that the new right-wing government in Poland makes a larger German role aimed at reinforcing stability in the East trickier. Bilateral relations with Poland, while nowhere near a crisis, are less friendly now. Rosch, like Watzel, commented that the possibility of new right-wing governments in European capitals such as Paris could impede any German effort to boost Europe-wide steps to bolster common defense. There was broad consensus that the German public would support more defense efforts if the German government explains the rationale for such a course in response to a diminished American role under Trump.

Beyond the questions about U.S. foreign policy, Trump’s victory has led many Germans to wonder about the direction of the United States. I didn’t hear agreement with the anti-globalization sentiment expressed by many Trump supporters. The German export machine, my interlocutors believe, is functioning well. However, in a country that greatly values social welfare, I did hear sympathy for the difficulties many American communities have with economic dislocation. I’ve heard worry about a Trump administration’s stance on climate change. There is also alarm at the more extreme elements of the Trump support base. Andreas Falke, a longtime American Studies professor at Nuremburg University, observed that many Germans used to agree with the vision of the American “shining city on a hill,” famously championed by Ronald Reagan as the Cold War entered its last phase. That vision had suffered with the unilateralist policies of George W. Bush, but recovered under Barack Obama. Falke revealed that he urged his students not too be too hasty in judging where American society is headed, but then came under intense criticism for acting as an apologist for racism and sexism in the eyes of some of students. It will be a huge challenge, Falke concluded, for American diplomacy to rebuild the image of the United States among German young people. Trump seems to have significantly damaged the American brand even before taking office. Falke hopes that the new administration will think carefully about the outreach skills of its foreign policy team and its new ambassador in Berlin. He noted that this ambassador still commands wide attention in the German media and wondered if it would be too much to ask for the new ambassador to speak some German to boost that very necessary outreach.

I don’t have much professional experience working with Germany or with Europeans more generally. I was there to talk to experts and more general audiences about the threat of extremism in the Middle East. I am struck, however, by the concern about the new American president even in a country as friendly to the United States as Germany. The essential question is whether the United States is going to relinquish its role as world leader in favor of a sharply limited foreign policy. (I heard similar questions from Saudis and Emiratis in the Persian Gulf last week.) In Germany, I heard questions about whether America is still firmly attached at home and abroad to the values that separate the West from governments such as Russia. There is time to reassure friends around the world, and the United States possesses very capable professional diplomatic and military personnel to help the new administration team do that. Before we can do that, however, the new administration needs to define whether it actually wants to maintain America’s leading role, what it wants from allies, and how firmly attached it truly is to the values of the international order that the United States created after the cataclysm of World War II.

Robert Ford was the American ambassador in Algeria, 2006-2008, deputy ambassador in Iraq 2009-2010 and ambassador to Syria 2011-2014. He is now a fellow at the Middle East Institute in Washington, DC and teaches at Yale University where he is a fellow at the Jackson Institute.