Join War on the Rocks and gain access to content trusted by policymakers, military leaders, and strategic thinkers worldwide.

Close air support (CAS) is air action by fixed-wing and rotary-wing aircraft against hostile targets that are in close proximity to friendly forces and requires detailed integration of each air mission with the fire and movement of those forces.

Department of Defense Joint Publication 3-09.3

The (eventual) retirement of the A-10 Warthog has been a challenging issue for the Air Force. The original plan to replace the A-10 entirely with F-35 has fallen by the wayside, buttressed by the reality that the extended combat deployments undergone by the fighter/attack force were never envisioned when the F-35 plan was hatched. Twenty-five years of continuous conflict, most of it irregular in nature, has highlighted the utility of a relatively slow, heavily armed multirole aircraft. Our operations over the past decades have been largely very similar to the kind of counterinsurgency demands that led to the requirement for a new attack aircraft (then called A-X) in 1966.

As the Air Force has moved toward the position that a replacement attack aircraft (A-X2 or OA-X) is necessary, one persistent issue continues to arise: What kind of aircraft might be able to do “high threat” CAS? In a presumed environment where the air defenses are too lethal for the A-10 to survive, wouldn’t the F-35 be a better alternative? The question itself is highlights a persistent trend in Air Force concept development — a mythical set of conditions that is highly unlikely, fundamentally not credible, based on a misunderstanding of the air threat, or, in this case, all three. There is no reasonable case to be made for an aircraft that can survive in a high-threat CAS environment, because there is no credible case to be made that any aircraft can survive in such an environment. It isn’t that there isn’t a need to apply airpower in such an environment. Rather, it is that having a need doesn’t equate with delivering a capability. The idea that the Air Force can deliver effective CAS in a highly contested environment is a myth, one that the Air Force would be well served to get rid of.

A Challenging Environment

A high-threat CAS environment involves a situation that is unprecedented in Air Force history. In this scenario, U.S. ground forces are in need of aerial fire support while under an adversary air defense umbrella. The air defenses are so severe that legacy aluminum jets are useless. Only stealthy aircraft or standoff munitions can save the day for the beleaguered infantry. Into this scenario are shoved several potential concepts, including the F-35 in a CAS role, the “weapons-centric CAS” concept, and the ubiquitous use of standoff weapons to provide responsive fires from great distance. Aside from the fact that this kind of fire support is best provided by long-range artillery, the idea that CAS can be conducted in such an environment fails on two fronts: it is extremely unlikely that we will have ground forces in this condition, and the postulated environment is too lethal for even stealth aircraft.

For more than a decade, the idea that “capabilities-based” threat analysis could provide a valid input to defense planning has held sway. In the absence of a defined strategy, a planner could simply match adversaries somewhere in the world with capabilities, also available somewhere, to create a new threat against which the defense strategy could be developed. A lazy approach to strategic planning, it allows for the ludicrous matching of “one from column A and one from column B” adversaries and capabilities. Reality is more constrained. Only Russia and China have the force structure and design that pose a substantial threat of this nature. Iran’s air defenses have not largely embraced a mobility doctrine, and if North Korea ever goes on the offense, their radar SAMs will be left where they are.

With that grounding in reality, the follow-on question remains: Under what conditions might we see a demand for CAS? With respect to China, the answer is easy. We won’t. There are no U.S. ground forces stationed in positions where they are in danger of being overrun by the People’s Liberation Army. We’re not going to ever stage an amphibious landing on the Chinese mainland, and if we did, no amount of CAS is going to save those Marines from rapid annihilation. The idea that we could push a landing force through an air defense environment is ludicrous on its face, and it’s never been done. Any expectation that China would replay the Korean War and join a North Korean attack on the south is similarly unlikely. If we face a high-threat CAS environment, it won’t be against China.

Russia’s resurgence offers a slim reed to grasp for the purveyors of the high threat scenario. It might be possible for the Russians to overrun one of the U.S. Army brigade combat teams permanently stationed in the Baltics. Except that there aren’t any. U.S. Army Europe is so depleted that it lists two stateside divisions on its homepage. This is justified by the idea that the 3rd and “4th Infantry Division is a regionally allocated force, or CONUS-based force that falls under operational control of USAREUR when deployed to the European theater.” Unfortunately, the 3rd ID (Georgia) and the 4th ID (Colorado) aren’t likely to arrive in time to save the day. The ground combat power in Europe is limited to the 2nd Cavalry Regiment in Germany and the 173rd Airborne Brigade in Italy. That’s one regiment and one brigade, neither of which has a land route to the Baltic states. And let’s face it: Any environment bad enough to prevent aluminum jets from providing CAS isn’t going to allow airlift aircraft through to drop airborne infantry or allow passage of sealift packed to the gunwales with Stryker armored vehicles.

The logical convolutions required to place U.S. forces in a position where CAS is required in a high threat environment are a stretch. They require the presence of forward-deployed combat forces in danger of being attacked by Russia or China upon short notice or the existence of a joint forcible entry into the teeth of advanced defenses. Neither condition is credible.

The Evolution of Divisional Air Defense

The Air Force has never done anything that looks like high-threat CAS in a modern environment. Arguably, it has never done CAS inside an intact air defense environment. Certainly there have been threats to CAS aircraft. It is a dangerous mission that often involves loitering over enemy ground forces. The largest modern dataset was provided in Operation Desert Storm, where Iraqi Army and Republican Guard formations lost their strategic SAM coverage and most of their few radar systems but continued to pose a threat with IR missiles and anti-aircraft artillery (AAA).

When the A-10 was designed, the primary AAA threat posed by a Soviet motor rifle division was the 14.5 mm heavy machine gun, which was visually aimed. The 23mm threat was present in small numbers. Each division had four 4-vehicle platoons of the ZSU-23-4 Shilka antiaircraft tank, which had its own fire control radar meshed with four 23mm automatic cannon. Small numbers of visually-aimed 57mm cannon were also expected, along with SA-7 and SA-9 heat-seeking surface-to-air missiles (SAMs). SA-6 radar SAMs entered production in 1967, before the A-X concept was formalized. As has been amply demonstrated in combat, this combination of weapons can and does bring down aircraft, although the A-10 proved remarkably resilient.

But Soviet designers were unimpressed by their own 23mm cannon and by the Gainful missiles of the SA-6. Even before Egyptian Shilka and SA-6 Kub systems devastated low-flying Israeli jets over the Sinai in 1973, the Soviets were moving towards heavier guns and more lethal SAMs. The 23mm round was largely abandoned in favor of the 30mm cannon, and the Tunguska was delivered to the Red Army while the A-10 was still in its production run. The Tunguska was everything the Shilka wanted to grow up to be — it had four 30mm cannon, an acquisition radar to go with the HOT SHOT fire control radar, and four (soon to be eight) SA-19 radar missiles on the sides of the turret. The optical sighting system incorporated a thermal camera. A Tunguska gunner was spoiled for choice when it came to weapons selection, and it was blessed with a round that weighed twice that of the 23mm cannon with half again the muzzle velocity.

Similarly, the SA-11 Buk was a substantial improvement on the SA-6, adding more missiles with better capabilities and quadrupling the number of target tracking radars in the battery. It had longer range, fancier radars, a quicker reload, and an optical night capability that the SA-6 lacked. It entered service when the A-10 was halfway through its production run.

The air defense threat posed by the Chinese and Russians only got worse after Desert Storm in 1991. Russian and Chinese designers saw the effect of precision weapons and elected to try and intercept those too. The Russian SA-15 Tor and the SA-22 Pantsyr advertised anti-munition capability. The Chinese played another trick by taking naval gun systems designed to defend ships and placing them on trucks. To add insult to injury, the LD-2000 system is a radar-controlled, seven-barreled Gatling gun derived from the Dutch Goalkeeper — which uses the very came GAU-8A cannon embedded in the A-10. A cannon designed to bust medium tanks (from the side, anyway) makes a dandy antiaircraft weapon, and with good fire control it is absolutely capable of engaging munitions. These system examples are not isolated — at least in Russia and China, counter-munition capabilities have become ubiquitous among the air defense units assigned to protect moving ground forces.

Faulty Concepts

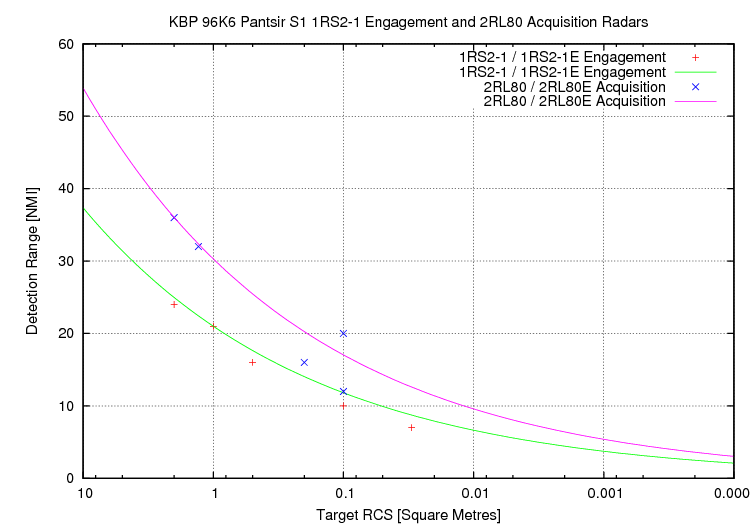

Modern high-threat CAS concepts promulgated within the Air Force largely miss the goal because they conceptualize an air defense environment that departs from reality. If aluminum jets can’t get to the target, neither can aluminum and steel weapons. Even America’s vaunted stealth capabilities do it absolutely no good at gun range. The detection range curve for the SA-22 in Figure 1 demonstrates diminishing returns — even reducing the radar cross section to the target to a spectacular one ten thousandth of a square meter (one tenth of a blue-winged locust) still allows the SA-22 radar to track at gun ranges.

Figure 1: Estimated Detection range Curves for the SA-22 (Dr. Carlo Kopp)

The radar stealth issue is itself a red herring. One U.S. Air Force officer recently claimed that the F-35 would perform CAS using methods that allow it to loiter around the battlefield at medium altitude locating and targeting SAMs “without the threat knowing I’m there”, essentially claiming that he could mix suppression of enemy air defenses (SEAD) and CAS together in an invisible single-seat airplane loitering in hostile airspace. This in a dark-colored, medium-sized aircraft that has an exhaust hot enough to melt steel decks, and only against SAM operators stupid enough to turn on their radars before they have a target. SAMs and radar-guided AAA almost always get to attack from ambush, and they can be cued by other radars, optical or heat sensors, or individuals with ears and a pair of Mk 1 eyeballs. Not all systems are radar-guided and some can only be located by the missile exhaust or muzzle flash — by which time they have already fired.

In Desert Storm, the radar threat was effectively neutered within 72 hours, leaving guns and heat-seeking SAMs functional (they are effectively impossible to suppress) and capable of hitting aircraft. The vast majority of aircraft hit in Desert Storm were hit in the target area, with most hits being on aircraft loitering over Iraqi ground troops (A-10, OV-10, AV-8 and F-18).

Figure 2: Aircraft lost and damaged by phase of flight, Gulf War

Aircraft that typically loitered looking for targets were treated as being “in the target” area — this covered all Battlefield Air Interdiction (BAI), CAS and Forward Air Control (FAC) taskings, plus interdiction tasked A-10, AV-8B and Marine F/A-18. Hidden in this data is the fact that most aircraft that were successfully targeted were exposed to hits because they made repeated attacks in a target area or loitered in the threat area near ground troops. This is the reality of the CAS mission — loitering in the vicinity of troops protected by ground-based air defenses.

Expanding the data set to include all NATO fixed-wing combat aircraft for all conflicts since the Falklands reveals that even a benign CAS environment isn’t benign. CAS and BAI sorties count for more aircraft hit than interdiction sorties, even though interdiction sorties are vastly more common.

Figure 3: Loss and damage by mission, all NATO nations, 1982-1999.

Put simply, aircraft which loiter over dense concentrations of air defense systems are going to get hit. Air defenses are more lethal than ever before. Therefore, an aircraft performing traditional CAS in an evolved air defense environment is likely to get hit. At a minimum, this means that it flies home, but against a modern threat, it more likely means that the aircrew walks home. Russian and Chinese tactical air defenses are entirely capable of hitting loitering targets and their munitions, and targets that get hit will not be able to shrug off the damage.

Wrapup

In certain environments, CAS is not a practical option, be it in a traditional fashion or within a tactically questionable concept where weapons are lofted in from outside. Even stealthy aircraft, as they currently exist, are not designed for this environment and are at a serious disadvantage against short-range air defenses even if the longer-range SAMs and interceptors are neutralized or suppressed. This condition presages the conditions that are likely to prevail if directed energy weapons take the field in numbers and where merely flying within view of an air defense energy weapon may be impossible.

Accepting that some missions are effectively impossible is an acceptable outcome, because the conditions under which high-threat CAS might be required are unlikely. This is one of those cases where even an unabashed airpower advocate like myself may have to admit that there are cases where airpower is not only not the best option, but may not be a practical option at all. The high-threat environment may, in fact, be the best argument for land or sea-based precision artillery, which flies faster, can be massed more effectively, is less subject to intercept, and is substantially cheaper than any conventional, air-delivered option. It is absolutely unnecessary for the Air Force to pursue an expensive, technologically challenging, tactically unexecutable, and strategically infeasible capability that unnecessarily duplicates artillery capabilities resident in the other services. If the Army or Marine Corps believe that they need fire support in an environment where even air-launched weapons are likely to be intercepted, then they should be encouraged to invest in their artillery capabilities. For the Air Force, making an argument that airpower can be effective in performing high threat CAS is not a credible story and could drive an unnecessary and unproductive diversion of scarce resources. There are other problems to solve with airpower.

Col. Mike “Starbaby” Pietrucha was an instructor electronic warfare officer in the F-4G Wild Weasel and the F-15E Strike Eagle, amassing 156 combat missions and taking part in 2.5 SAM kills over 10 combat deployments. As an irregular warfare operations officer, Colonel Pietrucha has two additional combat deployments in the company of US Army infantry, combat engineer, and military police units in Iraq and Afghanistan. The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Department of the Air Force or the U.S. government.

Image: U.S. Air Force photo, Master Sgt. Lance Cheung