Join War on the Rocks and gain access to content trusted by policymakers, military leaders, and strategic thinkers worldwide.

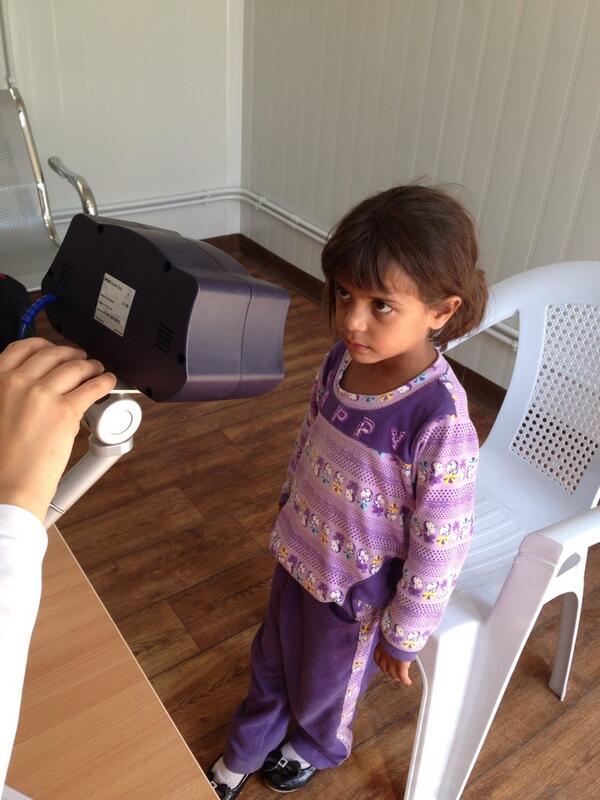

Samira stands looking diligently at the camera. At six years old, she is being enrolled in the first countrywide implementation of biometrics by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. Samira caught my eye because she is not a MAM — a military aged male — like the hundreds of Iraqis and Afghans I helped enroll in the U.S. military’s biometric efforts in those countries after 9/11.

Samira. Photo credit: Andrew Harper, UNHCR

Biometrics are measurable human signatures that include a heartbeat, the shape of your ear, the way you walk. But when it comes to security measures, biometrics like fingerprints or iris recognition are more heavily used because of their uniqueness. It’s easier to distinguish someone by an iris — the colored part of the eye — rather than, say, data from the person’s Fitbit. By 2005, the U.S. military was using biometrics in Operation Iraqi Freedom and later employed them in Operation Enduring Freedom in Afghanistan to help ensure those given access to U.S. military installations weren’t known criminals or bomb-makers, and to help isolate known insurgents from the local populace.

The challenges to those using biometrics for refugee relief and management are far different than those faced by the U.S. military, although the United Nations has built up substantial expertise since it started registering Afghan refugees in 2002. What makes biometrics so compelling for use in refugee crises is its ability to give individuals who have nothing something powerful — a proof of identity even without a government-issued credential like an identification card or passport. Biometrics can dramatically decrease the amount of fraud in the distribution of aid, save refugees from long wait times to receive benefits, and reduce the possibility of radicalization of vulnerable refugee populations. As a biometrics engineer, I have three main questions regarding governance of the United Nations’ use of biometrics with refugees.

Who deserves a peek at the United Nations biometrics database?

In Iraq and Afghanistan, the U.S. Department of Defense compiled a biometrics database of registrants who sought employment on U.S. military bases as well as those who were suspected of acts of terrorism. As of now, the U.N. database has been set up to house registrants who display an entirely humanitarian need — those fleeing states of war who need temporary support while their lives are disrupted.

One challenge posed by the United Nations advancement of biometrics: How long before registration information is used in a court of law? Enrollment devices are currently mounted in banks and enrollment stations, but the ability to have a mobile device available is not far off and would allow the United Nations to conduct policing patrols with biometrics. Another question regards whether a nation state should have access to a refugee’s U.N. biometrics record to ensure that the individual seeking asylum has interacted with the United Nations and can prove reliance and inability to subsist in such circumstances.

If NATO suspects a known bad actor is seeking safe passage under the U.N. banner, does it have the right to use U.N. biometric information to confirm its suspicions? Does the information of Syrian refugees in Jordan get stored alongside U.N. biometrics enrollment data from refugees in Malawi and Sudan? Should refugee information be stored in the same database as U.N. biometric enrollment data of fishermen in the Gulf of Aden? Mixing data users, data origination, and data types increases points of vulnerability in the system.

Some privacy mechanisms have been built in. The system set up in Jordan is restricted to iris recognition only. Unlike fingerprints, irises can’t be left behind at a crime scene so an iris database is less likely to be important in a prosecution. But other common measures to limit the amount of data held such as disposing of it after a certain amount of time seem less likely in this situation. The database is helpful in tracking refugee flow between camps and in highlighting cases of special needs, so it is hard to imagine a scenario where a data dump policy would take hold.

Who owns the data?

In the case of Syrian refugees in Jordan, does the information belong to Jordan since the data was collected in Jordan? Or does it belong to the individual, since it is the person’s eye and biographic history that makes up the record? Or does the information belong to the country where the database is stored, which — as a safeguard — is often not the same country where the information is being collected? Does the data belong to the government of Syria? Is it safe to return information to a country with a known history of reprisal against opposition? Or does the information belong to those countries where the refugees may eventually seek asylum?

In both Iraq and Afghanistan, the United States attempted to use biometrics as a peace offering — setting up pathways to return stripped-down biometric files to the Iraqi and Afghan governments. But is that too risky in certain refugee situations? Could some make an argument that Assad is the rightful owner of biometric records of Syrians now in Jordan, Iraq, Turkey and Lebanon?

Just as intelligence analysts would likely want to comb through the data to pinpoint any foreign fighters traveling through refugee camps, some governments may also want to use the data to target dissidents. The potential for function creep — when a technology designed for one purpose is used for another — is apparent as solicitations for the U.N.’s biometrics information increase. There are already partnerships between the U.N. biometric database and local banks, just as there are “regular data exchange mechanisms” between the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees and the Public Security Department of Jordan, The Jordan Times reported.

What is the future of the U.N. biometrics database?

The Secure Identity & Biometrics Association recommends that the U.S. government extend biometrics tools to help track Syrian refugees in other countries using the Department of Defense Foreign Military Sales program. IrisGuard, the company behind the most widely used biometric device in Jordan, has announced plans to expand to Europe, while U.K.-based company Simprints is emerging in the field of mobile biometric devices for development.

Just as the U.N. was initiating its biometric practices in 2013 in Jordan, researchers Alan Gelb and Julia Clark at the Center for Global Development were publishing their findings regarding 160 cases where biometrics has been used in developing countries for economic, political and social purposes. Their work shows that the use of biometrics in humanitarian cases is not new, but that the U.N. has entered the global identification market in a much stronger position to negotiate for data exchanges — a database of over 1.5 million individuals.

By U.N. High Commissioner for Refugees estimates, protracted refugee situations typically last 17 years. How old will Samira be before she no longer needs to be in the U.N. database? Will she look back on the system as empowering? Will biometrics become what the Center for Global Development envisions, similar to microcredit and mobile phones “in the far-reaching ability to transform poor people’s lives?” An earlier era had its “Afghan Girl,” the name given to a haunting portrait on the cover of National Geographic that humanized female refugees in 1985. Will Samira be the digital age’s Afghan Girl, a picture of a life in turmoil that will be painted through biometrics?

Sarah Soliman led U.S. Special Operations Command’s first Identity Operations team in Afghanistan, as chronicled in the book “All the Ways We Kill and Die.” She is an Emerging Technology Trends Project Associate at the nonprofit, nonpartisan RAND Corporation and is pursuing her doctorate through King’s College London’s Department of War Studies. She can be reached @BiometricsNerd.

Photo credit: UK Department for International Development