The Ghosts of Soviets Past: Two Army Intelligence Officers Explore an Abandoned Cold War Military City in Latvia

Editor’s note: In December 2015, two Army intelligence officers set out on a trip to explore the mysterious remnants of the Soviet Union in the Baltic States. This article is the first in a series detailing their journey.

A few hundred miles southwest of the Latvian capital of Riga, near the Lithuanian border, lies the town of Skrunda, a bucolic municipality not unlike hundreds of other small towns and villages in the Latvian countryside. But several miles outside of the town center stands the inconspicuously named Skrunda-1, a ghost town that was once a closed city home to 5,000 Soviet soldiers, technicians, and their families.

During the Cold War, the Soviet Union established numerous secret settlements to support sensitive military bases and research sites. Collectively, these sites were known as “closed administrative territorial entities” (or ZATO, their Russian acronym). These classified population centers, numbering well over one hundred, were filled with an imported Russian workforce. They were fenced off from the rest of the general population, heavily guarded, and often removed from official maps and documents. These secretive locations were given a simple postal code designation, typically using the name of the nearest “open” municipality and a number. Early on, the number was used to denote the distance of the closed city from an unclassified location (Arzamas-60, the birthplace of the Soviet atomic bomb, was 60km from the city of Arzamas). However, it was later deemed that the geographical distance was too sensitive to divulge, so many of the numbers were simply arbitrary. These closed cities were designed to be self-sufficient, with their own utilities, entertainment, schools, and hospitals. Skrunda-1, despite being a relatively small example, was no exception.

The advent of medium-range ballistic missiles by the United States and the Soviet Union prompted the latter to develop an umbrella of early warning and detecting capabilities. A Dnepr phased array radar (NATO designation: Hen House) was set up near Skrunda in 1963, but it was not until the 1980s that the closed city of Skrunda-1 was built to support construction and staffing of a modernized Daryal radar system (NATO designation: Pechora). The Soviet Union collapsed before the system was operational, but Russian forces remained at Skrunda-1 until 1998, and a radar system in Belarus was completed to replace the Dnepr system.

Finding Skrunda-1 is no easy task. The abandoned town is slowly being consumed by nature and remains shrouded by dense pine forest common throughout Latvia. However, with geospatial intelligence courtesy of Google Maps, a GPS system, and the discovery of an urban exploration site maintained by some enterprising Latvian teenagers, we were able to pre-plan our avenue of approach and find it with relative ease.

As the pine forests yield to an open clearing, Skrunda-1’s block apartments and water tower came into view, towering over the flat Latvian countryside. The bumpy dirt road we traversed suddenly became a pre-cast slab concrete road, a signature of most Soviet bases and complexes and a good indicator that we were approaching our intended destination. The concrete road’s bare grey surface contrasted with the greenery of surrounding overgrowth, making the roads easily identifiable using satellite imagery (aka Google Earth).

We began our journey on foot, passing through a ramshackle gatehouse into the industrial area of the town, which contained a derelict substation, vehicle repair garages, a boiler plant, and the skeletal remains of a factory. Scavengers have carted off most of the metal, but old technical manuals and inventory checklists remain scattered across the floors of shops and warehouses. In one building, crates of workers’ drab coveralls sat unopened, complete with rusted hammer and sickle buttons.

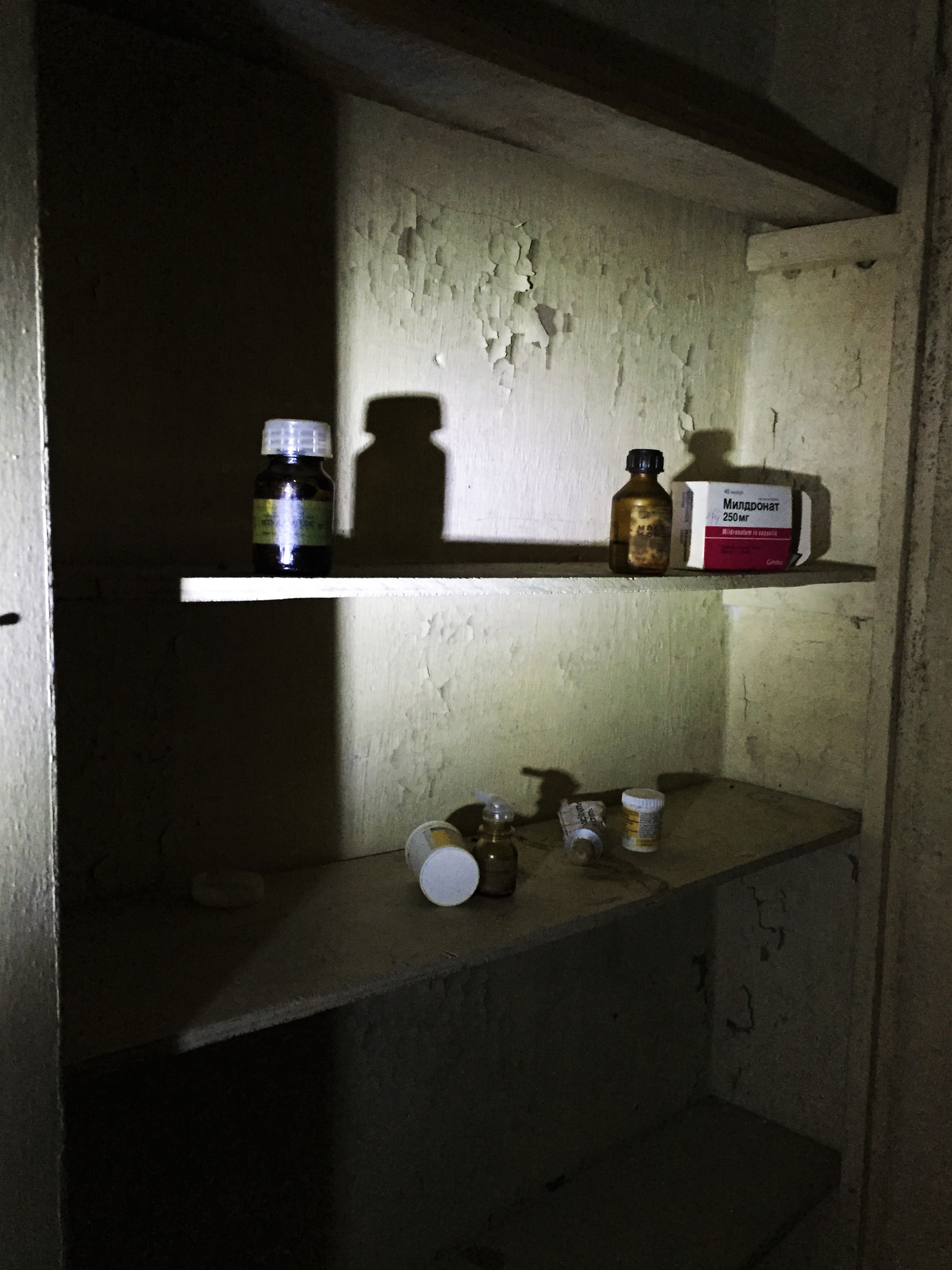

Within the orderly rows of brutalist walk-up apartments that once housed Soviet soldiers, workers, and their families, one can still find remains of a bygone era. Medicine cabinets still contain drugs; bedrooms still have faded posters of teenage idols.

The town’s gymnasium has militaristic calisthenics and martial arts instructional posters still adorning the walls, as well as murals commemorating martial and athletic prowess.

A large message on the wall of the basketball court reads, “Victory Starts Here.”

As we ventured through the primary school, we paused in astonishment at the dystopian nature of a pastel-colored handrail leading up to the second floor. The walls of the stairwell contained glass mosaics of children playing instruments surrounded by colorful animals under a smiling, beaming sun. Upstairs, dozens of brightly painted wood cubbies lay empty as they sank into the moldy floor. Walking through Skrunda-1, adventurous explorers are greeted with post-apocalyptic scenes such as these behind every door.

The sky flared brightly from a brilliant orange sunset, until the sun quickly retreated below the pine-edged horizon, and darkness engulfed the countryside. Winter days are not long in the Baltics, and we had no plans to be Skrunda-1’s overnight guests. Walking back towards the gatehouse along the barren concrete slab road lined with derelict apartment buildings, a white spire caught our eyes. We approached the memorial obelisk down a short path. Nowadays, there is little left of the memorial besides the obelisk, though it is not hard to picture it on a sunny Victory Day in the 1980s, its base bedecked with floral wreaths and honor guards posted at its four corners. Skrunda-1’s citizens fade into view in front of the memorial, lining the main road and admiring a parade of Soviet soldiers passing by. We continued our trek back to our car as the sounds of stomping boot steps and martial music echoed into eternity.

The future of Skrunda-1 remains uncertain. The Dnepr and Daryal radar sites were demolished over a decade ago, and the town continues to crumble into obscurity. The complex was purchased at auction in 2010 by a Russian investor, but whatever development was planned never materialized. In 2015, the Latvian government purchased the property back, with half of the property slated for use by the Latvian military to conduct training. In a twist of irony only the Cold War could create, Skrunda-1 may see new life as a training ground for increasingly wary Baltic countries facing a revanchist Russian neighbor.

Adam Maisel is a military intelligence officer in the Army National Guard and veteran of Operations Enduring Freedom and Freedom’s Sentinel. Previously, Adam served as a legislative assistant for the National Guard Association of the United States. The opinions expressed are his and his alone.

Will DuVal is a recent graduate of Santa Clara University and an Army Reserve Military Intelligence Officer assigned to the 304th Information Operations Battalion in northern California. He graduated with a Bachelor of Science in political science and international affairs with a minor in German studies, and has worked with the Truman National Security Project, U.S. Mission to NATO, and Office of the Assistant Secretary of Defense for Public Affairs as an intern.