Everything Old is New Again: Espionage and Stratagems in Ancient Iraq and Syria

As soon as man learned to create documents, he began to classify them. This is one of the many indications that intelligence gathering is as old as civilization itself. Techniques regarded as completely modern — such as classifying documents — have actually existed for thousands of years. In fact, the world’s oldest classified document is part of this story.

Unfortunately, much of the evidence for these operations comes from Iraq and Syria where, because of recent political events and wars, archaeological work is nearly impossible. Even locating objects already in museums has become much more difficult than before. ISIL seems to spends as much time destroying artifacts as it does killing people. The best we can do is look at what remains and analyze what we have learned from the material that has already been dug up.

Two ancient cities in particular, Mari and Shubat Enlil, have provided us with a whole host of spy stories that illuminate how important intelligence was to ancient rulers as well as what techniques they used to collect, analyze, and disseminate the information they needed.

The Evidence from Mari

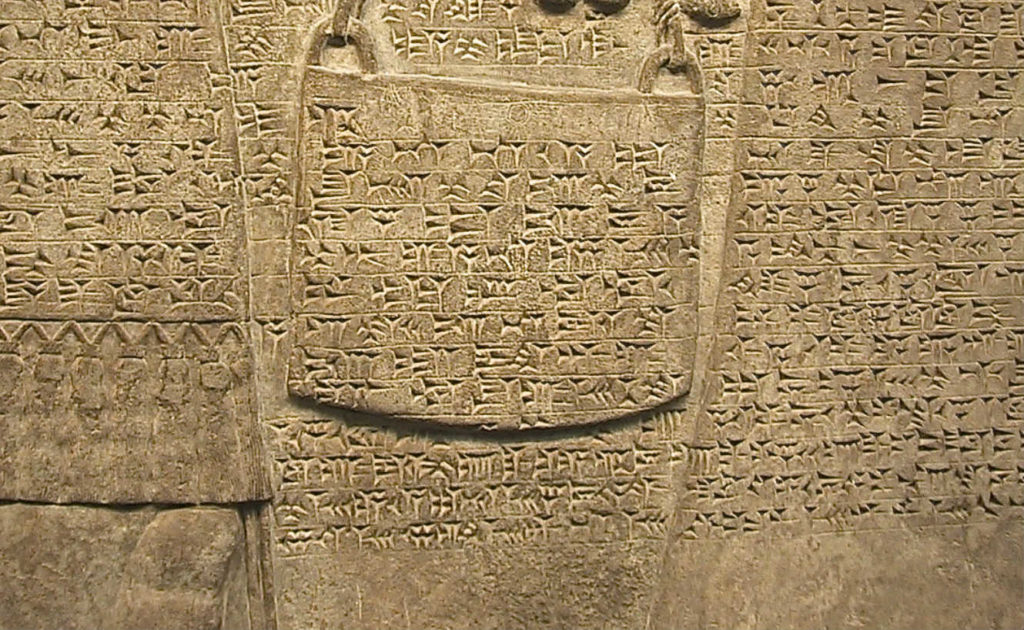

The city-state of Mari is in Syria on the east bank of the Euphrates River about 10 miles north of the Iraqi frontier. French archaeologists uncovered thousands of tablets from its royal archives. The documents are letters in cuneiform that were sent or received by the kings of Mari and their o. The first thing we discover by reading these letters is that Mari’s relationship with its neighbors was complex and much of its diplomatic activity was conducted clandestinely.

The rivalry between the dynasties of Mari provides abundant examples of remarkably modern stratagems and intelligence activities. Not surprisingly, our story begins with a conspiracy. In about 1813 BCE a man named Shamshi-Adad successfully schemed to overthrow the dynasty of Zimri-Lim and take control of the region around Mari. Once he succeeded, Shamshi-Adad put his son Yasmakh Adad on the throne of Mari while he ruled from a place called Shubat Enlil (more on this location later). His other son, Ishme-Dagan, was made ruler of the city of Ekallatum.

Accordingly, he sent a stream of letters to his sons with advice on military matters. These letters are now available in a series of books from Peeters Publishers. In these we see Shamsi-Adad’s instruction on how to surprise enemies, how to stage an ambush, and how to set up deception operations — all activities that relied on gaining intelligence quickly and acting on it. Without such intelligence, there could be no effective coordinated efforts between the three kings. One of his letters pretty much summed up the state of military affairs in this theater of operation and did it in remarkably modern terms:

All of you are constantly trying tricks (stratagems) and maneuvering endlessly to destroy the enemy. The enemy likewise constantly tries tricks and endlessly maneuvers against you, just as wrestlers try to trick one another all the time . . . I hope that the enemy will not maneuver you into an ambush.

Shamshi-Adad never missed an opportunity to lure an unsuspecting foe into a trap. Of course, he wanted to teach his sons the same skills. They seemed to have learned their lessons. We have examples of the sons using deception operations, such as attacking a territory with a group of guerrillas formed by their own men disguised as the opposing force.

Mari: Spying and Propaganda

The bulk of the military intelligence that Shamsi-Adad’s forces needed was obtained through espionage. Diplomats and messengers on both sides were automatically assumed to be spying. There was even a tribe, the people of Zalmaqum, for whom spying was a specialty. Their informers were called “sa lisanim,” or “those willing to give information to the enemy.” Supposedly, they could not be trusted unless they were paid large sums of money — although why this would make them any more trustworthy is unclear and the sources say there was no guarantee that they would be effective or loyal.

Shamshi-Adad was also famous for dispatching propagandists who were known as “men of rumors.” When he decided to conquer Zalmaqum itself, he did so by using fifth-columnists. He recruited certain men to propagandize for him in advance or by spreading rumors of an advancing Assyrian army that scared the enemy into abandoning its positions. In one case, we know that propaganda operations conducted by only two soldiers were able to spread fear and caused troops to revolt.

Mari: Internal Security

Military affairs were not the only important subject for intelligence collection. Political assassinations and palace intrigues were commonplace. Thus, internal security received a great deal of intelligence attention, as well. As in most ancient societies, intelligence often came from the gods and consulting oracles was a way to determine what the gods knew. They believed that the deities, at times, offered advice to kings about their own safety. Such warnings could be quite specific. A goddess, speaking through a female priestess reportedly told the king:

They will test you in a rebellion. Protect yourself, your servants, your commissioners whom you love. Place (them) at your side. Cause them to stand (by you) so that they guard you. Do not even walk alone. As to those who will test you, I will deliver them into your hands.

Kings did not just depend on the gods for their security, however. The gods might be guarding the king, but a bodyguard had his utility as well. Kings also needed spies to test people’s loyalty. When ringleaders of a disturbance were caught, their fate was not an enviable one. One text speaks of a conspirator being beheaded. Another conspirator had his skull crushed. Being proactive and having your enemies assassinated was definitely an option, but one had to be careful to keep such orders secret so that the target did not find out ahead of time. One king gave such instructions for the elimination of an undesirable person:

Locate this man. If there is a ditch in the countryside or in the city, make this man disappear (into it). Whether he climbs to heaven or sinks to Hell, let no one see him (any more).

The document was marked “Secret” so that the execution order would not to be leaked to anyone lest the target hear about it and flee. Nor was the punishment light. It was extended to include the plotter’s entire household and his companions in crime. Both they and their possessions were often set on fire.

Despite the efforts of his security agents, in approximately 1782 BCE Shamshi-Adad was overthrown by the dynasty that he had displaced. Zimri-Lim took back the throne of Mari with the help of his father-in-law, Yarim-Lim, ruler of the Syrian kingdom of Yamhad (modern-day Aleppo). Not surprisingly, one of the documents from Mari says that he planned to take back the city by introducing spies into Shubat Enlil. We are still in the dark about the intelligence failure that allowed Shamshi Adad to be overthrown.

The Evidence from Shubat Enlil

More records of the rivalry between the Lim Dynasty and the family of Shamshi-Adad were found a few decades ago at a place called Shubat Enlil. Although Shubat Enlil is mentioned in the Bible, its remains were only discovered in 1978 when Professor Harvey Weiss of Yale University began excavating a site on the Habur plains of northern Syria. By 1985, Weiss’ team had uncovered a royal temple which contained tablets that identified the site as Shubat Enlil. Another 1,100 tablets were found in September and October of 1987, making this the largest single collection of written material found in northern Mesopotamia in more than half a century. According to the tablets, Shubat Enlil was Shamshi Adad’s capital.

Not surprisingly, among the first documents unearthed were reports of spy exchanges. The reports detail how Shamshi-Adad deployed spies called “scouts” or “eyes” to check up on both friends and enemies. Sometimes, spies on either side were captured. One of the documents is a treaty for a spy exchange. Important agents were often ransomed. (I’ve always imagined this happening on a bridge, at midnight).

Shamshi-Adad ordered the establishment of special bureau in the palace at Shubat Enlil to process the various types of clandestine information collected. The members of this bureau translated and analyzed captured documents, kept copies of secret dispatches, and generally, kept the king up-to-date on intelligence matters. Documents captured from the enemy did not always produce useful intelligence. One report says that four documents were captured from the enemy but they contained nothing of interest. Still, the agent forwarded them anyway.

We know the name of at least one head of this bureau. He was called Buqaqum, or “little gnat,” an appropriate nickname for someone who buzzes around the palace collecting information — the proverbial “fly on the wall.” He collected and evaluated intelligence from various governors, vassal states, gossipy merchants, wandering artisans, sailors, messengers, refugees, and even from the queen herself.

Conclusion

Shamshi-Adad’s death was a major blow to Shubat-Enlil, and in the tumultuous two decades that followed, neighboring princes and kings on the Habur Plains ransacked and pillaged Shubat Enlil and fought with each other over its spoils. It is also ironic to think that today the United States is desperately trying to collect intelligence about people on the ground in that area, just as local rulers were doing 4,000 years ago.

The city-states of Mesopotamia endured for a thousand years after Shamshi Adad’s death until they were overwhelmed by the Achaemenid Kings of Persia around 500 BCE. Because many of the cites were put to the torch, the sun-baked clay tablets were fired to a hardness that allowed them to survive for the next 2,000 years and, thus, allowed them to be found by modern archaeologists. Now, in the 21st century, Mesopotamians are still fighting Persians and, of course, ISIL occupies the plains of northern Syria. No one knows how much of the ancient evidence has been damaged or destroyed.

As for our secret document, I have spent years trying to locate a photo of the original tablet. The French scholars in charge of the publications of the documents in Paris could not produce a copy. The volume that was supposed to contain a transcription was missing at the Library of Congress, although I am told one can access it at the Bishop Payne Library of the Virginia Theological Seminary in Alexandria, Virginia.

A more elegant solution would be to go see the original tablet at the National Museum at Aleppo in Syria. Even if one wanted to dodge bombs and sniper bullets to get to it, one would not access to the tablets. These days, the museum looks

It would seem that after 4,000 years, the document remains classified!

Col. Rose Mary Sheldon holds the Burgwyn Chair in Military History at the Virginia Military Institute. An extended version of this article can be seen in: R.M. Sheldon “Spying in Mesopotamia. The World’s Oldest Classified Documents [pdf],” Studies in Intelligence 33, 1 (1989), pp. 7-12.