Join War on the Rocks and gain access to content trusted by policymakers, military leaders, and strategic thinkers worldwide.

“At once ride for Mosul. The Kurds are devouring one another like wolves. This must be stopped”

-Written order by Tahsin Pasha, Ottoman Principal Palace Secretary to Ebubekir Hazim Bey, the newly appointed Vali to Mosul, 1898.

By 1897, the feud between various Kurdish tribes of the Ottoman vilayet of Mosul had reached a troubling enough level that the palace decided replace the vali (governor) of the province. The Kurdish Artusiyah, Owramarah and Kahariyeh tribes were locked in a war over eminence. The chieftain of the Artusiyah tribe – Haji Agha – was a regimental commander within the Hamidiye cavalry irregulars, endorsed directly by Sultan Abdulhamid II to provide security in eastern Anatolia. In the sultan’s view, his own commanders were incompetent and not up to the task. While the logic of the Hamidiye regiments was to create a new source of rural power (mostly against Armenians), it destabilized the existing balance of power between Kurdish tribes themselves, deepening rifts between tthem. With the balance of power between Kurdish tribes — as well as Kurdish religious leaders (sheiks) and tribal leaders (agas) — disrupted, the Sublime Porte had to intervene.

Local Ottoman officials and military commanders watched warily as disorder spread even further. However, they had to be careful when intervening in tribal conflicts that involved Hamidiye regiment chieftains. If they punished these leaders, they could face the wrath of the sultan himself who was loathe to compromise a force he saw as necessary to counterbalance against the Armenians. The imperial administration’s inability to contain the feud of the Kurdish tribes around Mosul intensified and generated sufficient disdain against the empire that later on, British and Russian involvement in the region became strategically easier through playing these existing rivalries against the Ottoman state and against each other. The fact that the Ottomans had ruled the area for more than 400 years did not insulate them from the tribal troubles of Mosul and the wider regional-strategic problems brought by the city’s instability.

Perhaps predictably, the newly appointed governor Ebubekir Hazim bey would fail in bringing order to Mosul’s hinterland. He was replaced, and his successors were proved to be more ambitious or more heavy-handed. Under their leadership, the Ottoman administration became even more deeply entangled in tribal, sectarian and ethnic feuds and often conflicting administrative orders.

Over a century later, as we watch fragile coalition of forces approach Mosul to oust a gang of religious fanatics, this divided vilayet remains a source of profound problems for its rulers.

Late last year, I wrote an article on Turkey’s historical and strategic interests in Mosul. My main argument was two-fold: First, Turkey’s involvement in Mosul is not motivated by “sectarian” concerns, nor does it reflect an “Ottomanist” phantom limb. Rather, it is rooted in early Turkish-nationalist orthodoxy, which held that Mosul was a part of the Turkish Republic. Second, there are pragmatic and tangibly strategic considerations for Turkey’s involvement in Mosul, chiefly, the surveillance of supply and transportation corridors of the outlawed Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK). The defense of Turkey’s rugged southeastern highlands starts in Mosul. That’s why I depicted Mosul as Turkey’s “Fulda Gap” — the strategic corridor that served as one of the primary chokepoints between East and West Germany during the Cold War.

The purpose of Fulda Gap analogy was important. Mosul, just like that Cold War chokepoint, represented the pivot for the defense of a much larger geography around itself. With the fall of Mosul to the Islamic state of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL) in 2014, Turkey lost its primary forward intelligence network. Regaining that foothold has since been Ankara’s priority. This explains its seeming “stubbornness” in insisting on joining the war, its retention of a training camp in Ba’shiqa, and its various other actions to regain its foothold in Mosul, even in the face of open hostility from Baghdad. I also warned that Turkey’s forward operating bases in the wider northern Iraqi region were in danger of envelopment through three main strategic access zones: Iraqi-Kurdish (PKK), Syrian-Kurdish (YPG), and ISIL from the south. These bases faced a dangerous risk of being overrun either by ISIL, the Iraqi Army, or Shiite militiamen.

Since this article was published, three major strategic changes took place. First, a major strategic re-posturing by Russia in Syria combined with the steady pressure of U.S. and coalition airstrikes pushed ISIL from an offensive posture to a defensive posture. Russian operations also increased tensions within the anti-ISIL coalition by raising the costs of intervention. While Russia’s heavy-handed approach in Syria has hurt ISIL, Jabhat al-Nusra, “mainstream” rebel groups, and civilians alike, it has also turned both Syria and Iraq into extensions of NATO’s wider escalation with Russia in the Arctic, Baltics, and the Black Sea. Furthermore, Russia is now undeniably a major player in any post-war settlement in Syria and Iraq.

Second, U.S. diplomacy gradually mustered a marriage of convenience between Iraqi Security Forces, Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG) peshmerga, Sunni Arab paramilitaries, and Shia volunteers for the Mosul campaign. The U.S.-designed operational directives are laid out very clearly with the aim of preventing jurisdictional and spatial conflicts. There are endless criticisms that can be laid out against how fragile this coalition may be, but at least for the time being, it seems to be working. Third, a coup attempt in Turkey has led to an abundance of confusion over loyalties within the armed forces, which has rather paradoxically generated increasing willingness to participate in operations in Syria and Iraq. Ankara remains defiant of calls to end Turkish involvement in both theaters. President Recep Tayyip Erdogan specifically asserted that Turkey’s borders need to be reconsidered in Iraq and Syria based on regional power balance in the 1920s and right now, with a specific eye on Mosul.

It seems inevitable that Mosul will be liberated from ISIL, but how it is to be liberated will have a major impact on the strategic landscape in the Middle East. Many observers of different stripes have already offered their different perspectives on the conflict. It is important for all concerned to understand that regardless of which ethnic or sectarian group dominates Mosul’s administration after the war, three structural aspects will shape the city’s strategic hinterland: population, demography, hydrocarbons, and water. As a consequence, once the war is over, it will be impossible for Mosul’s new administration to avoid the gravitational pull of the KRG and thus be heavily influenced by the Kurds of Northern Iraq. This is first true in terms of population, due to Kirkuk and Erbil. Second, Mosul will play a key part in any future pipeline project that seeks to export KRG natural gas to European markets. And third, all the dams that supply water to Mosul through the Tigris river are also controlled by the KRG. In other words, even though Baghdad and Shia militias may seek to counterbalance against the Sunnis in Mosul in post-war setting, their ability to do so will be heavily dependent on the KRG’s control of almost every strategic resource Mosul needs.

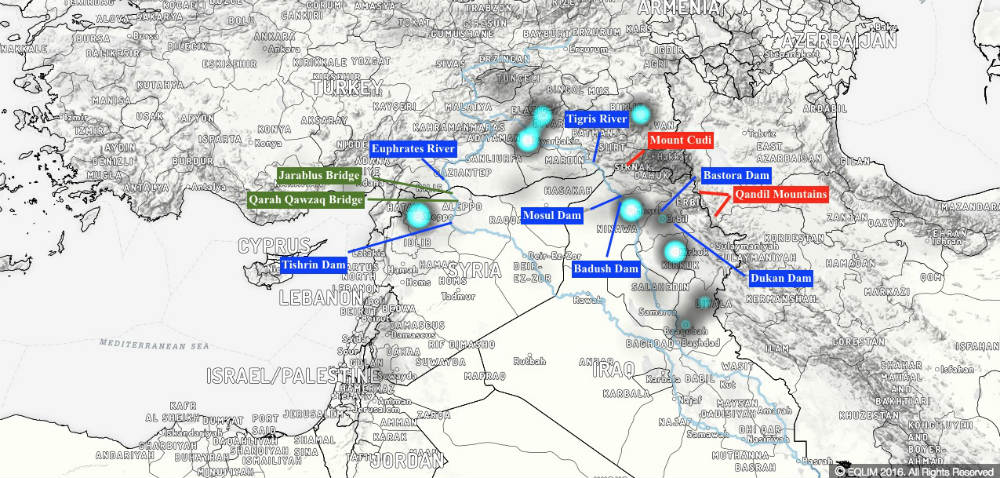

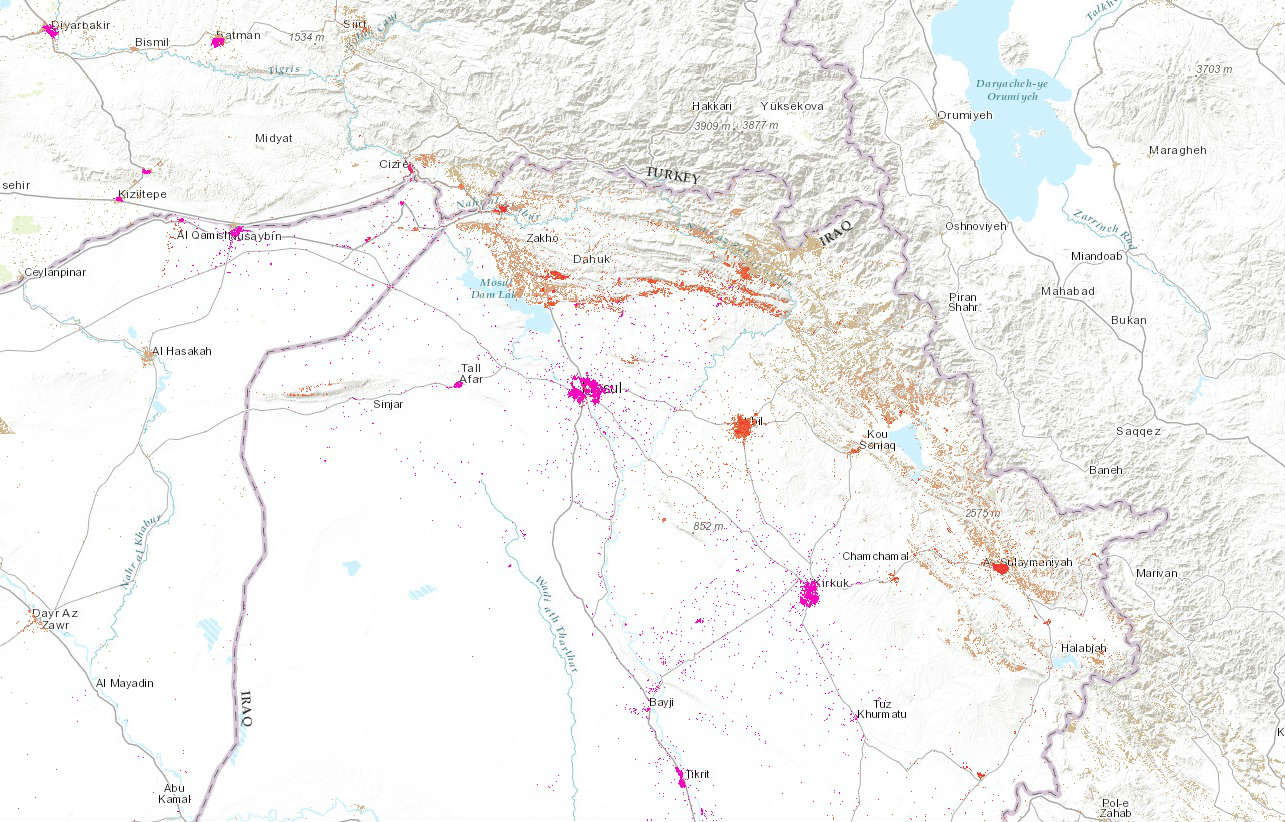

In a previous geospatial analysis conducted with the Eqlim risk intelligence group, I examined Kurdish armed movements across Syria and Iraq from 2014 to 2016. I reached three main conclusions. First, the Kurds of Syria and Iraq have secured enough oil reserves, mid-stream infrastructure, waterways, dams, and bridges to secure long-term administrative resources within their respective borders.

Major conflict flashpoints that involved Kurdish armed groups; February – August 2014, with major geographic and waterway locations imposed. Source: Unver, A. ‘Schrödinger’s Kurds: Transnational Kurdish Geopolitics in the Age of Shifting Borders’, Journal of International Affairs, Spring/Summer 2016, Vol. 69, No. 2

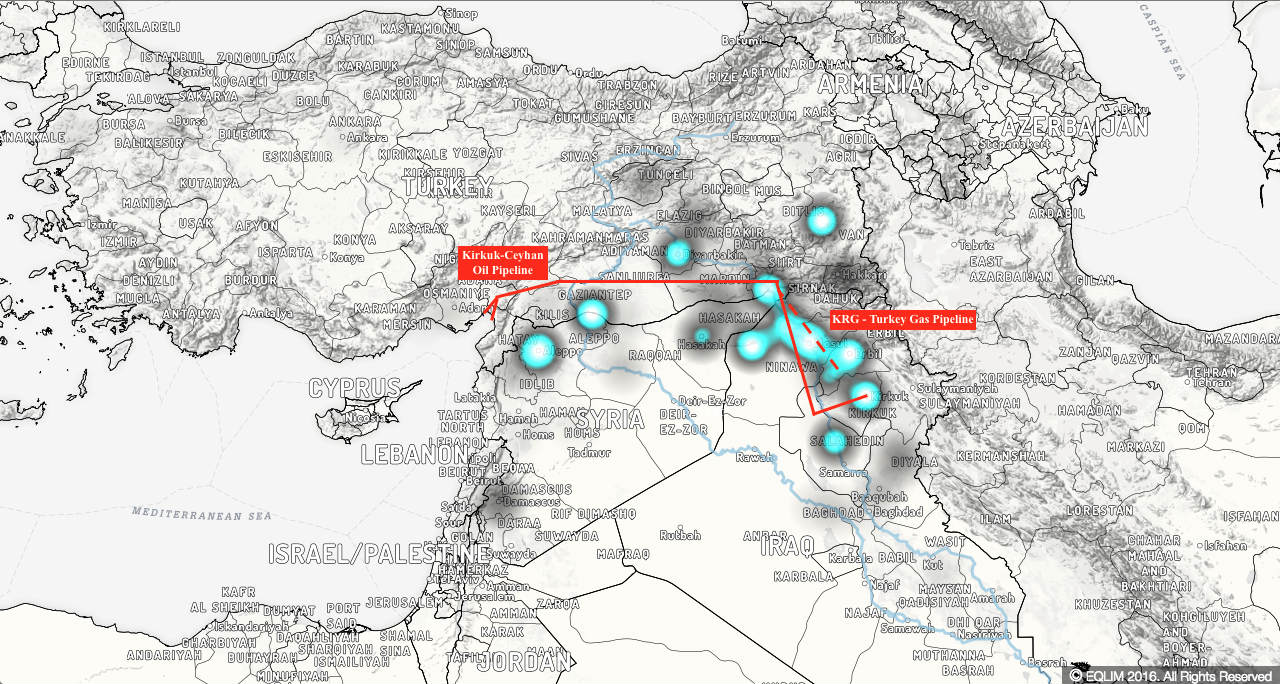

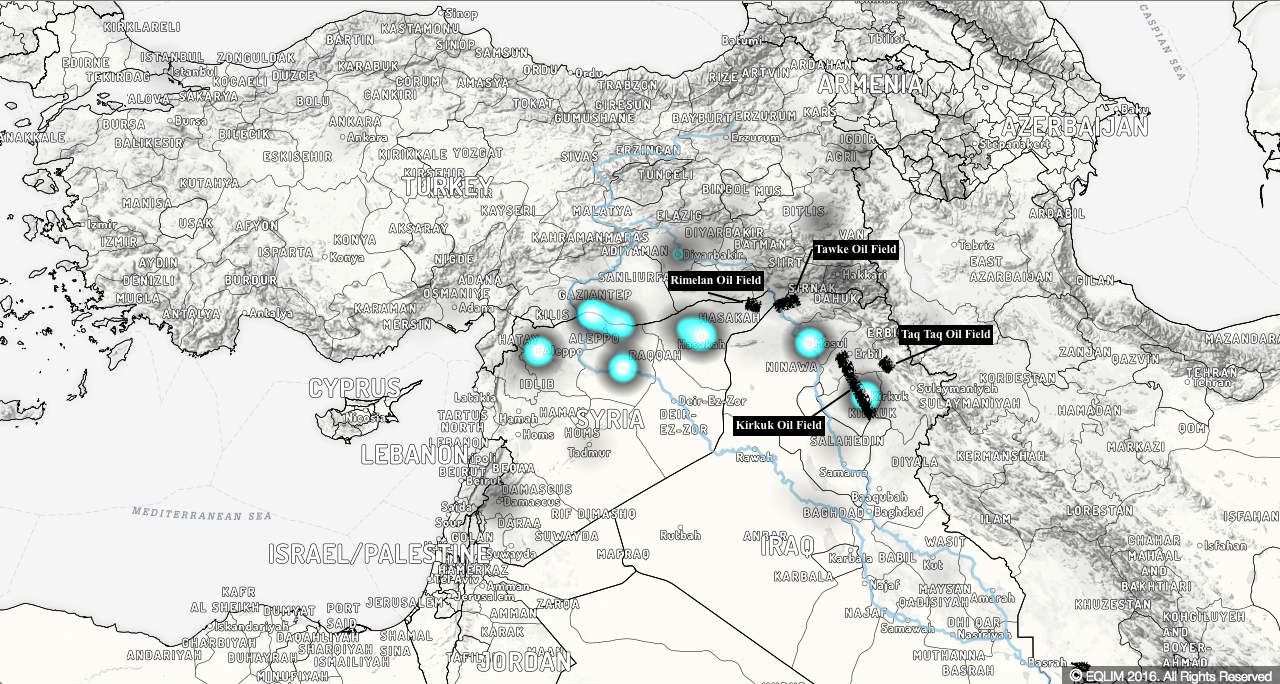

Second, conflict data indicates that through the second half of 2014 (soon after the fall of Mosul to ISIL), the peshmerga prioritized oil and proposed natural gas mid-stream infrastructure in picking their battles with the ISIL. During this period, the peshmerga’s retreat from Mosul took place along Iraqi-Turkey Pipeline (ITP) and the proposed KRG-Turkey natural gas pipeline, in addition to their defense of highways leading to the Kirkuk, Taq Taq, and Tawke oil fields.

Major conflict flashpoints that involved Kurdish armed groups; August 2014 – August 2015, with major oil and gas reserve and mid-stream infrastructure imposed. Source: Unver, A. ‘Schrödinger’s Kurds: Transnational Kurdish Geopolitics in the Age of Shifting Borders’, Journal of International Affairs, Spring/Summer 2016, Vol. 69, No. 2

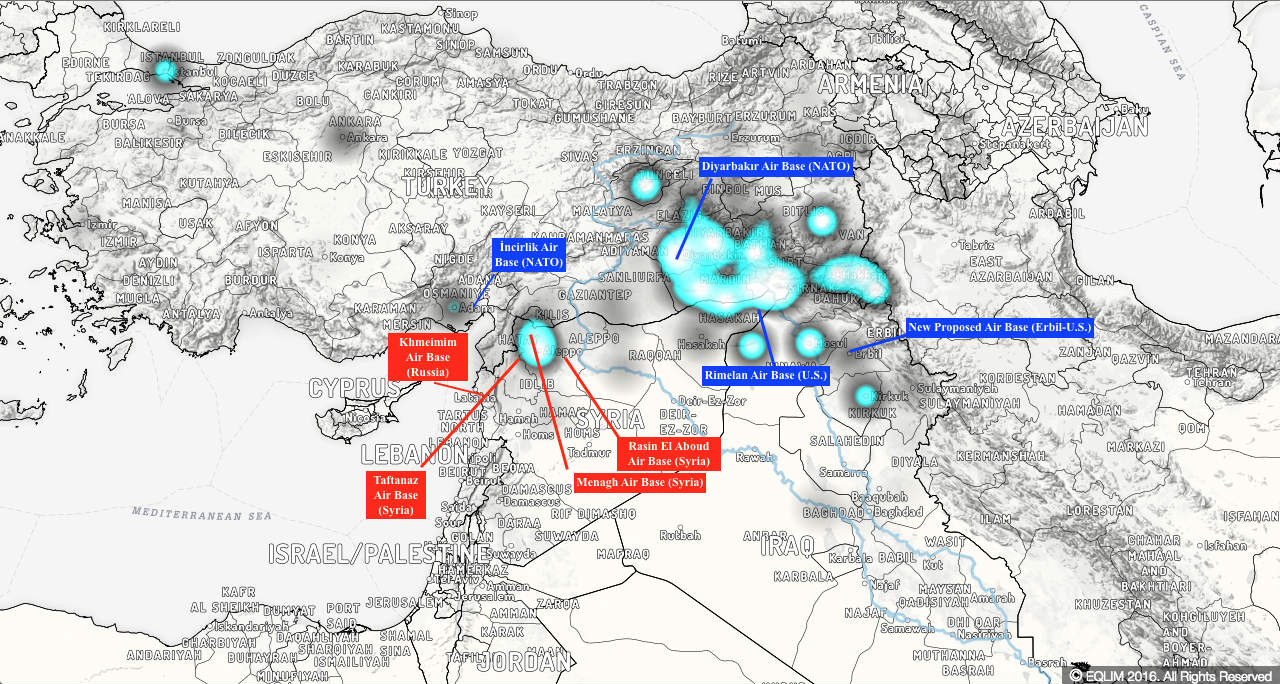

Finally, the study demonstrated how Iraq and Syria are being divided into two main air superiority zones between NATO and Russia, composed of the U.S.-controlled airbases of İncirlik, Diyarbakır, Rimelan, and Erbil and the Russian-controlled airbases in Khmeimim, Kwairis, and Menagh. Conflict activity zones are almost entirely enveloped by competing air control zones.

Major conflict flashpoints that involved Kurdish armed groups; August 2015 – February 2016, with US and Russian controlled air bases. Source: Unver, A. ‘Schrödinger’s Kurds: Transnational Kurdish Geopolitics in the Age of Shifting Borders’, Journal of International Affairs, Spring/Summer 2016, Vol. 69, No. 2

I’m grateful to my colleague Dr. Metin Gürcan for reminding me that Russia’s decision to launch a barrage of cruise missiles from its warships in the Caspian Sea in early October 2015 and the exact trajectory of these missiles were intended to directly challenge CENTCOM’s claim of aerial superiority.

How does this data inform us about the wider implications of Mosul?

While active conflicts render accurate population analytics very difficult, there are two things that can be said through Mosul’s population in proportion to other cities in its proximity. First, it is a Winterfell of sorts, the main political and population hub of the north and by different counts, the second-largest city in Iraq. In addition, it stands adjacent to three other major centers of population gravity in the north, along with Kirkuk, Sulaymaniyah, and Erbil. Whatever group ends up administering the city after ISIL will sit next to three major Iraqi Kurdish population centers and atop a predominantly Sunni environment. That’s why any post-war settlement — at least from a population approach — must provide Sunnis and Kurds with a better deal than they had before the city’s fall in 2014. As mentioned in my previous article on Mosul, the city isn’t merely the second largest city in Iraq, but it is also the logistics and transportation hub between Iraq’s fourth- and fifth-biggest cities (Erbil and Kirkuk) and also highway-accessible to the sixth-biggest city (Sulaymaniyah). From a logistics point of view, this means that highways that lead to Mosul control the transportation and supply of more than half of Iraq’s population. The population-related implications of this lead to the main position of Turkey, which argues that post-war Mosul must be administered either by Sunnis or by a joint administration that reflects their numerical superiority.

Population density around the Syrian, Iraqi, Iranian and Turkish border. Source: Author’s work, using ArcGis base map and Esri’s World Population Estimate geospatial dataset

Yet the greater concern is whether Mosul’s next administration will have the capacity or the willingness to address sustained humanitarian crisis in its vicinity. If the Mosul coalition doesn’t succumb to infighting and succeed in mustering a mutually agreed power-sharing agreement, will it be sufficiently positioned to take back refugees into the city, establish order, and continue services provision as soon as victory is declared? The day after the battle ends, the functioning of bakeries, the provision of electricity and running water, and the resumption of basic economic activities and their equitable administration between different religious and ethnic groups will be the real test for Mosul. With regard to the most essential service to the city — water supply — it is important to underline that the Dohuk, Bastora, and Mosul dams that control the southbound flow of the Tigris River are all controlled by the KRG, again rendering the Kurds a key player.

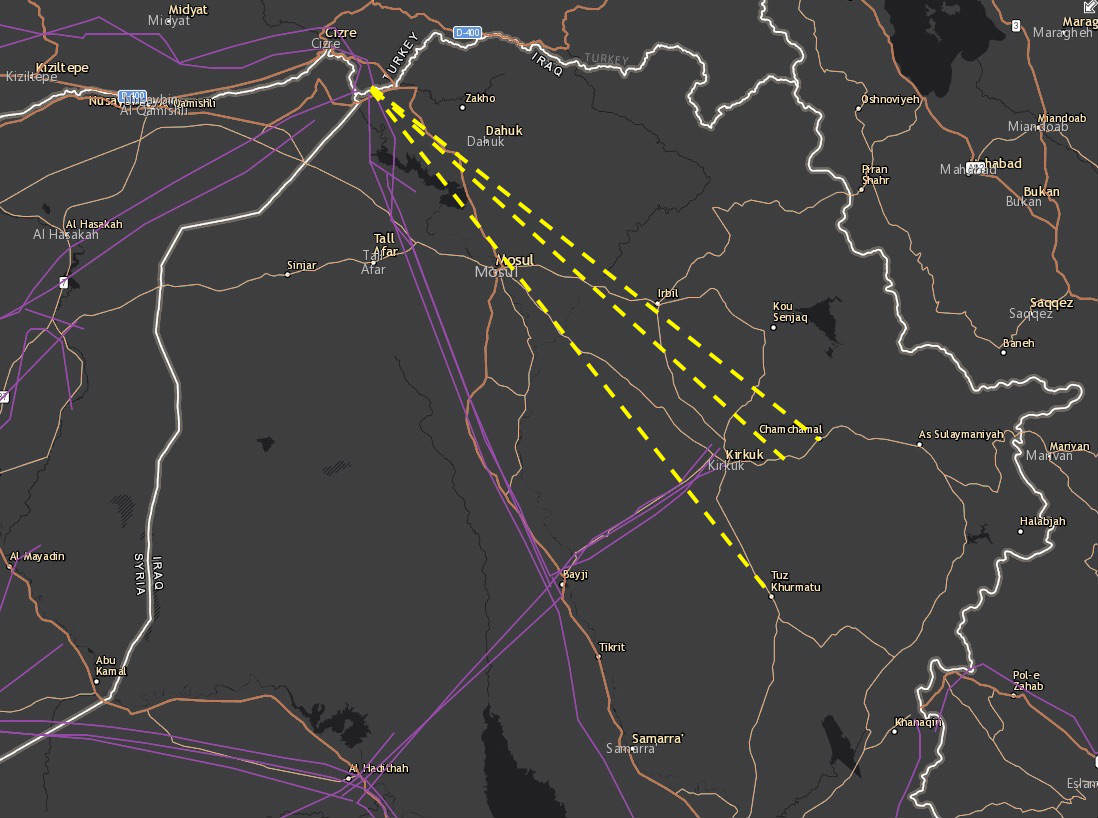

As mentioned earlier, oil fields, pipelines, and refineries have been the peshmerga’s primary defensive priorities in the aftermath of Mosul’s fall to ISIL in 2014. Quite interestingly, the peshmerga’s main battle activity heat graphs consolidate along the northern section of the Iraqi-Turkish Pipeline (ITP) and the predicted trajectory of the KRG-Turkey natural gas pipeline, whose construction began in January 2016. In addition, though Mosul’s highways today connect the Tawke, Taq Taq, and Kirkuk oil fields, Mosul itself also lies at the center of any future pipeline trajectory that can connect the gas fields of Chamchamal, Tuz Khurmatu, and Khor Mor. After Mosul’s liberation, the security threat to the ITP will also diminish, leading to the re-continuation of Iraqi oil flows into Turkey and the addition of new midstream infrastructure that can connect new fields to a northbound pipeline network.

Purple lines indicate existing oil mid-stream infrastructure with pipelines and pumping stations. Yellow dashed lines indicate probable gas pipeline routes connecting Chamchamal, Tuz Kurmat and Khor Mor gas fields. Light and dark orange lines show minor and major highways in the region. Source: Author’s work, using ArcGis base map and Esri’s Persian Gulf and Caspian Sea Existing and Proposed Gas and Oil Pipelines geospatial dataset

This is a fundamentally important fact, and one closely tied to the bigger question of how to export Kurdish gas over the long term. While the natural gas reserve balance is tipped strongly in favour of the KRG, Syrian Kurds have long entertained the idea of exporting that gas not through Turkey, but rather through Rojava and into the Mediterranean. Turkey’s Euphrates Shield operation has largely prevented this prospect and kept existing midstream infrastructure that passes through Silopi, Turkey the most logical (but often dangerous) route for KRG gas exports to Europe.

Pipeline geopolitics and existing hydrocarbon reserves around Mosul are thus a part of the wider question of whether such reserves can be exported to Europe through Turkey, through Iran into an eastbound route, or whether they are incorporated into oil/gas-for-electricity arrangement with Tehran. This adds to the existing tensions between Turkey and Iran over Mosul and pulls in Europe (as a natural gas consumer) and Russia (as a natural gas producer). Moscow views any gas source or transit route that challenges Russia’s monopoly over European demand as a national security risk. That’s why Russia has tried to shut down any project that includes an alternative source of gas for Europe, focusing instead on pushing projects that offer transit alternative to Ukraine. Nordstream II and Turkish Stream are manifestations of this strategy. A liberated Mosul, through its ideal location of connecting different Iraqi gas reserves to Turkey, is viewed with similar suspicion.

Conclusion

Much will depend on how Mosul is liberated and how conclusively the post-battle leadership of the city can switch from fighting into administering. The city’s demographic composition, along with its location between different and competing demographics renders critical adequate basic services, humanitarian aid, and relief provision to all demographic groups in and around the city without generating new forms of grievance that sustain the conflict. A crucial next step will be how to handle Sunnis that were once part of ISIL, but seek rehabilitation and reintegration into Iraqi society. This task is further exacerbated by the fact that ISIL may retain an underground network in the city, disguised as refugees or people seeking amnesty, in an attempt to generate social tensions that test the stability of the post-war administration in Mosul. Water is a crucial factor and, given its control of the Tigris dams, the KRG is best suited for the provision of running and drinking water to the city, which amplifies its standing in Mosul’s administration after the city’s liberation.

The relevance of hydrocarbons to Mosul is both technical and a political. The most rational pipeline trajectory to connect northern Iraqi/Kurdish oil and gas fields goes through Turkey. This is also a financially advantageous option, as both Erbil and Baghdad can get the best deal for the export of their gas to Europe. This specifically puts the question of Mosul into the radar of Russia, which would support an Iran-bound pipeline and an export option for the gas fields within the KRG. There will be an inevitable clash between the European Union and Russia over these resources in the months following Mosul’s liberation.

Akın Ünver (akin.unver@khas.edu.tr) is an assistant professor of international relations at Kadir University, Istanbul and the author of Defining Turkey’s Kurdish Question: Discourse and Politics Since 1990(Routledge Studies in Middle Eastern Politics, 2015)