Andrew Jackson’s Marco Polo

Andrew Jampoler, Embassy to the Eastern Courts: America‘s Secret First Pivot toward Asia, 1832-37 (U.S. Naval Institute Press, 2015).

President Andrew Jackson (1829-1837), a former general of the militia and slave owner in Tennessee, remains best known for democratizing American politics, opposing the Second Bank of the United States, and presiding over Indian Removal in the 1830s. But, he also supported New England investors and merchants’ reaching out into Asia and the Indian Ocean world and, thus, had a global side. Jackson dispatched envoy Edmund Quincy Roberts (1784-1836) and a handful U.S. Navy warships on a mission to formalize American relations with the Sultan of Oman, who ruled Zanzibar and controlled parts of the East African trade through it. He also sought out the king of Thailand in Southeast Asia. This tale is told in a stirring new book by maritime historian Capt. Andrew Jampoler (U.S. Navy, ret.).

Roberts had met Sultan of Oman Sayyid Sa’id bin Sultan while trading in Zanzibar in 1828. The two hit it off. When Roberts returned to the United States, he persuaded the Jackson administration to send him back to negotiate an official trade agreement with the sultan. The administration sent him several years later, in March 1832. He returned in May 1834 with draft treaties that he had worked out with the sultan and the king of Thailand as well. The administration was able to ratify these agreements and send Roberts back again to deliver them in April 1835. Roberts became ill and died in Macao on the way home, in June 1836, but his mission succeeded: The United States had established formal relations and trade agreements with Oman and Thailand and had taken its first major steps into Asia and the Indian Ocean.

Roberts’ mission indeed represented America’s first pivot toward Asia. This occurred within the context of New Englanders’ difficulties trading within the European-dominated Atlantic and Caribbean regions in the early 19th century, which historian Frank Lambert illustrated in another book. The Jackson administration kept Roberts’ mission secret in order to avoid showing its hand to Britain, whose presence and influence were growing in the Indian Ocean at the time. Thus there was another, more worldly, side to Andrew Jackson.

Jackson intended to use Roberts’ mission not only to advance American trade interests, but also to present the United States as different than the European powers, and to begin cultivating goodwill and even secure friendly ports and possibly naval bases in Asia and the Indian Ocean. The secretary of state instructed Roberts to stress that “we are not ambitious of conquest…we desire no colonial possessions…we seek a free and friendly intercourse with all the World” in his talks. He further told him to “endeavor to remove the fears and prejudices which may have been generated by the encroachments or aggressions of European Powers.” The administration was well aware of the cross-cultural difficulties Westerners were encountering in that part of the world, particularly in Japan, China, and Southeast Asia. The secretary nevertheless ordered Roberts to

accommodate yourself to the peculiar notions and customs of the country, however absurd they may be, whenever you can do so without such acknowledgement of inferiority as would be incompatible with the dignity of your Government.

Roberts’ mission succeeded brilliantly in Oman, leading not only to mutual recognition and a trade agreement that allowed New Englanders to exchange textiles and other products for East African ivory, dyes, and other exotic exports. The mission also cultivated the sultan’s goodwill toward the United States. The sultan confirmed as much in his letter to “the most high and mighty Andrew Jackson, president of the United States of America, whose name shines with so much splendor throughout the world.” He reconfirmed this when Al Sultana, the first Omani merchant vessel to dock in New York harbor, arrived carrying gifts for Jackson’s successor, President Martin Van Buren (1837-1841). These gifts included two stallions and several bags of pearls. Thanks to friendly advice from Americans back in Oman, the gifts did not include the two women the sultan had wished to send the president from his own harem, which included about 40 Arabians, Circassians, and Greeks.

Roberts also succeeded in Thailand, but he enjoyed no success elsewhere in Southeast Asia, and he did not survive to make it to Japan. In July 1853, Commodore Matthew Perry did, marking the height of America’s attempt to gain influence in and around Asia and the Indian Ocean in the decades before the Civil War. After that conflict, the United States encountered a different region, finding a modern, imperial Japan and a British Empire firmly entrenched there. Americans focused on their political, naval, and commercial interests in the Caribbean and the Pacific thereafter.

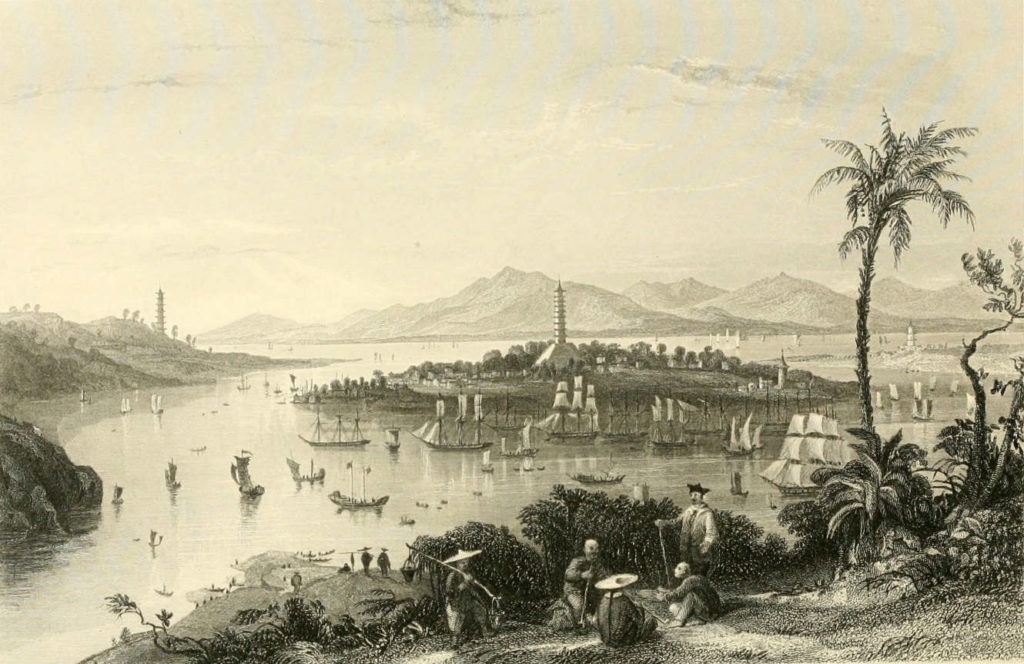

Jampoler reconstructs Roberts’ two-part mission in Embassy to the Eastern Courts: America‘s Secret First Pivot toward Asia, 1832-37. Jampoler cites official instructions from the Department of State and the Department of the Navy to Roberts and the officers who escorted him, as well as ships’ logs and travelogues while telling his story. He also fills the book with very fine illustrations, including photographs, paintings, and naval charts from the era. These illustrations alone make Jampoler’s book worth the price.

Beyond this stirring story of American diplomacy and trade, Jampoler’s book illuminates the U.S. Navy and its problems in the age of sail. The American navy was small, but dignified, compared to its European counterparts in the 1830s. Its several missions included scientific exploration and mapping, supporting trade missions, and projecting what power and influence it could to protect American expatriate traders from unfriendly acts, including piracy.

Roberts’ missions were around-the-world cruises. The Panama Canal would not exist until the next century, so Roberts had to sail from the American east coast to Brazil, then across the Atlantic to Africa and around the Cape of Good Hope into the Indian Ocean before coming back the same way. Thus is what he did on his first cruise. On his second cruise, he took the same route into the Indian Ocean, but then shot across the Pacific to California and from there down the west coast of South America, through the Magellan Straits, and back to the American east coast via Argentina and Brazil. Communications to and from Washington while at sea were painfully slow. Ships sometimes ran aground or sank due to incomplete or inaccurate charts and bad weather. Indeed, Roberts’ ship, USS Peacock, struck a hard reef in the Masirah Channel near the Arabian coast in September 1835. The sultan sent help and Peacock limped to a shipyard in India before continuing on. Sickness and disease also killed many. And most commanders had to deal with a ten percent or so desertion rate while deployed.

Jampoler could have improved his book, making it more history and less travelogue, if he had written a chapter surveying the global situation and offering world-historical background before reconstructing the trade mission. As it is, this background tends to appear throughout the story, often sidetracking the author, such as the three pages on the Spanish Empire in the Philippines from the 16th to 19th centuries that appear when Roberts’ ships arrive in Manila. He could also have written more for a present-day audience with respect to place names. The ships’ logs he read may have referred to “Buenos Ayres,” “Cochin China,” and “Monte Video,” for instance, but it makes for easier reading if authors silently correct for this and use Buenos Aires, Vietnam, and Montevideo in the text. This being said, I found Embassy a real pleasure to read, and I recommend it to anyone interested in America and the world through maritime history, cross-cultural trade, or the U.S. Navy in the age of sail. It reads like a good Patrick O’Brian story, and, having enjoyed those too, I am looking forward to getting my hands on more of Jampoler’s histories.

James Lockhart is Assistant Professor of History at the American University in Dubai, specializing in American foreign relations and international studies. He is broadly trained in world affairs, global and transnational history, and comparative analysis, with interdisciplinary area expertise in the United States, Latin America, and the Near East, and subject interest in the Cold War, the post-Cold War world, and intelligence history.

Image: Public domain