A Close Air Support Flyoff Is a Distraction

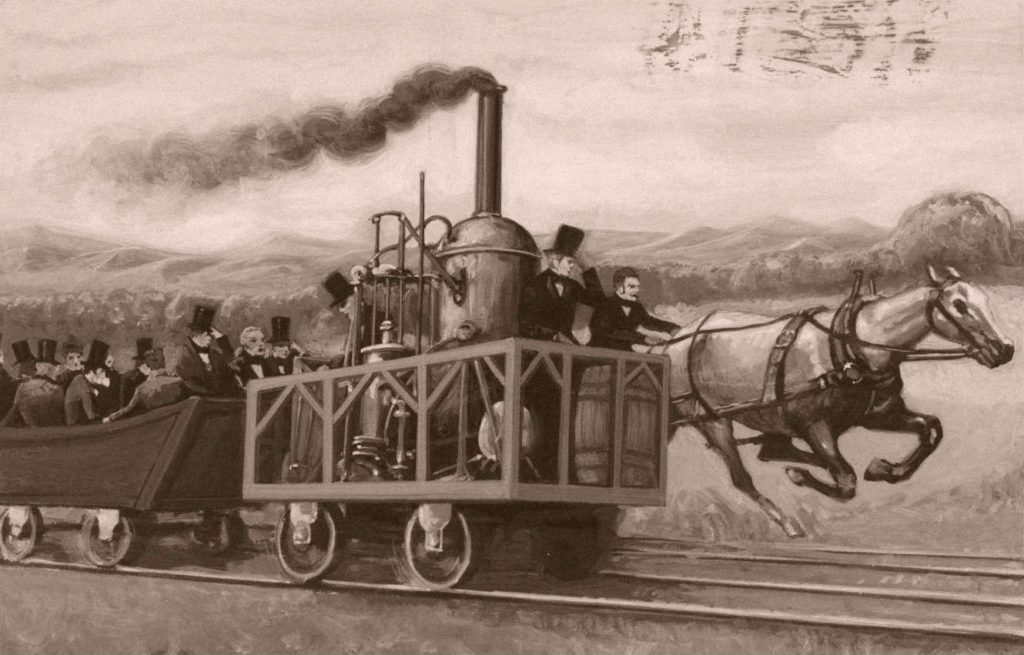

In 1830, the scions of the Baltimore and Ohio railroad staged a competition between the first U.S. built locomotive and a horse. The horse won. The victory was emotional, well-publicized, and even well-received. It was also irrelevant, at least as to the adoption of the locomotive. While horses continued to be an indispensable part of American commerce, they could not, and did not, supplant the locomotive as the centerpiece of industrial progress.

Just as the train versus horse race in 1830 didn’t actually resolve anything as to what the future would look like, our present day tactical airpower’s mother of all red herrings — the proposed capabilities comparison flyoff between the F-35 and the A-10 — is a highly emotional but largely irrelevant (and misleading) competition. Inside the beltway, Rep. Martha McSally, a former A-10 pilot and squadron commander (and present advocate for a constituency that includes bases that fly the A-10), argues forcefully for a flyoff. She is joined by numerous commentators, such as Jim Hasik at the Brent Scowcroft Center for International Security, who make very lucid arguments that critical results will be unveiled with far-reaching implications for U.S. tactical airpower. However, with due respect to the well-reasoned analyses provided by these advocates, the truth is that we already know everything we need to know about the capabilities of each aircraft in the U.S. inventory that does close air support (CAS). As such, a flyoff would be a needless distraction from the real issues facing decision-makers who must prioritize among many vital airpower-related missions.

The A-10 is the world’s finest Air Force tactical fighter for performing traditional CAS in an uncontested air environment. No one wearing a flight suit in the Air Force, indeed no one who is knowledgeable about airpower, will argue this point. Consequently, as it pertains to the current budgetary debate and the F-35 vs A-10 “controversy”, the point is irrelevant. Here’s why:

Close air support is a fire support mission, not a platform. The U.S. military supports and protects troops in the field for this mission by utilizing the capabilities of multiple platforms. As described by Jacquelyn Schneider and Julia MacDonald, it is the CAS-mindnessness of the pilots supporting a CAS mission — not the airframe — that matters. Empirical data tells us that A-10s have performed approximately 1/5th of the CAS workload in America’s recent contingencies — the vast majority being tasked to multi-role platforms like the F-16, F-15E, and F/A-18. What this tells us is that while the “Hawg” is undoubtedly the best traditional CAS fighter, the drop-off in quality of effects from other fighters is negligible, provided that sufficient emphasis is placed on CAS training in those airframes that are performing the mission.

Pundits and policymakers have created a false choice between the F-35 and the A-10. Clearly, the Air Force needs both. The A-10 is a highly specialized CAS platform. The F-35, on the other hand, is the centerpiece of a multi-national mutual defense and deterrence strategy. As such, exercises such as the flyoff and arguments based on “warm fuzzies,” distract from what is really important. In our view, here’s the intellectually honest way to fight for the A-10.

The U.S. military needs the A-10 because every mission-capable fighter is needed to meet worldwide requirements. Sustaining fighter capacity entails squeezing out every last drop of utility from the entire legacy tactical fleet, including the A-10. Additionally, the Air Force has a fighter pilot manning shortfall that can only be corrected if there are enough cockpits to train and absorb new pilots.

A-10 proponents should, therefore, pivot to an argument that demands full and proper resourcing for the Air Force’s current and future fighter requirements. This includes sustaining all the iron we have now, funding potential A-10 successors, and applying intellectual rigor to innovate the future of CAS. Stop making this about the F-35 versus the A-10, and don’t make the Air Force choose which of its babies to kill. It’s a false choice, and a bad one, for national security.

Col. Don Kang works on the Air Staff in Washington, D.C. Previous to this assignment, he was the program manager for the Air National Guard’s tactical fighter fleet. Col. Kang flew F-16s in the Regular Air Force and the Air National Guard and is a U.S. Air Force Fighter Weapons School graduate. He is a graduate of the Air War College’s Grand Strategy Program. The views expressed here are his own and do not represent those of the Air Force, the Department of Defense, or the U.S. government.

Col. Rob Preston is a member of The Judge Advocate General Corps of the Air Force specializing in International and Operations Law. For the last several years, he has practiced Government Acquisition Law. Col. Preston is a former United States Marine Infantryman. He is a graduate of the Air War College’s Grand Strategy Program. The views expressed here are his own and do not represent those of the Air Force, the Department of Defense, or the U.S. government.