Saudi Arabia is a Good Ally? Get Real

President Obama’s awkward recent visit to Saudi Arabia reopened debate over whether the Kingdom is a good U.S. ally or not. Certainly, there is no shortage of commentators arguing in favor of a stronger U.S.-Saudi partnership, calling for Obama to reassure the Saudis and arguing that the alliance is vital to U.S. national security.

Unfortunately, such arguments ignore the many problems in the relationship, which has become extremely fraught. Congressional criticism of Saudi Arabia, once almost unthinkable, occurs with increasing frequency. Recent moves by Congress to pass legislation that would permit relatives of victims of the 9/11 attacks to sue the Saudi government have been met with fierce criticism from the Gulf, and an explicit threat by the Saudis to sell more than $750 million in U.S. assets if the bill passes. Nor is the White House immune to this trend. The Obama administration opposes the 9/11 bill, the president’s reservations about the U.S.-Saudi alliance are well-known, describing it in a recent foreign policy interview as “complicated.”

These tensions reflect a basic reality: Saudi Arabia may once have been a good ally, but today the relationship is toxic. Saudi actions are more often negative for U.S. policy objectives than positive. Rather than repairing the relationship, U.S. policymakers should reduce support for Saudi Arabia’s regional agenda.

In fact, even the use of the term “ally” to describe Saudi Arabia is inaccurate. Despite a long history of U.S. military support – including U.S. defense of the Kingdom during the first Gulf War – and cooperation on a variety of issues, there is no formal treaty alliance between the United States and Saudi Arabia.

Yet, the use of the word “ally” is commonplace among those who argue that the Kingdom is a helpful, often indispensable partner for America’s Middle East policies. Indeed, historically, this was often true. The Saudis were staunchly anti-communist and partnered with the United States on various occasions to push back Soviet influence in the region, most prominently during the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan, which was interpreted (incorrectly) in Washington at the time as the beginning of a Soviet drive toward warm water ports in the Persian Gulf.

Saudi Arabia’s influential position in OPEC as the world’s swing producer of oil has also been beneficial to the United States in the past, though recent advances in shale drilling technology and continued low oil prices are reducing this influence. And in more recent years, Saudi Arabia has indeed been a helpful resource in the fight against terrorism.

But that isn’t the whole story. Despite the Saudi government’s participation in anti-terrorism, Saudi citizens remain a major source of terror financing. As U.S. Deputy National Security Advisor Ben Rhodes recently noted, the Saudi government has too often paid “insufficient attention” to preventing the flow of funds to extremist groups. At the same time, the Saudi government itself spends billions of dollars exporting the fundamentalist form of Sunni Islam known as Wahabbism. Saudi-funded madrassas in Pakistan, Afghanistan, and elsewhere have helped to produce the foot soldiers of violent jihadi movements from Al Qaeda to ISIL. Saudi Arabia may not be a direct sponsor of terror, but its citizens and policies indirectly provide the fuel for terrorist groups.

These problems have persisted in recent years: Over the last five years the Saudi government, focused on the overthrow of the Assad regime, did little to stop citizens from funding extremist groups inside Syria. Nor are they – despite claims to be the lynchpin of an anti-ISIL movement – contributing much to that fight. Though Gulf Cooperation Council countries initially participated in airstrikes against ISIL, military contributions largely ceased following the Saudi and U.A.E. intervention in Yemen’s civil war.

Proponents of a stronger partnership often obscure these issues by arguing that Iran remains the major threat to American interests in the region, necessitating continued U.S. support for Saudi Arabia. And it’s certainly true that Iran is a state sponsor of terror, and often a destabilizing force in the region. Yet this focus on Iran results in a form of “whataboutism,” a way to excuse the fact that Saudi Arabia is also, at times, destabilizing. In effect, we are told that Saudi Arabia may be bad, but Iran is worse!

This argument cannot actually excuse Saudi actions. In just the last few years, extensive Saudi involvement in Syria has worsened that conflict, as they provided arms and financing to a variety of rebel groups. A Saudi-led campaign has transformed the war in Yemen from a civil conflict into a major humanitarian crisis, one which has strengthened Al Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula.

Meanwhile, the recent Saudi decision to withdraw aid from the government of Lebanon may be excellent public relations material in the state’s ongoing campaign against Iranian influence, but the practical effectwill be to strengthen Hezbollah and weaken the ability of the Lebanese government to respond to the refugee crisis. On almost every front, Saudi Arabia is helping not to mend the post-Arab Spring Middle East, but to destabilize it.

Another argument for stronger partnership – that America’s support for Saudi Arabia is necessary because, otherwise, Iran is poised to dominate the region – is similarly misleading. The main basis for this narrative is Baghdad’s improved relationship with Tehran, itself less a result of Iranian aggression than of the 2003 U.S. invasion of Iraq. Meanwhile, Saudi Arabia’s military spending is almost double that of Iran – $632 billion to $397 billion in 2015 – and the Kingdom can claim friendship or common cause with the vast majority of the states in the region. Iran’s only major regional allies are war-torn Iraq, portions of tiny Lebanon and the besieged Assad regime in Syria.

Rather than strengthening the relationship with Saudi Arabia, therefore, U.S. policymakers should work with the Saudis where it is appropriate and avoid entanglement on other issues. This doesn’t necessarily imply closer cooperation with Iran. While the nuclear deal improved U.S.-Iranian relations, and there is potential for cooperation on issues like Syria, Iran has a long way to go before Washington considers it a viable partner.

Yet supporting Saudi Arabia’s quest for regional dominance, as many supporters of a stronger relationship have advocated, is likely to undermine many of America’s goals in the region. In encouraging the Saudi government to overextend itself – at the same time as it faces continued low oil prices, economic turmoil and sectarian tensions both domestically and abroad – Washington may be hastening domestic instability in the Kingdom, an outcome that is good for no one.

By providing arms sales, diplomatic and technical services for Saudi Arabia’s conflicts, the United States enables the very behavior which is so detrimental to regional stability. This is the rationale behind the bill advanced by Senators Rand Paul and Chris Murphy, which aims to limit munitions transfers to Saudi Arabia in protest of the humanitarian costs of the war in Yemen. In this and similar cases, officials should seriously consider whether our provision of arms or aid to Saudi Arabia is good for American interests or just Saudi ones.

Despite the negative press, Obama’s ambivalence towards Riyadh is the right approach. If Saudi Arabia has at times been a good ally, it has also often been a bad one. It may be a cliché, but like many people in deteriorating relationships, supporters of the Saudi alliance too often focus on the good times while ignoring the bad ones. Today, Saudi Arabia is not a good ally. U.S. policymakers would be wise to acknowledge this, and to focus on creating a less entangled, more transactional relationship with Saudi Arabia.

Emma Ashford is a Research Fellow in Defense and Foreign Policy Studies at the Cato Institute. She specializes in the foreign policy of petrostates, in particular Russia and Saudi Arabia.

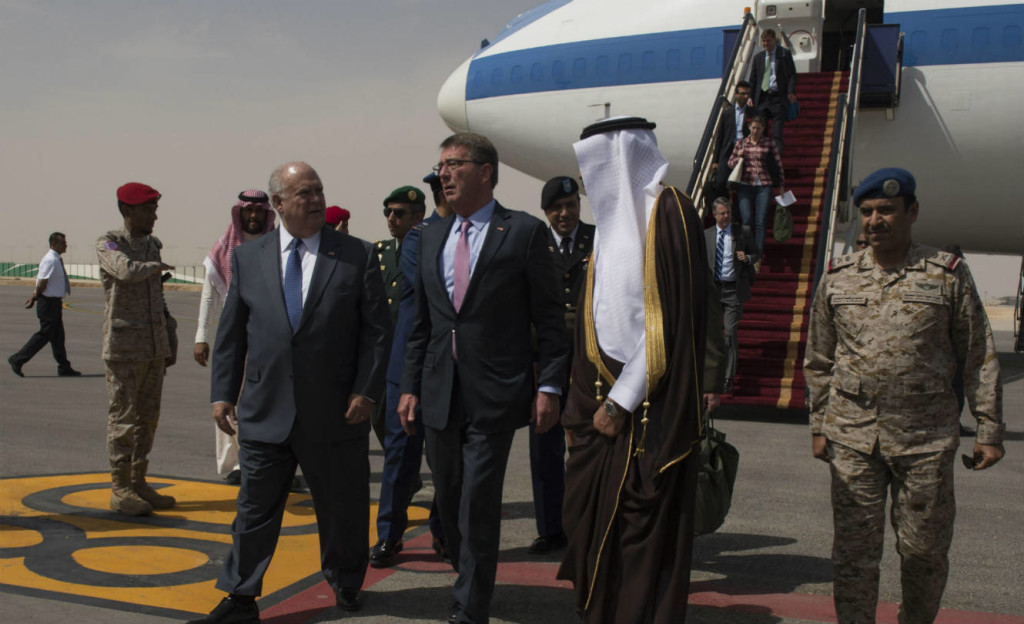

Image: Photo by Air Force Senior Master Sgt. Adrian Cadiz