Join War on the Rocks and gain access to content trusted by policymakers, military leaders, and strategic thinkers worldwide.

On June 22, the United States launched precision airstrikes as part of Operation Midnight Hammer against Iran’s nuclear facilities at Fordow, Natanz, and Isfahan. In the wake of those strikes, President Donald Trump said the operation had “totally obliterated” those facilities, while Tehran’s parliament voted to grant the government authority to close the Strait of Hormuz. Such a move, if successfully carried out, could instantaneously disrupt nearly one-fifth of the world’s oil shipments and cause substantial and potentially cascading economic harm to countries across the globe.

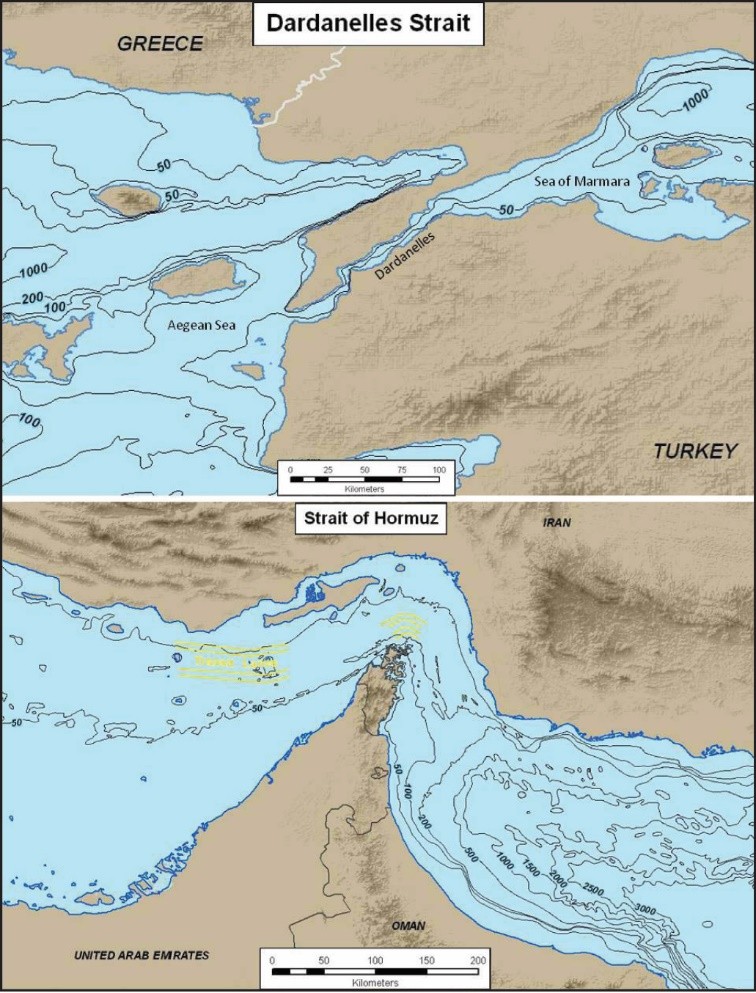

Iran threatening to close the Strait of Hormuz is not new. It has periodically issued statements to that effect and has been building capabilities to do so for several decades. In 2011, while serving as an advisor to U.S. Central Command, concern over this possibility led command leaders to ask me to conduct a comparative analysis of a potential Strait of Hormuz closure with Britain’s historic failure to reopen the Dardanelles Strait in 1915. While the two scenarios have substantial geopolitical and technological differences, both episodes center on maritime chokepoint warfare, layered and asymmetric threats, and the importance of political-military alignment and strategic communications when economic and kinetic warfare combine.

Here, I will update and summarize the lessons I previously identified for U.S. military leaders. As I stated in my paper then, “Although it may seem unlikely that a near-perfect-storm of errors and misjudgments would doom the U.S. to disaster in the [Strait of Hormuz] as it did the British at the Dardanelles, it is still better to eschew faith in the odds and apply the lessons of the past than to leave open such a possibility.”

The British Failure at the Dardanelles

By December 1914, opposing European forces were largely deadlocked along the Western Front of World War I, as the German march toward Paris had been halted and massive armies stood trench-to-trench, each side daring the other to attempt a charge in the face of withering machine gun fire. By this time, Britain and France had lost more than a million men, casualties that seem unfathomable by today’s standards but were hardly the final toll of the war.

In early 1915, British leaders — including the First Lord of the Admiralty, Winston Churchill — conceived of a plan to break this stalemate by opening a new front against the Ottoman Empire. The Dardanelles Strait, a two-to-four-mile-wide waterway linking the Aegean Sea to the Sea of Marmara, was a strategically vital economic and military chokepoint. Seizing it, London believed, would allow Allied navies to threaten Constantinople, force the Ottomans out of the war, and open a key supply route to Russia, which was increasingly isolated and under strain on the Eastern Front.

The Turkish defenses at the Dardanelles were constructed in three layers. The entrance was guarded by four old forts, containing a total of 16 heavy and seven medium-range guns. Past the entrance, the second layer of defense consisted of numerous permanent batteries of six-inch guns. Following an ill-advised preliminary shelling of the forts by British ships in November 1914, this second layer was fortified with mobile six-inch howitzer batteries of four guns each along with numerous searchlights. At the aptly named “narrows” was the third layer of defense, consisting of 324 sea mines and two huge ancient fortresses armed with 72 guns of various calibers. Thus, the Ottomans had in place a complex, integrated defense: The mines would block passage of the strait; the mobile howitzers would prevent sweeping of the mines; and the larger guns of the forts would protect the howitzers by keeping Allied ships at bay.

The Dardanelles campaign began in February 1915 with a naval-only strategy. British and French battleships bombarded Ottoman coastal defenses, intending to suppress artillery batteries while trawlers manned first by fisherman and later by British Navy volunteers cleared the heavily mined waters of the strait. Allied bombardments, however, proved ineffective, as the Ottoman guns were well-camouflaged, dispersed, and able to quickly recover or redeploy. Minesweeping operations were hampered by poor intelligence and visibility, enemy observation and fire, and wildly differing views of acceptable losses by senior leaders and the men manning the boats. The Allies underestimated the extent and effectiveness of the Ottoman minefields, assuming that dominance of the sea alone could force a breakthrough. After several unsuccessful attempts, on March 18 the Allies mounted a major push to drive through the strait. While the initial bombardments appeared successful this time, a line of undetected mines laid just days earlier by Ottoman defenders who had studied the Allies’ tactics sunk three battleships and damaged three more in a single day. The loss of these ships and many of the men aboard them shocked Allied leaders and led them to abandon the naval-only approach.

To avoid loss of prestige from this debacle, the British government authorized a land invasion to seize the Gallipoli peninsula and neutralize the shore defenses controlling the strait. Beginning on April 25, British troops, along with cadres from Australia and New Zealand, landed at multiple beaches. The landings were poorly coordinated, met with stiff resistance, and quickly bogged down into brutal trench warfare. The Gallipoli campaign dragged on for nine more months in appalling conditions, with mounting casualties, logistical failures, and no breakthrough. Inter-service rivalry, indecisive leadership, and shifting political direction compounded the stalemate. Ultimately, the Allies withdrew in early 1916, having suffered more than 250,000 casualties with no strategic gains. The Dardanelles and Gallipoli campaigns became symbols of military overreach and strategic failure, shaping British civil-military relations and operational planning for years to come.

Image: A Strait Comparison: Lessons Learned from the 1915 Dardanelles Campaign in the Context of a Strait of Hormuz Closure Event (CNA, 2011).

Image: A Strait Comparison: Lessons Learned from the 1915 Dardanelles Campaign in the Context of a Strait of Hormuz Closure Event (CNA, 2011).Iran and the Strait of Hormuz

The Strait of Hormuz is universally considered one of the key economic maritime chokepoints in the world, largely due to the amount of oil that flows through it and the geopolitical tensions that surround it. The strait, which separates the Gulf of Oman to the east from the Persian Gulf to the west, is approximately 170 miles long and 35 miles wide at its narrowest point. Water depth in the strait varies from 130 to 660 feet, with an average depth of about 160 feet. The internationally accepted transit lanes through the strait consist of two-mile-wide channels for inbound and outbound traffic, with a two-mile-wide buffer zone in between. The water in these channels is less than 160 feet deep.

To bolster the credibility of its threat to this strategic chokepoint, Iran has been developing applicable military capabilities for many years. These capabilities include conventional ones such as navy ships (e.g., corvettes, drone carriers), submarines, torpedoes, and various anti-ship drones and missiles, as well as asymmetric capabilities, such as missile- and explosive-laden fast attack boats, sea mines, and unmanned underwater vessels. In the same way that the Ottomans employed a layered defense in the Dardanelles, Iran would likely use mines as the centerpiece of its approach to closing the Strait of Hormuz, with overlapping layers of threat coverage from its other capabilities.

The question of whether Iran would ever actually use these capabilities to close the strait and the extent to which it might be successful in doing so has been debated for over a decade. Among the vectors that have shaped the debate are the extent to which Iran’s leadership would feel strategically cornered enough to sacrifice its own economic and political interests to inflict global economic harm, the degree to which the United States could detect impending actions to close the strait and act pre-emptively to stop them, and the effectiveness of U.S. capabilities to re-open the strait if its intelligence fails to provide adequate indications and warning.

Listen to this episode of The Insider featuring author Jonathan Schroden by becoming a War on the Rocks member here

Applying Lessons from the Dardanelles

There are notable geographic and technological differences between the two scenarios that render most tactical comparisons of little contemporary help. But Britain’s failure at the Dardanelles was so spectacular because its shortcomings transcended tactical errors into the operational and strategic realms. There are, therefore, at least four applicable lessons for a Strait of Hormuz scenario.

Mine Warfare and the Modern Asymmetric Threat

One of the key reasons the British naval assault on the Dardanelles failed was the unexpected effectiveness of Ottoman minefields. Despite achieving initial success in suppressing coastal artillery, the Allies lost several warships to mines in a single day, halting the campaign’s momentum and forcing a costly pivot to land operations at Gallipoli.

In a Strait of Hormuz crisis, the United States would likely face a similar threat: naval mines and other asymmetric sea denial systems. Iran has a sizable inventory of sea mines, some capable of being delivered by submarines or disguised commercial vessels. While mines can be cleared and the U.S. Navy has four dedicated mine countermeasures ships stationed in Bahrain, the service has a generally strong distaste for the mine-clearing mission and has commensurately under-resourced and under-maintained these ships for many years. As such, they would likely only be effective in an environment free of non-mine threats, which is the exact opposite of what Iran would seek to establish in and around the Strait of Hormuz as part of a closure operation. Clearing mines from its shipping channels would take time, put U.S. sailors at risk, and require capabilities that are scarce and slow to deploy.

The British misjudged the threat of mines at the Dardanelles, and it is possible the United States could do the same in the Strait of Hormuz. If a closure event happened in the near term, the U.S. Navy might discover that its mine-clearing capabilities are too little, too late.

Strategic Overreach and the Danger of Wishful Thinking

The Dardanelles campaign began with high hopes and vague objectives — the historical analog of today’s “strategy by vibes.” British and French leaders believed they could force open the strait with naval power alone, destabilize the Ottoman Empire, and perhaps even bring it to surrender. What followed was a series of operational missteps rooted in faulty assumptions and a deep disconnect between political aims and military means.

The lesson for U.S. leaders is to recognize the risk of similar overreach in the context of a Strait of Hormuz conflict. While the operational goal — reopening or keeping open a vital maritime chokepoint — may appear straightforward, the political objectives surrounding such an action could quickly become overwhelming. To what extent, for example, would the United States need or want to degrade Iran’s capabilities to enable mine-clearing operations? If a U.S. Navy mine countermeasures ship was struck by Iran, how much further would the United States be willing to escalate? Would reopening the strait be sufficient, or would the United States feel compelled to “teach Iran a lesson”? Would calls for regime change gain traction if the conflict persists? And would U.S. allies and partners support these actions, oppose them, or push Washington along? The answers to these questions would logically determine the scale and nature of the military response, yet such inquiries often go unarticulated until operations are underway. In the absence of political clarity, operational actions could escalate into a broader regional war without clear purpose or attainable goals — precisely the path that doomed the British effort in 1915.

Dominating the Narrative

The Dardanelles campaign was also a failure of strategic communication. British leaders initially oversold the ease of the operation, then struggled to manage public expectations as the campaign stalled. A lack of transparency and inconsistent messaging undermined public support and complicated diplomatic efforts with allies and neutral states.

Iran has repeatedly demonstrated its skill in shaping favorable narratives, portraying itself as the victim of Western aggression and using regional media to stoke anti-American sentiment. The United States, conversely, tends to view strategic communications as an afterthought to kinetic action. If the U.S. military was compelled to respond to Iranian actions in the strait, it would do well to anticipate the Iranian state information campaign that would inevitably follow. Countering that campaign — or better yet, seizing the information initiative — would require prior planning, coordination across government agencies, and the empowerment of communicators at all levels. A Strait of Hormuz crisis would be as much a battle of narratives as a military engagement. History shows that winning the latter is no guarantee of success in the former.

Command Friction and the Tempo of Decision

The final lesson from the Dardanelles is perhaps the most institutional. The British campaign was plagued by indecision, unclear command relationships, and a painfully slow operational tempo. Senior military leaders lacked unity of effort, and political authorities wavered between alternative courses of action. The result was a muddled campaign that squandered initiative and compounded losses.

As has played out over the past few weeks, a crisis in the Strait of Hormuz would likely unfold in a time-compressed and politically charged environment. It is a geopolitical powder keg where an incident could escalate within hours. In such a context, command clarity and decision speed are essential. The U.S. military would need preplanned concepts of operation, well defined rules of engagement, and a rapid feedback loop between operational commanders and national-level decision-makers in Washington. Coordination with regional partners — some of whom may be hesitant or divided — would also be critical.

Avoiding the kind of command friction that hobbled the Dardanelles campaign would require not only well-defined command structures, but also shared expectations about decision timelines, escalation thresholds, and delegated authorities. In this environment, hesitation could be fatal — to forces, to credibility, and to deterrence.

Conclusion

The story of the Dardanelles is a cautionary tale about the consequences of mismatched ends and means, underappreciated asymmetric threats, incoherent messaging, and sluggish decision-making. These are not novel observations; if they ring close to home, it is because the U.S. military exhibited the same pathologies in its wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. It is not a stretch to worry about their recurrence in a future crisis.

The Strait of Hormuz may look very different from the Dardanelles on a map, but from a strategic and operational standpoint, they rhyme in ways that demand attention. The British failure at the Dardanelles was not inevitable. Rather, it was an institutional failure to align strategy, capacity, and narrative. Today, if the Strait of Hormuz were to be contested, the same dynamics would be in play — but with exponentially higher stakes and speed.

Under Trump’s orders, the United States struck aggressively at Iran’s nuclear infrastructure. Iran responded with closure threats and missile attacks. What comes next is not inevitable, but it will be shaped by whether we can avoid the mistakes of history’s tragedies. Lessons from the Dardanelles can help ensure that today’s strategic chokepoint doesn’t become tomorrow’s strategic catastrophe.

Jonathan Schroden, Ph.D., is the chief research officer at the CNA Corporation, a not-for-profit, nonpartisan research and analysis organization based in Arlington, Virginia. He is also a non-resident senior fellow with the University of South Florida’s Global and National Security Institute. You can find him at www.linkedin.com/in/jonathanschroden and @jjschroden.bsky.social.

The views expressed here are his and do not necessarily represent those of the CNA Corporation, the University of South Florida, the Department of the Navy, or the Department of Defense.

Image: Diyarbakırlı Tahsin Bey via Wikimedia Commons