How to Protect Europe From Risky Foreign Direct Investment

Last September, Italian police raided the offices of an aeronautics firm called Alpi Aviation that provided drones to the country’s military. Alpi stood accused of violating the Golden Power, an Italian law intended to prevent the unregulated foreign acquisition of defense companies. In addition to sending a military drone to China marked as a “model aircraft,” Alpi allegedly failed to notify the government of its opaque 2018 sale to a Chinese enterprise linked to China Railway Rolling Stock.

The Alpi Aviation case has prompted renewed debate over the European Union’s foreign direct investment screening mechanism, which was implemented in 2020 and will be up for evaluation by 2023. There are several challenges to current European efforts to screen foreign investments: not all member states have national screening mechanisms; member states that do have screening mechanisms have uncoordinated approaches to information collection and regulation; and member states can ignore E.U. advice on how to manage potentially problematic investments.

Even this imperfect arrangement has brought tangible benefits. There is now a growing awareness of the potential risks posed by unregulated foreign direct investment. A growing number of member states are adopting screening mechanisms and the European Commission now has a better overview of inbound investments. However, unless the system is improved, there is every reason to think that mistakes like the sale of Alpi Aviation could happen again.

A few simple steps would help to improve the European Union’s ability to monitor and stop potentially risky foreign direct investment. First, Brussels should push all member states to adopt uniform methods for screening investments. Second, member states should do more to screen transactions themselves, since ultimately only they can block problematic investments. Third, the European Union should begin a conversation about how to regulate joint ventures and outbound investment. Finally, to avoid overburdening the European Commission with unnecessary notifications from member states, the European Union should and provide clearer guidelines to member states on which foreign transactions need screening.

Upgrading the E.U. Framework for Foreign Direct Investment Screening

If the European Union wants to have a clear idea of what is going on within its borders and stop potentially risky acquisitions, it needs a better foreign direct investment screening mechanism. In its current configuration, the E.U. framework requires member states that possess their own screening mechanism to notify the European Commission when they examine an investment. Then, the European Commission assesses those notifications and further screens flagged investments that it believes might pose a risk to the E.U. security and public order. Afterwards, the commission, along with any other member states who wish to, provide the member state with advice on how to proceed. Ultimately, the member state can either take or ignore the commission’s advice.

A E.U.-wide effort to screen investments is a challenge, first and foremost, because not all member states have national screening mechanisms. Nine member states out of 27 still do not have any. And three (Bulgaria, Croatia, and Cyprus) do not even have plans to adopt one. Amongst the 18 who do, there are immense discrepancies. For example, E.U. members with screening mechanisms do not always target the same sectors or have dedicated bodies for investment screening. Total coherence is always a mirage in the European Union, but this level of incoherence places European security under unnecessary risk. Foreign enterprises can enter the single market via European countries that either do not have screening mechanisms or have very lax forms, and then compose a net of ownership that will make it incredibly difficult to identify them as foreign enterprises. Luxembourg is well known for the proliferation of such “Europeanization” practices thanks to the numerous Chinese banks in the country.

Brussels has two ways of learning about potentially risky investments in the nine countries with no screening mechanism: if a transaction attracts media attention and by looking at the quarterly reports on inbound investments in Europe provided by a private contractor that detail investment transactions. However, even if the European Union and other member states were to advise the blocking of a deal, countries without a regulatory mechanism would lack the legal tools to do so. In other words, without a national regulation in place that allows a member state to block an investment, the European framework is of little use. Hence, the need for all 27 member states to adopt better regulatory policies.

Ideally, member states would conduct systematic mapping of inbound investment on an ongoing, rather than quarterly, basis. Since member states are the ones who can block investments, that would facilitate the process of screening. At the moment, even countries with screening mechanisms depend upon companies notifying the screening body of the acquisition. If notification does not happen, national screening bodies have little capacity to know of the existence of that acquisition. And as the case of Alpi Aviation shows, notification does not always occur, allowing for a small but potentially problematic number of acquisitions to go unnoticed. In 2018, the Italian body tasked with reviewing investments was not aware of Alpi’s sale because the company did not report it. Despite Italy already possessing a screening mechanism to regulate inbound investments, the country did not actually make a concerted effort to map it. The acquisition came to surface by chance during an investigation of potential Iran sanctions violations. This suggests that many other acquisitions may have occurred without the screening body being aware of them.

Thankfully the European Commission now receives regular reports on inbound investments into the European Union. The commission may share the information with E.U. capitals after it receives the data, but the process would be more efficient if member states also mapped investments themselves without necessarily having to wait for the commission report. After all, if member states remain the only ones who can block potentially problematic foreign direct investment, more complete and timely information would be better.

Proposal for Short-Term Improvements

Not all is lost. According to the European regulation for screening investments, the European Commission or any member state can provide their opinion on an acquisition, even if it has not been notified. To do so, however, the European Commission needs to be aware of such an acquisition. If the enterprise does not notify the member state of the transaction, or if a member state does not notify Brussels, Brussels has two options. First, to use the information from the reports to raise a case with a member state. Second, to incentivize member states who have a screening mechanism to themselves map inbound investments in order to have a comprehensive view of what is happening within their borders.

The risks are not limited to new acquisitions, but also to already concluded transactions. In the absence of a proactive and costly effort to map out national situations, it will not be possible to know the extant degree of technological transfer and, hence, the level of risk. Surely not all sectors and enterprises are sensitive, not all acquisitions lead to technological transfer, and not all technological transfers present an issue of national security. However, a clear picture of the status of foreign direct investment in each member state could improve the implementation of necessary restrictions, while safeguarding an open environment for other investments.

Outbound foreign direct investment is also a blind spot for Brussels, as well as joint ventures between European and Chinese enterprises that develop technology potentially threatening national security. Although both controversial, the European Union should have a debate about the adoption of a screening mechanism that includes joint ventures and outbound investment. The inclusion of these two additional aspects should be treated with caution and should a policy be proposed, it should be limited to a scope that protects security.

Luckily, protecting the European Union from risky inbound investment does not require a drastic revision of the existing E.U. regulation. There is little support for centralizing screening and blocking power in the hands of the European Commission. The “easier” solution, however, requires money, and specifically the allocation of funds at the member state level. This means that it requires political support. There have already been complaints over a lack of resources to apply the existing European regulation at the national level, and Brussels lamented the reception of numerous notifications that did not amount to risky investments, unnecessarily increasing the amount of work for the commission. After the first year of the screening mechanism being active, the commission could share more precise guidelines on which transactions require notification. By doing so, it could mitigate the problem posed by excessive and irrelevant notifications.

The case of Alpi Aviation is unlikely to be the only case of an acquisition of sensitive technology that slipped under the radar before or after the current E.U. screening mechanism became operative. What the European Union needs is a better and clearer picture of existing and emerging acquisitions in the region, and this means that member states should step up their game.

How can this be achieved? The first step is for all member states to adopt a screening mechanism. The second would be more funding and staff for member states to map out existing and emerging investments. The European Union should keep pushing for more commitment from member states to map and screen inbound foreign direct investment, as these states are the ones who can block potentially risky investments. The European Union should provide more detailed guidelines so member states only forward risky transactions to Brussels rather than simply sending notifications for all of them. Third, the commission should incentivize the adoption of the same method of screening and reporting by all member states. In this way, both member states and Brussels can become aware of transactions that have not been notified and trigger the relevant national and regional screening mechanisms. The commission would still have a limited ability to influence a member state’s decision over specific investments. But once these potentially risky investments were identified and publicized, media attention and peer pressure could work wonders.

Francesca Ghiretti is an analyst at the Mercator Institute for China Studies (MERICS) where she covers European Union-China relations with a focus on economic security and China’s global investments. She is finishing a Ph.D. from King’s College London, War Studies, where she is a Leverhulme fellow at the Centre for Grand Strategy.

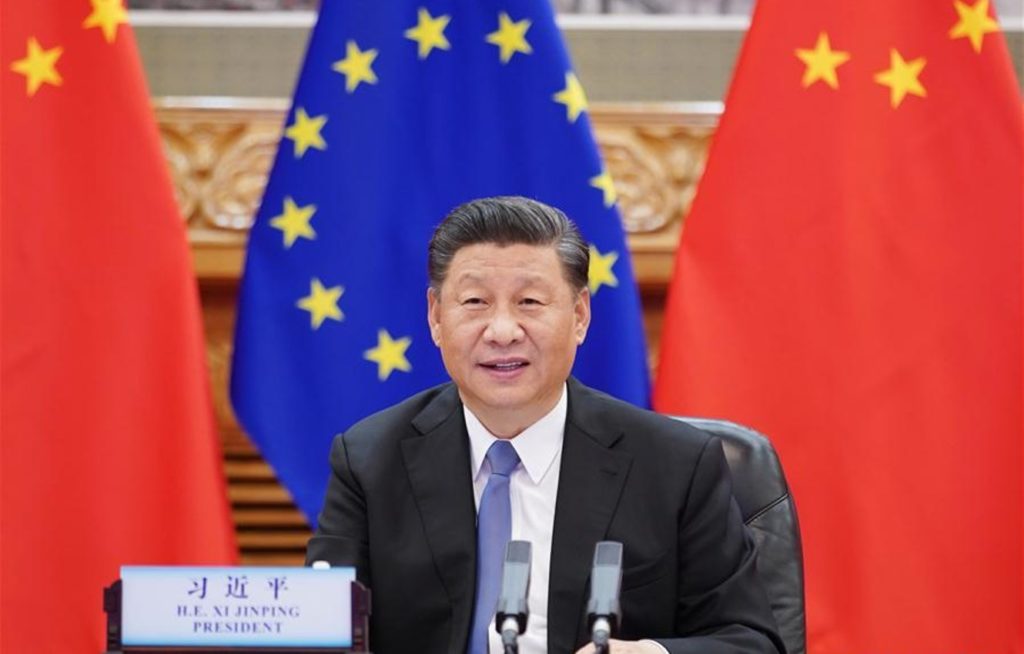

Image: Xinhua (Photo by Wang Ye)