Join War on the Rocks and gain access to content trusted by policymakers, military leaders, and strategic thinkers worldwide.

According to Article II of the U.S. Constitution, there are only three criteria for being president: be a natural born citizen of the United States, be at least 35 years old, and have been a resident of the United States for 14 years. While the Constitution states that the president shall be commander-in-chief of the Army and Navy, the position has no pre-qualifications. Nevertheless, the role of commander-in-chief is often invoked in speeches, at debates, and in political advertisements. But what makes a person qualified for this role? One measure of qualification — but certainly not the only one — is past military service. This should not weigh more than any other factor, if at all, but it nevertheless is relevant given that presidential candidates — especially nominees in the final months of the election — will need to find some way to prove their ability to command one of the world’s largest militaries.

It is important to note here that simply having had some military experience is not necessarily beneficial either to becoming president or during one’s presidency. It is the same reason that a resume alone does not guarantee a successful presidency. For example, few individuals had more breadth and depth in their professional backgrounds than James Buchanan. Arguably one of the most qualified individuals to become president, Buchanan was one of the worst. Nor is all military service equal.

Voters, especially veterans, may distinguish between candidates who served in combat (such as John F. Kennedy) and those who did not (Richard Nixon). But the issue also may be disregarded completely in favor of more divisive domestic issues, such as happened in the 2004 race between George W. Bush and John Kerry. In short, voting behavior can be complicated.

This article is a simple, non-academic representation of a history of presidential military service. It neither breaks new ground nor proposes recommendations based on lengthy analysis. For authoritative academic work on this topic, consult the work of Peter Feaver at Duke University and others. Instead, the graphs below offer a window into American presidents’ military service. They also suggest possible ramifications for the 2020 election and beyond because fewer presidents in the past thirty years have served in the military and, those that did were junior in rank. For example, do voters care about military service in their candidates? Why were most of the post-World War II presidents those with Navy experience, especially as junior officers, when the Navy was only about a third of the size of the Army during the war years? And why have only generals been president but no Navy admirals?

With regard to the last question, part of the answer lies in the fact that the nation had no rank of admiral until 1862. A few prominent admirals emerged from the Civil War, such as David Farragut and his step-brother David Dixon Porter. However, they were overshadowed by generals who garnered attention from the press and the public. Similarly, the Navy has always received minimal attention for its role in the Anaconda Plan, compared to the Army, which was engaged in the largest battles and suffered heavy casualties that affected so many communities throughout the country. Only one American war — the Spanish-American War — produced a political figure from the Navy and that was Adm. George Dewey. This was, in part, because it was a naval conflict punctuated with images of a sunken U.S. warship and news of two major victories at sea. Nevertheless, the land campaign still produced heroes out of Theodore Roosevelt and Leonard Wood, the former becoming vice-president and later president, and, the latter becoming a candidate for the presidential nomination. Likewise, no U.S. admiral from World War I could capture the public’s attention. And, despite the role of Admirals Chester Nimitz, William Halsey, Raymond Spruance, Ernest King, and others during World War II, the campaigns of generals simply overshadowed naval leadership.

Presidential Military Service: An Overview

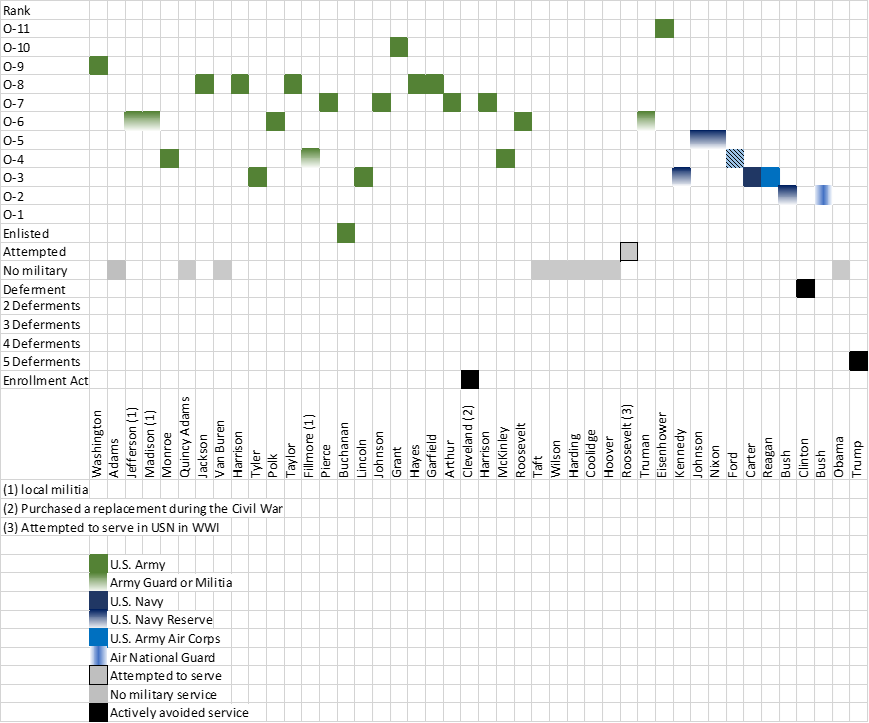

In the chart below, I have categorized the U.S. presidents by their military branch, the highest rank they achieved while living, whether they had no record of service, and whether they actively avoided military service. Thirty-one of the 44 presidents (Grover Cleveland is counted here only once despite having had two nonsequential terms) had some form of military service ranging from enlisted to five-star general. Of those, 12 — more than 25 percent — reached the rank of general in the Army. Only one, Dwight Eisenhower, served in the 20th century. Nine had no military service, one (Franklin Roosevelt) attempted but failed to serve in the Navy, and three actively avoided military service either via the Civil War Enrollment Act, through which an individual could hire a substitute, or through military deferments.

Source: Generated by the author.

Service during the 20th century led to two Army officers (Truman and Eisenhower) becoming president, while Navy officers comprise the majority of presidents who served. Theodore Roosevelt served during the Spanish-American War but was elected in the 20th century. Yet, no senior Navy officer, namely flag officers, became president. In fact, very few presidential candidates have been senior officers in the Navy. The most senior naval officer who was a nominee was John McCain, who retired from the Navy as a captain in 1981.

What emerges are three distinct periods or groups of presidents with varying degrees of military service.

Group 1: The 19th-Century Generals

Source: Generated by the author.

During the 19th century, 21 of the 25 men to serve as president had military service. (Theodore Roosevelt is included in this group as he was elected as vice president in 1900.) More than half were generals, primarily during the Civil War. Only two flag officers explored running for office to different degrees. Commodore Charles Stewart (there were no admirals until 1862), was approached by Pennsylvania merchants to seek the Democratic nomination in 1844 with the proposal that James Knox Polk serve as his running mate. Stewart balked but managed to receive one vote during the first two ballots of the convention. In 1900, fresh from his victory at the Battle of Manila Bay during the Spanish-American War, Dewey was encouraged to run for the Democratic nomination. But he proved a poor campaigner, making gaffes about the role of the president and facing opposition from Protestant voters for having married a Catholic. He later endorsed Republican William McKinley.

Group 2: The Early 20th Century and Silent Service

Source: Generated by the author.

During the longest period of military service absence (William Taft to Franklin Roosevelt), only one military officer had the stature and popularity to run for president. Gen. John “Black Jack” Pershing commanded the American Expeditionary Force during World War I and was recognized with “General of the Armies” upon his return, but he did not receive support from the troops he had commanded. Aside from World War I, this group of presidents would have had little chance to serve, except for in the Spanish-American War. However, given the limited scope and brevity of that war, there simply weren’t as many opportunities to serve as with more expansive conflicts.

Group 3: The Post-War Decline of Rank and Service

Source: Generated by the author.

Dwight Eisenhower’s leadership of Allied forces in Europe propelled him to the presidency in 1952 but another equally-known figure from World War II might have preceded him. Gen. Douglas MacArthur held aspirations for running in 1944 and 1948, according to William Manchester’s biography of MacArthur, “American Caesar.” In 1952, Sen. Robert Taft — then competing with Eisenhower for the Republican nomination — considered MacArthur as his running mate.

Beginning in 1960, World War II Navy veterans — mostly junior officers — dominated the presidency. Kennedy, Lyndon B. Johnson, Nixon, Gerald R. Ford, and George H.W. Bush were all Navy Reserve officers during the war. The sole active duty Navy veteran to become president was Naval Academy graduate Jimmy Carter. Ronald Reagan was the only other Army veteran of World War II, having served in the Army Air Corps. The Navy, thus, had an unusually disproportionate number of presidents who served during World War II given that the Army was approximately three times the size of the Navy for any year during the war.

This period also included presidents who had deferments from military service, in both cases with regard to the Vietnam War.

The VPs

Source: Generated by the author.

Presidents’ running mates offer another glimpse into high profile politics and military service. Most vice-presidents had no service and, in recent years, two of them had five deferments, each from the Vietnam War.

Falling Off the Service Cliff

Source: Generated by the author.

Since 1992, the election of presidents and vice presidents with military deferments or no service at all has become normalized. This trend will continue if some of the current poll leaders for the Democratic nomination win the general election, such as Joseph Biden, who had five deferments, and Bernie Sanders, who applied for conscientious objector status during Vietnam. Another leading contender, Pete Buttigieg, would continue the trend of junior Navy officers being elected, specifically from the Navy Reserve. Tulsi Gabbard is a major in the Army National Guard, but has been polling in the single digits, while retired Rear Adm. Joe Sestak also polled poorly before ending his campaign.

The Service Gap and the Validation Surge

Source: Generated by the author.

This service gap — a series of presidents and vice presidents with no military service or active avoidance of service — may be a temporary phenomenon. Just as Bob Dole was the last World War II veteran to run for president, it is currently only septuagenarian males who could request military deferments during the Vietnam War when there was a draft. In the all-volunteer force, the issue of a service gap due to active avoidance becomes irrelevant.

One factor in this service gap that might endure is what I’m calling a validation surge — a new era of retired flag and general officers endorsing candidates. The modern phenomenon of high profile, senior endorsements came into its own during the 1992 election, but was foreshadowed by retired Marine Corps Gen. Paul X. Kelley’s endorsement of H.W. Bush in 1988. Four years later, retired Adm. William Crowe endorsed Bill Clinton. Endorsements proliferated with each election to the point where Donald Trump and Hillary Clinton were boasting about how many military endorsements each had received during the 2016 election. This is not a new issue. In 2012, the Center for a New American Security published its report, “Military Campaigns: Veterans’ Endorsements and Presidential Elections,” in which the authors (including Feaver) stated: “competition for these endorsements has intensified, with each campaign seeking to best the numbers and ranks put out by the other side in the last election … Candidates who lack a military service record — or perhaps have one that could use burnishing — have often sought endorsements from groups that speak on behalf of veterans.”

As American voters enter the 2020 election, this report is worth revisiting, as are other warnings, including Kori Schake’s that endorsements by retired general and flag officers erode public trust in the military, encourage the military to see itself as a political actor, and make it harder for active-duty military leaders to do their jobs.

Claude Berube, PhD, is a contributing editor at War on the Rocks. He has taught in the political science and history departments at the United States Naval Academy. His third book (co-authored with Steve Frantzich) was titled, Congress: Games and Strategies. The views expressed here are not those of the Navy or the Naval Academy. Twitter @cgberube.

CORRECTION: A previous version of this article stated that only one Army officer became president in the 20th century. That was incorrect. The article has been corrected to reflect President Theodore Roosevelt and President Harry Truman’s military service, which were in the original charts. In addition, a previous version also stated, “Nevertheless, the land campaign still produced heroes out of Theodore Roosevelt and Leonard Wood, the latter becoming vice-president and later president, and, the former becoming a candidate for the presidential nomination.” This was a mistake. The former become vice-president and later president, while the latter only became a candidate for the presidential nomination.