Join War on the Rocks and gain access to content trusted by policymakers, military leaders, and strategic thinkers worldwide.

The Trump administration wants to make it more expensive for American allies to host U.S. military personnel in their country. It reportedly intends to ask allies to drastically increase the amount they pay for hosting U.S. forces, sparking new fears that the United States will eventually withdraw from these countries entirely. Under the so-called “cost plus 50” proposal, allies would pay for the full cost of hosting U.S. units, plus a 50 percent premium. Germany and Japan will walk the plank first.

Numerous analysts have explained how demanding “cost plus 50” will irreparably harm core alliances and damage U.S. national security in the long term. Replacing the value of U.S. forward basing with U.S.-based military capabilities would almost certainly be so expensive and complicated that it would make execution of the National Defense Strategy impossible, thereby necessitating a wholesale change in American security policy. It’s worth examining what exactly “cost plus 50” would cost the allies who host and pay for U.S. forces. Moreover, should negotiations fail and lead to withdrawal of those forces and closure of those overseas bases, what would it cost the United States?

In the most benign scenario, “cost plus 50” would double Japan and South Korea’s payments for U.S. forces and quadruple the contribution from Germany, with much larger increases if military pay is included in the calculations (a 926 percent jump for Germany). Withdrawal of U.S. forces from these countries would certainly cost the United States itself several billion dollars upfront, with the likely immediate bill rising into the tens of billions of dollars to provide new basing, housing, and training ranges for American forces at home.

Can Allies Afford ‘Cost Plus 50’?

In June 2018, the Pentagon began an analysis of U.S. basing in Germany after President Donald Trump expressed interest in withdrawing U.S. forces there. That furor died down, but it wasn’t long before the same story played out on the Korean peninsula. Seoul and Washington began negotiating earlier this year over cost-sharing for U.S. troops. Trump first formulated his “cost plus 50” proposal as he publicly flirted with the idea of withdrawing all U.S. forces from South Korea. While the two sides agreed on South Korea paying slightly more to host U.S. troops, the deal only lasts for one year rather than the usual five, so new talks must begin soon. Similarly, talks on the next Japanese cost-sharing agreement will start later this year.

The “cost plus 50” plan calls into question long-term U.S. military presence in Germany, Japan, South Korea, and elsewhere. What would it cost American allies to meet the new threshold? The Pentagon pegged the cost for overseas presence in 2019 at about $21 billion, including military pay, operations spending, and military construction. Of that total, $15 billion stems from American bases in Germany, Japan, and South Korea, who together cover about $4 billion of the costs.

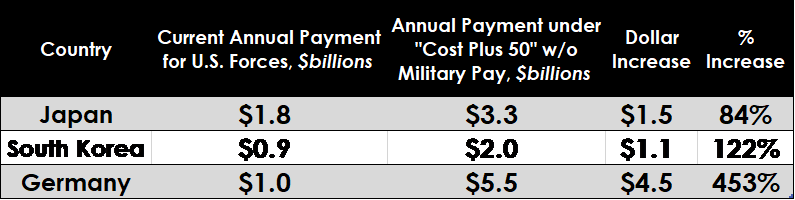

Under “cost plus 50,” those payments would skyrocket — how far depends on whether the calculations include the salaries of these troops. Normally, previous cost-sharing negotiations excluded the cost of U.S. military salaries, since the United States would presumably retain the services of those personnel, no matter where they’re stationed. Under this interpretation, allied contributions would increase as follows:

Source: Author’s calculations. Current annual payments from RAND (Germany), Congressional Research Service (Japan), public reporting (South Korea). Current overseas presence cost based on Department of Defense data.

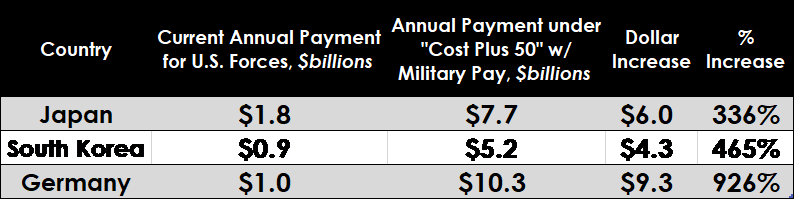

If U.S. military pay is counted, the allied contributions would increase as follows:

Source: Author’s calculations. Current annual payments from RAND (Germany), Congressional Research Service (Japan), public reporting (South Korea). Current overseas presence cost based on Department of Defense data.

In either scenario, allies would pay much more to continue hosting U.S. troops. Consider that in very aggressive negotiations, the United States was only able to increase the South Korean contribution by about $70 million, less than 10 percent above the current cost-sharing agreements. The Obama administration negotiated a similar increase in 2014. Clearly, “cost plus 50” would be a fundamental change in burden-sharing negotiations. Such a change could engender responses from allies and/or failures of negotiations that make a full withdrawal of U.S. forces more likely — an option Trump has frequently discussed with interest.

Costs of Withdrawal

Trump’s maximalist negotiating position raises the specter of U.S. withdrawal from key overseas bases. Closing up shop in either Europe or East Asia would cost the United States billions up front and could easily cost more than $10 billion over the first few years, with the potential for significant recurring costs for environmental remediation thereafter. The United States would forsake decades of construction investments in these places, including $5.8 billion in Germany and $2.4 billion in Japan over the past two decades. While there are certain ways in which overseas troops are more expensive, these differences are offset, to differing degrees, by allied contributions. Yet any annual savings at the margin would be dwarfed by the upfront costs of closing bases and building new ones in the United States. Withdrawal would also require new investments in U.S.-based forces and logistics chains to replace the power projection capabilities of forward-based American forces. On balance, withdrawal from U.S. overseas basing would likely impose significant costs on the United States, immediately and over the long term.

Summing up the new investments needed to replace the power projection capability that U.S. forces abroad provide is a massive task, beyond the scope of this article. Here I focus on what it would immediately cost to pull U.S. troops out of major overseas bases. Data from a 2004 Congressional Budget Office study and a 2013 RAND report makes possible a rough back-of-the-envelope calculation. The United States stations about 75,000 military personnel in Japan and South Korea and a little more than half that number in Germany and Italy. For the purposes of this analysis, the 75,000 personnel in Japan and South Korea will serve as a yardstick, so cut all the bills in half for Germany and Italy.

First, simply paying to transport 75,000 personnel back to the United States costs roughly $500 million, excluding the bill for bringing all their equipment back. As seen in Afghanistan , the cost of returning equipment normally runs in the billions of dollars. RAND estimated that shutting down bases, issuing worker severance packages, and terminating existing contracts and leases for a portion of U.S. infrastructure in Europe would cost $410 million. Thus, a more expansive close-out could run up the tab to $1 to 2 billion. That does not include the very real potential for long-term environmental remediation work and preparations for redevelopment by private industry, which normally occur following base closures. Both types of expenditures routinely occur in domestic base closures.

But by far the largest upfront cost to bring U.S. military units home is new construction once they get back on American soil. Where do you put 75,000 new personnel, in the case of a full withdrawal? According to RAND estimates, the new military construction to host these units and their families would easily cost $8 to $10 billion. Sure, there may be some extra room at certain large installations, such as Fort Hood or Fort Bliss. Optimists might also point out that in recent advocacy for a new base closure round, the Pentagon determined that it has approximately 20 percent excess infrastructure. But there is reason to suspect this aspect of the withdrawal will be quite expensive for the U.S. government despite the presence of “excess” resources.

While the Pentagon undoubtedly does have excess facilities at its disposal, these facilities probably don’t align exactly with what would be needed to host entire new units. The Army’s analysis, for instance, found that its major training ranges had only 2 percent excess capacity, and the Air Force analysis found a similar figure. Bringing new units home would require building new training ranges, expanding existing infrastructure, or paying allies and partners abroad for their own training spaces.

Base closure skeptics, including current Senate Armed Services Committee Chairman Jim Inhofe, often caution that infrastructure currently considered “excess” might one day be needed, should the U.S. military expand in size. However, it’s an open question whether the existing excess facilities are the types necessary to accommodate such growth. Indeed, after a decade of underfunding facilities maintenance that created a $116 billion backlog, many of these facilities likely suffer from significant degradation. Finding space for new units brought home from Germany, South Korea, or Japan would be exceedingly difficult, almost certainly requiring massive new expenditures for military construction.

Conclusion

Any assessment of the strategic wisdom of “cost plus 50” must include an appreciation of the financial scale of what the United States is asking allied nations to contribute. The scale of the increase in costs is quantitatively so large that it changes the nature of the negotiations from a tough discussion about burden-sharing to a one-way extortion conversation. That change—roughly a doubling of costs for Japan and South Korea and a quadrupling for Germany—will in large part define how allied capitals react.

One of their reactions, should the Trump administration forcefully push this proposal, is eventual withdrawal of U.S. forces. Owing to that very real possibility, evaluating the president’s “cost plus 50” position also requires factoring in the likely budgetary effects of those withdrawals here at home. The current U.S. overseas basing posture essentially pays for itself. Withdrawing U.S. forces from major bases would definitely cost the American taxpayer several billions of dollars and would likely end up costing tens of billions of dollars. Following that initial expenditure, the United States would be forced to either abandon fundamental tenets of its post-World War II defense strategy or spend tens of billions more on U.S.-based forces in order to remain capable of carrying out the current National Defense Strategy.

Rick Berger is a research fellow at the American Enterprise Institute, where he works on the defense budget and other defense policy issues. He previously served as professional staff on the Senate Budget Committee, where he covered defense, foreign affairs, and veterans policy.