Join War on the Rocks and gain access to content trusted by policymakers, military leaders, and strategic thinkers worldwide.

Ever since the House Armed Services Tactical Air and Land Forces subcommittee revealed its legislative language mandating the Pentagon study restarting the F-22 production line, the defense world has been abuzz with speculation, hopes, and dreams. While there seems to be consensus that truncating the original F-22 production was a bad idea, restarting production now will only make things worse.

How We Got Here

Washington, D.C. collectively possesses the memory of a goldfish. Those left to deal with the repercussions and politically motivated, short-sighted decisions often need to remind others of the original policy sin.

Former Secretary of Defense Robert Gates was most responsible for the termination of the F-22 program. His reasoning in 2008: The F-22 had no place in the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. This contention dismisses the notion that the U.S. military should prepare of wars of necessity — the ones that can literally change our way of life and destroy our nation — and focus instead on wars of choice that, while long and expensive, are not existential. The United States has not fought a war of necessity for decades. The purpose of the F-22 was to ensure the Joint force could reasonably ensure air superiority in these wars. Trying to make a connection between this and a terrorist plotting an attack from a remote cave in Afghanistan is irresponsible at best.

In mid-2008, Secretary of the Air Force Michael Wynne and Chief of Staff of the Air Force General Michael “Buzz” Moseley were fired for advocating the preservation of the F-22 program, and the newly appointed leadership sang an entirely new tune: 187 F-22s were all the Air Force would need.

The dogma of that number itself is telling, considering it is considerably lower than the original planned F-22 buy of 750 airframes and less than the 381 aircraft that Air Combat Command (ACC) studies showed would be needed to execute the National Security Strategy under a revised single-front war policy. Then-Air Combat Command commander Gen. John Corley, stated:

[T]here are no studies that demonstrate 187 F-22s are adequate to support our national defense strategy. Air Combat Command analysis, done in concert with Headquarters Air Force, shows a moderate risk force can be obtained with an F-22 fleet of approximately 250 aircraft.

One hundred eighty-seven was the convenient number of F-22s when the plugged was pulled, nothing more.

In a 2011 speech now viewed as tragically prophetic, Secretary Gates pointed out that “when it comes to predicting the nature and location of our next military engagements, since Vietnam, our record has been perfect. We have never once gotten it right, from the Mayaguez to Grenada, Panama, Somalia, the Balkans, Haiti, Kuwait, Iraq, and more—we had no idea a year before any of these missions that we would be so engaged.” In terms of the Pentagon’s failure to predict the next challenge, you can now add the Russian wars of aggression in Ukraine and Syria to that list, as well as the proliferation of potent Russian air defense systems to China and Iran in the past few years.

The pilot adage of “plan the flight; fly the plan” should serve as a historical reminder of why a vetted strategy to meet national security objectives even exists. Now, more than ever, the F-22 provides a stark reminder that acquisitions should be supported by a strategy-driven budget, not a budget-driven strategy. Make no mistake: The U.S. Air Force needed 381 F-22 Raptors, and it needed them yesterday. But the Air Force didn’t get what it wanted or needed, which required money be poured into other programs to bridge the capability gap. Alas, 187 F-22s are all that were built, and all that should be built. Here’s why.

Do Not Revive

While the scars of the F-22 battle remain on the force, reviving production of the F-22 will not help the Air Force with its current challenges. Ignoring the nearly insurmountable effort to find the missing tooling, and somehow finding the money to pay for it, the entire premise of building an obsolete aircraft using an equally obsolete acquisitions process is simply not viable.

The F-22 is based off 1980s requirements, built with 1990s technology, and designed to counter dated threats with dated techniques. First, the F-22 suffers from an overreliance on stealth, which has been technologically outmaneuvered by both Chinese and Russian air defense designers for almost two decades. Second, the F-22 did not markedly improve range or payload from the 1960s F-15C design. A growing web of anti-access capabilities push these exquisite fighters to ranges approaching their fuel limits in real-world application.

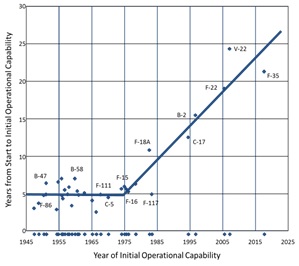

The F-22 first flew in 1997, six years after the YF-22 won the Advanced Tactical Fighter (ATF) fly-off competition and 16 years after the program’s requirements were drafted. It subsequently took 18 years from the first F-22 flight to declaring its initial operational capability in 2005. The snail-like pace of production does not inspire confidence: two aircraft per month at peak production at a plant that would need to be sourced to set up the line.

Despite this, even if the Tactical Air and Land Forces subcommittee inquiry favors restarting F-22 production, the program would have to navigate defense acquisitions roadblocks. Since 1986, acquisitions programs have averaged a lethargic 16 years from contract to combat. A new F-22 would require numerous changes in processing, capabilities, and software coding, all of which would require test and evaluation. All of this makes the timeline a deal-breaker. If you need more proof, look no further than the F-22 increment 3.1 update. It took five years to develop the software and another five years since fielding began, though it’s still not in all six operational F-22 squadrons. That’s ten years and counting. Now envision the time of re-building an aircraft.

The first potential “new” F-22s would field around 2030, only to be dead on arrival by the Air Force’s own estimates. By then, the sixth generation fighter program is expected to begin fielding to replace the original 187 F-22s. This is telling, since studies going back as far as 2009 point to why a replacement F-22/F-35 platform is needed, which culminated under DARPA’s 2013 Air Dominance Initiative.

Designed to last 30 years and 8,000 hours, new F-22s would approach retirement in 2060 if fielded in 2030. While the F-22 will remain the best air-to-air fighter in the world for decades, the same cannot be said for the F-22 as an air superiority fighter. The real threat to the F-22 is probably not a faster, stealthier, more maneuverable fighter. Anti-access/area denial (A2/AD) systems and highly mobile surface-to-air missiles provide a relatively low-cost asymmetric response with a persistent, enduring, and capable threat that is not easily countered. The most potent of these systems are specifically designed to counter stealth. It should be no surprise that they are being built by rising militaries of Russia, China, India, and now Iran. Not only is this detail lacking in a majority of pro-F-22 arguments, it also ignores the fact that these systems were developed after the YF-22 had won the fly-off competition. Why launch a fleet of fighters to counter the F-22 when an adversary need only turn on a ground-based system? Jet-versus-jet comparisons are interesting, but not as compelling to an organization primarily concerned with force projection into foreign lands.

Beyond the avionics, the only things warranting improvement in a new F-22 are range and payload. Those also happen to be the only two things that can’t be changed, thanks to the mold-line restriction inherent in maintaining any semblance of stealth. Addressing these limitations broaches the FB-22 concept, further fragments the discussion, and starts looking more like an entirely new aircraft.

The current low-density, high-demand Raptor fleet is an evolution of preparation for air supremacy, but the character of air warfare is changing rapidly. The F-22 should not be resurrected; instead, the Air Force should continue its evolution to match the pace of the world. Time marches on; it’s time to get in step.

Maj. Mike “Pako” Benitez is an F-15E Strike Eagle Weapons Systems Officer stationed in Europe. He has over 2,000 flight hours, including 250+ combat missions spanning five combat deployments in the Marine Corps and Air Force, and is well-versed in F-22 combat integration. Maj Benitez is a graduate of the US Air Force Weapons School and a former Defense Advanced Research Agency (DARPA) fellow. The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Department of the Air Force or the U.S. Government.

Image: Air Force photo by Senior Airman Kayla Newman