Join War on the Rocks and gain access to content trusted by policymakers, military leaders, and strategic thinkers worldwide.

Nothing endures but change. A Greek philosopher noted over two thousand years ago that nothing is permanent except change. The Marine Corps is an excellent example of this axiom. As a result of internal and external factors, the Marine Corps is continuously adapting to meet new challenges created by changes in the international security environment and the defense resource situation.

-U.S. Marine Corps, Concepts and Issues, Feb. 1989

There is no crystal ball for future wars, but military history provides the next best thing. Decisions made decades ago are making an encore in today’s debate about the design of the Marine Corps. To know where this famed military force is going, one must first see where it has been, by turning to history and sorting through stacks of documents waiting to be read. Studying this past reveals the logic behind the tough choices and trade-offs every commandant must make. And without doing that, one can never understand any particular force design.

Force Design 2030 has a foundation firmly rooted in previous decisions and analyses spanning decades and many commandants while accounting for Title 10 responsibilities, budgetary constraints, and civilian direction. Viewed in isolation, Force Design 2030 seems like an aberration. But this is only because two decades of counter-insurgency warfare distanced the Marine Corps from its past and its institutional memory. If Force Design 2030 does require improvements, any suggestions should first consider the long history of decisions and precedents set over the course of four decades and eleven commandant tenures.

Any discussion on how the Marine Corps got to where it is today should consider external factors, specifically civilian lawmakers, while identifying what does change and what does not across previous and current force design efforts. While the Marine Corps maintains a venerated reverence for the commandant, civilian leaders, specifically Congress, are a large driver of change. Given the subject’s growing importance, reflected by adjacent services now undertaking major force design efforts, this discussion benefits broader defense and governmental pursuits.

With that in mind, I seek here to define force design, identify its most important actors and processes, and explore constraints senior military leaders face throughout force design efforts. I also compare previous force design efforts with Force Design 2030. In doing so, it becomes clear that Force Design 2030 is a well-grounded and researched undertaking, best described as an iterative and logical next step. My conclusion and the evidence stand in contrast to Ben Connable’s recent three–part series in these virtual pages. Unfortunately, Connable relies on an imagined and idealized past to advance his argument, as well as a few significant factual errors about aviation programs. Further, as I discuss later in this article, his critique is overly self-referential, relying on his own work and failing to engage with publicly available data that shaped the decisions of Gen. David Berger, who launched Force Design as the last commandant. Connable never specifies what is functionally wrong with Force Design. Instead, he ignores the fundamental challenge commandants face: balancing resource constraints with the need to produce ready forces.

How to Best Examine Force Design

To truly understand Marine force design, one must do three things: The first is to study naval infantry closely. While the Marine Corps has operated as a second land army frequently throughout history, its future and current operating concepts focus on naval infantry formations. Unfortunately, such cases are limited, presenting a challenge when engaging in force design discussions or providing recommendations. Examining current events in Odessa allows the examination of ground forces operating in the maritime environment implementing force design operating concepts in real-time. However, these cases are also limited. Analysis should also include factors other than force composition. Military change scholar Stephen Biddle indicates it is not necessarily force composition that matters, but how those forces are employed that makes the difference. Plainly, it’s not so much the infantry that matters, it’s how the infantry is used.

Second, force design is a complicated process, and identifying what has or has not changed and what decisions have or have not been made is essential. While critics like Connable often claim the Marine Corps “chopped away at the F-35 to pay for what would become the stand-in-force,” this never happened. Therefore, recommending a “further cut” to the F-35 program is not a viable solution given it is derived from a spurious claim. The Marine Corps only adjusted the levels of each variant to be purchased (less short-take-off-and-vertical-landing and more C-variants). Testimony from the assistant commandant of the Marine Corps clearly states, “We didn’t divest of any tails.” Correctly identifying which assets were or were not divested is key to fully understanding the problem.

Third, any argument that suggests the Marine Corps is rapidly pursuing and adopting technologies should reflect Marine culture accurately. The Marine Corps has not suddenly become a technophilic service. The Marine Corps will traditionally selectively push for cutting-edge technology but is largely resistant to change and averse to technology. Its adoption of advanced systems like the tilt-rotor Osprey and the costly F-35B, as well as the fortunately canceled water-skimming expeditionary fighting vehicle, are examples. Indeed, as Frank Hoffman, a retired marine, argues, “Marines are not nearly as innovative as their culture and mythology depict.” This has a negative impact in today’s dynamic strategic environment and the imperative of deterring peer competitors. His fellow retired marine and scholar Allan Millett notes, “The challenge facing the Marine Corps is whether its military culture, based on human qualities, e.g., loyalty, commitment, and skill, can adjust in a war dominated by microchips.”

It’s not just scholars, former commandant, Gen. Charles Krulak, recognized the Marine Corps was not the innovative service it claimed to be while trying to instill a culture of innovation and change. This aversion to change is surprising given the Marine Corps routinely emphasizes how it’s a service that embraces change, evinced by the opening epigraph. Furthermore, an aversion to technology is at odds with the Marine Corps’ pinnacle warfighting organization — the Marine air-ground task force. In 1962 the Marine Corps established this formation, dependent on organic aviation, cementing the service’s reliance on advanced technologies, specifically helicopters and subsequently advanced fighter jets, in perpetuity. Therefore, any argument that suggests the Marine Corps is careening towards major change should identify how such a situation arose given the Marine Corps’ aversion to technology and change.

Connable and others who argue a lack of “universal character” in warfare provide an absence of evidence regarding change in modern war, not evidence of absence. Therefore, to justify a change in a military organization’s force design efforts or question how service chiefs arrive at certain decisions that have to account for the full universe of possibilities, one ought to investigate cases germane to the discussion. Therefore, exhaustively examining previous Marine Corps force design efforts by dusting off the untouched tomes of military history and articles that have not seen the light of day for decades provides the best possible avenue to understand force design and develop useful recommendations.

It Starts and Ends with Congress

To understand Force Design and the important role lawmakers play in military change, understanding how the Marine Corps was permanently enshrined in statute is essential. In 1946, the 18th commandant, Gen. Alexander Vandegrift delivered his “Bended Knee” speech to the Senate. Vandegrift identified that it was the role of Congress to decide if the Marine Corps was to survive, indicating the key role civilian lawmakers play in military change. While many assume this event solidified the Marine Corps as a military service, this is incorrect. It would not be until 1951 that the Marine Corps would be safe from previous efforts to eradicate it. The 82nd Congress solidified, in statute, the Marine Corps’ organizational structure of three divisions and three aircraft wings, a fixed structure framework which is something no other military service has. The 82nd Congress also identified the Marine Corps as the nation’s force in readiness. Congress determined the Marine Corps would fulfill the role as “shock ground troops for the Nation” remaining “most ready when the Nation generally is least ready,” buying the United States time to mobilize, allowing “the Army and Air Force to concentrate on their major responsibilities of preparing for all-out war.” The Marine Corps, when required, would also serve as a second land army. The Marine Corps’ role as a first responder was, by nature, temporary, quickly responding to an erupting conflict providing the U.S. military time to fully mobilize for conflicts similar to World War II and Korea. The Army and Air Force would execute the “major responsibilities” of the remaining conflict. One could say the original role of the Marine Corps was as a “joint force temp agency,” a term Connable uses derisively. Rhetorically, if the Marine Corps, or any other military service, fails to provide value to the joint force, specifically the combatant commanders, what value are they?

Military change never occurs in isolation. There are two broader events that need to be discussed. First, the way military forces were employed by the United States slowly eroded the Marine Corps’ role as the nation’s force in readiness. Since identifying the Marine Corps as the force-in-readiness, which provided America time to mobilize, the Marine Corps has rarely ever fulfilled this role as originally planned. As U.S. military forces became more frequently used, with a noticeable increase in usage abroad after the creation of the all-volunteer force in 1973, mobilization was no longer a requirement as the United States permanently adopted large standing military forces and has continued to do so for over five decades. This resulted in a permanent presence around the globe by all of the military services. This forward presence limited the requirement for the U.S. military to mobilize for a potential conflict eroding the Marine Corps’ role in buying time for “all-out-war.”

Second, strategies shifted away from conventional forces, including amphibious ships, increasing reliance upon submarines and long-range missiles. In fact, the 25th Commandant, Gen. Robert Cushman, testified before Congress regarding Fiscal Year 1975 funding that his priority concern was amphibious shipping. Archival documents confirm this trend indicating the Marine Corps would be shaped by fewer amphibious ships focused on helicopter operations simultaneously facing declining budgetary resources placing the military services in direct competition with one another for funding. Berger identified this decline in budgetary resources reflected in his planning documents. This assumption reflects the historic norm where budgetary resources allocated to the military have declined over time with two noticeable reversals — Cold War funding beginning with the Carter administration and 9/11. The trend of declining budgetary resources has continued to present day. A missing piece in the argument and recommendations presented is a thorough consideration of finite budgetary resources and how to balance current personnel levels and readiness while modernizing for the future.

Personnel levels for the U.S. armed services have also only increased twice during the existence of the all-volunteer force, beginning during the Carter administration and again during 9/11. Personnel increases correspond directly to the increase in budgetary resources discussed previously. Outside of those two periods, military end strength has largely declined, with Marine Corps personnel levels remaining somewhat constant in comparison to the other military services. What these trends reveal is throughout history, commandants continually face flat or declining budgetary resources with constant or declining personnel levels, having to navigate both.

Regarding the process of military change, prominent scholars indicate civilian lawmakers are instrumental in driving military change. The process of military change, in this case, force design, should take the available resources and furnish the most capable and ready forces given civilian guidance provided in strategy. Congress controls the two largest resources for the military, money and people. Constitutionally, Congress controls the power of the purse. Congress also authorizes personnel levels or military “end-strengths” each fiscal year in the National Defense Authorization Act. Given those two constraints, service chiefs should plan for and implement a strategy for current and future military requirements. These plans should also account for current and future readiness, technology acquisition, rapidly evolving threats and national strategies, and societal demographics — all captured within Title 10 requirements commonly summarized as “man, train, and equip.”

It is worth defining force design in full, something missing in previous discussions surrounding the topic:

Force design contains the Chairman’s recommendations for innovation required to address mid-term to long-term challenges in the strategic environment. Much like force development, force design spans both force development and capability development activities, with an emphasis on long-term solutions to retain a competitive advantage … and address long-term risk over anticipated adversaries and competitors beyond the [Future Years Defense Program]. The temporal window for force design is roughly a decade, starting near the end of the [Future Years Defense Program], looking approximately 5-15 years ahead.

Foremost among the characteristics defining force design is that it is a long-term strategy and endeavor. This emphasizes the importance of researching force design across decades, not years, going beyond fiscal timelines, and a single commandant’s tenure, while avoiding the recollections of individuals who may have observed a fraction of the changes that occurred throughout an organization’s existence. Therefore, in the next section, I provide a comparative assessment of force design efforts spanning four decades and the tenures of eleven commandants.

A Comparative Assessment

While there were previous discussions and studies conducted surrounding Marine Corps unit organization and structure (see, for example, the Hogaboom Report) a prominent discussion regarding the organizational structures and roles of the Marine Corps that mirror Force Design emerged in the mid-1980s. During the tenure of the 28th Commandant, Gen. P.X. Kelley, a discussion of topics included the size of an infantry squad (decreasing from 13 marines to 11, back to 13), with Kelley having to balance decreasing personnel levels while providing an associated “25 percent more firepower as new and improved weaponry came online.” Kelley’s tenure reveals the role technology played and continues to play in offsetting reduced personnel levels. For context, recent articles have claimed the infantry squad debate has been settled when history indicates otherwise. Changes to the size of an infantry squad have and will likely continue given new and evolving threats, technology adoption, operating concepts, and resource constraints. One can easily imagine that as robotics, artificial intelligence, and drones become more prevalent, the infantry squad size and structure will again become a topic of discussion and will likely change in the future.

Kelley’s tenure also included what he categorized as a change in threat resulting in a “crisis” requiring the Marine Corps to develop counter-terrorist forces. Kelley vowed to “be ahead of everyone in this country in developing a viable program to counter this insidious threat.” Kelley forecasted the Marine Corps’ role as a force in readiness continuing to grow as “the distinction between war and peace” became “increasingly obscure.” While not unique to a specific military service or leader, Kelley’s tenure illustrates the undesirable decisions confronting service chiefs having to decide between investing finite budgetary resources into modernization or people. Biddle succinctly captures this tradeoff, “[T]he more we spend on force structure, the less we can spend to modernize equipment.” Decades apart, Berger would face similar challenges, resulting in a new battalion organization mirroring Kelley’s tenure. The new battalion was, “slimmer, saltier and more techy.”

Kelley’s successor, Gen. Alfred Gray, reveals remarkable similarities between the assumptions made by two commandants decades apart. Gray and Berger assume zero growth in the budget. Gray identifies this in Marine Corps 2000, FY90 Manpower Actions, a brief given in Dec. 1989. Berger reflects this in his Force Design 2030 update. This budgetary tension became increasingly evident under Gray. Gray also divested of units overseeing the reduction of infantry battalions while trying to determine “how our forces can best contribute to national security within the constraints of the budget.” Gray reduced infantry battalions from 27 to 24, deactivated aviation assets, deactivated one tank battalion, and reduced and reorganized headquarters across the fleet. Force Design 2030 conducted a similar review of infantry battalions by revisiting a 2016 study, the last study conducted that analyzed the size and composition of the infantry battalion, while also reducing infantry battalions from 24 to 21. The 2016 study is not the first nor likely the last the Marine Corps will conduct on the size and composition of the infantry battalion. To demonstrate just how exhaustive the subject of infantry unit composition can be, an 800-page report was generated in Oct. 1980 titled, “Marine Infantry Battalion 1980-1990 Study Report.”

Gray generated Total Force 2000, a force design effort to increase the reliance upon all personnel within the Marine Corps. Gray would focus the Marine Corps on greater integration of forces, including the reserves, while preparing for the modern battlefield. Perhaps the most striking of all the comparisons is that Gray mentions personnel reforms and organizational concepts identified in Berger’s personnel reforms and Force Design. Gray proposed a higher reliance on the reserves, which Berger also echoed, and organizational concepts that included the divestment of heavy armor while combining reconnaissance and remote-piloted aircraft “into a single unit.” The concept of combining reconnaissance and remote-piloted aircraft into a single unit proposed by Gray in the 1980s was implemented 34 years later by then-Maj. Gen. Francis Donovan and Task Force 61/2. Donovan would employ these units in a tailorable and temporary organization that furthered the capability of the Naval Expeditionary Force in 2022. Insinuating Kelley and Gray preserved some halcyon era of Marine Corps power seems to be a misinterpretation as many of the decisions made by both commandants illustrate similar decisions made by Berger, albeit decades apart. Each commandant had to balance the tradeoff between technology and people, divesting of units and equipment, and maximize the use of reserve forces within the Marine Corps.

The 1990s

As time passes, the differences between Force Design 2030 and previous force design efforts wane revealing remarkable similarities. The 1990s and the end of the Gulf War coincide with major changes within the Department of Defense. At the end of the Gulf War, Gen. Carl Mundy, the 30th commandant, faced a Defense Department review that put every military service in a resource-constrained environment seeking to dramatically reduce personnel levels. Initiated by Secretary of Defense Les Aspin, the Bottom-Up Review began in March 1993. Secretary Aspin ordered the review as he forecasted the U.S. military faced a dramatic shift away from the end of the Cold War now oriented “toward the new dangers of the post-Cold War era.” With the Department of Defense looking to dramatically reduce end strengths, the Marine Corps was expecting a proposed end strength of approximately 159,000 by FY1997. Mundy argued in order to meet the National Military Strategy, the Marine Corps would require an end strength closer to 177,000, a difference of almost 20,000 personnel. The tenure of Mundy mirrors the situation Gen. Robert Neller, the 37th commandant, inherited after two decades of war in Iraq and Afghanistan. Neller’s tenure laid the foundation for subsequent organizational reforms, including Force Design 2030, recognizing the Marine Corps was not organized to meet future threats. Neller also faced budgetary constraints that he determined would impact personnel levels while seeking to preserve highly technical occupations, specifically cyber.

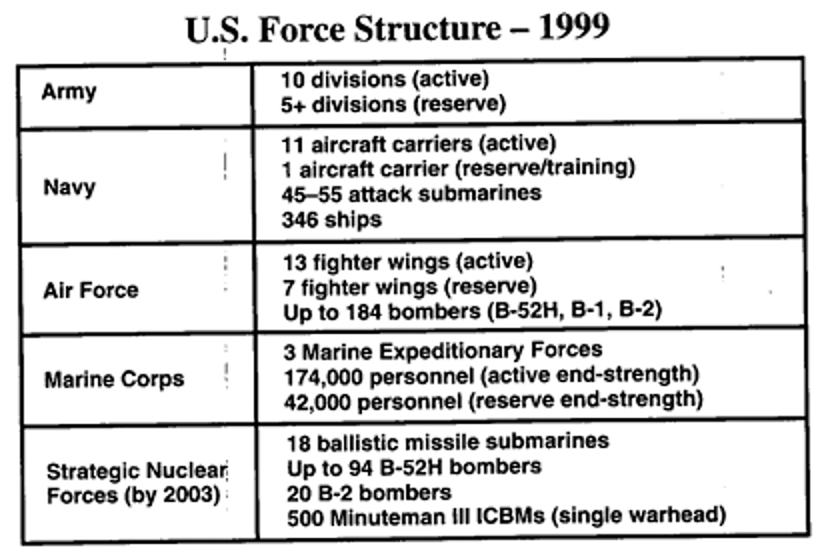

Forecasted U.S. Military Force Structure in 1999, Report on the Bottom-Up Review.

Based on civilian guidance and desires to downsize the Defense Department, Mundy established a “hand-picked planning group” seeking to “preserve those elements of our organization which have continuing relevance and quickly jettison those which do not. What serves us well today might not be what is needed tomorrow.” The hand-picked individuals included many notable names, foremost among them was the chairman of the group, Brig. Gen. Charles Krulak. Krulak would succeed Mundy as the 31st commandant, having orchestrated and supervised the Bottom-Up Review gaining intimate familiarity with the data and decisions made. Krulak determined based on the current projections provided by the Defense Department, “The Corps will be reduced to an active duty end strength of 159,100 by FY97, a reduction of roughly 18 percent from today’s force levels. End strength will be reduced by about 5,800 per year.” The reductions in personnel were forecasted to produce “Smaller, more technology-oriented forces of the future.” Again, the tradeoff between personnel and technology becomes a recurrent theme across commandant tenures.

During Mundy’s tenure as commandant, Krulak chaired the Force Structure Planning Group and delivered a set of radical proposals briefing the General Officers’ Symposium after “8 weeks of intense work.” The conclusions saw the “ground combat element, though smaller, will feature enhanced mobility through increased use of the light armored vehicle (LAV), more reconnaissance assets, and increased lethality with the eventual addition of the multiple launch rocket system (MLRS) as the Marine Corps’ general support artillery of the future.” That sentence from the group could easily be placed within Force Design 2030 revealing how similar the visions are. Even with concerns expressed surrounding Force Design 2030 being “unable to field a Marine Expeditionary Force,” the Force Structure Planning Group planned to eliminate the Marine Expeditionary Brigades and truncate the structure of the Marine Expeditionary Force significantly to meet reduced manpower levels set by the Defense Department.

The most striking similarities between Force Design 2030 and previous force design efforts begin during the tenure of the 31st Commandant, Gen. Krulak. First, Krulak was the first commandant to issue a document known as the “Commandant’s Planning Guidance.” Krulak’s guidance directed the Marine Corps to prepare for an uncertain future while organized “with one goal in mind: success on the battlefield.” Krulak would establish what became known as Sea Dragon to stimulate change within the Marine Corps. Sea Dragon was “a process for change” that emphasized the rate of “technological” change underpinned by the assumption that “the nature of warfare is changing.”

In 1996, Krulak identified the situation the Marine Corps currently finds itself in:

The 21st Century, by all indicators, will be a century of change. Changing global political alliances, demographics, and economic powers, when combined with the rapid infusion of accessible high-technology weapons and information system will change the way our adversaries will fight.

Furthermore, Krulak began the process of reducing the load of the Marine Corps in terms of heavy equipment. Krulak’s tenure saw the Marine Corps “cut 50 percent of our tanks — 50 percent. 33 percent of our tactical aviation went away. 33 percent of our artillery went away. All six of our Marine Expeditionary Brigades went away. One-quarter of our Combat Service Support went away.” In the spring of 1997, Krulak penned, “An Enduring Instrument: The Force in Readiness in National Defense.” Krulak said the Marine Corps must “maintain forces which can conduct discrete, well-tailored and closely coordinated engagements which minimize collateral destruction yet survive against the physical risks of the urban battlefield.” Perhaps in acknowledgment to his predecessors, Berger opens, “A Concept for Stand-in Forces,” stating, “We have been here before.” A careful reading of both documents indicates they are easily interchangeable some 24 years apart.

Gray and Krulak laid the foundation for operating concepts and divestments implemented decades later by Berger, specifically stand-in-forces and the full divestment of tanks. A suggestion to recoup fires (artillery and aviation) and tanks ignores historic precedent and the tenures of three commandants who all made similar decisions to reduce or divest of tank assets. The Marine Corps has already recouped certain aviation fires with the traditional artillery assets maintained able to resource historic Marine Corps requirements. The divestment of tanks supported the Marine Corps’ return to a lighter, more mobile force, while creating cost savings to modernize. Berger was one of three commandants to move away from tanks while modernizing.

The 2000s

If one examines closely when Neller and Berger initiated force design efforts, and where Krulak left off, the two decades at war in Iraq and Afghanistan delayed the force design efforts the Marine Corps is now pursuing. Even with two decades at war, the Marine Corps kept an eye towards the future. The 34th Commandant, Gen. James Conway, whose tenure spanned 2006 to 2010, argued the Marine Corps would satisfy current operational requirements as a second land army while seeking to return to the Marine Corps’ roots as a naval expeditionary force. Conway agreed to 33 ships where the historic requirement was 38, and even planned for a level as low as 30 ships resulting from a joint planning session between the Navy and Marine Corps. What Conway’s tenure confirms is throughout history the number of amphibious ships has and will likely continue to decline, a trend consistently discussed and identified throughout five decades beginning with Gen. Cushman. History makes a strong case that reversing this trend is unlikely.

In transition documents for the Conway effort, four different organizational force designs were proposed for the Marine Corps. Regardless of the proposed courses of action, the iteration and reorganization of forces for future requirements echoes across many, if not all, commandant tenures. Civilian guidance would continue to guide Marine Corps decisions throughout the early 2000s (1997 to 2014) as the Bottom-Up Review solidified into a more permanent process named the Quadrennial Defense Review. The review was focused on many factors to include force structure and modernization.

Somewhere between Conway and Gen. Amos, the Marine Corps returned to an organizational review resembling Krulak’s Force Structure Review Group. The group relied upon similar assumptions mirroring previous and current force design efforts, acknowledging declining budgets and personnel levels. The 35th Commandant, Gen. James Amos, would conduct the force design report, “The Prime Force: Force Design in Fiscal Austerity,” in Jan. 2014. Known as the “McKenzie Report,” the working group was chaired by then Maj. Gen. Frank McKenzie who was tasked to work “for a full month” with the commandant making a “conscious decision to avoid” standard operational planning bodies and processes. This is interesting given the criticisms levied against Force Design 2030 for avoiding the combat development process. The McKenzie Report concluded that for an end strength of 174,000, the Marine Corps would maintain 21 infantry battalions. Future force design efforts, to include Force Design 2030, are well within historic precedent set by previous commandants when choosing to maintain 21 active-duty infantry battalions as the Marine Corps’ end strength during Berger’s tenure in 2023 was approximately 172,500. If anything, Force Design 2030 could have disposed of an additional infantry battalion given the service’s overall end strength.

Amos’ tenure was categorized as one that “leaned hard” into the purchase of advanced military aircraft, jeopardizing Marine infantry. A critical piece of information indicates a commandant years before made the decision Amos was left to carry out. The Marine Corps made the decision to purposefully avoid the procurement of other generational fighter aircraft for over 14 years to pursue a more advanced aircraft later on. Laying the blame for aviation problems at the feet of the Marine Corps’ only aviator commandant is convenient yet inaccurate.

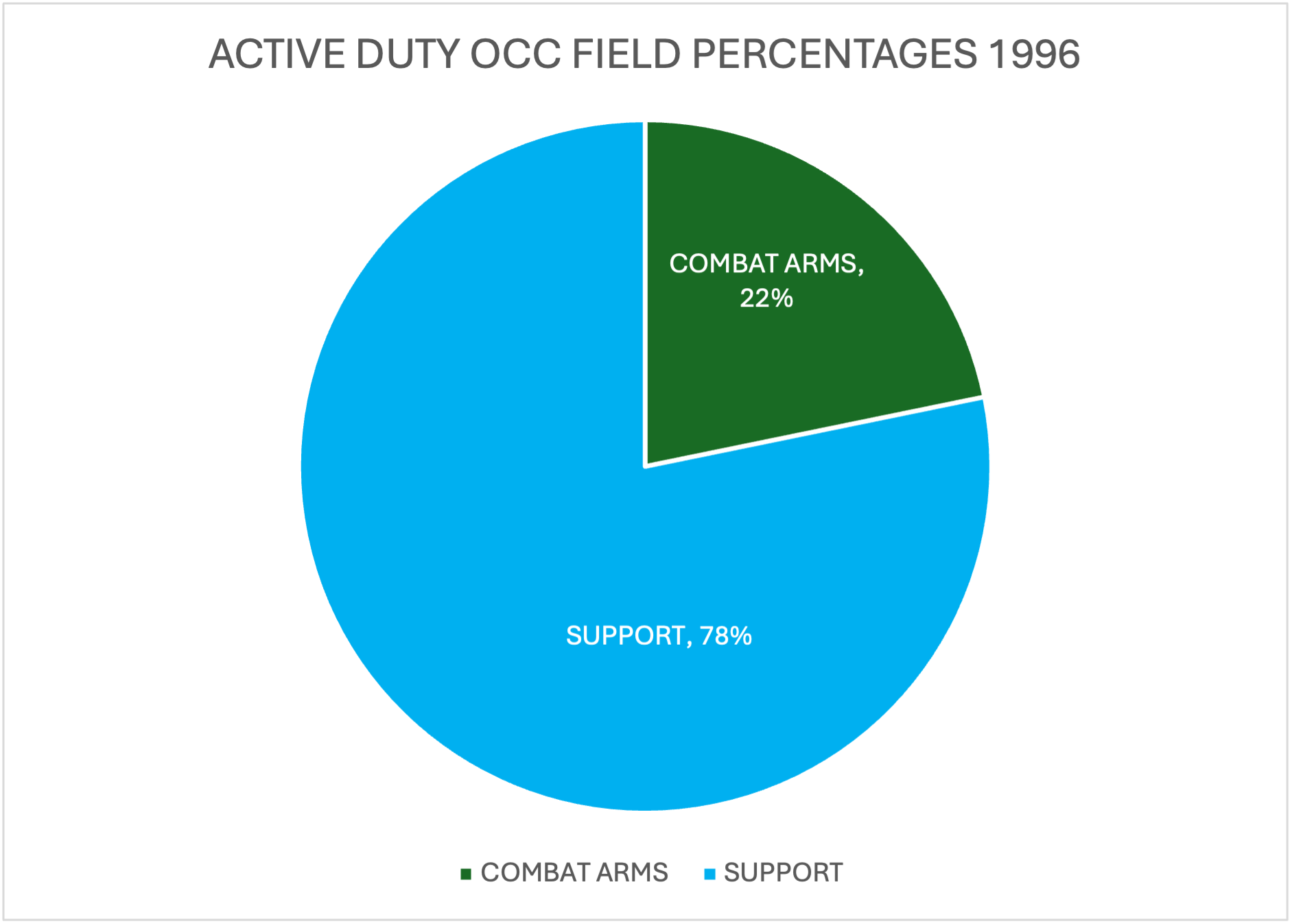

Furthermore, when examining combat arms occupations across time, only a small declination in combat arms occupations (3 percent) occurred in relation to the total force. If infantry remains paramount for future success, Berger’s preservation as a proportion of end strength indicates he understood this [occupational breakdown for active duty graphically depicted below]. In fact, the mixture of occupations has remained fairly consistent.

Headquarters Marine Corps, Manpower & Reserve Affairs, Occupational Levels 1996 and 2024

Conclusion

Former Deputy Assistant Secretary of Defense, Alain C. Enthoven, emphasized when tackling complex policy processes, it is important to, “Study the relevant history, and reflect on its meaning for the current problem.” This perfectly captures the central flaw in recent critiques of Force Design. By focusing on the last 20 years, they miss the constants that have always shaped the Marine Corps throughout history: congressional direction, fiscal reality, and the unending tension between manning and modernization.

While any discussion seeking to improve the Marine Corps is a good one, correctly framing the problem, should remain at the forefront of any effort. Second, the process of military change, in this case force design, should be understood — specifically, how that process occurs, and the important role civilian lawmakers play. Omitting important variables like civilian direction, budgetary constraints, and societal demographics incorrectly portrays historic events given the broader context in which they occur. Given lawmaker support enabled the Marine Corps to acquire additional budgetary resources to pursue Force Design, one can only assume it has the support of the American people. Recent hearings confirm lawmaker support as Rep. Seth Moulton echoed his enthusiasm and surprise after witnessing the progress made by marines toward achieving force design efforts in the Philippines.

Lastly, history is messy, ambiguous, and long. To fully understand everything under the sun is somewhat of a Sisyphean task. However, it should never prevent various intellectuals from pursuing iterative and complementary efforts. While I have identified the shortcomings of previous arguments, I also recognize their value. The discussion of a complicated subject contributes scholarship for future scholars, servicemembers, and senior civilian and military leaders to consider and build upon, including the work I present here. Moving forward, a more prudent approach when discussing force design may be to accept there will be missing pieces of information, and assessing recent decision points with limited access to information becomes problematic.

This does not mean Force Design efforts or commandants are immune from criticism. In fact, I have my own concerns about Force Design related to personnel. Any force design discussion should include the entirety of Title 10 functions. Force design should be about more than just equipping. Given the current secretary of defense’s priorities surrounding budgetary resources, the current commandant, Gen. Eric Smith, again faces the undesirable decision between investing in people or modernization. Any Force Design recommendations should account for the Marine Corps’ current efforts to improve living conditions garnering lawmaker attention resulting from years of deferred maintenance efforts to pursue modernization. Further delays could result in unwanted repercussions in one of the most challenging recruiting environments in the all-volunteer force’s history.

With the Marine Corps’ focus on the Indo-Pacific, an ocean sprawling over 60 million square miles, fulfilling its missions will require improvements in the management of personnel. The historic approach to personnel development remains inappropriate. While the service has made positive progress on this front, work remains to be done. Gen. Neller recently captured this requirement:

The future fight will turn upon the critical thinkers, the problem-solvers who can make instantaneous, high-stakes decisions under duress, leveraging technology rather than being overwhelmed by it. They’ll need to be masters of distributed operations, capable of independent action and rapid collaboration across vast distances and domains … This vision demands we stand our manpower policies on their head.

The azimuth Berger placed the Marine Corps on mirrors the direction, decisions, operating concepts, and guidance issued by multiple preceding commandants, especially Gray, Krulak, Hagee, and Neller. When removing the two decades spent in counter-insurgency operations, Berger seems to have picked up where Krulak, the last commandant unaffected by the events of 9/11, left off. Krulak may now disagree since he has become such a vociferous critic of Force Design.

Gen. Smith’s tenure as the 39th commandant, still in progress, mirrors past commandants discussed herein balancing the drive for change and future preparedness. Smith’s planning guidance indicates comparable planning assumptions while facing budgetary constraints. It is written, perhaps intentionally, to emphasize this interdependent relationship. Smith dedicates an entire section to “The Changing Character of War,” and follows with a section discussing fiscal constraints impacting the Marine Corps’ ability to “drive modernization at speed.” Smith’s guidance discusses key technologies that include “range and precision” weapons, sensors, drones, and loitering munitions reflected in Congressional testimony as required to accelerate Force Design. Smith underscores the totality of Title 10 requirements compels a balance among the “many competing requirements, all of which are important.”

While sifting through piles of articles and documents decades old is cumbersome, it is necessary to assess history properly. Having done that spade work over the last few years, it is clear to me that contemporary force design decisions rely upon decades of iterative efforts guided by lawmaker direction. As Vandegrift noted, it is Congress who decides the Marine Corps’ future, an enduring dictum. If Connable’s argument begins with labeling Force Design as ill-informed, at a minimum he should engage with the research presented here overcoming the decisions made not just by one commandant, but at least five others.

Ryan W. Pallas, Ph.D. is an active-duty Marine officer serving as a commandant strategist at the Schar School of Policy and Government. His research focuses on military change, specifically how personnel policy and management change occurred during the U.S. military’s volunteer era (1973 to 2023). All views are that of the author and do not reflect the Department of Defense or any other governmental agency.

Image: Lance Cpl. Richard PerezGarcia via DVIDS