Join War on the Rocks and gain access to content trusted by policymakers, military leaders, and strategic thinkers worldwide.

Has Beijing found a new “assassin’s mace” to keep the U.S. military out of a fight over Taiwan?

Ongoing debates over how China’s military would counter U.S. intervention often focus on precision strikes against U.S. forces in the Western Pacific. Indeed, some wargames assume that the People’s Liberation Army would throw the first punch. But such a move is not the only option available to China’s decision-makers. Other options include mounting a surprise invasion of Taiwan before the United States can mobilize, pressuring America’s allies to deny U.S. forces access to forward bases, or using strategic deterrence, which seeks to discourage Washington from defending Taiwan in the first place.

Of these options, pursuing strategic deterrence could prove most alluring for Beijing. The logic would be to convince the U.S. government that risks to the U.S. homeland, such as cyber attacks on power grids and telecommunications networks and even the specter of nuclear escalation, are too severe to contemplate. This strategy would leverage China’s expanding nuclear arsenal (and attendant nuclear signals), new intercontinental conventional missiles, space and cyber capabilities, and the belief that Beijing is inherently more resolved than Washington. Chinese leaders who embrace this thinking might conclude that a war could be limited, and thus, they might be more likely to opt for aggression.

To counter the challenge of Chinese strategic deterrence, the Trump administration should further integrate homeland defense with Indo-Pacific regional security. This would ensure unified planning to maintain deterrence both at home and abroad and would convince China that an end run around U.S. Indo-Pacific Command cannot succeed. The administration should also follow a strategic communications campaign to emphasize the grave risks of inadvertent escalation.

U.S. Intervention: A Key Variable in China’s Calculus

China’s military continues to advance towards the deadline that General Secretary Xi Jinping reportedly gave it to be prepared for war against Taiwan by 2027. However, its chances of success remain doubtful, as at least one U.S. observer has recently concluded. Some of the uncertainty can be attributed to Taiwan itself: Under the presidencies of Tsai Ing-wen and Lai Ching-te, Taipei has been enacting long-needed defense reforms, including higher defense spending and a greater focus on mobilization. However, the critical variable for the People’s Liberation Army remains the possibility of U.S. intervention. Officially, the longstanding policy of strategic ambiguity — which President Donald Trump has appeared to endorse — provides U.S. leaders with flexibility on whether to intervene in a Chinese operation against Taiwan and on how to do so. For their part, Chinese sources such as the Science of Campaigns predict U.S. involvement.

The likelihood of U.S. intervention would pose critical challenges for Chinese forces in both major options for using force against Taiwan: a maritime blockade or a full-scale invasion.

Chinese naval and coast guard forces might blockade the island, leveraging their numerical advantage in ships as well as recent exercises designed to simulate blockade activities. However, this move could provoke a U.S.-led counter-blockade operation. This would cause China to be confronted with a difficult choice: either back down and allow some critical imports such as liquified natural gas to reach the island, thus reducing the blockade’s effectiveness, or risk conflict escalation.

In a full-scale Chinese invasion of Taiwan, U.S. intervention could pose grave risks for the People’s Liberation Army. Effective landing operations would almost certainly require maritime and air superiority. U.S. fifth-generation fighters, nuclear attack submarines, strategic bombers, and ground-based artillery and missiles launched from forward-deployed locations in the first island chain would create doubts that Chinese naval transport ships and airborne forces could cross the strait within an acceptable margin of risk. U.S. forces may also include emerging capabilities. In June 2024, U.S. Indo-Pacific Commander Adm. Samuel Paparo drew attention when he stated that a burgeoning stockpile of cheap attack drones would create a virtual “hellscape” for any forces attempting the crossing.

Conversely, the absence of U.S. intervention or major disruptions in the U.S. military’s ability to move forces across the Pacific would improve Beijing’s chances of convincing Taipei to capitulate or defeating Taiwan in an all-out war. A blockade could last indefinitely, with mounting social and economic tolls, while Taiwan’s defenses would struggle in a one-on-one match with Chinese forces given disparities in manpower, platforms, and munitions. Indeed, without the prospect of direct U.S. involvement in the conflict, Taipei might give up without fighting. Understanding these dynamics, Beijing has therefore carefully considered the ways in which U.S. involvement could be minimized or avoided.

A Menu of Options

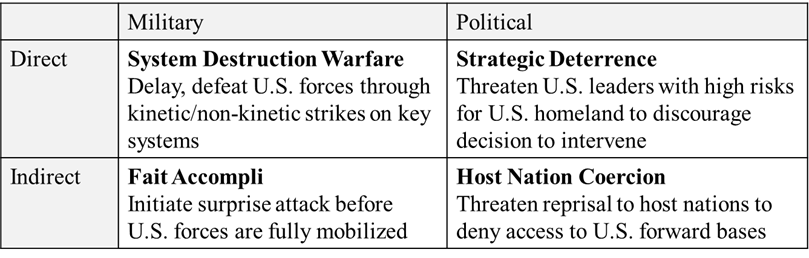

There are four ways in which Beijing may attempt to counter U.S. intervention at the outset of a conflict with Taiwan. Counter-intervention is broader than deterrence because some moves seek to preempt or to defeat, rather than deter, external involvement.

The four options vary along two dimensions: whether the theory of victory rests on military action against adversary forces or on political messaging to foreign decision-makers or whether the option focuses directly on the United States or indirectly on it through actions focused on Taiwan or third parties.

Chinese Counter-Intervention Options

System Destruction Warfare

China could use a range of military tools to frustrate the U.S. military’s ability to mobilize, deploy, and sustain forces in the Western Pacific. Beijing has invested in a large inventory of precision weapons to threaten key U.S. targets such as anti-ship ballistic missiles and air-launched long-range missiles. China might also use non-kinetic strikes, including cyber attacks or electronic warfare, to attack critical U.S. information systems and debilitate U.S. satellites.

For the past two decades, Chinese military observers have discussed such kinetic and non-kinetic strikes as being integral to “system destruction warfare.” The goal of system destruction warfare is to destroy an adversary’s critical military systems — intelligence, surveillance, reconnaissance; logistics nodes; command and control; and combat generation platforms, such as aircraft carriers — while protecting one’s own assets.

The problem with the “system destruction warfare” option is twofold. First, the approach is provocative and highly escalatory. Preemptive attacks on U.S. bases, aircraft carriers, or critical networks would create an escalatory spiral that Beijing could not control and wants to avoid. The second problem is that such attacks might not yield the desired outcome. China might be unable to locate and destroy critical U.S. capabilities, such as attack submarines or strategic bombers operating from bases in the continental United States, which would still threaten Chinese air and maritime superiority. Moreover, the dispersal and concealment of U.S. forces would increase the probability that key capabilities would survive.

Fait Accompli

Given the risk of direct confrontation with U.S. forces, China could instead use limited faits accomplis to expand influence while avoiding potential escalation. For example, China could stage a series of military exercises near Taiwan, which at some point would mask a conventional invasion. Russia skillfully used this tactic before invading internationally recognized Georgian territory in August 2008. If the ruse was successful, U.S. decision-makers would have little time to mobilize forces. However, the scale of a major war could far exceed the requirements of even a large exercise, which would provide warning to Washington. Intelligence could be declassified to deny Beijing the initiative, just as Russia’s attempt to surprise Ukraine in February 2022 was foiled.

Host Nation Coercion

Another option available to China focuses on coercion of third-country government officials. China could try to convince host nations not to allow basing and access to U.S. forces. At the outset of an operation against Taiwan, Beijing would inform the national leaders of South Korea, Japan, the Philippines, and Australia that the use of any facilities by U.S. forces to attack Chinese forces would implicate those countries as combatants and therefore be subject to reprisal. Some governments may yield to Beijing’s demands or limit access to U.S. forces, including expeditionary marine units, tactical aviation, and medium-range missile batteries. Others might resist Chinese coercion, dismissing the threats as merely cheap talk. This option would have less impact on long-range U.S. assets such as bombers that do not require access to close-in basing.

Strategic Deterrence

A final option would be to test the limits of U.S. political resolve to defend Taiwan through a mix of nuclear, non-nuclear, space, cyber, and informational tools. While the concept of strategic deterrence dates to the early 2000s, it gained renewed attention when Xi cited it as a guiding vision of Chinese military modernization in October 2022. Beijing might try to confront Washington with the prospect of a long and costly war that would wreak havoc on the daily lives of millions of Americans. U.S. policymakers may balk, or the Chinese threats could delay a prompt U.S. response as officials debate whether to respond and how to do so. Such a delay would likely hand the Chinese military the initiative in a war over Taiwan.

Xi has been intent on building China’s nuclear forces in recent years. As of December 2024, the Department of Defense reported that more than 600 operational nuclear warheads were produced in the previous year. This number represented a nearly threefold increase from 2020. China has also diversified its nuclear forces to include operational ballistic missile submarine patrols, dual-capable bombers, and intermediate-range ballistic missiles that can carry both nuclear and conventional warheads. These assets could be used in various ways to signal China’s resolve, like how Russian President Vladimir Putin attempted to ward off direct NATO involvement in Ukraine by raising alert levels and conducting snap bomber exercises. Chinese leaders already seem optimistic that such signals could be used in a future cross-strait campaign.

China has also been developing non-nuclear strategic capabilities that could threaten the U.S. homeland. China recently tested an intercontinental ballistic missile — its first such test since 1980. In 2021, it successfully tested a fractional orbital bombardment system that deployed a hypersonic glide vehicle.

Beijing could also threaten major cyber attacks against U.S. critical infrastructure, such as financial systems, telecommunications networks, transportation systems, and electricity grids.

Finally, China could exploit U.S. dependence on GPS and other commercial satellites by threatening to use vast array of direct-ascent anti-satellite weapons and co-orbital satellites as well as “soft-kill” capabilities including jammers and directed-energy weapons.

Taking these possibilities into consideration, China would seek to integrate a range of military and non-military options to threaten the U.S. homeland and discourage the U.S. government from mobilizing forces to defend Taiwan.

A Confidence Game

Broader Chinese attitudes about U.S. commitments and capabilities with respect to a scenario in Taiwan could bolster the plausibility of the “strategic deterrence” option. Beijing’s view of the United States as being in state of irreversible decline — characterized by deep political polarization and economic inequality — could contribute to a perception of weak U.S. political resolve for a long war and could play to the Chinese narrative that reincorporating Taiwan is a core national interest, unlike for the United States.

Growing perceptions that the People’s Liberation Army is eclipsing the capabilities of the U.S. military and that Washington is overburdened by commitments across the globe could also support arguments in China that the United States has little appetite for another conflict.

As a response, the Department of Defense should consider the messages that should be communicated to China’s leaders as it begins work on the next National Defense Strategy. One step should be clarifying that deterrence in the Indo-Pacific and homeland defense are two sides of the same coin, not separate priorities. The next strategy should explicitly connect the two themes to put Beijing on notice that it would, in its own words, be “playing with fire” if it were to threaten any part of the U.S. homeland in the early stages of an operation against Taiwan.

The forthcoming National Defense Strategy should also consider other avenues for messaging to undermine China’s confidence in strategic deterrence. Large-scale military exercises that showcase coordination between U.S. Indo-Pacific Command and U.S.-based forces could be expanded.

The two sides could also resume expert-level dialogues on strategic stability, which could involve crisis simulations and case studies to communicate to China the risks of inadvertent nuclear, space, and cyber escalation that could result from crisis signaling. This could impart a valuable lesson to Beijing, namely that such threats bring escalatory risks.

Finally, the next National Defense Strategy should consider the role that reassurance should play. As Thomas Schelling argued, deterrence and assurance are interrelated. Beijing should be assured that the United States will not change its policy to formally recognize Taiwan’s independence — a clear red line for China — if Beijing refrains from aggressive military action across the strait.

Joel Wuthnow, Ph.D., is a senior research fellow at the Institute for National Strategic Studies at the U.S. National Defense University. He is on X at @jwuthnow.

This essay represents only his views and not those of the National Defense University, the Department of Defense, or the U.S. government.

Image: Lance Cpl. Victor Gurrola