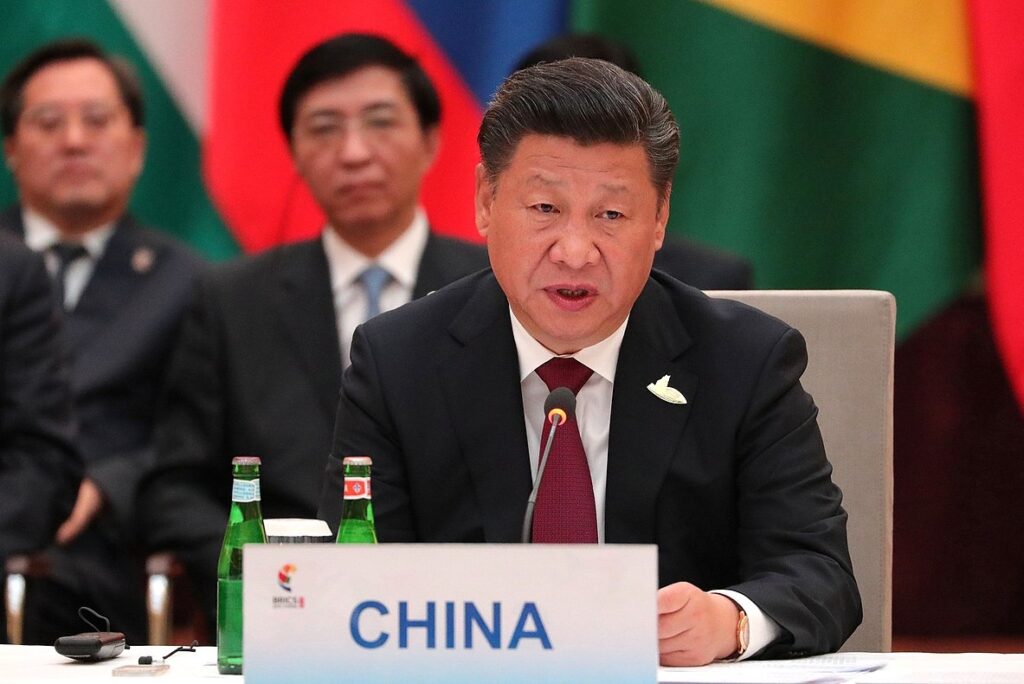

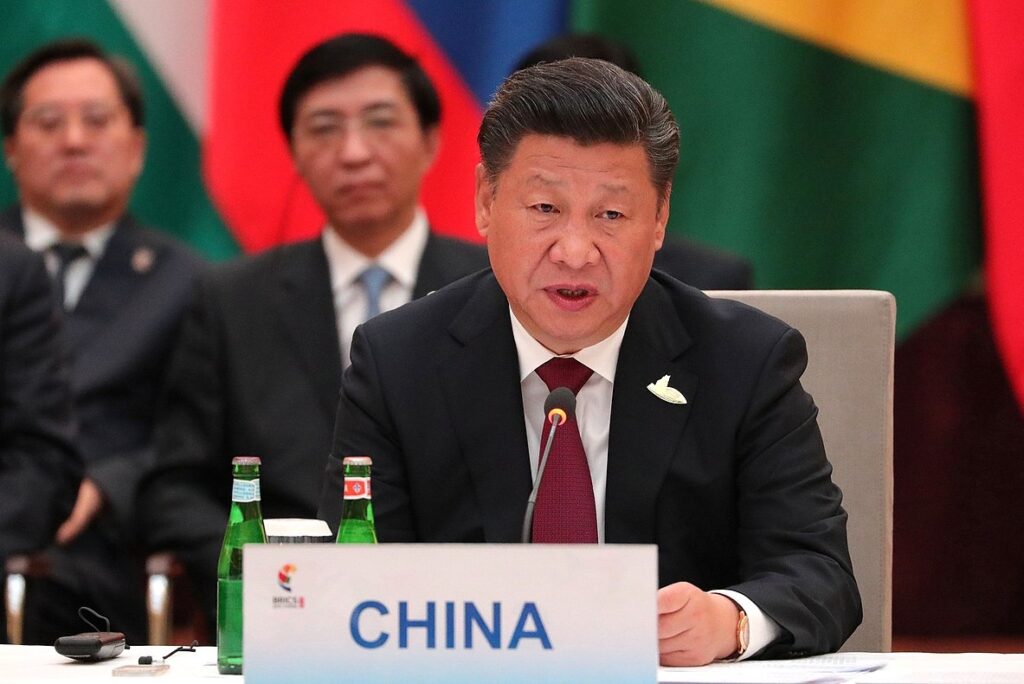

Chinese leader Xi Jinping closed his annual New Year’s address with a pledge to build a “community with a shared future for mankind” and “make the world a better place for all.” A great deal hinges on whether countries in the Global South believe him.

Xi’s language might be dismissed as a rhetorical flourish at the end of a speech noted for reiterating Beijing’s longstanding insistence that Taiwan will “surely be reunified” with China. However, the concept of a “community with a shared future for mankind” (人类命运共同体) is central to Xi Jinping Thought on Diplomacy, the “fundamental guideline” for China’s foreign policy. In the Chinese system, the guiding role of Xi Jinping Thought on everything from “Ecological Civilization” to “Strengthening the Military” derives from Xi’s status as core leader and narrator of the “China story.” Consequently, Xi Jinping Thought on Diplomacy, with its promise of a harmonious Sinocentric future, is held out as a lodestar for the Chinese Communist Party and the Chinese nation to navigate the current period of global upheaval characterized by “changes unseen in a century.” In practice, this involves realizing a post-American international order in which China, in its capacity as self-appointed champion of the Global South, plays a central role. In his U.N. General Assembly address last September, Vice President Han Zheng emphasized that “China is a natural member of the Global South” and “as the largest developing country, it breathes the same breath with other developing countries and shares the same future with them.”

As Beijing grapples with lean economic times and a strategic environment in which the United States retains enduring advantages, Chinese diplomacy increasingly caters to the worldviews of illiberal states in the developing world. This follows the thinking of leading Chinese international relations scholar Yan Xuetong, who posits that a weaker rising power can overtake a stronger established power if it delineates a moral worldview with greater currency in the international community. In its efforts to cast itself as a force for global good, Beijing consistently juxtaposes its commitment to “true multilateralism” with the “selective multilateralism” it ascribes to the United States and its allies. The implicit goal is not multilateralism per se but rolling back what China (and Russia) view as undue American “hegemony” to advance a multipolar world.

In addition to boosting China’s say in the United Nations and other established international bodies, Beijing promotes an ever-expanding array of global and regional “initiatives.” The largest of these efforts are the Belt and Road Initiative and the “Three Major [Global] initiatives” (三大倡议) announced by Xi from late 2021 through early 2023, comprised of the Global Development Initiative, the Global Security Initiative, and the Global Civilization Initiative. The effort to establish China as a global security leader is where Beijing’s formula of high-intensity diplomatic engagement, Sinocentric multilateralism, and appealing to the values of likeminded states in the Global South will be most tested.

While Washington is increasingly concerned with the China challenge, the Biden administration has hitherto avoided the temptation to replicate its focus on competition with China in the Indo-Pacific region to the Global South at large. Assistant Secretary for East Asian and Pacific Affairs Daniel Kritenbrink recently stressed that the U.S. approach to the Global South is not predicated on countering China but based on advancing the vision of “a world where rules, norms and institutions prevail over outdated and dangerous concepts of might making right.”

As many countries are leery of being compelled to “choose sides” in the ongoing U.S.-Chinese geostrategic rivalry, Washington is correct to focus on developing relationships with states in the Global South in their own right. Indeed, many states in Africa, Asia, and the Americas continue to derive immense value from cooperating with the United States to address shared challenges. However, Washington should also grapple with the reality that many countries in the Global South are deeply suspicious of what they see as America’s selective application of the “rules-based international order.” For many such countries, China’s approach connotes greater respect for cultural diversity and collective, versus individual, advancement. Consequently, efforts by Washington to highlight China’s various international initiatives as “Trojan horses” for Chinese influence risk backfiring by playing into Beijing’s depiction of the United States as a decaying imperial power wedded to sustaining its purported “military hegemony” (美国军事霸权) at all costs. In order to avoid this, Washington should modulate its approach towards the Global South, focusing more on specific areas of mutually beneficial cooperation.

Xi Stays the Course

Under Xi, the Chinese Communist Party has committed itself to building “China into a great modern socialist country” that leads the world in “composite national strength and international influence” by mid-century. Enduring asymmetries between the United States and China in key areas, however, present a major roadblock to achieving this goal. While China has made major military modernization progress, these efforts are largely concentrated on developing the capacity to fight and win “informationized local wars” on China’s periphery rather than advancing the People’s Liberation Army’s nascent global power-projection capability. The economic discrepancy also remains sizeable. In late January, the gap between the respective valuations of the U.S. and Chinese stock markets hit $38 trillion, an all-time record. As the Chinese tax system relies on investment-driven growth, this further strains the central government’s already limited fiscal capacity. Nevertheless, a key indicator that Xi is determined to resource his ambitious international agenda in a constrained fiscal situation is that, thus far, tradeoffs have come at the expense of domestic rather than foreign policy budgets. In China’s 2023 central government budget, spending flatlined or was cut in many areas, from rural and urban development to energy and environment, but outlays for defense and diplomacy increased by 7.2 and 12 percent, respectively.

Xi is likely to proceed with renewed confidence in the international arena this year. Following purges of the foreign ministry and military, the core leader will turn to new field commanders to marshal the civilian and military envoys he has called on to forge a “diplomatic iron army.” In late December, former Navy chief Dong Jun was appointed defense minister, a rank-and-file Central Military Commission role whose primary responsibility is liaising with foreign militaries. A new foreign minister, likely Liu Jianchao, currently director of the International Liaison Department, will be officially appointed early this year.

Nebulous by Design

The U.S. Department of Defense’s annual report on Military and Security Developments Involving the People’s Republic of China assesses that Chinese officials have “yet to clearly define how [the Global Security Initiative] would actually advance the vague security goals it espouses, such as safeguarding ‘comprehensive’ security and protecting territorial integrity” and notes that international receptivity to both Global Development Initiative and Global Security Initiative has been “mixed.” The report states that while “[Global Development Initiative’s] links to [the Belt and Road Initiative] have made the initiative more attractive to developing countries,” the Global Security Initiative has gained less traction due to its “vagueness and implicit criticisms of the United States.” However, at this early stage, the nebulousness of the Global Security Initiative may be more of a feature than a bug. The initiative’s loose, non-binding structure facilitates engagement with a Chinese-led security framework with no commitment and minimal cost to the involved countries. Indeed, immediately after Xi announced the Global Security Initiative in April 2022, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs stressed that China “welcomes all countries” to participate. Chinese public diplomacy has sought to contrast the “true multilateralism” practiced by Beijing with Washington’s “Cold War mentality” (冷战思维) that drives the United Statesto organize exclusive “small cliques” (小圈子) such as the Quad and AUKUS in an effort to contain China.

China is promoting its Global Security Initiative as an alternative to U.S. security leadership based on confidence in its greater “moral appeal” to like-minded states in the Global South. The initiative is intended to signal China’s willingness to strengthen cooperation with other nations to manage a tumultuous international security environment and propagate the notion that solutions to pressing global challenges run through Beijing rather than Washington. The State Council Information Office’s recent white paper, “A Global Community of Shared Future: China’s Proposal and Actions,” states that as a “responsible major country,” China seeks to address flashpoints such as the Korean Peninsula, the Israeli-Palestinian situation, and Afghanistan. The paper cites China’s role in facilitating the normalization of relations between long-time rivals in the Middle East, Iran and Saudi Arabia, as a major early success in these efforts.

Chinese analysts generally assume that Western countries are suspicious of the Global Security Initiative. For example, in an article on “Global Security Initiative in the Eyes of Others and their Implications for China,” Li Yan, deputy director of the Institute of American Studies at the China Institutes of Contemporary International Relations (a think tank within the Ministry of State Security), notes the “skepticism” of Western analysts towards the initiative. Li ascribes this suspicion to “anti-China forces” that cast the initiative as a tool by which China seeks to “subvert the international order.” Andrey Kortunov, director general of the state-sponsored Russian International Affairs Council, noted in a recent editorial that the Global Security Initiative was predictably “brushed off by the Western political mainstream as yet another manifestation of the Chinese ‘charm offensive’ in the Global South with very little substance.”

But it is this lack of substance, including the lack of a clear membership structure and veiled yet evident indictment of Pax Americana, that actually facilitates engagement. The initiative’s loose, non-binding structure allows states in Asia, Africa, and Latin America to become involved in a parallel Chinese security framework with minimal trade-offs. Countries that have expressed positive sentiments toward the Global Security Initiative include several authoritarian or semi-authoritarian states such as Vietnam, Saudi Arabia, Thailand, and the United Arab Emirates. All of these states have significant interests in sustaining security cooperation with the United States, but are more ideologically simpatico with China. As the Global Security Initiative is a key element of Chinese diplomacy that is important to Beijing, but generally not regarded as particularly significant by Washington, these countries are able to bolster their ties to China without running afoul of the United States. In essence, the initiative facilitates the predilection of states to hedge on U.S.-Chinese strategic competition.

In a press conference on the Global Security Initiative’s one-year anniversary, Ministry of Foreign Affairs spokesperson Wang Wenbin stated that over 80 countries “have expressed appreciation and support” for the initiative, reflecting the vaguely positive but non-committal responses of many states. For example, during a bilateral between Central Military Commission Chairman Zhang Youxia and Mongolian Minister of Defense Gursed Saikhanbayar, the Mongolian side stated it “resolutely supports” the Global Security Initiative. In their joint communiqué issued at the Third Belt and Road Forum last October, China and Thailand agreed to “explore possible cooperation” through the Three Initiatives. During Xi’s mid-December state visit to Hanoi, Communist Party of Vietnam General Secretary Nguyen Phu Trong stressed that Vietnam is eager to “work with China to build a community with a shared future” and affirmed support for the global initiatives introduced by Xi. In its December 2022 joint statement with China, Saudi Arabia expressed support for the Global Development Initiative, while stating its (more non-committal) “appreciation” for Global Security Initiative.

The willingness of U.S. allies and partners to lend rhetorical backing to the Global Security Initiative highlights a paradox. Many countries in Asia, Africa, and Latin America that rely on U.S. support to address pressing security challenges are also more receptive to China’s framework for global politics predicated on each state’s right to “choose its own development path” (including illiberal ones) than America’s current “democracy versus autocracy” approach. As a result, the Global Security Initiative challenges Washington to formulate a response to the emergence of an alternative, albeit still largely aspirational, China-led international security model centered in the Global South.

America’s Dilemma

The 2022 U.S. National Defense Strategy stresses that success in strategic competition with China, Russia and other revisionist powers necessitates leveraging an “unparalleled and unprecedented network of alliances and partnerships” with “many common values and a common interest in defending the stable and open international system.” However, China’s effort to promote itself as an international security leader is also based on appealing to the values of countries in the Global South, particularly those that have strained relations with Washington. In his April 2022 Boao Forum speech introducing the Global Security Initiative, Xi laid out “six commitments” (六个坚持) including, “respecting the sovereignty, territorial integrity of all countries, upholding non-interference and respecting the independent choices of development paths and social systems made by people in different countries,” and “taking the legitimate security concerns of all countries seriously, including upholding the indivisible security principle.” In practice, this means stronger powers are entitled to regional spheres of influence, as any move by a neighbor to strengthen ties with an external power could be seen as harming the larger state’s “legitimate security concerns” This can be seen in Russia’s interpretation of the indivisible security principle also invoked by Xi as a core value of the Global Security Initiative. Nevertheless, the notion that stronger states should be afforded a degree of deference in their immediate neighborhoods may appeal to partners, especially middle powers in the Middle East, Africa, Asia, and Latin America, who see U.S. democracy promotion, human rights advocacy, and even military intervention as threats.

State media consistently contrasts China’s self-portrayed inclusive security approach with America’s “hegemonic playbook,” particularly on issues where Washington is at odds with a majority of global opinion like the Gaza conflict. As a result, calling out the Global Security Initiative as a Trojan horse for China to enhance its power and influence could backfire by reinforcing Beijing’s efforts to cast the United States as a decaying hegemon mired in a “zero-sum game” approach to international politics. However, Washington would also be misguided to dismiss the initiative as mere propaganda. Indeed, many countries’ wait-and-see attitudes may stem more from concerns about China’s limited staying power rather than from any great attachment to U.S. global leadership. As the People’s Liberation Army’s expeditionary capabilities improve and its overseas presence expands, China’s ability to act as a credible security provider through the Global Security Initiative may also improve.

Conclusion

Even casual observers are likely familiar with the triumphalism of Chinese politics in the Xi era. The glorification of Xi and China’s mixed record during his tenure is increasingly out of step with the experiences of many ordinary Chinese citizens. Nevertheless, it cannot be assumed that Xi will abandon his ambitious foreign policy due to domestic challenges. Long-time China-watcher Bill Bishop noted that the recent Foreign Affairs Work Conference conveys the impression that the current leadership is “very confident” in the trajectory of Chinese diplomacy with little consideration of the risks involved. One such danger is that China, in cooperation with Russia and a host of like-minded authoritarian partners in the Global South, will prove strong enough to weaken the U.S.-led international security order, but not powerful enough to replace it with a viable alternative. Consequently, China’s drive for a “community with a shared future for mankind” is likely to lead not to the harmonious future conjured up by Xi, but to the very entrenchment of bloc politics that Beijing so often rails against.

As Washington becomes increasingly concerned with Beijing’s efforts to overhaul the international order, the United States may be tempted to re-orient its foreign policy to focus on countering China in the Global South. Such a move, however, would play into Beijing’s depiction of a capricious but fading hegemon guided by an anachronistic “Cold War mentality.” But Washington can still strike a balance to engage effectively. This means recognizing that even though the currency of its value-based diplomacy in the Global South is significantly degraded, many countries remain interested in practical cooperation with the United States to address specific challenges.

John S. Van Oudenaren is an independent analyst. He was previously editor of China Brief at the Jamestown Foundation and has also held positions at the National Bureau of Asian Research, the Asia Society Policy Institute, and the U.S. National Defense University.