Join War on the Rocks and gain access to content trusted by policymakers, military leaders, and strategic thinkers worldwide.

Amidst Washington’s push for European support in the Indo-Pacific, has Italy proven overly eager to pivot east? Faced with the choice between directly supporting U.S. efforts to counter Beijing in the region or concentrating resources on emerging threats closer to home, Italy, as one of the most active contributors to U.S.- or NATO-led military initiatives, has opted for the former. Without much debate, Italy has expanded its military presence in the Indo-Pacific, initiating significant collaborations with various regional countries, and deploying naval units to the region. As Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni recently announced, this effort will intensify in 2024, when Rome deploys its aircraft carrier strike groupto the area.

However, Italy’s military engagement in the Indo-Pacific has the potential to backfire. Today, the Italian military is one of the most heavily deployed forces within NATO. Italian armed forces are intensively engaged in Africa, Asia, the Arctic, the Middle East, and the Balkans. They are also heavily deployed in Eastern Europe, contributing to NATO’s deterrence initiatives. Still, despite ranking among the highest contributors to NATO’s operations, Italy occupies one of the lowest positions in terms of allied military spending. So far, Italy has sustained this situation by maintaining a large military force and tilting spending in favor of personnel, thus sacrificing all other expenditure sectors, especially training and maintenance. These elements, however, are a fundamental means to guarantee units’ operational readiness, or the ability of forces to deliver the outputs for which they are designed. In this context, the decision to increase operations abroad can further jeopardize the units’ already deficient level of operational readiness. This is particularly dangerous given Rome’s actual strategic environment.

With the U.S. pivot to Asia and NATO’s renewed focus on the eastern flank of Europe, Italy is now called upon to play a more autonomous role in the increasingly unstable Mediterranean region. Thus, unless Italy significantly boosts the defense budget, directing already scarce resources toward new military efforts away from Europe’s southern flank will likely produce more harm than benefits to Italy and NATO.

A Steadfast Ally

Since 1945, Italy’s policies have consistently aimed at identifying Italy as an Atlantic power and, hence, a loyal memberof NATO. With the end of the Cold War, these ambitions pushed Italy to assume a proactive defense policy, moving from being a consumer of security to a producer of security. From the Gulf War in 1991 to the missions in the Balkans, from Somalia to Afghanistan, from Iraq to Lebanon and Libya, Italian soldiers participated in every important U.S. or NATO military engagement. In comparative terms, Italy seems to have contributed more than other European countries, such as France, Germany, and the United Kingdom. To illustrate, in 2020, Italy was the second largest contributor to NATO’s out-of-area operations after the United States.

Various motivations drive the implementation of this policy. Scholars agree that by presenting Italy as an authentic “international peacekeeper,” military operations play a crucial role in elevating the nation’s global image. Italian policymakers view the involvement of Italian armed forces in regional crises as an instrument to affirm national credibility and reliability abroad, ensuring Italy’s integration within the global community. This policy also provides some protection from criticism that Rome persistently fails to meet the 2 percent of gross domestic product target for defense expenditure set out by NATO. Finally, the operations create an opportunity for the armed forces to bolster interoperability with allies and serve as a motivator for recruitment, as Italian military personnel on missions receive a substantial allowance. Owing to these reasons, Italy’s proactive stance as “the West’s policeman” is praised as a noteworthy contribution to its foreign policy, and it typically benefits from a robust bipartisan consensus, receiving consistent supportfrom both right and left political factions. Consequently, it is understandable that new initiatives in the Indo-Pacific, even if conducted far beyond Rome’s neighborhood, have not been called into question in Italy.

Italy’s Resources and Ambitions

The problem with this view is that it fails to consider all the costs implied by these operations. Other than direct costs (transport, allowances, maintenance, etc.), the decision to deploy soldiers entails significant opportunity costs. These costs reflect the relationship between scarcity and choice — the idea that every choice or decision involves forgoing other options or making other decisions. In this case, investing in new initiatives in the east represents a tradeoff in using already scarce military resources.

An evaluation of opportunity costs can be conducted by assessing whether there are areas of investment that deserve more urgency compared to military operations. Determining the urgency assigned to investments in these areas is subjective. However, if we take the military spending of other major European powers as a reference standard, it is possible to provide some general assessments.

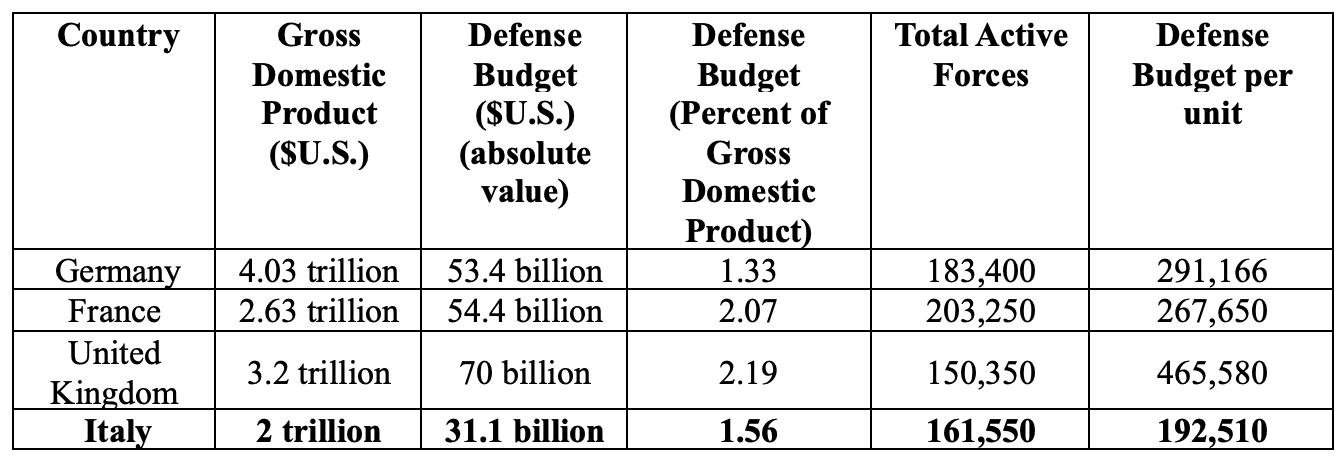

According to the Military Balance 2023, in 2022, Italy spent $31 billion on defense (1.56 percent of gross domestic product), Germany spent $53.4 billion (1.33 percent), France $54.4 billion (2.07 percent), and the United Kingdom $70 billion (2.19 percent). It is immediately apparent that Italy spends much less than other countries. However, absolute figures make little sense unless compared with the number of personnel in service. In 2022, Italy’s total active force numbered 161,050 units, Germany’s 183,150, France’s 203,250, and the United Kingdom’s 150,350. It becomes evident that, despite a budget significantly lower than others, Italy has relatively sizable armed forces. Yet by dividing the budget by the number of personnel, a first considerable deviance emerges between Italy and other European countries: Italy is the country that spends the least money per soldier among the countries considered.

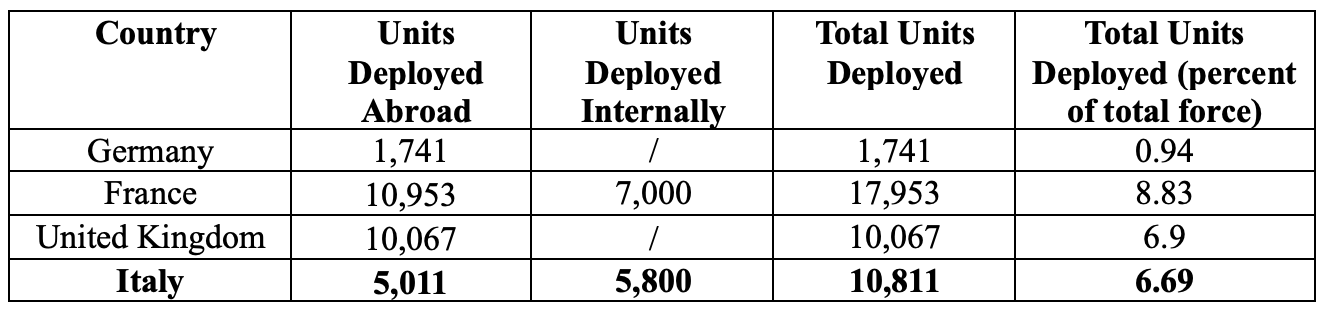

Let’s proceed by analyzing the deployments. According to the International Institute for Strategic Studies, in 2022, Italy deployed approximately 5,000 personnel abroad. Adding personnel involved in domestic operations, the total number of personnel engaged in operations is around 10,800. The United Kingdom deployed about 10,000 personnel, all abroad; Germany deployed approximately 1,741 units, all abroad; and France deployed around 18,000 personnel in operations or “pre-positioning,” with approximately 11,000 abroad and 7,000 in France (forces deployed in territories belonging to the state or in allied territories, except those hosting NATO deterrence initiatives, are not included).

Observing the number of personnel deployed abroad, it becomes evident that Italy is largely in line with other European countries (Germany is the outlier in this case). However, Italy has a considerably lower budget than other European countries. The question, therefore, is how Italy manages to spend so little on such large and actively deployed armed forces. The first answer might be that Italy pays its military personnel lower wages. However, a recent study shows that the salaries of Italian military personnel, even when accounting for purchasing power, are within the European average, if not among the highest. The answer, instead, lies in the distribution of spending.

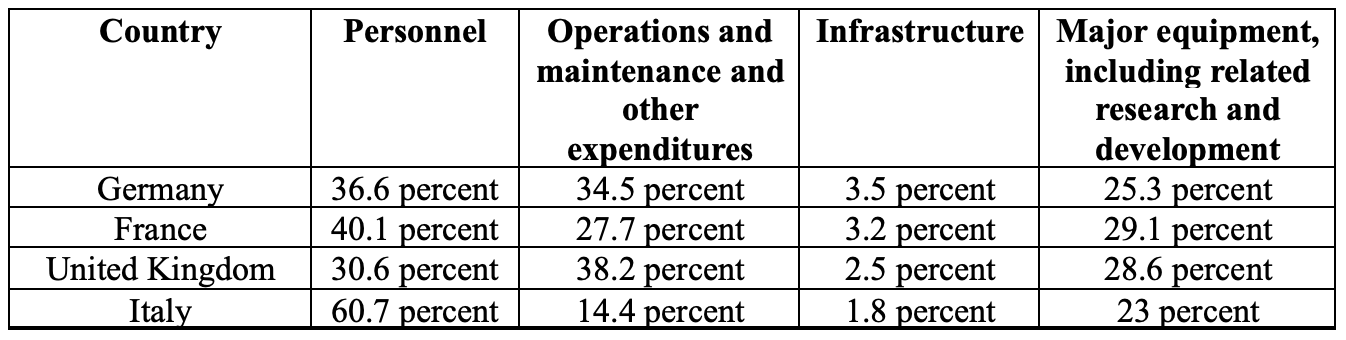

The International Institute for Strategic Studies does not provide comparable data on the expenditure distribution. The most usable data for comparative analysis are provided by NATO, which also makes available figures for the year 2023. NATO divides military spending into four categories: personnel, operations and maintenance and other expenditures, infrastructure, and major equipment, including costs related to research and development. The comparative analysis indicates that Italy deviates substantially from the average European spending distribution. In particular, the analysis reveals three significant deviations from the benchmark set by European major military powers. The first concerns personnel. The table shows that Italy spends over half its budget on this area (60 percent), the second-highest share in NATO after Portugal’s and almost double that of the United Kingdom and Germany. The second concerns operations and maintenance. In this area, Italy spends less than half of the United Kingdom and about half of France. Not even Germany devotes to this area so few resources, a worrying data, considering the Bundeswehr’s widely known “dramatic” lack of unit readiness. The third concerns infrastructure, where Italy’s spending is half that of Germany and almost half that of France. Only the expenditure on major equipment and research and development is reasonably in line with other countries, although still lower than all.

Based on this analysis, it seems reasonable to conclude that Italian defense policy suffers from a misalignment between resources and objectives: Italy endeavors to maintain an excessively large and actively deployed force in proportion to available resources. Maintaining such sizable armed forces allows Italy to deploy many personnel in operations. However, sustaining this policy entails tilting costs in favor of personnel. Under these conditions, the opportunity costs resulting from deploying additional soldiers in operations are considerable, as all funds directed toward operations are funds diverted from harmonizing the spending imbalance. In particular, addressing deficiencies in the operations and maintenance sector is likely the most pressing urgency, as this sector has reached an unacceptable threshold compared to other European powers.

Worryingly, according to Italian strategic documents, resources devoted to operations and maintenance are set to declinein the following years; instead, resources dedicated to personnel will increase further. Even more alarming are Italy’s recent decisions to increase its military engagements further. In 2024, Rome added 1,800 personnel to those engaged in internal security operations. Further, the Italian Ministry of Defense has announced that the Italian military will contribute to the European Union Red Sea naval mission by sending naval and air units and providing the admiral in command.

Given the limited resources available, the risk that Rome cannot deploy operationally ready units is far from remote. Some weeks ago, the British Defense Committee released a report in which it concluded that the British military, which at the end of 2023 deployed 7,000 units, was “consistently overstretched” and lacking readiness. The report’s conclusions are concerning for Italy, which in 2023 spent less than half of the United Kingdom yet maintained a similarly sized military and deployed it with greater intensity.

Italy’s Strategic Environment

Acknowledging that Italy’s decision to expand its military outreach in the east involves sacrificing spending for unit operational readiness, assessing the true magnitude of opportunity costs requires understanding how urgently Italy requires effective forces. This requires a quick analysis of the Italian strategic environment.

According to Italian strategic documents, Italy’s “area of primary strategic interest” is the Enlarged Mediterranean, an area covering the Balkans, North Africa, the Sahel, the Horn of Africa, and the Middle East. In recent years, Italy has repeatedly warned about the complex tangle of security threats emanating from this region. These include terrorism, political and socioeconomic instability, vulnerable energy supplies, and the effects of climate change. The war between Israel and Hamas and the Red Sea crisis are just the latest in a series of events contributing to instability in the region.Indeed, recent months have witnessed a concerning blend of military coups, civil wars, and unprecedented natural disasters, heightening insecurity in North Africa and the Sahel regions. Adding to the challenges, Russia and China are expanding their influence in Africa and the Middle East, fostering anti-Western and anti-NATO sentiments through disinformation campaigns. While China relies on economic agreements and infrastructure projects, Russia capitalizes on existing instability, forming security cooperation agreements, consolidating military presence, and deploying private military companies in various African nations. Evidence suggests Russian mercenaries’ involvement in military operations and atrocities against civilians. Additionally, Russia has become the top weapons exporter to Africa, accounting for 40 percent of large weapons system imports between 2018 and 2022. Moscow also maintains a formidable naval squadron in the Mediterranean, featuring advanced submarines and conducting regular exercises with countries like Algeria and Egypt.

Concurrently, with an increase in instability on the southern flank of Europe, the NATO and U.S. commitments to the area have declined. This is especially true after Russia’s attack on Ukraine, which inevitably directed Europeans’ attention toward Russia. This means that Southern European allies are now forced to play a more active role in ensuring security on NATO’s southern flank. Italy, being the primary European military power facing the Mediterranean, is expected to play a leadership role in this effort. This is an unprecedented role for a country that has always conducted its military intervention policies abroad acting as a “follower.” Italy’s ability to successfully assume this role and promote stability in the Enlarged Mediterranean will crucially rely on its armed forces and their ability to effectively deliver the output for which they are designed.

Conclusion

The analysis conducted in the article brings to light two key aspects that are essential in evaluating the wisdom of Italy’s decision to expand its military presence beyond the Enlarged Mediterranean. The first concerns Italy’s defense policy. In this regard, the data indicates a mismatch between resources and ambitions. While Italy does not have the same resources as other major European countries, it aspires to have armed forces that are equally extensive and engaged, if not more so. To sustain these ambitions, Italy skews spending in favor of personnel, thus paying a high opportunity cost in terms of the operational readiness of its troops. The second concerns Italy’s role in the Enlarged Mediterranean. The analysis highlights the escalating instability in NATO’s southern flank and the growing need for Rome to play a more proactive role in the region. It highlights the urgency for Italy to possess armed forces that are exceptionally ready and effective for engagement in this area.

Given these circumstances, recent Italian initiatives to the east should raise concerns. Since Italy, as outlined in the latest Defense Planning Document, does not intend to deploy significant investments for defense in the next two years, these new initiatives imply that other resources will be redirected to operations rather than training and maintenance. While this approach does not necessarily question Italy’s ability to deploy units within and beyond the Enlarged Mediterranean, it does question its ability to deploy operationally ready units. This poses a risk that Italy and NATO today cannot afford. Both would be better off if the Italian armed forces reduced their ambitions, concentrating on deploying fewer but more prepared units on NATO’s southern flank rather than continually expanding their presence abroad and risking the dispatch of unprepared units.

Matteo Mazziotti di Celso is a PhD candidate in security and strategic studies at the University of Genoa (Italy) and a research fellow at the Center for Geopolitical Studies. He is also a captain in the Italian Army. The views expressed in this content are those of the author and do not reflect the official position or opinions of the Italian military.

Image: Italian Navy