Join War on the Rocks and gain access to content trusted by policymakers, military leaders, and strategic thinkers worldwide.

The fall is an ideal time for a visit to Taipei — as the military planners for the People’s Republic of China plotting a cross-strait invasion know all too well. Weather and ocean states in October, much like in March through April, provide Beijing a favorable window to attempt an invasion of Taiwan. This October, American and Japanese forces conducted an operationally focused bilateral exercise, rehearsing missions that would have been unthinkable a few short years ago but that now prove vital when deterring Chinese aggression. Resolute Dragon 23.2 not only demonstrated each force’s lethality and interoperability but also strengthened their military partnership in defense of Japan.

As Japan and the United States continue to enhance their military readiness and lethality, the Japanese Ground Self-Defense Force’s Western Army and III Marine Expeditionary Force deployed across Japan to demonstrate credible capabilities, strengthen deep partnerships at all levels, and stress-test the integration of nascent equipment. Ultimately, the combined deployment of personnel and equipment across Japan culminated with a live-fire exercise in Hokkaido, where forces welded together links of the bilateral kill chain. The successful execution of Resolute Dragon 23.2 is much more than just a message of assurance to the people of Japan and a warning to malign actors in the region — it is also a tangible demonstration to regional partners of what is possible when working together to stem the aggression of the People’s Republic of China.

But fighting side by side with an ally is not enough. For the next step, the Marine Corps ought to expand and deepen its alliance coordination capabilities within the First Island Chain, as per former Assistant Secretary of Defense and retired Marine Lt. Gen. Wallace Gregson’s recommendation to “make expanded use of forces and personnel already in Japan.” Simple, thoughtful investments aimed at reframing how the joint force prepares its personnel and how it participates in bilateral exercises and operations will be key to victory within the First Island Chain. The joint force should foster deeper alliance coordination expertise within every service, across the ranks and military specialties, to demonstrate its commitment to allies and partners across the Pacific.

Right Ally, Right Place, Right Time

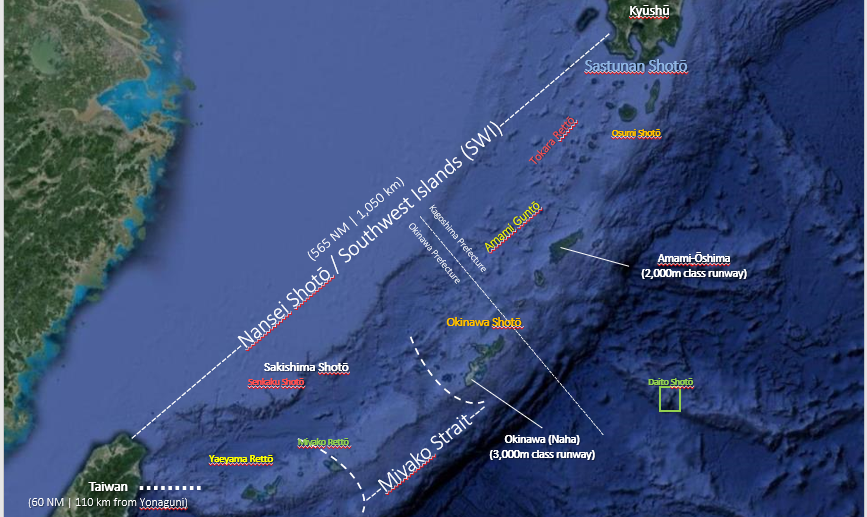

Resolute Dragon 23.2 differed from its previous iterations in the scope and scale of the exercise as well as the number of bilateral participants. For example, Resolute Dragon 21 and 22 occurred in northern Japan, whereas this iteration placed forces on the Sakishima Island chain, the southernmost part of Japanese sovereign territory. In addition, elements of the Army Multi-Domain Task Force participated in operations on Ishigaki. III Marine Expeditionary Force and the Japanese Ground Self-Defense Force placed coordination nodes across the Sakishima Islands. The bilateral forces occupied various installations from Hokkaido to the Sakishima Islands, far exceeding the number of installations employed during previous exercises. The robust staffing and proper equipping of a bilateral ground operations coordination center gave the Western Army and III Marine Expeditionary Force the ability to synchronize, coordinate, and deconflict missions. All told, 3,300 personnel from across the joint force and 5,000 members of the Japan Self-Defense Force participated in Resolute Dragon 23.2.

The geography of Resolute Dragon. Map by Maj. Chris Denzel based on an image from Google Maps.

During Resolute Dragon 23.2, the Japanese Western Army’s appetite for partnering extended to rehearsing realistic mission sets on key maritime terrain rather than just the static live-fire ranges and basic knowledge exchanges typical of security force training exercises. As a result, operations, activities, and investments today continue to build our partner force capacity but also tackle how to conduct alliance coordination between the joint force and regional partners, from collaborative planning to interoperable data and technology systems. As the goals and needs of the partners change, partnering adapts.

Coordination

The complexity of the mission to defend the Sakishima Islands requires the collocation and alignment of the warfighting functions of two three-star commands. During Resolute Dragon 23.2, III Marine Expeditionary Force personnel served as the nucleus of a regional bilateral ground operations coordination center, creating a vital alliance coordination center between the force and the Western Army. The nature of the American and Japanese parallel command structures requires a coordination center to bring to bear the full capabilities of each force. Access, basing, and overflight alone will not suffice during a crisis. The joint force requires a U.S.-Japanese alliance coordination capability able to see, understand, and affect the battlespace. In this case, the bilateral ground operations coordination center for Resolute Dragon 23.2 fits the bill, but there is still much room for improvement during real-world operations.

The Resolute Dragon 23.2 partnership served an example of how U.S. forces and regional partners will align effects during the deliberate, joint, combined, partnered deterrence campaign in the First Island Chain. The bilateral ground operations coordination center facilitated integrated planning that harnessed and accentuated each command’s capabilities. During conflict, this mechanism would prove invaluable. During the exercise, III Marine Expeditionary Force and the Western Army coordinated, synchronized, and deconflicted mission requirements. Each command demonstrated how they could coordinate across warfighting functions, building a single, accurate picture of the bilateral fight, mitigating the demands of conflict. The scale and scope of these combined exercise objectives were unthinkable a few short years ago. The present threat environment now makes this level of coordination essential.

Next Steps

With this in mind, the Marine Corps should explore the expansion of its allies’ and partners’ coordination cells within the First Island Chain. Developing a physical space is secondary to developing the personnel who will operate inside vital coordination centers throughout the Pacific. Building upon the momentum generated by operations, activities, and investments within the First Island Chain, the Marine Corps should further develop a cadre of officers and enlisted capable of strengthening partnerships within the Pacific. Heeding the Commandant of the Marine Corps’ direction for every Marine to increase their experience and expertise in the western Pacific, the service should explore the development of a program like the Afghanistan-Pakistan Hands, with a specific operational focus tailored to supporting the mission requirements of the joint force and its regional allies in the Pacific. Such a program will facilitate information sharing and integrated planning, while posturing partners for close coordination in crisis response and ensuring operations, activities, and investments build upon one another.

Improving alliance capabilities in the Pacific is a joint concern, not just a focus for one service. All services should be prepared to respond to a crisis, and alliance coordination mechanisms will be critical for all involved in manning, training, and equipping the joint, multilateral force across the Pacific.

The degree of success of U.S. Indo-Pacific Command will depend on each service’s ability to assume alliance coordination roles and responsibilities. Depending on the threat environment, the character of competition and conflict may make one service component better suited than the others, and that character can change over time. Service components should prepare subordinate units to assume bilateral and multilateral mission sets on demand. Foreign area officers and defense attaches cannot and will not do it alone. Any member of the joint force should be capable of integrating with allies across warfighting functions, regardless of their rank and specialty, to advance joint and bilateral goals. Alliance coordination is not an advise-and-assist mission for specific echelons of command but rather an integration and accentuation of partner capabilities at every level from junior enlisted to flag officers.

Conclusion

Resolute Dragon 23.2 reaffirmed the Japanese-American alliance while revealing opportunities to further strengthen it. During the exercise’s final days, U.S. Ambassador Rahm Emanuel visited troops in Hokkaido while Commandant of the Marine Corps Gen. Eric Smith hosted Koji Tomita, the Japanese ambassador to Washington. These engagements highlight the importance of allies training side by side. As with Balikatan 2023, strategic messaging shows how diplomatic and military efforts complement one another.

The threat window for northeast Asia varies throughout the year due to weather and ocean conditions. For the joint force and its partners, well-timed bilateral exercises not only serve as a chance to strengthen military partnership but simultaneously deter Chinese aggression within a threat window. Operations, activities, and investments in the First Island Chain will continue drawing partners together and serve as a template for how the joint force will meet the needs of their partners in the face of any future threat.

Col. Bill Matory serves as the 3rd Marine Expeditionary Brigade operations officer.

Maj. Benjamin Van Horrick is the 3rd Marine Expeditionary Brigade current logistics operations officer.

The views presented are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the policy or position of the U.S. Marine Corps and the Department of Defense.