In the past, headlines about the Pentagon failing its financial audit again would never have caught my attention. But having been in the middle of this conversation when I served on one of the Defense Department’s advisory boards, I understand why the Pentagon can’t count. The experience taught me a valuable lesson about innovation and imagination in large organizations, and the difference visionary leadership — or the lack of it — can make. With audit costs approaching a billion dollars a year, the Pentagon had an opportunity to lead in modernizing auditing. Instead, it opted for more of the same.

Auditing the Department of Defense

By law, the Department of Defense has to provide Congress and the public with an assessment of where it spends its money and to provide transparency of its operations. A financial audit counts what the Department of Defense has, where it has it, and if it knows where its money is being spent.

Auditing the Department of Defense is a massive undertaking. For one thing, it is the country’s largest employer, with 1.3 million people on active duty, 800,000 in the reserve components, and 770,000 civilians for a total of 2.9 million people. The audit has to count the location and condition of every piece of military equipment, property, inventory, and supplies. And there are a lot of them. The department has over half a million assets, from buildings to pipelines to roads and fences located on over 4,860 sites, as well as 19,700 aircraft and over 290 battle force ships. To complicate the audit, the department has 326 different and separate financial management systems, 4,700 data warehouses, and over 10,000 different and disconnected data management systems.

This is the fifth year the Department has undergone a financial statement audit and failed it. It was not a trivial effort, requiring 1,600 auditors — 1,450 from public accounting firms and 150 from the Office of Inspector General. In 2019, the audit cost $428 million in auditing costs ($186 million to the auditors along with $242 million to audit support) and another $472 million to fix the issues the audit discovered.

Let’s Invent the Future of Audit

The Defense Department’s 40-plus advisory boards are staffed by outsiders who can provide independent perspectives and advice. I sat on one of these boards, and our charter was to leverage private sector lessons to improve audit quality.

With defense spending on auditing approaching a billion dollars a year, it was clear it would take a decade or more to catch up to the audit standards of private companies. But no single company or even entire industry was spending this much money on auditing. And remarkably, the Defense Department seemed intent on doing the same thing year after year, spending more resources to get incrementally better. It dawned on me that if we tried to look over the horizon, the department could audit faster, cheaper, and more effectively by inventing future tools and techniques rather than repeating the past.

Our charter didn’t ask the advisory board to invent the future. But I found myself asking, “What if we could?” What if we could provide the department with new technology, new approaches to auditing, analytics practices, audit research, and standards, all while creating audit and data management research and a new generation of finance applications and vendors?

The Pentagon Once Led Business Innovation

I reminded my fellow advisory board members that in 1959, at the dawn of the computer age, the Defense Department was the largest user of computers for business applications. However, there was no common business programing language. So, rather than wait for one, the Defense Department led the effort to create one — the COBOL programming language. And 20 years later, it did the same for the ADA programming language.

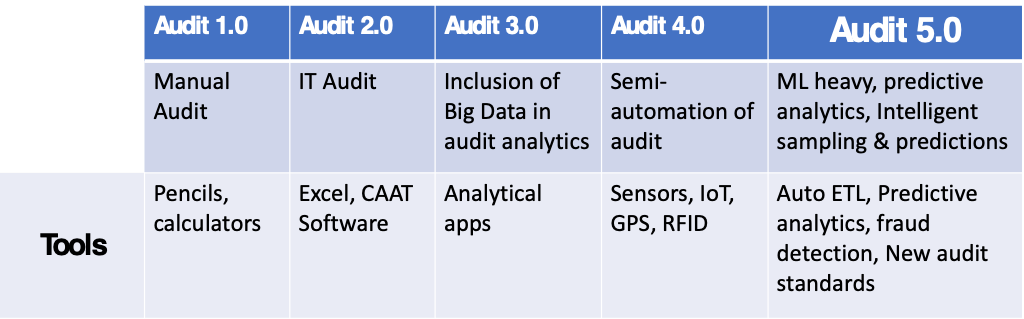

With that history in mind, I proposed we lead again. And that we start an initiative to create the 5th generation of audit practices, one which could utilize machine learning, predictive analytics, intelligent sampling, and predictions. This initiative would also include automating data transfer and integration, fraud detection, and a new generation of audit standards.

The program wouldn’t even need more funds, since the Department of Defense could allocate just 10 percent of the $428 million it was spending on auditors to fund Small Business Innovation Research programs in auditing/data management/finance, generating five to ten new startups in this space each year. Simultaneously, we could fund academic research, to incentivize research on Machine Learning as applied to the challenges a machine learning approach would face in finance, auditing, and data management.

In addition, we could create new audit standards by working with existing government audit standards bodies. We could collaborate with civilian audit standard bodies, such as the Auditing Standards Board and Public Company Accounting Oversight Board. Working together, the department could create the next generation of machine-driven and semiautomated standards. Furthermore, such a plan could help the independent public accounting firms create a new practice and make them partners in the initiative.

By investing 10 percent of the existing auditing budget over the next few years, these activities would create a defense audit center of excellence that would fund academic centers for advanced audit research, standup “future of audit” programs to create 5-10 new startups each year, be the focal point for government and industry finance and audit standards, and create public-private partnerships rather than mandates.

Spinning these activities up would dramatically reduce the department’s audit costs, standardize its financial management environment, and provide confidence in its budget, auditability, and transparency. And as a bonus, it would create a new generation of finance, audit, and data management startups, funded by private capital.

The Road Not Taken

I had been in awe of my fellow advisory board members. They had spent decades in senior roles in finance and accounting in both the public and private sectors. Yet, when I pitched this idea, they politely listened to what I had to say and then moved on to their agenda — providing the Defense Department with incremental improvements.

At the time I was disappointed, but on reflection not surprised. An advisory board is only as good as what it’s being chartered and staffed to do. If it is being asked to provide a 10 percent incremental advice, they’ll do so. But if they’re asked for revolutionary advice, they can change the world. But that requires a different charter, leadership, people, innovation, and imagination.

In the end, the Department of Defense, the largest purchaser of accounting services in the world, ignored a chance to take the lead in creating the next generation of audit tools and services, not only for financial audits but for the hundreds of billions of dollars of acquisition contracts the Defense Contract Audit Agency audits. By now the department could have had audit tools, driven by machine learning algorithms, ferreting out fraud by vendors or contractors and anticipating programs that are at risk.

If you only get what you ask for, you haven’t hired people with imagination. America’s defense leaders ought to ask and act for transformational, contrarian, and disruptive advice, and ensure they have the will and organization to act on it. It is time to stop requesting advice for incremental improvements and instead ask the consulting firms how to best serve the Defense Department and taxpayers. Defense leaders need to consider whether spending a billion dollars a year for an audit is causing the department to become appreciably more efficient or better managed — or whether there might be a better way.

Steve Blank is an adjunct professor at Stanford and a founding member at Stanford’s Gordian Knot Center for National Security Innovation. Steve consults for the national security establishment on innovation methods, processes, policies, and doctrine. Steve’s latest class at Stanford, Technology, Innovation, and Great Power Competition, is providing crucial insight on how technology will shape all the elements of national power.

Image: Department of Defense