As the United States withdrew from Afghanistan last August, images of Taliban soldiers decked out in American kit frequently recurred on global media. Social and news media fretted that the Taliban had become the only terrorist group with an air force. Much of the ado might be about nothing. The complex and exquisite platforms that provoked the most concern (i.e., Black Hawks and light attack airplanes outfitted with Hellfire missiles), require capacity to train, field, and maintain that is probably beyond the Taliban.

The large volume of small arms and light weapons the United States left behind is more mundane yet more meaningful. Based on the 2017 Government Accountability Office and 2020 Special Inspector General for Afghanistan Reconstruction reports, the cache exceeds 650,000 pieces ranging from rifles to rocket-propelled weapons. Unlike Black Hawks, they require little training and no expertise to use. Even fresh Taliban foot soldiers know how to fire an AK-47. Beyond that, their qualities, combined with state weakness, have led to weapons diffusion into the surrounding region, sparking and inflaming more violence. In short, the enormous stockpiles left behind have generated a “regional arms bazaar” for terrorists, criminal elements, and insurgents.

This has happened elsewhere before and will again. The risk that weapons deployed in the Russo-Ukrainian War, whenever and however it ends, will disperse across Eastern Europe and Central Asia is particularly disquieting.

Weakly governed states — whether weakened by corruption, conflict, or collapse — have looser arsenal integrity, making them more subject to opportunistic substate groups. Their weakness allows apertures into the black market, the size and reach of each being a function of how well-armed the state and how weak its stockpile security. On the smaller end, corrupt nations control a more trickling leakage of arms into the black market to a shortlist of proxies and clients, usually with conditionality. Depending on the scale, actors, and victors, post-conflict scenarios can range from a few loose arms to largescale diffusion.

On the extreme end of the state weakness spectrum, collapse generates the most pointed proliferation events, especially if the nation was well-armed. We focus on these moments as sudden, immense shifts in black market volumes and movement. Following collapse, stockpile security folds along with the government’s legitimacy, institutions, and services. In addition to the usual black-market tradesmen ready to plunder national arms depots, many regular citizens join out of desperation as a new anarchy takes hold. In fact, weak governance becomes a simultaneous cause and consequence of weapons looting since the state can neither provide security for citizens nor secure stockpiles from citizens. These reinforcing conditions — elevated demand, vulnerable supply — intensify the siphon of weapons from the state to the local black market.

The larger the stockpile and the more suddenly it devolves to nonstate actors, the more intensely it tends to diffuse into the surrounding region. Local actors arm themselves and warlords offer provincial security, but weapons are also a lucrative commodity. In insecure environments, sales might purchase safety, basic goods and services, or escape. They might buy loyalty and solidify substate alliances. With a sated national market, would-be customers having plundered their own caches to surplus, illicit entrepreneurs look abroad for markets of higher profit and demand.

And there is demand. Considering the case of Libya in 2011, for example, demand might come from rebels (Darfur fighters), insurgents (Seleka in Central African Republic), militias (Azawad factions), terrorists (al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb), criminals (Tibesti gold rushers), gangs (Nigerian “bandits”), or even civilians seeking self-defense. Although not sufficient for violence without motive, arms are a necessary precondition for violent campaigns of any kind.

We point specifically to small arms and light weapons. They are distinctly suitable for sale, in contrast to heavier systems (recall the missile-laden light attack planes in Afghanistan, for instance). The capacity requisites for complex weapons render that market significantly smaller and more specialized. Many ragtag looters lack access or would not risk exposure to such in-groups. Selling nations also maintain end-use monitoring on conventional platforms, making it even riskier. Small arms and light weapons, however, are financially and technically approachable even for foot soldiers. Existing monitoring mechanisms for the latter are also fragmented and ineffective, dramatically reducing the risk of being caught.

The qualities of small arms and light weapons also make them distinctly amenable for trafficking. Also unlike heavy weapons, they are small and modular enough to be hidden at checkpoints and among “ant-trade” transports. (Ant-trade is a term of art for the most common form of illicit weapons trafficking: Imagine ants following their routes, spaced out with one load at a time. Traffickers mimic this to avoid riskier, costlier interceptions.) They are more durable, needing minimal upkeep and maintaining value across exchanges and time. They are also more serviceable, requiring minimal cost for replaceable parts and ammunition.

The combination of weak governance, local incentives, and the attributes of small arms and light weapons ejects them into the surrounding region following collapse. This influx of weapons — larger and more diverse than the usual sources that illicit actors tap — augments substate forces and their fighting capacity. Since more than 90 percent of contemporary armed conflicts are now internal, and since small arms and light weapons are the currency of substate violence and its spread, these massive proliferation moments are grim.

Depending on the destination, dispersion could mean a number of things. We return to the Afghanistan case to demonstrate a few of them. Dispersion might simply exacerbate instability in weak zones, like it has in Afghanistan itself and certainly pockets around it in Pakistan, Iran, and India. Weapons diffusion might revitalize insurgent efforts, such as that of the separatists in Baluchistan, or strengthen existing terrorist organizations, like the Islamic State affiliate in the region and al-Qaeda. It might create political space, full of arms and anarchy, for new terrorist groups and rebellions to arise. For instance, Afghan tribal groups are coalescing in opposition to the Taliban. Perhaps worst, it can incite or bolster civil war. Factions within the Taliban are vying for dominance, and it is unclear how far the internecine struggle will escalate. We also find it feasible that Western arms abandoned in Afghanistan could be trafficked to existing conflict zones in Iraq, Syria, or Yemen, especially with Iran’s support. The upshot is that the supply of small arms and light weapons interacts with the demand dynamics at trafficking terminuses, yielding a spectrum of potential outcomes.

To summarize, weak governance exposes military stockpiles to eager nonstate actors who sell the surplus of what they can (small arms and light weapons) where they can (often elsewhere) to whom they can (violent nonstate actors of all stripes). On average, the surge of diffusion correlates with a swell in violence at trafficking terminuses. Of course, this is one process among others that can take place amid state weakness, and only one means of weapons dispersion among others. Nonetheless, it is a likely and consequential one on the heels of dire conflict or collapse. It is also an empirically precedented one, playing out in the 1991 fall of the Soviet Union and the 2011 crumbling of Libya.

The collapse of the Soviet Union is a prime example of the dispersion consequences from a state armed to the teeth. The dismantling of Soviet arsenals sourced many illicit weapon bazaars and sprawling proliferation. Scholars emphasize that disaffected and desperate nonstate actors ransacked, trafficked, and sold billions of dollars and hundreds of thousands of tons of small arms and light weapons across the region — Abkhazia, Azerbaijan, Chechnya, Georgia, Moldova, Romania, Tajikistan, Turkey, Yugoslavia, and Ukraine. Kaliningrad in particular, geographically and politically distanced from the Soviet Union, became an immense illicit arms marketplace. Many of these locations became seedbeds of instability.

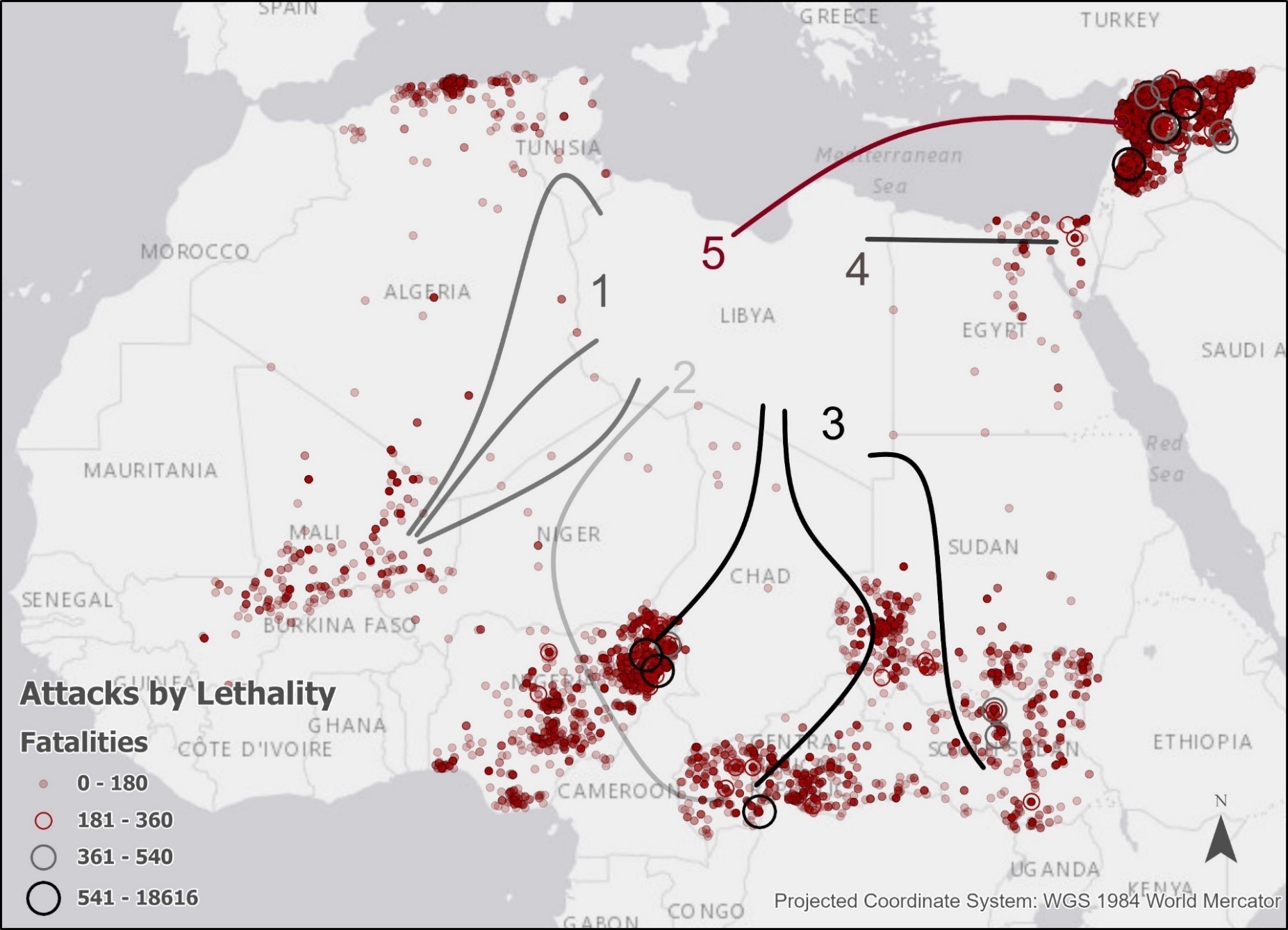

Commensurate with stockpile sizes, the breakdown of Libya followed a similar trajectory on a smaller (though still alarming) scale. In a recent study, we plot the illicit small arms and light weapons trafficking routes after Libya’s 2011 collapse. Libya had one of the largest arsenals in Africa, and its looting led to a profound episode of proliferation. Like the Soviet case, small arms and light weapons quickly crossed borders and fueled conflicts in the region.

Figure 1. Conflict events, scaled by lethality, after Libya’s collapse overlaid with illicit small arms and light weapons trafficking routes, from Oct. 20, 2011 – 2017. (Graphic by the authors)

We traced four major overland routes across 11 countries in the surrounding Sahara-Sahel and one air and maritime route into the Middle East. Violence clustered and significantly intensified at their terminuses, visible in Figure 1. In particular, newly armed Malian rebels seized several major cities and declared the Azawad independent within eight months of Libya’s collapse. Boko Haram became a key consumer of Libyan weaponry. The struggle over South Sudan escalated with the influx of weapons. Violence in the Sinai surged including the appearance of new armed groups. Libyan arms also ended up in Syria, the site of a vicious civil war.

These cases show the importance and implications of loose stockpiles. The same processes are afoot in Afghanistan and will persist. Turning to speculation, we see potential for a similar danger down the line in Ukraine, which bears some features of a weak state (especially its eastern regions). Defined as a diminished ability to exercise sovereignty in a territory, the sustained presence of Russian forces in the country and the failure to provide basic services and rule of law in areas that Ukraine still holds indicate some degree of weakness. A 2021 Small Arms Survey report determined that there were already large quantities of loose weapons and ammunition in Ukraine. Since the war began, nations have rapidly poured more basic and advanced small arms and light weapons and other weapon systems into Ukraine to reinforce fighters. Intentionally — Ukrainian resistance is a patchwork of diverse fighters — many systems are high-end yet simple to use. For example, the Javelin anti-tank missile and the Switchblade anti-tank portable drone both require less than an hour of training to use.

What will happen to all the dispensed armaments when the fighting stops? The Russo-Ukrainian War remains hot, so imagining its aftermath is more uncertain, but many might be illicitly dispersed. Whether Ukraine collapses, attains a decisive victory, or negotiates a settlement, the future of its arsenal is still worth consideration. The saturation of small arms as a national defense strategy will be difficult to undo, especially for a relatively weak state. Officials will attempt to monitor and secure the increasingly massive military arsenals. The states that sold the arms and domestic Russian and Ukrainian authorities will devote initial and primary efforts toward conventional, sophisticated platforms: aircraft, tanks, and heavy weapons, for example. In the meantime, the largest risks of proliferation lie with small arms and light weapons on hand to civilians, foreign fighters, and soldiers who might behave opportunistically as the smoke clears.

On humanitarian, geopolitical, and financial fronts, this is and should be of grave concern to states, practitioners, and scholars. As one conflict ends, the last thing stakeholders and communities need is for more to emerge in the same unstable vicinity. Thus, understanding this hydra model of war is critical to head off the diffusion of violence. This is especially true in the wake of state collapse, a rare but immense phenomenon that spills over borders more powerfully.

We offer three prescriptions to structure efforts to stem the spread of illicit small arms and light weapons during peak proliferation events. First, remember that illicit markets are regionalized. The neighboring nations that will receive the brunt of repercussions have incentives to step up to secure loose stockpiles. Other weak states have urgent reasons but weaker capacity to contain spillover, while strong states less likely to see direct negative effects ideally will contribute stockpile-security efforts in order to uphold norms and regional stability. If capacity is short or efforts are fragmented, neighbors should activate their alliance and institutional networks to help curb potential spillover. Finally, major powers with strategic or economic interests in the region might be motivated to help arrest these bursts of weapons dispersion that can have long legacies.

Second, these periods of explosive trafficking appear to be short-lived. Eventually, even vast stockpiles dry up. National dynamics shift. In Libya, local groups consolidated by 2014, leading to an increase in internal demand and consequent decrease in illicit arms outflows as territorial clashes escalated. In the loose interim, though, small arms and light weapons enabled footholds and forward movement for manifold nonstate actors. This temporal trait implies that mitigation programs should be implemented as soon as possible as stockpile insecurity mounts (insofar as shards of sovereignty allow) and certainly in the immediate aftermath of collapse or war. A boon to the domestic politics of participants, leaders can pronounce short-term commitments to high-value intervention.

Third, mediating factors determine the severity of small arms and light weapons spillover. To use an epidemiology analogy, some have greater resistance to a spreading phenomenon whether by genetics, exposure, or baseline health. Pockets of regional demand, rebel group (dis)unity, foreign fighter movements, regional capacity and coordination, the strength of interdiction techniques, the presence of external peacekeeping forces — each of these scale and structure the regional impact. These spatial traits imply that mitigation programs should be targeted based on knowledge of native inoculations along likely trafficking routes. For instance, paths to and terminuses rife with instability should be reinforced while well-governed zones can be deemphasized. Long, porous borders present a particular challenge of coverage and coordination while manageable, impassable, or intelligence-rich ones can stand alone. Stakeholders can use preexisting trafficking routes as a template, tribal travel routes and folkways as further clues, and the distribution and dynamics of regional militants as hinge points.

Altogether, given the high impact of small arms and light weapons set against scarce security resources following conflict or collapse, regional powers and their partners should amplify stockpile security in the immediate short-term in gaps of greatest weakness. This might entail targeted contingents of boots on the ground to fortify stockpiles or bombing campaigns to eradicate them. It will cost regional and global powers to safeguard insecure arsenals, but in the end it will cost far less than letting them loose to ignite violence anew.

Kerry Chávez, Ph.D., is an instructor in the political science department at Texas Tech University. Her research focusing on the domestic politics, strategies, and technologies of conflict and security has been published in the Journal of Conflict Resolution, Foreign Policy Analysis, and Defence Studies, among others. With practitioner and law enforcement experience as well as working group collaborations, she produces rigorous, engaged scholarship.

Ori Swed, Ph.D., is an assistant professor in the sociology department and director of the Peace, War, & Social Conflict Laboratory at Texas Tech University. His scholarship on nonstate actors in conflict settings and technology and society has been featured in multiple peer-reviewed journals and his own edited volume. He also gained 12 years of field experience with the Israel Defense Force as a special forces operative and reserve captain, and as a private security contractor.

Image: U.S. Navy