Join War on the Rocks and gain access to content trusted by policymakers, military leaders, and strategic thinkers worldwide.

Every year most U.S. military services struggle to reach their annual recruitment goals, but 2022 is shaping up to be one of the most challenging since the establishment of the all-volunteer force in 1973. The United States Air Force Recruiting Service faces falling short of its enlisted accessions recruiting goal for its active-duty force for the first time since 1999. There have been years since 1999 where it has been close to missing its goal, but Air Force recruiting has been proactive in identifying this year’s challenges to onboarding 26,151 new airmen. Military recruiting routinely faces challenges, but that the Air Force is struggling to meet its recruiting goal highlights the grim reality of a competitive labor market where 71 percent of Americans aged 17–24 years old are ineligible for military service. As of May 24, the Air Force had shipped 16,735 recruits off to basic military training, leaving just four months to reach its goal by Sept. 30, when the fiscal year ends. The service remains cautiously optimistic on progress toward its goal, but has indicated that it could fall 1–2 percent short. If the service does manage to reach its goal, it will likely need to exhaust its pool of qualified and waiting members of the delayed enlistment program to do so, much like the other services are indicating. This means that when the 2023 recruiting campaign begins, the concern over not meeting next year’s goal will begin even earlier than it did this year. One year of missing the goal would be manageable for the Air Force, but without additional measures it could be a more prolonged and problematic issue. Considering the ongoing challenge facing Air Force enlisted accessions, there are three areas to consider to mitigate risk: new financial incentives, an expanded recruiting office footprint, and more and better “lead sharing” with other enlisted accession recruiters.

Financial Incentives for Enlisted Accessions

The Air Force has used a variety of financial incentives to entice people into military service, but under the current circumstances it may not be enough. One popular idea is to revisit funding the Enlisted College Loan Repayment Program. Total student debt in the United States has reached $1.75 trillion, while the average amount of debt for college graduates in 2020 rose to nearly $29,000 per borrower and is expected to continue increasing. There are nearly 94 million adults in the United States with a college degree, and people who started but did not complete a degree program may have also accrued some form of student debt. The Air Force discontinued the use of the Enlisted College Loan Repayment Program in 2014, primarily due to a lack of participation. Despite a name that appears to address a serious student debt problem, the program had several constraints that made it a less desirable tool in comparison to other incentives. The program was pretty flawed, as written: It required participants to be in good standing on their loan, it could only be used for specific federal student loans, it could not be used in conjunction with another bonus, and enlistees using the program could not qualify for the GI Bill until after completing that program and completing an additional three years of service. Since the GI Bill provides more in terms of overall benefits — potentially up to $80,000 between tuition and a stipend for 36 months of school — most enlistees opted to take an initial enlistment bonus and earn their GI Bill instead of enrolling in the college loan repayment program, which has a cap of $10,000 in benefits payable over three years, following their first year of service. Unless there is a drastic change in the constraints of the program as outlined in law, renewing its funding would not be a good use of resources.

The Air Force uses bonuses as an incentive for both initial enlistment and retention focused on low manning, poor retention rates, and high replacement training costs. Typically, the more critically manned specialties have higher bonuses and volunteers for longer contracts get a larger bonus, which ensures continuity and prolongs the amount of time before a replacement must be trained. As recently as April 2022, the Air Force increased the number of career fields in which new recruits are eligible for initial entry bonuses to over a dozen. Bonuses for completing the specified training are generally $3,000 for a 4-year contract and $6,000 for a 6-year contract, but extremely hard-to-fill specialties can earn a $50,000 bonus for a 6-year contract. The Air Force has also targeted bonuses for luring new recruits with established qualifications in the cyber field, offering $12,000–$20,000 for a 6-year contract with the appropriate credentials. A new, short-term action implemented by Air Force recruiting is an $8,000 bonus for “quick-ship” recruits in cases where there is a short-notice opening for basic military training. This incentivizes an already qualified applicant and averts the loss of a training slot. The quick-ship bonuses have already been used 80 times to avert the loss of a basic military class seat valued at roughly $24,000. Though it has until now been seen as a short-term initiative, the Air Force may need to consider the quick-ship incentive for subsequent years if accessions remain below the annual goal.

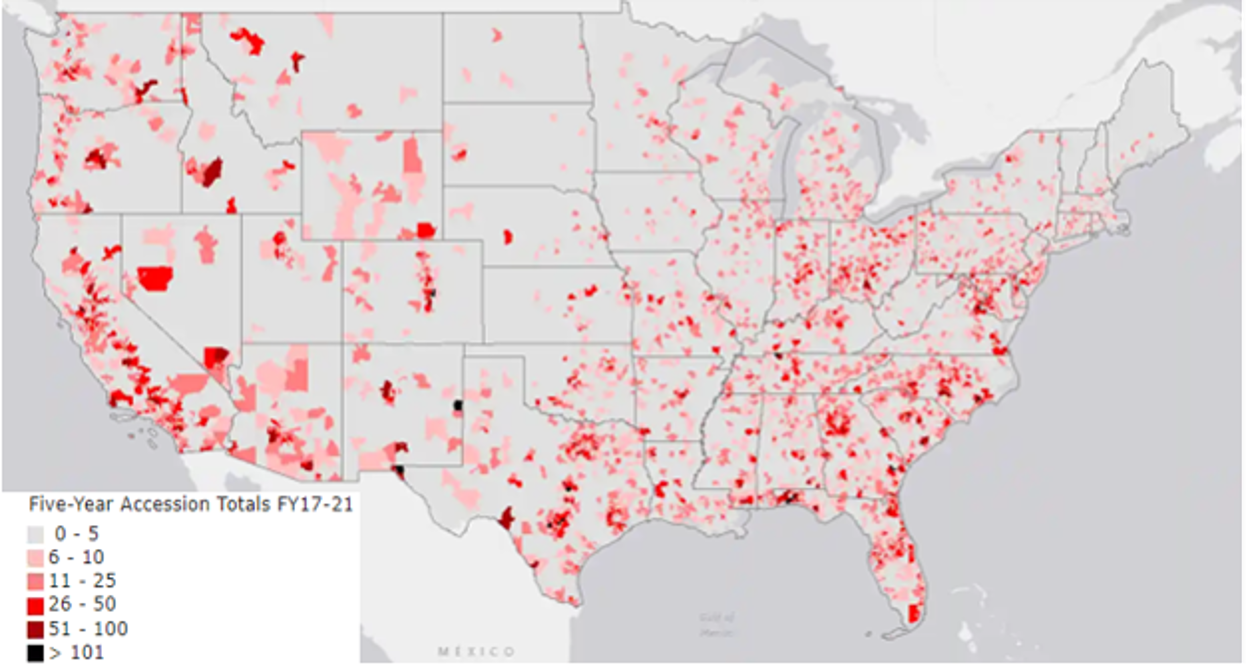

Air Force Recruiting Service enlisted accessions by zip code for fiscal years 2017–2021. (Graphic courtesy of Air Force Recruiting Service Public Affairs)

Another potential financial incentive is awarding service credit for qualified applicants with advanced experience, essentially allowing these applicants to earn a higher rank based on specific criteria. There are a few examples of this already in practice, but additional action in this area may be more compelling for recruitment. Already the Air Force allows enlistees (grade of E-1) with a significant amount of college credit to promote to E-2 (if they have 20 college credits) or E-3 (45 college credits) after completing basic military training. Other examples of this are enlistees with specific qualifications for the Air Force Band: They are eligible for higher rank at E-4. Medical officers may come in with higher rank based on their years of schooling and residency programs. The benefit of increased rank — and the increased pay that comes with it — early in a career for experience or advanced certification could improve the Air Force’s prospects for accessing the talent it needs. Specialties that might benefit from expanding this approach would be cyber career fields that have direct civilian counterparts and established certifications that the Air Force uses to develop its cyber workforce. Other possible career fields for consideration might include heating, ventilation, air conditioning and refrigeration, electricians, or even dental technicians. This approach fixes a long-standing problem of filling manning shortfalls in specific year groups. While the current approach hinges on building a replacement airman from scratch and then waiting years for them to develop, this approach allows the accession of an experienced enlistee to reach a noncommissioned officer rank in much less time. In a specialized and technical environment, individual capability can often be more important than rank, but awarding service credit may be the perfect enticement for established technicians with a desire to serve in the military without taking a drastic pay cut.

Reestablishing a Recruiting Presence

The Air Force Recruiting Service is quite aware of the impact that the pandemic has had on operations. Its commander, Maj. Gen. Edward Thomas, has stressed the need for the recruiting force to focus on a critical component of recruiting success: community engagement. During the initial onset of COVID-19, many high schools were either closed or transitioned to a virtual environment, which eliminated many traditional opportunities for recruiters to establish contact with new leads and potential applicants. After two years of pandemic operations, a sizable portion of recruiters have never conducted an in-person visit to a high school. This poses an unprecedented disruption in recruiting as recruiting assignments typically last four years. While high schools have since returned to normal operations, they may be less accommodating of campus visits due to COVID-19 concerns. The lack of contact and the regular turnover of teachers and counselors, who have considerable influence on students’ career and education plans, is forcing recruiters to allocate considerable time to rebuilding relationships with all of the schools in their area.

To better execute community engagement and empower recruiters to form strong relationships with schools, Air Force recruiting needs to evaluate its recruiting footprint. After several years of consolidating offices into hubs in some areas and decreasing the number of single recruiter offices, the service should identify ways to reverse that trend and open additional recruiting locations. The shift to centralized recruiting offices cuts office rent and logistics, but it does this at the cost of moving recruiters from the area that they service. A recruiter cannot build the same relationship with a community when they live an hour or more away. Even unofficial interactions, such as the kind that happen when a recruiter drops their kid off at school or picks up their kid from sports, is an opportunity to engage the community. The distance and time costs caused by over-centralization impact more than the recruiter: Applicants without their own transportation, or who live in a rural community with no public transport, may face significant barriers to meeting with a recruiter. Recruiters are meant to be low-density, high-demand operators. If they are too centralized, they cannot develop the community relationship effectively. Gen. Thomas has remarked on the challenge to recruiting caused by military members being disconnected from civil society. Dispersing the footprint addresses that issue.

Planning and executing an increase in the number of recruitment offices is overdue. The recruiting service was convincing in its advocacy for increasing the size of the recruiting force a few years ago and obtained funding and manpower to increase the number of recruiters in the field, but unfortunately it was not able to garner a commensurate increase in additional office space. They were able to “find” space in existing office locations to accommodate new recruiters, but many of those office solutions are suboptimal. There is an expense associated with more offices and typically office spaces are leased for long periods to lock in rents and mitigate annual cost increases. Procuring funding and coordinating space through the Army Corps of Engineers can take time, but potentially missing recruiting goals this year may provide impetus for increasing the office footprint. Additional offices could be co-located with the National Guard and reserve in alignment with direction from Air Force higher-ups to integrate their recruiting operations. At the very least, the Air Force Recruiting Service should investigate if any potential space can be found with the other services in an existing recruiting center. Even locations the Air Force recruiters vacated previously that are still under contract may be worthy of another look.

Non-Selected Commissioning Applicants as New Leads

The Air Force Recruiting Service has identified lead sharing — sharing contact information across all its recruiting elements (active duty, reserve, National Guard, Air Force Reserve Officer Training Corps, and the United States Air Force Academy) — as an important process, but because different recruiting systems have different information technology systems, they have not yet managed to refine the process. It has made strides by expanding the capabilities of its primary information system, but that system is not used by either the United States Air Force Academy or the Air Force Reserve Officer Training Corps. Lead sharing at its core is beneficial when one recruiting force finds a potential applicant that has an interest in the Air Force, but not the specific version of service the recruiter works for. In a perfect data system, the recruiter gathers information on the applicant and sends it to a more appropriate recruiter. For example, if someone may be looking to work part-time or stay close to home during their Air Force career, the lead goes to the National Guard or reserve. On the other hand, if someone is looking to go to college, that lead may get sent to the United States Air Force Academy or the Air Force Reserve Officer Training Corps for action.

The aspect of lead sharing that has the most potential but has seen the least success is the handoff of contacts from commissioning programs to enlisted accessions. Every year the Air Force Reserve Officer Training Corps and the United States Air Force Academy have many applicants for their competitive commissioning programs that are not accepted or leave the program for reasons that would not disqualify them for enlisted accessions. These applicants are valuable as leads specifically because they demonstrate awareness of the military, which increases recruiting success.

Per Air Force officer commissioning sources, each year there are roughly 10,000 people that apply to the United States Air Force Academy that are not selected. Traditionally, passing those contacts on to enlisted accessions has not been effectively executed. While some of those applicants may not be qualified or competitive enough for the commissioning programs, they may be qualified for enlisted accessions, and, equally important, they have already indicated an interest in an Air Force career. The capacity to pass those leads to the appropriate recruiters must be improved. Civilian companies often pay recruiting agencies fees of around 20 percent of a new hire’s salary to acquire talent for their business, but with the right effort the Air Force should get these leads on interested applicants at no significant additional cost. Even if current systems are not optimized to pass specific data, the data managers for both systems can gather and pass on applicant contact information in a way that could be transferred to enlisted accessions recruiters. For the Air Force’s Officer Training School, all lead information about applicants without prior service is already contained in the recruiting service’s system of record, and it should be seamlessly shared. But there is not a formalized process by which these applicants are notified of non-selection and then followed up with through a conversation on the benefits of an enlisted career. If needed, the Air Force Recruiting Service could devise specialized training to address many of the perceptions that applicants seeking a commission may have of an enlisted career. These applicants could benefit from a follow-up conversation if, for example, there were already working in temporary or short-term jobs as they finished their degrees and waited for the results of the board. Since these applicants were looking for an Air Force career anyway, this is an opportunity for an enlisted accessions recruiter to remind the applicant that an enlisted career has virtually all the benefits (health care, housing, education, insurance, paid moves, and so on) that a commission would have offered.

Conclusion

The Air Force is working in a tight labor market, just like every business currently looking for talent in the United States, and it remains successful despite these conditions. It should continue to evaluate the effectiveness of current programs and strive to develop additional ones when circumstances require. The suggested solutions above are not necessarily new and may include a cost that the Air Force has to fund in relation to its priority, but from a macro level they are relatively modest. The proposed steps are viable because they have either already been used or they are built on existing programs that can be tailored for different requirements. If the Air Force Recruiting Service acts on implementing these recommendations now, it can enhance the success of its recruiting efforts for years to come.

Kelly McElveny is an Air Force officer with 22 years of experience in areas including intelligence, recruiting, technical training, and personnel. He has supported operations in the Middle East, Europe, and Asia. The views expressed in this article do not reflect those of the Department of Defense, nor do hyperlinks constitute endorsement by the department.